Qualia

Under Qualia (singular: the Quale ., From the Latin qualis "as is") or phenomenal consciousness refers to the subjective experience level of a mental condition. Understanding the qualia is one of the central problems of the philosophy of mind . There it is assumed by some that their existence cannot be explained by means of the neurosciences and cognitive sciences .

In 1866 the American Charles S. Peirce systematically introduced the term qualia into philosophy, even if the term z. B. was mentioned about thirty years earlier by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus with reference to the philosophy of Johann Friedrich Herbart .

But it was not until 1929 that CI Lewis determined in the book Mind and the World Order the qualia in the sense of the current philosophy of mind as "recognizable characters of the given, which can be recognized and are therefore a kind of universals ". A synonym for the term qualia that is often found in literature is the English expression raw feels .

Definition

“Qualia” is understood to mean the subjective experience content of mental states. But precisely such a subjective element seems to oppose any intersubjective definition. To determine qualia, the philosopher Thomas Nagel coined the phrase that it “feels a certain way” to be in a mental state ( what is it like ). When a person freezes, for example, it usually has several consequences. For example, different neural processes take place in the person and the person will show certain behavior . But that's not all: "It also feels a certain way to the person" to be cold. However, Nagel's attempt at determination cannot be used as a general definition. A determination of qualia by the phrase “feel a certain way” presupposes that this phrase is already understood. However, if the talk of subjective experiences does not make sense, you will not understand the phrase either. Ned Block therefore commented on the problem of definition as follows:

“You ask: What is it that philosophers have called 'qualitative states'? And I answer, only half-jokingly: As Louis Armstrong said when he was asked what jazz was: If you have to ask first, you will never understand. "

The problems that arise in determining qualia have led some philosophers such as Daniel Dennett , Patricia and Paul Churchland to reject qualia as completely useless terms and instead advocate a qualia eliminativism . Ansgar Beckermann , however, comments:

“And if someone says that they still don't know what the qualitative character of a taste judgment consists of, we can counter this lack of understanding: We give them a sip of wine, then let them suck a mint and then give them another sip of the same Wein with the comment: What has changed now is the qualitative character of your taste judgment. "

The riddle of qualia

Even if the explicit discussion of qualia did not arise until the 20th century, the problem has been known for a long time: Already in René Descartes , John Locke and David Hume , similar, if not elaborated, thought processes of this kind can be found. For example, Hume claimed in his Treatise on Human Nature (1739):

"We cannot form to ourselves a just idea of the taste of a pineapple, without having actually tasted it."

"We cannot form an idea of the taste of a pineapple without actually tasting it."

Even Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz formulated the Qualia problem in a haunting thought experiment . Leibniz lets us walk through a gigantic model of the brain . Such a model will provide information on how stimuli are processed in a very complex way in the brain and ultimately lead to a reaction through the transmission of stimulus in different parts of the body (cf. stimulus-reaction model ). But, according to Leibniz, nowhere will we discover consciousness in this model. So a neuroscientific description will leave us completely in the dark about consciousness. In Leibniz's thought experiment one can easily discover the problem of quality. Because what you can't discover in the brain model obviously also includes qualia. The model may explain to us, for example, how a light wave hits the retina , thereby directing signals into the brain and ultimately processing them there. In Leibniz's view, however, it will not explain why the person perceives red. Leibniz tried to grasp the body-soul problem, which can be described in more detail with the term qualia, with the term petites perceptions .

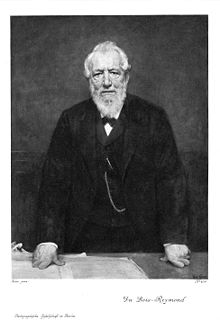

Another early formulation of the quality problem goes back to the physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond and his Ignorabimus speech . In his lecture on the limits of the knowledge of nature , given at the meeting of naturalists in Leipzig in 1872 , du Bois-Reymond explains the question of consciousness as a world puzzle :

“What conceivable connection exists between certain movements of certain atoms in my brain, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the original, indefinable, indisputable facts, 'I feel pain, feel pleasure; I taste sweets, smell the scent of roses, hear the sound of the organ, see Roth ... '"

The current debate about qualia is based primarily on the essay What is it like to be a bat? ( "How does it feel to be a bat?") Of the philosopher Thomas Nagel in October 1974. nail essay coincided with a period in which the philosophy of mind through the development of neuro- and cognitive sciences predominantly reductionist was marked. He now argues that the natural sciences cannot explain the phenomenon of experience at all. After all, the sciences are set in their method on an external perspective in which the internal perspective of experience cannot be grasped at all. Nagel tries to illustrate his position with an example that has become famous. He asks you to imagine a bat . Now, as Nagel argues, we can carry out many neuroscientific and ethological experiments with such alien creatures and find out something about the cognitive abilities of a bat. How it feels for the bat to locate an object using echolocation , for example , remains closed to us. Nagel concludes from this example that the subjective perspective of qualia cannot be inferred from the objective perspective of the natural sciences.

Qualia arguments

In addition to the generally formulated qualification problem, arguments in support of the qualia concept were repeatedly formulated. Some aim to pinpoint the problem. Others want to draw conclusions from it, such as a criticism of materialism .

The Mary Thought Experiment

The most famous qualifications-based argument against materialism comes from the Australian philosopher Frank Cameron Jackson . In his essay What Mary Didn't Know , Jackson formulated the thought experiment of the super scientist Mary. Mary is a physiologist specializing in color vision who has been trapped in a black and white laboratory since she was born and has never seen colors. She knows all the physical facts about seeing color, but she doesn't know what colors look like. Jackson's argument against materialism is now quite brief: Mary knows all the physical facts about seeing color - yet she does not know all the facts about seeing color. He concludes that there are non-physical facts and that materialism is wrong.

Various materialistic replies have been made to this argument. David Lewis argues that the first time Mary sees colors, she doesn't learn new facts. Rather, it would acquire a new skill on its own - the ability to visually distinguish colors. Michael Tye also argues that before she was freed , Mary would have known all the facts about seeing colors. Mary would just get to know a known fact in a new way. Daniel Dennett even explains that there is nothing new for Mary when she visually perceives colors for the first time. Such an extensive physiological knowledge of seeing colors - she knows everything - would give her all the information.

Missing and inverted qualia

Also with the thought experiments of the missing and inverted qualia is connected the claim to prove the puzzling nature of the qualia. These thought experiments are based on the fact that the transition from neuronal states to experiential states is by no means obvious. An example (see graphic): A neuronal state A is associated with a red perception, a state B with a blue perception. Now the thought experiment of the inverted qualia says that it is also conceivable that this happens exactly the other way around: The same neuronal state A can also be associated with a perception of blue, the same neuronal state B with a perception of red.

The thought experiment of the missing qualia also claims that it is even conceivable that a neural state is not opposed to any qualia. The idea of the missing qualia therefore amounts to the hypothesis of the “ philosophical zombies ”: It is conceivable that beings have the same neuronal states as other people and therefore do not differ from them in their behavior. Nevertheless, they had no experience with regard to the neuronal state under consideration, so the neuronal states did not correlate any qualia.

With regard to the motives for these thought experiments, one has to distinguish between two different readings - one epistemological and one metaphysical. Philosophers who prefer the epistemological interpretation want to show with the thought experiments is that Qualia not to neural states reduce leave. They argue that the imaginability of the divergence of neural state and qualia shows that we have not understood the connection between the two. The water example is often used here: if water has been successfully reduced to H 2 O, it is no longer conceivable that H 2 O is present without water being present at the same time. This is simply inconceivable because the presence of water can be derived from the presence of H 2 O under the conditions of chemistry and physics . This is the only reason why one can say that water has been reduced to H 2 O. However, an equivalent of the chemical-physical theory on which this successful reduction is based is missing in the area of neuronal and mental phenomena.

The metaphysical reading of the concepts of inverted and missing qualia, on the other hand, have even wider implications. Proponents of this line of argument want to use the thought experiments to prove that qualia are not identical with properties of neuronal states. Ultimately, you have a refutation of materialism in mind. They argue as follows: If X and Y are identical, then it is not possible for X to be present without Y being present at the same time. This can easily be illustrated with an example: If Augustus is identical with Octavian, then it is not possible that Augustus appears without Octavian, after all they are a person. Now the representatives of the metaphysical reading further argue that the thought experiments have shown, however, that it is possible that neural states occur without qualia. So qualia could not be identical to properties of neural states. Such an argument must of course accept the objection that the thought experiments do not show that it is possible for neuronal states to occur without qualia. They just show that this is conceivable . Representatives of the metaphysical reading respond that a priori imaginability always implies possibility in principle. Saul Kripke has formulated influential arguments to show this . Frank Cameron Jackson and David Chalmers offer a more recent elaboration . The so-called two-dimensional semantics are of fundamental importance here .

- Alex Byrne: Inverted Qualia. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Explanatory models

Representational strategies

Representationalist strategies enjoy great popularity among materialist philosophers, variants are represented by Thomas Metzinger , Fred Dretske and Michael Tye , for example . One goal of such positions is to reduce qualia to representational states. For example, if you prick your finger with a needle, the sting is represented by neuronal states. Experience should now be nothing other than the mode of this representation. The objection is often made that it is not plausible that representations are a sufficient condition for experience. On the one hand, simple systems such as a thermostat also have representational states; on the other hand, there also seem to be unconscious representations in humans. An example from neuropsychology are the cases of cortical blindness ( blindsight ), in which people have perceptions that they do not register cognitively or qualitatively. Some philosophers, such as David Rosenthal , therefore advocate a meta-representationalism . According to him, qualitative states are realized through representations of representations.

But now all representationalist strategies are confronted with the objection that they too cannot solve the quality problem. Because one can also ask for representational states why they should be accompanied by experience. Wouldn't all representations be conceivable without qualia?

Some materialistic philosophers react to this problem by claiming that they do not have to explain how material - for example representational - states lead to experience. For example, David Papineau has argued that one simply has to accept the identity of a state of experience with a material state without being able to demand an explanation for this identity. The question “Why are X and Y identical to each other?” Is simply a bad question and therefore the riddle of qualia turns out to be a pseudo-problem . Proponents of the thesis that qualia are puzzling reply to this objection that they would not even ask the question mentioned. They state that they would rather know how it is at all possible that the subjective experience is the same as a physical process, and they claim that this issue is not resolved, as long as no reduction of Qualia has succeeded.

While Papineau also considers the second question to be unjustified, other materialistic philosophers recognize the existence of a riddle here. Still others turn to the position of qualia eliminativism or leave the framework of materialistic theories.

Qualia eliminativism

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett makes a particularly radical suggestion for solving the qualification problem : He claims that qualia does not really exist. Such a position appears to some other philosophers as completely implausible, if not completely incomprehensible. “Of course we have subjective experiences,” they explain, “nothing could be more certain than this.” Dennett, on the other hand, claims that such utterances are only the expression of outdated metaphysical intuitions that are still fed by metaphysics in the tradition of René Descartes . In reality, "Qualia" is a completely contradictory term that could be abolished in the course of scientific progress, similar to the terms "witch" or " phlogiston ". Dennett now sets out to attack the various ideas that one has of qualia (inexpressible, private, intrinsic ), and says that these properties can in no way be attributed to qualia. According to Dennett, there remains an empty conceptual shell that can be abolished without loss. While many philosophers reject Dennett's argument, it has sparked a wide debate. Dennett's position is supported by Patricia Churchland and Paul Churchland as well as other eliminative materialists .

Non-reductionist strategies

Since reductionist and eliminative strategies face enormous problems for some, positions that explain that it is not necessary to make such attempts become attractive. The classic non-reductionist and non-eliminative position is dualism . If qualia are not material entities at all, there is no need to reduce them to neural states or to worry if such attempts at reduction fail. However, the traditional objection to a dualistic approach is that it can no longer make the interaction of Qualia with the material world understandable. After all, every physical event also has a sufficient physical cause . So there would be no room for immaterial causes. It seems to be very implausible to claim that a sensation of pain, for example, cannot be the cause of a physical event - namely the behavior of the person. The so-called Bieri trilemma offers a particularly concise formulation of these difficulties .

Another non-reductionist and non-eliminative position is conceptual pluralism , as formulated by Nelson Goodman . He claims that there are different ways of describing things that are equally important and yet cannot be traced back to one another. The pain when touching a hot stove and the neural activities in the brain of the person concerned are logically equivalent, as it were, as different sides of the same coin.

Based on panpsychism, there is an approach according to which every state of any (not necessarily biological) physical system corresponds to a torment or a set of qualia. A dualism in the sense of the “soulfulness” of things (as in classical panpsychism) does not necessarily have to be assumed. This approach has the advantage that it does not assume any qualitative “jumps” in the transition from inanimate to animate matter. Rather, the complex human consciousness is made up of “elementary aqualia” and can thus be reduced to elementary processes , analogous to the reduction of the physical appearance of humans as a many-body system to elementary physical processes. David Chalmers , for example, argues in this direction . From a scientific point of view, however, this argument is unsatisfactory, since no experiment is known with which the existence of these elementaryqualia could be proven or refuted.

Can the problem of qualia be solved?

On the part of the representatives of the Qualia concept, voices were again and again loud that the assumed “riddle” of Qualia cannot be solved. Such a position is mainly represented by philosophers who want to hold on to materialism, but consider reductionist and eliminative strategies to be implausible. For example, Thomas Nagel considers the possibility that today's science is simply not far enough to solve the quality problem. Rather, a new scientific revolution is required before an answer to this riddle can be found. The worldview before and after the Copernican change offers itself as an analogy . Some astronomical phenomena simply could not be explained in the context of the geocentric view of the world ; a fundamental change in scientific theories was necessary first. Similarly, a solution to the quality problem may only be possible through new findings or models from the neurosciences and cognitive sciences .

British philosopher Colin McGinn goes one step further. He claims that the quality problem for mankind is fundamentally insoluble. In the course of evolution, humans have developed a cognitive apparatus that is by no means suitable for solving all problems. Rather, it is plausible that basic limits are also set for human cognition and that we have reached one of these limits with the qualia. This view has in turn been heavily criticized by other philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan , who McGinn referred to as the "New Mysterian" (New Mystic ).

Further topics

- For the broader context of the qualia debates, see Philosophy of Mind , Consciousness, and Mental Causation .

- For the epistemological background of the debates about the explainability of qualia see reductionism .

- For the ontological consequences of the quality debate, see dualism and physicalism .

literature

- Ansgar Beckermann : Analytical Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind. 2nd Edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-11-017065-5 .

- Heinz-Dieter Heckmann , Sven Walter: Qualia - Selected Articles. 2nd Edition. mentis, Paderborn 2006, ISBN 3-89785-448-1 .

- Thomas Metzinger (Ed.): Awareness. Schöningh, Paderborn 1995, ISBN 3-89785-600-X .

- Jan G. Michel: The Qualitative Character of Conscious Experiences: Physicalism and Phenomenal Properties in the Analytical Philosophy of Mind. mentis, Paderborn 2011, ISBN 978-3-89785-742-1 .

- Edmond Leo Wright (Ed.): The Case for Qualia , MIT, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-262-73188-1

Trivial literature

- Norms Behr: Qualia , Amazon Createspace / Kindle Direct Publishing, ISBN 978-1534753211 : Novel about the effects of machine-triggered Qualia experiences.

Web links

- Literature on the subject of Qualia in the catalog of the German National Library

- Jay David Atlas: Qualia, Consciousness, and Memory: Dennett (2005), Rosenthal (2002), LeDoux (2002), and Libet (2004) (PDF; 197 kB)

- Peter Bieri : What makes consciousness a mystery? (rtf file; 56 kB) In: W. Singer (Ed.): Brain and consciousness. Spektrum, Heidelberg 1994, pp. 172-180

- Ned Block : several articles with an introductory and advanced character on the subject

- David Chalmers : Selected Bibliography (MindPapers)

- David Chalmers: Link Collection

- Tim Crane : The origins of qualia ( Memento from August 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), in: Tim Crane, Sarah Patterson (Ed.): The History of the Mind-Body Problem, London: Routledge 2000.

- Volker Gadenne: Three types of epiphenomenalism (PDF; 71 kB)

- Amy Kind: Qualia. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Thomas Metzinger : Presentational content (PDF; 92 kB) , in: Frank Esken, Heinz-Dieter Heckmann (Hrsg.): Consciousness and representation. Schöningh, Paderborn 1998 (Metzinger denies the existence of Qualia)

- Martine Nida-Rümelin : Qualia: The Knowledge Argument. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Carsten Siebert: The phenomenal as a problem of philosophical and empirical theories of consciousness

- Michael Tye : Qualia. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ^ Charles S. Peirce : Collected Papers . Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge [1866] 1958–1966 (reprint), § 223.

- ↑ Michael Tye: "Qualia" . In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition). Retrieved July 11, 2019

- ^ Heinrich-Moritz Chalybaeus: Historical development of speculative philosophy from Kant to Hegel. Second improved and increased edition , Leipzig / Dresden 1839, p. 69, p. 95.

- ^ Clarence Irving Lewis : Mind and the World Order. Outline of a Theory of Knowledge. Charles Scribner's sons, New York 1929, p. 121; Dover, New York 1991 (reprint). ISBN 0-486-26564-1 .

- ^ Ned Block : Troubles with Functionalism. In: Perception and Cognition. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis Minn 1978, ISBN 0-8166-0841-5 .

- ↑ Ansgar Beckermann : Analytical introduction to the philosophy of mind. 2nd Edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2001, p. 358, ISBN 3-11-017065-5 .

- ^ Emil du Bois-Reymond : About the limits of the knowledge of nature. Leipzig 1872. Reprint and a. in: Emil du Bois-Reymond: Lectures on philosophy and society. Meiner, Hamburg 1974, ISBN 3-7873-0320-0 .

- ↑ Thomas Nagel: What is it like to be a bat? ( Memento of October 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: The Philosophical Review. Cornell University, Ithaca 83/1974, pp. 435-450. ISSN 0031-8108

- ↑ Frank Cameron Jackson : What Mary didn't know . In: Journal of Philosophy. 83/1986, pp. 291-295.

- ^ Saul Kripke : Naming and Necessity . Blackwell, Oxford 1981, ISBN 0-631-12801-8 .

- ^ David Chalmers : The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1996, ISBN 0-19-511789-1 .

- ^ Thomas Metzinger : Being No One. The Self-Model Theory of Subjectivity. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass. 2003, ISBN 0-262-13417-9 .

- ^ Fred Dretske : Naturalizing the Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass 1997, ISBN 0-262-54089-4 .

- ↑ Michael Tye : Ten Problems of Consciousness. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass 1996, ISBN 0-262-20103-8 .

- ^ David Rosenthal: The Nature of Mind. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-504670-6 .

- ^ David Papineau : Mind the Gap. In: Philosophical Perspectives. Blackwell, Cambridge Mass. 12/1998, ISSN 1520-8583

- ↑ Daniel Dennett : Quining Qualia. In: AJ Marcel, Bisach: Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1993, pp. 42-77, ISBN 0-19-852237-1 .

- ↑ Colin McGinn : Problems in Philosophy. Blackwell, Oxford 1994, ISBN 1-55786-475-6 .

- ^ Owen Flanagan : The Science of the Mind , MIT Press, 1991, p. 313 .