Roman-Parthian War (58-63)

| date | A.D. 58–63 |

|---|---|

| place | Armenia |

| output | Treaty of Rhandeia |

| Territorial changes | Smaller territorial gains for the Roman client states |

| consequences | The Arsacids established themselves as Roman vassals on the Armenian throne |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Roman Empire and vassals: |

|

| Commander | |

|

Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo |

|

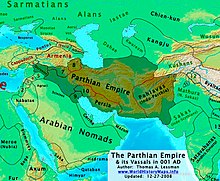

The Roman-Parthian War of 58-63 was fought between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire for control of Armenia - a buffer state between the two empires. Armenia had been a Roman client state since the days of Augustus , but in 52/53 the Parthians succeeded in bringing their own candidate, the Arsacid Trdat I (Tiridates I), to the Armenian throne. In 54, Nero became Roman Emperor and started a war. Besides the Jewish War, it was the only major military campaign during his rule.

The Romans quickly advanced under Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo , defeated Trdat's armies, and installed their own candidate, Tigranes VI. as the Armenian king. The Romans benefited from the fact that the Parthian king Vologaeses I - brother of Trdat - was apparently engaged in internal revolts. When this was over, however, the Parthians turned to the west and, after a few years of fruitless campaigns, were able to inflict a heavy defeat on the Romans in the Battle of Rhandeia.

The conflict soon ended with a compromise: An Arsakid prince ( Armenian Arsacids ) was to become the Armenian king, but had to be approved by the Romans beforehand. Nero staged this in front of the Roman public as a great victory. This war was the first direct military conflict between Rome and the Parthians since Crassus' defeat at Carrhae and Mark Antony's wars against the Parthians a century earlier. It was to be the first in a series of further wars between the two powers for supremacy over Armenia ( Roman-Persian Wars ).

background

Rome and the Parthians came under attack in the 1st century BC. Because of the predominance over the Caucasus area to each other. Various empires and countries were located in this area, the largest of which was the Kingdom of Armenia . For the Parthians in particular, the control of this region was of great strategic importance. Augustus managed to take advantage of internal Armenian conflicts and with the coronation of King Tigranes III. in the year 20 BC To bind Armenia to Rome. The Roman influence lasted until AD 37 when Orod became the new king of Armenia. His brother Mithradates was brought back to the throne with the help of the Romans 42. However, this was deposed by his nephew Rhadamistos 51. But Rhadamistos was unpopular with large parts of the Armenian nobility, so that the Parthian king Vologaeses I saw an opportunity to intervene. His troops quickly conquered the royal cities of Artaxata and Tigranokerta and put his own brother Trdat I on the throne. Due to a harsh winter and an epidemic, the Parthian troops had to withdraw, which Rhadamistos took advantage of to bring the country back under his control. But now the nobility rebelled against him, and Rhadamistos had to flee to Iberia , so that Trdat I became king again.

In the same year Emperor Claudius died in Rome and his young stepson Nero followed him. The growing influence of the Parthians in an empire viewed as a Roman area of interest worried and provoked the Roman leadership. This conflict was immediately considered a test for the new emperor. Nero saw an opportunity to distinguish himself; he reacted energetically and sent the general Corbulo, who had distinguished himself in Germania and was currently in the province of Asia , with an army against Armenia.

Diplomatic maneuvers and preparations

Corbulo was given the governorship of the two Roman provinces of Cappadocia and Galatia . First he was a propaetor , then a proconsul ( empire ). Although Corbulo had soldiers on site, he was still in command of Roman legions stationed in the province of Syria .

Initially, according to Tacitus , the Romans wanted to resolve the crisis diplomatically despite the military build-up, and they sent embassies to Vologaeses. But this was busy with an uprising, so that he had to withdraw his troops from Armenia. Corbulo saw the opportunity for military action and used the time to discipline his troops and prepare them for battle. According to Tacitus, Corbulo released all old and sick soldiers and accustomed his troops to the harsh Anatolian winter by having them camped in tents. Deserters were executed. He himself was regularly among his soldiers.

Now the Romans set increasingly unacceptable conditions and so Trdat refused to travel to Rome covered by his brother, as Nero demanded, and instead advanced against Armenians loyal to Rome. Tensions increased, so that in the spring of 58 war broke out.

Outbreak of war and Roman offensive

Corbulo stationed his troops in several camps near the Armenian border. Paccius Orfitus - a former Primus Pilus - undertook a raid against Armenia against Corbulos's orders. He met the Armenians unprepared, but was defeated. The fleeing Romans caused panic among the other border troops. Corbulo severely punished the survivors and their commanders.

Despite this incident, Corbulo was well prepared. He had trained his army for two years and was in command of three legions ( Legio III Gallica , Legio IIII Scythica , Legio VI Ferrata ). In addition, there were auxiliary forces ( auxiliary troops ) and troops Roman vassal: Aristobulos from Lesser Armenia and Polemon II. From Pontos . It was advantageous that Vologaeses was busy with internal rebellions again. At the Caspian Sea the Hyrcans had risen and the Dahae and Saks from Central Asia invaded the empire. Vologaeses could not support his brother.

The fighting took place along the border. Corbulo protected places loyal to Rome and attacked localities loyal to the party. Trdat avoided a major battle, so Corbulo split his troops to attack multiple locations at the same time. He also called on the kings Antiochus IV of Commagene and Parsman I of Iberia to attack. In addition, he went into an alliance with the tribe of Moshi one in eastern Anatolia.

In the end, both sides agreed to meet. Trdat went to the meeting point with a thousand riders, while Corbulo brought up the entire Legio VI Ferrata as well as 3000 Legio III Gallica and auxiliary troops in full riot gear for the exhibition. Seeing this, Trdat doubted the Romans' intention and did not approach. During the night he withdrew. Trdat now tried to interrupt the Roman supply routes that led from Trebizond on the Black Sea coast over the mountains to Armenia. But this failed because the Romans had built fortifications along the roads.

Artaxatas case

Corbulo decided to attack the most important positions of the Armenians. These not only controlled the surrounding area, but would eventually force Trdat into an open field battle to defend them. Corbulo successfully stormed three castles, including Volandum (possibly today's Iğdır ). He suffered few losses while the castles' crews were being massacred. Terrified by these successes, some towns and villages surrendered. The Romans were preparing to attack the capital of northern Armenia, Artaxata . Trdat went towards the Romans. The attackers, reinforced by a division ( vexillation ) of the Legio X Fretensis , marched in a square , accompanied by horsemen and archers. Trdat could not stop the advance by his attacks and feinting ( Parthian maneuvers ) and decided to give up Artaxata. The townspeople surrendered to the Romans and were spared, while Artaxata was burned down because the Romans were unable to deploy occupying forces.

Tigranokerta's case

In 59 the Romans marched south towards the second Armenian capital Tigranokerta (poor. Tigranakert). Along the way, those who resisted were defeated and those who surrendered spared. In the dry and harsh climate of northern Mesopotamia, the soldiers suffered hunger and thirst until they reached the fertile areas of Tigranokerta. Meanwhile, a plot of murder against Corbulo was uncovered and some Armenian nobles who were on the Roman side were accused and executed. According to Sextus Iulius Frontinus , the Romans shot the head of one of the conspirators over the city wall. The head happened to end up where the city council met. Startled by this, they decided to hand over the city. An attempt by Vologaese to get to Armenia was repulsed by the Roman auxiliaries under Verulanus Severus.

The Romans now controlled all of Armenia and installed the Herodian Tigranes VI, the last descendant of the royal dynasty of Cappadocia , as the new king in Tigranokerta. Some tracts of land in western Armenia were given to Roman vassals. Corbulo withdrew with his army to Syria, but left 1000 legionaries, three auxiliary cohorts and two Alen cavalry to the new king . Corbulo was named governor of the province of Syria for his success.

Parthian counterattack

The Romans knew that the peace was fragile and that the Parthian king would turn to Armenia as soon as the internal uprisings were resolved. Although Vologaeses did not want to risk an open conflict yet, he had to intervene in 61 because Tigranes IV had attacked the northern Parthian province of Adiabene . The governor Adiabenes Monobazus II asked for help from the king, whose reputation also depended on this crisis. Vologaeses reached an agreement with the rebellious Hyrcans and called a meeting. This particular Trdat as the Armenian king, who was then crowned with a diadem during the meeting. To bring him back to the throne, Vologaeses assembled cavalry units under the command of Monaeses and infantrymen from Adiabene. Meanwhile, Corbulo sent the Legio IIII Scythica and the Legio XII Fulminata to Armenia, while he commissioned the Legio III Gallica, Legio VI Ferrata and Legio XV Apollinaris to strengthen the fortresses on the Euphrates - the Roman-Parthian border - to prevent an invasion. He also asked Nero to designate a new legatus for Cappadocia .

Parthian siege of Tigranokertas

Monaeses moved across the border towards Tigranokerta. But Tigranes IV had prepared the city for a siege. The Parthians could not take the city and withdrew. Corbulo sent an embassy to Vologaeses, who had set up camp in the border town of Nisibis . The defeat at Tigranokerta and a lack of provisions caused Vologaeses to withdraw his troops from Armenia. But the Romans also withdrew from the country. A ceasefire was reached and a Parthian delegation made its way to Rome. But the negotiations failed and in the spring of 62 the war broke out again.

In the meantime, the new legatus named Lucius Junius Caesennius Paetus reached Cappadocia. The Roman army was divided between Paetus and Corbulo: Corbulo retained the III Gallica, VI Ferrata and X Fretensis legions, while Paetus received command of the IIII Scythica, XII Fulminata and the newly arrived Legio V Macedonica . He also had the auxiliaries from Pontus, Galatia and Cappadocia under him. But the relationship between the two commanders was strained. It is worth noting that Corbulo kept the most experienced legions for himself and gave the rest to Paetus, although he would bear the brunt of the fighting against the Parthians. A total of six legions, which already accounted for 30,000 men, faced the Parthians. The exact number of auxiliary troops is not known, but seven ales and cohorts were stationed in Syria alone, representing 7,000–9,000 men.

Battle of Rhandeia

Paetus was confident of victory and returned the Parthian declaration of war. He marched on the Parthian-occupied Tigranokerta, while Corbulo stayed in Syria and further strengthened the fortifications on the border. Paetus only had the two legions IV Scythica and XII Fulminata with him. He conquered a few smaller forts, but had to withdraw in winter due to a lack of provisions.

Originally the Parthians wanted to attack Syria, but were then deterred by Corbulo's measures and demonstrations of force. He had the Euphrates monitored by a flotilla and even built a bridge over the river to send armies over if necessary. Therefore, the Parthians turned to Armenia. Paetus had dispersed his troops there and did not notice the advance of the Parthians. When he found out about it, he wanted to go against Vologaeses, but when his reconnaissance party was defeated he panicked. Paetus sent his family to Arsamosata to safety and wanted to hinder the Parthian advance by occupying the mountain passes in the Taurus Mountains . But this only made his armies more scattered and were defeated one by one by the Parthians. Morale sank and panic spread. The retreating Romans gathered at Rhandeia on the Arsanias and built a fort there. The Parthians took this opportunity and besieged the Romans. In his distressed situation, Paetus hastily sent a message to Corbulo, who was supposed to save him.

When the cry for help reached him, Corbulo set off with half of his men. On the way he gathered up Paetu's scattered men. But before Corbulo reached Rhandeia, Paetus had already surrendered: The Parthians were aware of the advancing army and pressed the Romans more and more until Paetus wrote to Vologaeses to ask for negotiations. Conditions for the Romans were humiliating. Not only should the Romans leave Armenia and hand over all fortifications, they should also build a bridge over the Arsanias River, over which Vologaeses could then triumphantly move in, sitting on an elephant. In addition, the soldiers were robbed and - what was worse - the Romans had to crawl under a yoke as a sign of total humiliation. When the two Roman groups met at Melitene's , scenes of great sadness took place. While Corbulo regretted the loss of his successes in previous years, Paetus tried to persuade him to attack Armenia. Corbulo turned him down because he did not have the authority to make such a decision and because the army in this condition was unable to campaign. In the end Paetus withdrew to Cappadocia and Corbulo to Syria, where he received a Parthian embassy. Corbulo was supposed to demolish the bridge over the Euphrates, while Corbulo wanted the Parthians from Armenia. Both reached an agreement and withdrew their troops, and Armenia was in fact left under Parthian control until the situation could be resolved through negotiations in Rome.

Corbulo's return and the peace agreement

Rome seemed to know nothing of the situation in the east and, according to Tacitus, the Senate had triumphal arches built on the Capitol for victory, although the war was not over yet. But the illusion was shattered with the arrival of the Parthian delegation, and after questioning the centurions who had accompanied the delegation, the true extent of the disaster that had been caused by Paetus was revealed to Nero. Even so, the Romans would rather risk a dangerous war than accept a dishonorable peace. Paetus was ordered back and Corbulo reinstated in his offices and elevated above all governors and vassal kings. Corbulo's post in Syria was given to Gaius Cestius Gallus .

Corbulo reorganized the army and transferred the demoralized Legions IV Scythica and XII Fulminata to Syria, left the Legio X Fretensis as protection for Cappadocia and led his veterans of the Legions III Gallica and VI Ferrata to Melitene, where he assembled the invading army. In addition there were the Legio V Macedonica, which had not participated in the war and was stationed in Pontos, and the newly arrived Legio XV Apollinaris, a large number of auxiliary troops and contingents of the vassal kings.

After his army had crossed the Euphrates, following a route that Lucius Licinius Lucullus had opened a century earlier, he received embassies from Trdat and Vologaeses. Given the large army and capabilities of Corbulos, the two Arsacids decided to negotiate. Corbulo made Nero's position clear: if Trdat accepted his crown from Rome, there would be no new war. Trdat agreed to negotiations and they met at Rhandeia, the site of the Roman defeat a year earlier. For the Armenians, the place was a proof of their strength, while Corbulo wanted to wipe out the shame with a treaty in the spirit of Rome. On site, Corbulo Paetu's son had the bones of the fallen Roman soldiers collected and buried appropriately. On the day of the trial, the sides met with twenty riders each between the camps. Trdat agreed to go to Rome and receive the crown through Nero. As a token of his approval, Trdat arrived in parade uniform a few days later in the Roman camp and laid his crown as a sign of submission at the feet of a statue of Nero.

aftermath

In 66 Trdat visited Rome to receive his crown and was lavishly received by Nero, who took the opportunity to increase his own popularity. Nero ordered the gates of the Temple of Jan to be closed, which was only possible in times of peace throughout the empire.

Nero celebrated this peace as a great success: he was celebrated as emperor and held a triumphal procession , although no new country had been conquered and the peace was more a compromise than a clear victory. Because although Rome was able to assert itself militarily in Armenia, they lost on the political level. They had no real alternative to the Armenian throne other than the Arsacids. In nominal terms, Armenia would be subject to Rome, but in real terms would increasingly come under Parthian influence. In the judgment of later generations, Nero had lost Armenia, and although the Peace of Rhandeia ushered in a period of relatively peaceful relations for the next 50 years, Armenia continued to be a bone of contention between Rome and the Parthians. This peace was kept for a short time, even when the majority of the Roman Eastern armies were busy suppressing the Jewish War.

Corbulo was also celebrated, but his popularity with the people and the army made Corbulo a potential rival of Nero. When the Vinicianian conspiracy against Nero was exposed, at the center of which was Corbulo's son-in-law Annius Vinicianus, Nero's suspicions were confirmed. While Corbulo 67 was traveling in Greece, Nero demanded his death. When Corbulo found out about this, he committed suicide.

The inconclusive Roman-Parthian War also made it clear to the Romans that their defensive system in the east, which had been built up by Augustus, was no longer adequate. A restructuring of the eastern areas followed: the client states Pontus and Colchis (in 64) and Cilicia , Commagene and Lesser Armenia (72) were converted into Roman provinces. The number of local legions was increased and the Roman presence in the vassal states of Iberia and Albania in the Caucasus increased in order to encircle Armenia. Direct Roman control was extended along the entire Euphrates, which marked the cornerstone for the eastern Limes that would last until the Muslim conquests in the 7th century.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Bivar (1968), p. 85.

- ↑ a b Bivar (1968), p. 80.

- ↑ Bivar (1968), p. 76.

- ↑ a b Bivar (1968), p. 79.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XII.50-51

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.6

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.7-8

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 309

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.8

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.9

- ↑ Bivar (1968), p. 81

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 311.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.35

- ↑ a b c Tacitus, Annales XIII.37

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XIII.36

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 312.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.38

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XIII.39

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 314.

- ^ Southern (2007), p. 301.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.40

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIII.41

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIV.23

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XIV.24

- ↑ Frontinus , Strategemata , II.9.5

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XIV.26

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.1

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.2

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), pp. 318-319.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.4

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.5

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XV.7

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.6

- ↑ Goldsworthy (2007), p. 320

- ↑ Sartre (2005), p. 61.

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XV.8

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XV.9

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.10

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.11

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.12

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.13-14

- ^ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana LXII.21

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.14-15

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.16

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XV.17

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.18

- ↑ a b Tacitus, Annales XV.25

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.26

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.27

- ^ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana LXII.22

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.28

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales XV.29

- ↑ Shotter (2005), p. 39.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana LXII.23.4

- ↑ Wheeler (2007), p. 242.

- ↑ Festus , Breviarium XX.1

- ↑ Farrokh (2007), p. 150

- ↑ Shotter (2005), pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Shotter (2005), pp. 69-70.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Historia Romana LXIII.17.5-6

- ↑ Shotter (2005), p. 72.

- ↑ Wheeler (2007), p. 243.

swell

-

Tacitus , Annales . Translation based on Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (1876) .

Tacitus , Annales . Translation based on Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (1876) . - Cassius Dio , Historia Romana . Loeb Classical Library edition (1925)

literature

- HDH Bivar: The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids: Continuation of conflict with Rome over Armenia . In: William Bayne Fisher, Ilya Gershevitch, Ehsan Yarshater, RN Frye, JA Boyle, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, Charles Melville (eds.): The Cambridge History of Iran . Cambridge University Press, 1968, ISBN 0-521-20092-X .

- Kaveh Farrokh: Parthia from Mark Antony to the Alan Invasions . In: Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War . Osprey Publishing, 2007, ISBN 1-84603-108-7 .

- Adrian Goldsworthy: Imperial legate: Corbulo and Armenia . In: In the name of Rome: The men who won the Roman Empire . Phoenix, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7538-1789-6 .

- Maurice Sartre, translated by: Porter, Catherine & Rawlings, Elizabeth: The Middle East Under Rome . Harvard University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-674-01683-5 .

- David Shotter: Nero - Second Edition . Routledge, 2005, ISBN 978-0415319416 .

- Pat Southern: The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History . Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-532878-3 .

- Everett L. Wheeler: The Army and the Limes in the East . In: Gardiner, Robert (Ed.): A Companion to the Roman Army . Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2007, ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8 .