Richard Mather

This wood engraving by John Foster is dated around 1670 and is the oldest known portrait printed in North America. Possibly it was intended as a frontispiece for Increase Mathers The Life and Death of that Reverend Man of God, Mr. Richard Mather . 5 copies have been preserved, one each from the American Antiquarian Society , the Massachusetts Historical Society , Princeton University , Harvard University , and the University of Virginia .

Richard Mather (* 1596 in Lowton , Lancashire ; † April 22, 1669 in Dorchester , Massachusetts ) was an English clergyman who, after emigrating in 1635, became one of the most important spiritual leaders of the first generation of Puritans in New England . As a long-time pastor of Dorchester, he was instrumental in shaping the history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony .

Live and act

England

Richard Mather was born in Lowton, a village near Manchester , in 1596 , the son of Thomas Mather and his wife Margrett (née Abrams) into a family of coat-of-arms farmers . At the school of Winwick he learned Latin as well as Greek and proved to be such a good student that at the age of only fifteen, on the recommendation of his schoolmaster, he himself took a job as a teacher in the newly founded school of Toxteth Park (now a district of Liverpool ) found. In Toxteth, Mather was deeply impressed by the piety of his Puritan tenant Edward Aspinwall and in 1614 he experienced his own conversion experience , which made him a supporter of the Puritan reform movement.

He enrolled himself in 1617 at Brasenose College of Oxford University , but the university environment was repulsed by the profane life world. After he had only studied for a few months, he received a call from the parish of Toxteth, which had chosen him as the successor to their pastor, who had since died. After a period of reflection, Mather accepted the request and returned to his teaching post in Toxteth. He delivered his first sermon in November of that year as a dedication to the recently completed new church in the town. The parish election by the parish is a clear indication that the parish itself largely attributed Puritan teachings. The official ordination of Mathers was performed shortly thereafter in the presence of Thomas Morton , Bishop of Chester. In the following years Mather worked in the priesthood, as it seemed right to him by virtue of his Puritan convictions, and thus violated the prescribed Anglican liturgy in some points . The first few years of his work went very smoothly. When he asked for the hand of Katherine Holt in 1624, her father initially refused to approve of Mather's non-conformist sentiments, but then finally gave in, possibly because the love affair had led to a premarital pregnancy: barely seven and a half months after the wedding, the first was already Son of the couple, Samuel Mather , was born. Mather presumably continued to work as a teacher until 1624; Jeremiah Horrocks , who was born in Toxteth in 1619 and who would later become famous as an astronomer , may have been among his students .

The conflict between the Puritans and the Anglican State Church escalated after the coronation of Charles I , who with loyal clergymen such as Richard Neile , ordained Archbishop of York in 1631 , and William Laud , from 1633 Archbishop of Canterbury , did a far-reaching purge of the Church of no compliant priests made an effort. Mather was also reviewed and removed from office in August 1633 by a commission from the Bishop of Chester. Influential friends of Mathers were able to obtain a revocation of the judgment in November of that year. In December of that year he had to face another interrogation, this time by an archiepiscopal commission from York. In response to his testimony that in fifteen years as pastor he had never worn the choir shirt prescribed as a liturgical robe , one of the commissioners is said to have exclaimed that it would have been better for Mather if he had fathered seven bastards instead . Mather was again suspended.

Emigration to New England

Like thousands of other Puritans of the 1630s, Mather joined the " Great Migration " and in 1635 emigrated with his family to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1628 . He recorded the pros and cons of his decision in a minute argument (The Removing from Old England to New) . On the one hand, there were fundamental considerations that led to his decision - the impossibility of realizing a puritanic church leadership in England even at the parish level and the associated risk of negligently endangering the "purity" of the church - on the other hand, an end- time expectation typical of the time , especially the concern that England would soon be punished by the wrath of God. Following Spr 22.3 EU, he concluded that it would be wiser to evade the expected wildfire by emigrating. Last but not least, his lines speak of the sheer fear of torture. He was encouraged in his decision by letters that the Puritans John Cotton and Thomas Hooker , who had already emigrated to Massachusetts, had sent to their fellow believers, of which numerous handwritten copies were circulating.

On the day of his departure, Mather began to keep a diary . It is a revealing testimony to the living conditions on board an Atlantic sailor - in particular the oppressive boredom that spread among the 100 or so emigrants after a while - and in one episode it also records the amazement of the passengers when their ship left a school of dolphins was accompanied, as was the good mood (a marvelous merry sport) that arose when one of these animals was caught and eviscerated on board - the sight reminded the passengers of the slaughter of a pig and thus of their usual country life. After many uneventful weeks, the ship, anchored off the coast of Maine, was hit by a violent storm on August 15, but after two days and many prayers it still reached the port of Boston unscathed .

Initially, Mather had some problems coming to terms with the congregationalism practiced in Massachusetts . Especially at the instigation of John Cotton, the restrictions on parish membership had recently been tightened considerably. According to the Congregational parish constitution of a new community sufficiently "visible saints" had to establishing (visible saints) come together to covenant with one another and with Christ. The Puritans of Massachusetts believed that God's “ secret advice ”, that is, his decision about a person's salvation or damnation, was already on earth, if not ultimately valid, at least with some probability. As visible saints can credibly were Christians who had at a public hearing by an account of her conversion experience that they not only righteous, but seems to be in the grace were. When Mather applied for admission to the Boston parish shortly after his arrival and faced interrogation, he was initially refused membership to his surprise - the stumbling block was his official church ordination or Mather's belief that this was already sufficient to also be in Massachusetts to be able to work for and in the English Church. It was only after he had distanced himself from his previous views in a letter of justification (Some Objections Against Imposition in Ordination) about the symbolic content of the laying on of hands in the ordination mass that he was found with reasonable probability blessed and accepted into the Boston congregation.

Soon after his arrival, several settlements in the colony advertised that Mather could be their pastor. He finally chose Dorchester south of Boston, where the settlers awarded him more than 100 acres of land. Dorchester had been nearly depopulated shortly before when much of the local parish had migrated to Connecticut following Thomas Hooker . The overly strict admission criteria were the reason the original ward moved to Connecticut, and it also made the preparatory hearings for a new ward more difficult. By March, Cotton's proposals for the local government became law; the general court of the colony now demanded that a congregation could only be founded with the placet of the magistrates and the clergy of the neighboring towns. When the settlers of Dorchester underwent the prescribed test of faith on April 20, 1636, a large number of them could not believe that they were actually converted and in grace. Only after Mather had trained his flocks for months in the principles of Reformed theology could enough saints be found for the foundation of the church when the procedure was repeated in August that year , and Mather took up his office as head of the church.

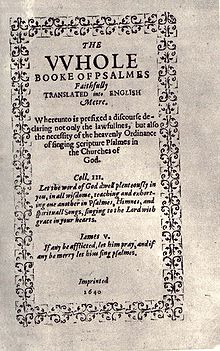

Unlike John Cotton and Thomas Hooker, Mather was not an innovative theologian and was not a prominent player in the scholarly controversy over the opinion leadership of the Puritan movement in motherland England, but he was highly regarded in Massachusetts and was often entrusted with tasks that were not just Dorchester, but affected all of Massachusetts. In 1640 he contributed to the new translation of the psalter in the Bay Psalm Book , which was the first book printed in New England in 1640 and was henceforth used in all New England churches. Many researchers also attribute the anonymous foreword to Mather. In 1643 he was given the honor of preaching in Boston for the annual governor election.

Positions on the municipal constitution

Questions such as the one debated about church planting were central points of contention in the Puritan movement and also and especially preoccupied the New England congregationalists, since they had the opportunity, far from official church reprisals, to put their ideas of a church constitution into practice. Although Mather initially struggled to come to terms with the Cotton-shaped community constitution, he soon became one of the most prominent advocates of congregational ecclesiology himself. This is evidenced by a letter he wrote in 1636 to a cleric in Lancashire, known only by the initials EB, who had previously turned to Mather with a request for an explanation of the new parish constitution in Massachusetts. In many theological debates - which had immediate social effects in Massachusetts - Mather subsequently took an intermediary role and was able to bridge differences of opinion between different congregations, but also between the lay brothers of his own congregation. He spoke out against a relaxation of the conditions for admission to the church - that is, he preferred to accept that a righteous person would be denied entry to the church than to allow a possible hypocrite to be admitted - but on the other hand he also advocated infant baptism the offspring of unconverted Christians.

Mather defended the congregational experiment, the New England Way , also against critical voices from the mother country, who sensed the danger of heresy and anarchic conditions in the realized community autonomy. Conversely, the Massachusetts Congregationalists hoped to be a role model for the motherland - in the famous words of John Winthrop a “ city on the hill ” visible from afar - and tried to influence the development of the Puritan movement in England by publishing their writings to take. This need became particularly urgent to them after the Scottish army had emerged victorious from the war against the royal English troops in 1640 and under these circumstances more and more English Puritans embraced Presbyterian principles based on the Scottish model.

Mather's contribution to this debate was a series of tracts that he sent to London for publication after the outbreak of the English Civil War . However, they hardly had the hoped-for effect, only one, An Apologie of The Churches in New England for Church Covenant (1643, probably written as early as 1639), was printed. The clerics of the colony ultimately designated John Cotton, whose Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven were presented in 1644, as the author of the quasi-official principles of the New England municipal constitution . Mathers Reply to Mr. Rutherford was directed against the Scotsman Samuel Rutherford , who had published an ambitious codification of the principles of Presbyterianism with Due Right of Presbyteries in 1644 , but to answer this challenge, the superiors of the colony already had Thomas Hooker to write an officious one Replica determined, his Survey of the Sum of Church Discipline appeared in 1648. Mather wrote A Modest and Brotherly Answer to Mr. Charles Herle around 1646, together with William Tompson, the pastor of Braintree, as a replica of a volume by the Presbyterian Charles Herle. But since Herle himself was of more epigonal importance and his work had already received little attention in England, the busy Puritan printers saw no need to print the replica on it. The only noteworthy response that Mather experienced in England was a polemic by the English Presbyterian William Rathbond - also a marginal figure in theological discourse - against the New Englanders, who apparently referred to Mathers' letter to the unspecified, which he had written eight years earlier EB related. The challenged Mather began to write an ambitious reply, but shortly before he wanted to send the 600 manuscript pages to the printer, Rathbond died, so that a continuation of the pen war was unnecessary.

In these writings, Mather indulged in a lively rhetoric, peppered with satirical side comments and undisguised abuse, which represents a noticeable break with the formal conventions of scholarly disputation that had shaped the theological literature of New England until then. His biographer BR Burg even sees the style of the political debates of the American Revolution as modeled in this prose . The sermons received in front of his congregation in Dorchester are shaped by a different style: unlike the baroque prose of his English contemporaries (such as John Donnes ), they can stand as a prime example of the unadorned, but straightforward plain style that represented the stylistic ideal of the Puritans of New England.

The Synod of 1646–1648

The fact that Mather was soon to be one of the most influential clergy in Massachusetts was shown at the first synod of the New England congregations in 1646, at which the religious practices of the colonies of Massachusetts and Connecticut were to be codified uniformly and bindingly and then submitted to the General Court for ratification. As a basis for work, two pastors submitted their drafts, one Ralph Partridge, the other Richard Mather. The text finally adopted after two years of deliberation in 1648 as A Platform of Church Discipline Gathered Out of the Word of God was based for the most part on Mather's suggestion, even if he was only concerned with one of the two most contentious questions - the relationship between the spiritual and the secular Regiment on the one hand, after admission to the baptism of children on the other - could prevail. On the previously controversial issue of parish membership, however, there was agreement that the rules introduced by John Cotton and defended so verbatim by the Mather would stand. The code, commonly known as the Cambridge Platform , represented a kind of constitution for the congregational community in New England for many decades and is considered the most important document in American church history in the 17th century.

The relationship between spiritual and secular power - in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the pastors and parishes to the magistrates and the General Court of the colony - was particularly urgent to Mather, since after 1635 the churches of the colony became increasingly dependent on the executive organs of the Colony, but such an Erastianism could hardly be reconciled with the demand for community autonomy so vehemently defended by Mather. He had already seen the General Court's mere demand to convene a synod not only as a presumption of office, but also feared that such influence would ultimately lead to the establishment of a de facto Presbyterian system. Even if Mather's sharpest points against the magistrates were toned down or shortened, the final version of the Cambridge Platform clearly bore his signature on this point, expressly guarding against any interference by the magistrates in community affairs.

On the other hand, Mather was initially unable to prevail with his views on infant baptism. This sacrament was and remained for the children of converted Christians, that is, the “full-fledged” parishioners who were entitled to partake of the Lord's Supper, while it was withheld from the children of baptized but unconverted parents. Mather took up this topic again and again in his sermons in the years after the synod and advocated a relaxation of the regulations, but was also unable to convince his own congregation in Dorchester.

The Half-Way Covenant

In a further synod in 1662, the Cambridge Platform underwent a decisive modification on the still controversial question of infant baptism, which is generally considered to be the turning point in the history of New England Puritanism. The restrictive provisions of the parish constitution meant that fewer and fewer of those born afterwards were entitled to participate in the sacraments. The children of the first generation of settlers were now reaching adulthood, but few took the parishes' entrance examination, and many were excluded from the sacrament. When this second, mostly unconverted generation had offspring, they were also denied the sacrament of baptism. It became apparent that the continued existence of the Cambridge Platform would lead to the fact that, in the long term, the unbaptized would make up the majority of the population in New England. The status quo also harbored some social explosives, as more and more unconverted people saw themselves excluded from the social prestige associated with parish membership and so dissatisfaction with the conceit of the saints spread.

Particularly after the Stuart Restoration in the mother country, it soon seemed necessary to consolidate the cohesion of the colony through a stronger involvement of the unconverted. In a synod that met in Boston in March 1662, Mather was again one of the opinion leaders of the faction who advocated an increase in the baptismal donation, but not only saw resistance from influential preachers such as John Davenport and Charles Chauncy , President of Harvard College , exposed, but also that of his own two sons, Eleazar and Increase. After a heated debate, in the so-called Half-Way Covenant, he pushed through that children and grandchildren of unconverted Christians should also be baptized. Christians who wanted to join the church but did not meet the admission requirements were granted "half" membership, which allowed them to partake of the sacrament but denied them the right to vote on church matters.

Mather's success in the dispute over the Half-Way Covenant was diminished by the fact that his own community in Dorchester refused to accept the resolution and only implemented it after Mather's death under his successor Josiah Flint. Mather presided over the Dorchester Congregation until his death; on April 22, 1669 he succumbed to renal colic .

progeny

Mather's marriage to Katherine Holt had six sons, one of whom died as an infant. Of the remaining five, three were born in England: Samuel, Timothy and Nathaniel Mather, the two youngest, Eleazar and Increase Mather, on American soil. Samuel Mather was the only one of the Mathers who immigrated permanently to England in 1650, where he became famous as a preacher and later as the author of a systematic treatise on typological Bible exegesis .

After the death of his first wife in 1655, Richard Mather married Sarah Cotton, John Cotton's widow, on August 26, 1656, bringing together two of New England's most influential families under one roof. His fifth son from his first marriage, Increase Mather , consolidated this union when he married Maria Cotton, the first daughter of John Cotton from his marriage to Sarah Cotton, Increases stepmother, in 1662. Increases and Mary's son, Cotton Mather , bore the names of his two famous grandfathers and in turn became the leading thinker of the third generation of Puritans in Massachusetts.

Both Increase and Cotton Mather each wrote a biography about Richard Mather. Increase Mather's The Life and Death of That Reverend Man of God, Mr. Richard Mather , initially appeared anonymously in print in 1670 and is one of the first biographies written on American soil . If the work also contains a wealth of “mundane” biographical details, so Like other Puritan biographies, it is primarily conceived as edification literature and stylizes Richard Mathers' biography as that of an exemplary godly man, a Puritan imitatio Christi . The defining thought figure of the biography is the image of Mather as a father - as the natural father of his son on the one hand, but also in a broader sense as the spiritual father of Dorchester and all of New England, so that he finally gains the stature of an Old Testament prophet.

Such a typological elevation of the “founding fathers” of New England also characterizes the biographies in Cotton Mather's Magnalia Christi Americana , which is still considered the culmination of New England historiography. Cotton Mather was all too aware of the reputation of his ancestors, so in the chapter devoted to Richard Mather's biography he pondered the inheritance of grace .

Works

Mather left behind a considerable number of manuscripts, mostly sermons and letters. A large part of these writings is kept by the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, a part also in the Boston Public Library , and individual manuscripts are scattered across other American libraries. The most extensive bibliography of both manuscripts and published works can be found in:

- Thomas J. Holmes: The Minor Mathers, A List of their Works . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1940.

The following treatises by Mathers were printed:

- An Answer to Two Questions: Whether Does the Power of Church Government Belong to all the People or to the Elders Alone. Boston 1712.

- An Apology of The Churches in New England for Church Covenant. London 1643.

- A Catechisme or, The Grounds and Principles of Christian Religion. London 1650.

- Church Governmant and Church Covenant Discussed, In an Answer of the Elders of the Several Churches in New-England to Two and Thirty Questions. London 1643

- A Defense of the Answer and Arguments of the Synod met at Boston in the Year 1662. Cambridge, Mass. Bay 1664.

- A Disputation Concerning Church-Members and Their Children in Answer to XXI Questions. London 1659.

- A Farewel-Exhortation to the Church and the People of Dorchester in New England. Cambridge, Mass. Bay 1657.

- with William Thompson: An Heart-Melting Exhortation, Together with a Cordiall Consolation, Presented in a Letter from New-England, to Their Dear Countrymen of Lancashier. London 1650.

- with William Thompson: A Modest and Brotherly Answer to Mr. Charles Herle his Book, Against the Independency of Churches.

- A Platform of Church Discipline Gathered out of the Word of God. Cambridge, Mass. Bay 1649.

- A Reply to Mr. Rutherford, or, A Defense of the Answer to Reverend Mr. Herles Booke Against the Independency of Churches. London 1646.

- The Sum of Certain Sermons upon Genes: June 15, Cambridge, Mass. Bay 1652.

- To The Christian Reader. Foreword to John Eliot and Thomas Mayhew: A Further Narrative of the Progress of the Gospel Amongst the Indians in New England. London 1653.

- Will . In: New England Historical and Genealogical Register 20, 1855.

Mather's diary was first published in 1850:

- Journal of Richard Mather Collections of the Dorchester Antiquarian and Historical Society, D. Clapp, Boston 1850.

literature

- BR Burg: Richard Mather . Twayne, New York 1982, ISBN 0-8057-7364-9 (= Twayne's United States Authors Series (TUSAS), Volume 429).

- BR Burg: The Ideology of Richard Mather and Its Relationship to English Puritanism Prior to 1660 . In: Journal of Church and State . Volume 9, Issue 3, 1967, pp. 364-377.

- Michael G. Hall: The Last American Puritan. The Life of Increase Mather 1639-1723 . Wesleyan UP, Middletown CN 1988, ISBN 0-8195-5128-7 .

- Horace E. Mather: Lineage of Rev. Richard Mather . Case, Lockwood & Brainard, Hartford 1896.

- Robert Middlekauff : The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals . Oxford University Press, New York 1971, ISBN 0-520-21930-9 .

- William J. Scheick (Ed.): Two Mather Biographies: Life and Death and Parentator . Lehigh UP, Bethlehem PA 1989, ISBN 0-934223-06-8 (contains Increase Mathers The Life and Death of that Reverend Man of God, Mr. Richard Mather ).

Remarks

- ^ Richard Holman: Seventeenth-Century American Prints. In: John D. Morse (Ed.): Prints in and of America to 1850 . University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville 1970, pp. 25f.

- ^ Sinclair Hamilton: Early American Book Illustrators and Wood Engravers, 1670-1870: A Catalog of a Collection of American Books, Illustrated for the Most Part with Woodcuts and Wood Engravings, in the Princeton Library. Volume I. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1968, pp. 1f.

- ^ Horace E. Mather: The Lineage of Rev. Richard Mather. Hartford CT, 1890. p. 27.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , p. 15.

- ↑ Michael G. Hall: The Last American Puritan , p. 6.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , p. 16.

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , p. 10

- ^ Paul Marston: History of Jeremiah Horrocks. (No longer available online.) In: IAU Colloquium 196: Transit of Venus: New Views of the Solar System and Galaxy, Conference. University of Central Lancashire, June 8, 2003, archived from original ; accessed on April 22, 2019 (English).

- ↑ Michael G. Hall: The Last American Puritan , p. 11.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , p. 21 ff.

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , p. 14.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , pp. 18-19.

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , pp. 22-25.

- ↑ Cotton Mather: Magnalia Christi Americana: Or, The Ecclesiastical History of New England . Silas Andrus & Son, Hartford 1853. Vol. I, p. 450.

- ↑ Michael G. Hall: The Last American Puritan , pp. 17-21.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , pp. 50–51.

- ↑ The Bay Psalm Book ( Memento of the original from September 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ BR Burg: Richard Mather , p. 32.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Mathers , pp. 53-55.

- ↑ RB Burg: Richard Mather , pp. 35–48.

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , pp. 116, 121.

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , p. 81 .: the most influential of all seventeenth-century American ecclesiastical documents

- ↑ RB Burg: Richard Mather , pp. 85–92

- ^ RB Burg: Richard Mather , pp. 108-114.

- ↑ William J. Scheick: Two Mather Biographies , p.20

- ↑ William J. Scheick: Two Mather Biographies , pp. 11-21 passim

- ↑ William J. Scheick: Two Mather Biographies , p.12

- ↑ Cotton Mather: Magnalia Christi Americana: Or, The Ecclesiastical History of New England . Silas Andrus & Son, Hartford 1853. Vol. I, p. 456.

- ↑ Bibliography based on RB Burg: Richard Mather , p. 132 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Mather, Richard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English clergyman and representative of the first generation of Puritans in New England |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1596 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lowton , Lancashire |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 22, 1669 |

| Place of death | Dorchester , Massachusetts |