Salvator mundi (painting)

|

| Salvator mundi |

|---|

| Leonardo da Vinci (attributed to) , around 1500 |

| oil on wood |

| 66 × 46 cm |

| Louvre Abu Dhabi , Abu Dhabi |

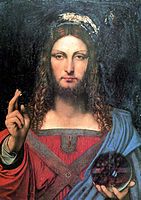

Salvator mundi ( Latin for “ Redeemer of the World” or “ Savior of the World”) is the title of a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci . The oil painting shows Christ as Savior of the world and is dated to around 1500.

The provenance of the painting is only incompletely documented. Isolated mentions can be found for the period from the middle of the 17th century to 1763. Subsequently, the work was considered to have disappeared for a long time. Further evidence can only be found after 1900, although the painting was ascribed to a student from Leonardo's circle at that time.

In 2005 the work was acquired by the art dealer Robert Simon and others who arranged for restorations and investigations. Various expert opinions came to the conclusion that it was a work by Leonardo da Vinci. At the same time, there were different assessments, for example based on a workshop work - and thus only a co-authorship of Leonardo. Regardless of this, the painting achieved record sums in subsequent auctions. With a sales value of 450.3 million US dollars (including fees such as buyer's premium; exactly 400 million US dollars net) at Christie's in New York on November 15, 2017, it is currently the most expensive painting that was ever auctioned. It is privately owned.

description

The 65.6 × 45.4 cm painting is painted with oil paints on a walnut wood panel. It shows Christ as the Savior of the world in a frontal view, who has raised his right hand in a gesture of blessing and is holding a crystal ball in his left.

Provenance

The time of creation, the commissioner or the original location of the painting are unknown. However, it is dated to around 1500.

1649–1763: Royal Collection

The painting is said to have belonged to King Charles I of England , in whose collection it was recorded in 1649. After the execution of Charles I, the painting is said to have been sold. Later it was restituted to the royal collection and finally went to the Duke of Buckingham, whose son had the painting auctioned in 1763, whereupon its trace is lost. In 2018, research for the book “The Last Leonardo” by Ben Lewis revealed that this entry in the directory of Charles I's collection probably refers to a painting by Giampietrino that is now in the possession of the Moscow Pushkin Museum .

20th century: Private collection as a work from the circle of Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio

After 1900 there is evidence that the painting was in the art collection of the English textile merchant family Cook. The painting was then regarded as a work from the circle of the Leonardo pupil Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio . In 1958, Cook's descendants auctioned the painting for £ 45. It was henceforth privately owned by the United States and was acquired in 2005 by a consortium of various art dealers, including Robert Simon from New York.

21st century: restoration, rewrite to Leonardo da Vinci and auction to unknown bidder

Before the presentation at the Leonardo exhibition in 2011 in the National Gallery (under the curator Luke Syson) the painting was extensively restored by Dianne Dwyer Modestini in New York. Modestini is a Conservator and Senior Research Fellow at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts (IFA) at New York University , had just completed the restoration of a Madonna and Child by Andrea del Sarto when Robert Simon entrusted the painting to her in 2005, and published it in 2014 a short report with technical details about the painting. She considers it a work by Leonardo herself. In 2012 it was presented at the Dallas Museum of Art .

In 2013 the auction house Sotheby’s brokered a private sale of the painting to the dealer Yves Bouvier , who is said to have paid 80 million US dollars for it. In the same year he sold the painting to the collector Dmitri Evgenyevich Rybolovlew for US $ 127.5 million . Up to this date, the picture was the only presumed painting by Leonardo in private hands.

The Christie’s auction house auctioned the work on November 15, 2017 in New York. The estimated price was previously estimated at around 100 million dollars. An estimated 27,000 people saw the painting as part of the previous exhibition of the work by the auction house in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York. It was finally awarded after around 45 bids at 400 million US dollars. The painting Salvator Mundi was sold for a record amount of around 450.3 million US dollars (the equivalent of around 382 million euros) to an unnamed bidder for a fee. According to the auction house, it is the most expensive work of art ever auctioned .

In December 2017, it was reported that the painting was auctioned by two investment companies that have a financial deal with several major museums and that it will be shown in the Louvre Abu Dhabi in the future . In June 2019 it was reported to be owned by the Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman .

An exhibition in the Louvre Abu Dhabi that had been announced for September 2018 was canceled at short notice without a reason and postponed indefinitely. The painting was also not shown at the Leonardo exhibition in Paris in October 2019.

Restoration and appraisal

More than twenty copies and an engraving by the Bohemian graphic artist Wenceslaus Hollar from 1650 suggested that Leonardo da Vinci had also painted or prepared the motif of a Salvator mundi . Two sketches of the drapery of the robe, which are in the Royal Library in Windsor and can be attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, also substantiate this assumption. As early as the 1980s, the art historian Joanne Snow-Smith tried to prove the authenticity of a Salvator mundi supposedly by Leonardo , who was then in the possession of the Marquis de Ganay, but was unable to convince her colleagues. Today the Salvator mundi from the Ganay collection is considered a copy.

Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar ,

17th centuryStudy of Leonardo da Vinci's robe for a Salvator mundi, c. 1504-08, Royal Collection , Windsor

The painting was in very poor condition, with disfiguring overpaintings from previous restorations, when it was presented to New York art dealer and art historian Robert Simon in 2005. Simon, who at the time suspected a high-quality original but not a work by Leonardo, arranged for a careful restoration. It was only after the original painting was uncovered in 2007 that the painting was presented to several experts for assessment.

Mina Gregori ( University of Florence ) and Nicholas Penny (Director of the National Gallery in London, at that time still curator of the sculptures in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC ) examined the panel as early as 2007. Then, according to Christie's Andrea Bayer, Keith Christiansen, Everett Fahy and Michael Gallagher, curators of the Metropolitan Museum of Art , with the painting. In May 2008 the painting was brought to the National Gallery in London in order to be able to compare it directly with Leonardo's Rock Grotto Madonna , who must have been created around the same time. Several Leonardo experts were invited to view the painting there, including Carmen Bambach, David Alan Brown, Maria Teresa Fiorio, Martin Kemp , Pietro C. Marani and Luke Syson . In 2010, the conservation work on the board was finally completed. The picture was then examined again. A majority of these experts came to the conclusion that this is Leonardo da Vinci's authentic original, from which all known copies can be derived.

The expert reports on the attribution to Leonardo da Vinci consulted by Christie's are based on arguments critical of style, the material-technical investigations and in particular on the analysis of numerous pentimenti , i.e. those changes that the artist himself made to his work. The comparison with the two studies of robes that Leonardo apparently created in preparation for the painting also helped to secure the attribution. Furthermore, the superiority of the original becomes apparent when compared with the more than twenty known copies of the painting.

According to the art historian Frank Zöllner , the sfumato typical of Leonardo was only added during the restorations between 2005 and 2017. Walter Isaacson , who presented a biography of Leonardo in 2018, assumed that Leonardo represents a hollow, thin-walled glass sphere. In the opinion of Carmen Bambach , curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the painting was made by Leonardo's assistant, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, with some minor retouching by the master's hand.

In computer graphics simulations at the University of California, Irvine , three-dimensional virtual versions of the glass ball in the Salvator's hand were created using Inverse Rendering software. The investigation of the refraction of light that occurred in each case showed that the sphere serving as a template must not have been solid, but hollow. For a glass ball with a wall thickness of 1.3 millimeters, the simulation provided exactly the appearance of the ball in the painting. In addition, the sphere had to have a radius of 6.8 centimeters and was held 25 centimeters away from the body. The viewing point from which Leonardo da Vinci observed the model was about three feet away.

meaning

It is one of only around 15 oil paintings by Leonardo da Vinci that have survived and is the first rewriting of an original to Leonardo da Vinci since the painting of Madonna Benois was found in 1909 and is now in the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg .

The composition of the painting bears a remarkable resemblance to the Salvator Mundi by Melozzo da Forli in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino (1480/82), in which Heydenreich (1964) already saw the possible model for Leonardo's picture. According to Heydenreich, there was not necessarily a painting by Leonardo on the subject, but possibly just a cardboard sketch that was used by his students as a template for paintings to which he occasionally contributed.

Since the painting was published, however, numerous experts have spoken out against the attribution of the painting to Leonardo or his sole authorship. These include Charles Hope (former director of the Warburg Institute , London), Carmen Bambach (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Charles Robertson ( Oxford Brookes University ) and Frank Zöllner (author of the main catalog of Leonardo's paintings). According to Zöllner, the attribution is primarily unclear for two reasons: On the one hand, the picture was subjected to an extensive restoration, so that the original quality is very difficult to assess; on the other hand, it uses a sfumato technique, which is more similar to that of his students in the 1520s Years. To make matters worse, the restorer made changes between the painting's exhibition in London in 2011 and its sale in 2017. This applies above all to the folds of the garment on the right side of the picture. Various details (hand and fingernails, crystal ball, hair, robe, heavy eyelids and shaded eyes) and the treatment of light speak, according to Zöllner, in favor of Leonardo's involvement. In his opinion, the quality of the painting is superior to the other well-known Salvator mundi variants from the Leonardo school . Like Heydenreich, he sees Leonardo's model in a Salvator Mundi by Melozzo da Forlì in the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino and advocates dating after 1502 (and even after 1507) (from this time stays in Urbino can be proven). The curator of the National Gallery, Luke Syson , who presented the picture at his exhibition in 2011, spoke out in favor of the authorship of Leonardo and dated it to the time before 1500.

See also

literature

- Ludwig H. Heydenreich : Leonardo's "Salvator Mundi". Raccolta Vinciana, Vol. 20, 1964, pp. 83-109.

- Joanne Snow-Smith: The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo da Vinci. Henry Art Gallery, Seattle 1982. ISBN 0-935558-11-X

- Luke Syson , Larry Keith et al. a .: Leonardo da Vinci. Painter at the Court of Milan. National Gallery exhibition catalog. London 2011, pp. 282 f., 298-303, catalog no. 91.

- Frank Zöllner : This picture is in a different league. In: FAZ , July 10, 2011.

- Gina Thomas: He saves the world with a hand of blessing. In: FAZ , July 11, 2011.

- Frank Zöllner: A double Leonardo. On two exhibitions (and their catalogs) in London and Paris. In: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 3 (2013), pp. 417–427 (English).

- Frank Zöllner: Lesson for $ 80 million. In: Die Zeit , April 3, 2014.

- Nicola Barbatelli, Margherita Melan, Carlo Pedretti (eds.): Leonardo a Donnaregina. I “Salvator Mundi” per Napoli . Catalog for the exhibition of the Museo Diocesano di Napoli, January 12 - March 30, 2017. CB Edizioni, 2017. ISBN 978-88-7369-107-5 . - In it: Carlo Pedretti: Il Salvatore, questo sconosciuto , pp. 15–41 .

- Frank Zöllner : Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519. All paintings. Taschen, Cologne 2017. ISBN 978-3-8365-6294-2

- Frank Zöllner: How old is this master? In: Art. Das Kunstmagazin , February 2018, pp. 68–71.

- Frank Zöllner: Salvator Mundi: The most expensive flop in the world? In: Die Zeit , No. 2, January 3, 2019 ( online ).

- Ben Lewis : The Last Leonardo. The making of a masterpiece . London: Harper, Collins 2019. ISBN 978-0-00831342-5

- Martin Kemp , Robert B. Simon, Margaret Dalivalle: Leonardo's Salvator Mundi and the Collecting of Leonardo in the Stuart Courts . Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press 2019. ISBN 978-0-19881383-5

- Charles Nicholl : The Last Leonardo by Ben Lewis review - secrets of the world's most expensive painting The Guardian, April 17, 2019

Web links

- The Last da Vinci , at: Christie's , October 10, 2017 (English).

- Milton Esterow: Updated: A Long Lost Leonardo. ( Memento of July 9, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) In: ARTnews , July 11, 2011 (English).

- Hasan Niyazi: Authorship and the danger of consensus. In: 3PP , July 11, 2011 (English).

- Hasan Niyazi: Platonic receptacles, Leonardo and the Salvator Mundi. In: 3PP , July 18, 2011 (English).

Individual evidence

- ^ Frank Zöllner: A double Leonardo. On two exhibitions (and their catalogs) in London and Paris. In: Journal for Art History . tape 3 , 2013, p. 417-427, here p. 420 ff . (English, online [PDF; accessed December 11, 2017]).

- ^ Frank Zöllner: Lehrstück for 80 million dollars. In: The time. April 3, 2014, accessed December 11, 2017 .

- ^ Michael Daley: Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi. Part I: Provenance and Presentation. In: ArtWatch UK online. November 23, 2016, accessed December 11, 2017 .

- ^ A b c Robert Simon: Da Vinci discovered , in: PR Newswire , July 7, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d Gina Thomas : He saves the world with a blessing hand , in: FAZ , July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Kia Vahland: "Salvator Mundi": origin unclear , Süddeutsche Zeitung, December 2, 2018

- ↑ Leonardo da Vinci, Painter at the Court of Milan. Exhibition from November 9, 2011 to February 5, 2012 at the National Gallery, London, accessed November 10, 2018.

- ↑ Megan Doll: The lost Leonardo. A master's priceless work is found , in: NYU Alumni Magazine 2011.

- ↑ Keri Geiger: Sotheby's, a Prized Art Client and His $ 47.5 Million da Vinci Markup , in: Bloomberg.com , November 30, 2016.

- ↑ mja: Lost painting at Christie's: Da Vinci work could bring in 100 million dollars , in: Spiegel online , October 11, 2017.

- ↑ a b Records at the start of the New York autumn auctions . Monopoly magazine. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ↑ aar / dpa: Da Vinci painting auctioned for $ 450,312,500 , in: Spiegel online , October 16, 2017.

- ↑ The most expensive painting in the world will hang in Abu Dhabi in future , in: sueddeutsche.de , December 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Salvator Mundi" is probably on the Prinzen-Yacht. In: Tagesspiegel. June 11, 2019, accessed October 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Saeed Kamali Dehgha: Louvre Abu Dhabi postpones display of Leonardo's Salvator Mundi , in: The Guardian , September 3, 2018, accessed November 10, 2018.

- ↑ Torsten Landsberg: Louvre has to do without pictures by Leonardo da Vinci Deutsche Welle, October 24, 2019, accessed on October 29, 2019

- ↑ Rose-Maria Gropp: Leonardo in Paris: He is not there faz.net, October 28, 2019, accessed on October 31, 2019

- ↑ a b c d The Last da Vinci , at: Christie’s , November 12, 2017.

- ↑ a b Dalya Alberge: Leonardo da Vinci expert declines to back Salvator Mundi as his painting , The Guardian, June 2, 2019, accessed June 6, 2019

- ↑ Frank Zöllner: The most expensive flop in the world? In: Die Zeit , January 3, 2019, p. 45.

- ↑ a b Helga Rietz: Computer scientists agree with da Vinci. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Research and Technology, January 15, 2020

- ↑ Painting: Researchers decipher Da Vinci's mysterious glass ball . Technology Review online, TR Online January 10, 2020.

- ↑ Marco Liang, Michael T. Goodrich, Shuang Zhao: On the Optical Accuracy of the Salvator Mundi . December 6, 2019, arxiv : 1912.03416 .

- ↑ Figure

- ↑ Customs officer: Leonardo da Vinci. Taschen, Cologne 2017, p. 443.

- ^ Michael Dalley: Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi. Part I: Provenance and Presentation , in: ArtWatch UK online , November 14, 2017.

- ^ Charles Robertson: Leonardo da Vinci: London 2012. In: The Burlington Magazine , No. 154, 2012, pp. 132 f.

- ^ Frank Zöllner: Catalog number XXXII, Salvator Mundi. (PDF) In: Leonardo da Vinci 1451–1519. All paintings and drawings, Cologne. Frank Zöllner, 2017, pp. 440–445 , accessed on December 11, 2017 .

- ^ Frank Zöllner: Preface to the 2017 edition . In: Frank Zöllner (Ed.): Leonardo da Vinci 1451-1519. All paintings . Cologne 2017, p. 6–17, here p. 15 ff . (English, online [PDF; accessed December 11, 2017]).

- ^ Frank Zöller: Preface to the revised edition of 2018 . In: Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings . Cologne 2018 (English, online [PDF; accessed on September 10, 2018]).

- ^ Illustration of a Salvator Mundi attributed to Melozzo da Forli . The different painting by da Forli in the ducal palace of Urbino is in Frank Zöllner: Leonardo da Vinci 1451-1519. All paintings and drawings , Cologne 2017, p. 16, illustrated.

- ↑ Customs officer: Leonardo da Vinci. Taschen, p. 443 f.