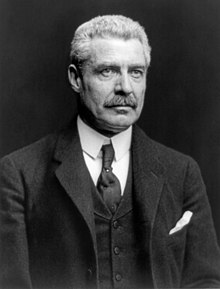

Samuel Rea

Samuel Rea (born September 21, 1855 in Hollidaysburg , † March 24, 1929 in Philadelphia ) was an American railroad engineer and entrepreneur. He worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) for over 40 years and was its ninth President between 1913 and 1925. At the beginning of the 20th century, he was instrumental in the realization of the first railroad connection in New York City between New Jersey , Midtown Manhattan and Long Island , with tunnels under the Hudson River and East River , and connected that with the construction of the Hell Gate Bridge in 1917 Finally, the PRR network with New England . The rail link is now part of the Northeast Corridor , which runs over New York City and is the only major electrified long-distance rail line in the United States. In 1926, Rea was awarded the Franklin Medal for his achievements .

Life

Samuel Rea was born on September 21, 1855 in Hollidaysburg, the second son of James D. and Ruth Blair Rea, née Moore. His great-grandfather, Samuel Rea, had come to the United States from northern Ireland around 1755 and settled in Pennsylvania. His grandfather John Rea was Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania Militia and from 1803 for several years a member of the House of Representatives of the United States and from 1823 to 1824 in the Senate of Pennsylvania . His father, James D. Rea, originally a teacher, worked for the canal authority in Hollidaysburg and later became a warehouse manager. He died in 1868 at the age of 57 when Samuel was 13 years old, who in addition to his brother Thomas Blair Rea had a sister, Jane Moore Rea.

Engineer for various railway companies

After his father's death, Samuel Rea dropped out of school and began working as a surveyor's assistant on the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) at the age of 16 in 1871, working on various lines in Blair County . His employment ended with the founding crash of 1873 and he worked in a hardware factory for two years. From 1875 he was assistant engineer in Pittsburgh building the first point bridge over the Monongahela River , which was completed in 1877. After that he was involved in the construction of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad , founded in 1875, for a few years , but went back to the PRR after its completion in 1879 and worked on the expansion of the Pittsburgh, Virginia and Charleston Railway, acquired in 1872, south of Monongahela and on lines of the PRR in Westmoreland County . With the rise of his boss JN DuBarry to Vice President of the PRR in 1883, Samuel Rea became his personal assistant in Philadelphia, a position he held until 1888.

Ascent on the Pennsylvania Railroad

Dissatisfied with the development of his career with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Rea moved to the Maryland Central Railroad Company in 1889 , where he became Vice President. In addition, he was chief engineer of the Baltimore Belt Line and dealt for the first time with tunnel construction and electric locomotives , since coal-powered locomotives were unsuitable for long tunnel journeys. For health reasons, however, he had to give up his engagement after two years. After his recovery, those in charge of the PRR who had lost him to the competition were interested in his reinstatement, and Samuel Rea became personal assistant to then President George Brooke Roberts in 1892 . In the same year he commissioned him to investigate the London public transport system of the City and South London Railway during his vacation in England , in particular the tunnels used under the Thames as a possible variant for the realization of a connection between New Jersey and Midtown Manhattan under the Hudson River .

Rea worked with the later President of the PRR Alexander J. Cassatt (1899-1906) for several years on a solution for a rail link to Manhattan and favored the North River Bridge proposed by the bridge engineer Gustav Lindenthal . He had previously founded the banking company Rea Brothers & Company with his brother , took an active part in the possible financing of the bridge and was a partner in the North River Bridge Company . Within the PRR, Rea rose to the fourth vice-president in 1899, the third in 1905 and the second in 1909, and was also president or vice-president of several smaller railway companies.

Rail connection to Manhattan

Due to the immense cost of the planned bridge over the Hudson, the participation of all railway companies that served New York City was necessary. Because of this fact, the project finally failed in 1901 and the PRR looked for its own self-financed solution under the current President Cassatt. When Cassatt was staying with his sister Mary Cassatt in Paris in the summer of the same year , Samuel Rea suggested that he visit the Gare d'Orsay, built for the 1900 World's Fair . The building in the style of Beaux Arts architecture with its lowered platforms was to become the template for the later New York Pennsylvania Station and the PRR now opted for a tunnel solution.

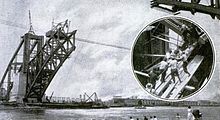

The English tunnel expert Charles M. Jacobs was hired for the implementation and a connection from Weehawken to Manhattan and finally to Queens , where the Long Island Rail Road , acquired by the PRR in 1900 , was to be connected. Under Rea's direction, the North River Tunnels under the Hudson and the East River Tunnels under the East River were built between 1904 and 1910 as part of the New York Tunnel Extension . In Manhattan, the routes on which exclusively electrical operation was planned were combined in Penn Station, which was also completed in 1910.

The rail link built by PRR is now part of the Northeast Corridor , with the track in Manhattan including Penn Station being largely overbuilt over the past hundred years; the historic station building was torn down in 1963. The underground Penn Station, completed in 1968, is now the busiest passenger station in the United States, with around 600,000 passengers a day. The Sunnyside Yard in Queens, which was also built in 1910 as part of the New York Tunnel Extension, is required for operation and is still used for the maintenance, formation and supply of Amtrak long-distance trains and local trains in New Jersey Transit . As part of Harold Interlocking, it is the largest rail hub for passenger traffic in North America, with almost 800 trains passing through the area of the depot every day .

Northeast Corridor with Penn Station and Sunnyside Yard ( turning loop ) [subterranean course in dashed lines]

President of the Pennsylvania Railroad

In 1913, Samuel Rea became the ninth President of the Pennsylvania Railroad and served in this position until his retirement in 1925. During this time, in 1917, with the completion of the Hell Gate Bridge over the East River designed by Gustav Lindenthal , the remaining connection to the Long Island Rail Road to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad . As a result, the PRR network was finally connected to New England , a stretch of the route that is now the Northeast Corridor to Boston . At its peak in 1920, the company had 279,000 employees and an 11,100- mile route network that totaled 28,000 miles, including any minor railroad companies and route rights acquired . At that time, the PRR operated 6,700 trains a day, which carried 10% of the freight traffic and 20% of the passenger traffic in the USA.

When the USA entered the First World War in 1917, all railway companies were placed under state control and united in the United States Railroad Administration . Rea campaigned for its repeal, which was carried out in 1920 by the Esch-Cummins Act and led to the establishment of the Railroad Labor Board , to settle disputes between the growing unions and the railroad companies. A massive cut in workers' salaries approved by the Board led to a major rail strike in 1922, in which 400,000 railway depot workers across the country went out of work. The PRR responded by large-scale relocation and hiring of thousands of workers to keep operations going. Only after two months could the strike be ended by state intervention.

family

Samuel Rea married Mary M. Black on September 11, 1879, daughter of George Black, who also worked for the PRR. They had a son and a daughter. George Black Rea was born in 1880 and later, like his father, worked as an engineer for the PRR. During the tunnel construction project under the Hudson River, he contracted pneumonia, from which he died in 1908. His sister Ruth Rea was born in 1891. From 1885 to 1914 the family lived in Bryn Mawr , in the former home of the architect Addison Hutton , and then moved to the new Waverly Heights estate in the Gladwyne suburb of Philadelphia, which was built for them from 1912 . Three years after his retirement, Samuel Rea died in his home on March 24, 1929. After the death of his wife in 1933, the property was passed on to his daughter and her husband George Junkin. Ruth Rea Junkin lived here until 1981 (she died in 1983), today Waverly Heights is a retirement home.

In memory of Samuel Rea, a bronze statue was created in 1930 by the sculptor Adolph Alexander Weinman , which was unveiled in the entrance area of the then main building of Penn Station and is located at the entrance to the now subterranean station on Seventh Avenue. In the mid-1950s, the PRR built a large railway depot in Rea's hometown Hollidaysburg , which is named Samuel Rea Shop in his honor .

literature

- William Couper (Ed.): History of the engineering, construction, and equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York terminal and approaches ... Isaac H. Blanchard Company, New York 1912.

- Jill Jonnes: Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and its Tunnels. Penguin Books, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-14-311324-9 .

- John W. Jordan (Ed.): Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania. Lewis Pub. Co., 1911. Reprint: Clearfield, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8063-5239-8 , pp. 639-643.

- Vincent Tirolo Jr .: Tunneling Under the Hudson and East Rivers in the Early 1900s: Risk Identification and Management Lessons That Are Still Useful Today. In: North American Tunneling: 2014 Proceedings. SME, 2014, ISBN 978-0-87335-400-4 , pp. 139-150.

Web links

- Samuel Rea (1855-1929). Johnstown Flood National Memorial, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior.

- Rea, Samuel (1855-1929). Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Individual evidence

- ↑ John W. Jordan (Ed.): Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania. Lewis Pub. Co., 1911. Reprint: Clearfield, 2004, pp. 639-641.

- ↑ a b c d e Samuel Rea (1855–1929). Johnstown Flood National Memorial, National Park Service, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ↑ John W. Jordan (Ed.): Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania. Lewis Pub. Co., 1911. Reprint: Clearfield, 2004, p. 641.

- ^ A b Jill Jonnes: Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and its Tunnels. Penguin Books, 2008, pp. 39-42.

- ↑ John W. Jordan (Ed.): Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania. Lewis Pub. Co., 1911. Reprint: Clearfield, 2004, p. 642.

- ↑ Jill Jonnes: Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and its Tunnels. Penguin Books, 2008, pp. 53-58.

- ↑ Jill Jonnes: Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and its Tunnels. Penguin Books, 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Albert J. Churchill Ella: The Pennsylvania Railroad, Volume 1: Building an Empire, 1846-1917. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8122-0762-0 , p. 704.

- ^ Harold Interlocking Northeast Corridor Congestion Relief Project. Metropolitan Transportation Authority, accessed February 15, 2020.

- ↑ What is Sunnyside Yard? Sunnyside Yard Master Planning Process, New York City Economic Development Corporation, 2018, accessed February 15, 2020.

- ^ Donald E. Wolf: Crossing the Hudson: Historic Bridges and Tunnels of the River. Rutgers Univ. Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-8135-4708-4 , pp. 129 f.

- ↑ Dan Cupper, Charles Hardy III, Patricia Brett: The Railroad in Pennsylvania. Stories from PA History, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Chapter Two: The Pennsylvania Railroad: "Standard of the World." Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ Colin J. Davis: Strategy for Success: The Pennsylvania Railroad and the 1922 National Railroad Shopmen's Strike. In: Business and Economic History. Vol. 19, 1990, pp. 271-278.

- ↑ John W. Jordan (Ed.): Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania. Lewis Pub. Co., 1911. Reprint: Clearfield, 2004, p. 643.

- ↑ a b Burial Records. Church of the Redeemer, Lower Merion Historical Society. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ↑ Elizabeth Biddle Yarnall: Addison Hutton: Quaker Architect, 1834-1916. Associated University Presse, 1974, ISBN 978-0-87982-013-8 , pp. 69 and 75.

- ↑ Waverly Heights. Samuel Rea Estate, Gladwyne-Aerial View, Lower Merion Historical Society. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ William Bates, Jr .: A History of Waverly Heights. Waverly Heights Ltd., 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Dianne L. Durante: Samuel Rea. In: Forgotten delights. Retrieved April 9, 2015 .

- ^ John C. Paige: History of the Altoona Railroad Shops. America's Industrial Heritage Project, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1989. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ The Pennsylvania Railroad Board of Directors Inspection Trip. Pennsylvania Railroad, Oct 1957, pp. 27-30. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rea, Samuel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American engineer and entrepreneur |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 21, 1855 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hollidaysburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 24, 1929 |

| Place of death | Philadelphia |