East River Tunnels

| East River Tunnels | ||

|---|---|---|

|

East River Tunnel Tube No. 4

|

||

| use | Railway tunnel | |

| traffic connection | Northeast Corridor | |

| place | Manhattan and Long Island City , New York City | |

| length | 1830 m | |

| Number of tubes | 4th | |

| cross-section | 74 m² | |

| construction | ||

| Client | Pennsylvania Railroad | |

| building-costs |

entire New York Tunnel Extension : 100 million dollars |

|

| start of building | May 17, 1904 | |

| completion | May 17, 1909 | |

| planner | Alfred Noble | |

| business | ||

| operator | Amtrak | |

| release | November 28, 1910 | |

| Situation map | ||

|

||

| location | ||

|

|

||

| Coordinates | ||

| Ventilation shaft Manhattan tubes No. 1 and 2 |

40 ° 44 ′ 36 " N , 73 ° 58 ′ 25" W. | |

| Ventilation shaft Manhattan tubes No. 3 and 4 |

40 ° 44 ′ 34 " N , 73 ° 58 ′ 25" W. | |

| Long Island Portal Tube No. 1 | 40 ° 44 ′ 35 " N , 73 ° 56 ′ 45" W. | |

| Long Island Portal Tube No. 3 | 40 ° 44 ′ 31 ″ N , 73 ° 56 ′ 54 ″ W. | |

| Long Island Portal Tube # 2 and # 4 | 40 ° 44 ′ 35 " N , 73 ° 56 ′ 42" W. | |

The East River Tunnels , often referred to simply as the East River Tunnels , are four approximately 1,830 m long railway tunnels opened in 1910 , which lead from Manhattan under the East River to Queens in New York City . They each consist of a 1,190 m long underwater tunnel , the actual East River Tunnel and a 610 m long access tunnel on the east side, which opens into the Sunnyside Yard in Long Island City . The East River Tunnels are part of the Northeast Corridor and are also known as the Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnels along with the Crosstown Tunnels and the North River Tunnels .

meaning

The East River Tunnels are the eastern entrance to New York Pennsylvania Station , or Penn Station for short , in Manhattan. They are used daily by approximately 600 suburban trains on the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and long-distance trains on the Amtrak . These run from Long Island over the Hell Gate Bridge in the direction of New England . The East River Tunnels are also used by the New Jersey Transit trains , which use the Sunnyside Yard as a parking area .

history

In the early days of railroad history, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) had no direct access to Manhattan. The main route from Philadelphia to New York City ended in Jersey City at Exchange Place Station on the west bank of the Hudson River . The travelers had to take a ferry across to Manhattan. Several projects tried to create a direct connection for the PRR to Manhattan, where a new terminus was to be built. With the takeover of Long Island Rail Road by the PRR, new opportunities arose. The station could now also be the end point of local traffic from Long Island, but also serve as a through station for long-distance trains from Philadelphia via New York to New England.

At the end of the 19th century, electric traction reached a maturity that made it possible to electrify mainline railways , even if the projects were still modest. The electric locomotives were able to negotiate steeper gradients more easily than the steam locomotives and the tunnels remain smoke-free, so the effort for tunnel ventilation could be kept low. After the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had good experiences with the electric operation in the Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore and Alexander Cassatt , the then President of the PRR, had visited the Gare d'Orsay of the PO in Paris , the PRR worked on a project for one new magnificent train station in Manhattan, which should be reached with underground access.

The project was called the New York Tunnel Extension and planning began in 1901. The centerpiece was the new Pennsylvania Station to be built in Manhattan. The western approach leads through the North River Tunnels, the eastern one through the East River Tunnels. The new line to be built from Newark in New Jersey crosses the alluvial plain of the Hackensack River to the North River Tunnels, which led under the Hudson to Penn Station. East of Penn Station are the Crosstown Tunnels, which lead the route to the west coast of the East River. With an arch to the north, the East River Tunnels continue under the river of the same name through to Sunnyside Yard in Queens .

The estimated costs for the entire New York Tunnel Extension between Harrison and Sunnyside Yard, including Penn Station, were estimated at 100 million US dollars , the actual costs were 150 million US dollars, which equates to a purchasing power of 4 billion US dollars in 2020 corresponded.

The New York Tunnel Extension opened on November 27, 1910. The trains ran electrically on the entire route, the power supply for the locomotives and railcars was provided by a third rail with a direct voltage of 650 V. The Long Island Railroad had already started partial electrical operation in 1906 as part of the Atlantic Avenue Improvement project in Brooklyn the tracks to the Flatbush Avenue Terminal, further south, were removed from street level on Atlantic Avenue and laid in tunnels or on elevated railway bridges in sections. The LIRR trains no longer ran to Long Island City Station , but used the East River Tunnels to Penn Station. This saved at least some of the commuters from having to change to the Manhattan ferry. The ferry service continued until 1925, as some places in Manhattan were easier to reach by changing to the ferry.

The long-distance trains from the Western hauled by steam locomotives ran to the Manhattan Transfer Station , where the steam locomotives were exchanged for class DD1 electric locomotives , which took the trains through the North River Tunnels to Penn Station. For the time being, all trains ended at Penn Station and after the passengers had disembarked, they were taken through the North River Tunnels to the storage area in Sunnyside Yard. It was not until 1917 that the New York Connecting Railroad was opened over the Hell Gate Bridge, so that long-distance trains could continue to run from Penn Station to New England. From 1933 the trains from Philadelphia ran continuously electrically, with an overhead line with 11 kV 25 Hz alternating current for the energy supply.

In 1967 the PRR merged with New York Central to form Penn Central . This company went bankrupt in 1970. The route of the New York Tunnel Extension with the East River Tunnels was transferred to the newly founded semi-state Amtrak on May 1, 1971 , which also operates long-distance services on the North American rail network.

Hurricane Sandy

The tunnels were flooded with saltwater during Hurricane Sandy in October 2012 , which entered through the ventilation shaft on First Avenue and through the tunnel portals of Tubes 1 and 2 in Long Island City . In the middle of the tunnels the water level reached the ceiling. After the water was pumped out, corrosive chlorides and sulphides remained, which damaged the concrete lining, the verges and the electrical installations in them - a process that continues years after the flooding. Chipped concrete parts lying on the tracks lead to operational disruptions, in winter icicles formed by penetrating water have to be removed regularly . Furthermore, there are more frequent failures of the high-voltage cables and signal cables that are laid in the shoulder.

construction

The planning of the tunnels began in 1901 under the direction of the American civil engineer Alfred Noble . The contract for the construction of the tunnels was awarded in July 1904 to the British construction company S. Pearson & Son . Since no company had previously registered for an award with a fixed-price contract, the contract was drawn up as a profit-sharing agreement so that the risk for the building contractor could be limited. S. Pearson & Son had already built the Blackwall tunnel under the Thames in London and thus had experience in building underwater tunnels.

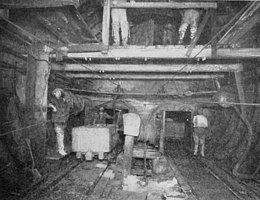

Construction of the East River tunnel was in May 1904. First, a temporary attack bay were ⊙ west of today's Pulaski Bridge drilled in Long Iceland, so in September 1904, the excavation of all four tubes towards East River until a date as a ventilation shaft to be used between attack bay ⊙ took place on the east bank of the river. The tunnel was driven both Sohlstollen after the old Austrian construction as well as with First tunnel after the Belgian design . Behind the outbreak were a tubbing publishing machine the rings of cast-iron lining segments installed to reinforce the tunnel.

In June 1904 the construction of the two ventilation shafts, which served as attack shafts, began on the west bank of the river in Manhattan, in December 1904 the attack took place on the Manhattan side in tubes C and D, tubes A and B followed in July 1905 In the autumn of the same year, enough distance had been excavated in the stable rock so that the compressed air shields and the bulkheads could be installed behind them so that the drives for the excavation of the underwater tunnels could be pressurized for the first time. Between June and October 1906, all pipes were also attacked on the Long Island side. The drive was carried out simultaneously in all four tubes with a total of eight compressed air shields, with work in tube C on the Manhattan side in 1906 being suspended for several months due to a lack of compressed air supply.

During the excavation of the tunnels in the loose rock, the pressure on the tunnel breasts was kept at 2.5 bar and in difficult zones it was temporarily increased to 3 bar. The compressed air supply was ensured from the installation sites in Manhattan ⊙ and Long Island ⊙ . According to the contract, each installation space had to be able to compress at least 8500 m³ to 3.4 bar per hour. For this purpose, seven compressors driven by steam engines were installed in a hall in Manhattan , which were supplied by Ingersoll Rand . In order to treat workers with decompression sickness , decompression chambers were installed at the installation sites, which greatly reduced the number of workers absent.

According to the construction contract, a bulkhead had to be installed in the tunnel tubes at least every 300 m . Each bulkhead was provided with two pressure locks for workers and materials at the bottom, and an emergency pressure lock at the top in the middle. At least 30 meters behind the tunnel face was one of the dome extending into the tunnel barrier. In the event of water ingress, it had the task of enclosing an air bubble under the canopy, which kept the escape route to the rear open for the workers. An elevated catwalk led from the protective wall to the emergency lock in the bulkhead behind it.

The building was encountered sand and clay on the west side and with boulders interspersed clay on the east side of the river in the extension of Roosevelt Iceland lying riffs from gneiss . On the Manhattan side, the cover of the tunnel tube near the river bank was only 2.5 m. In order to prevent the compressed air from escaping into the river during the advance and a pressure drop in the tunnel that would have caused water to penetrate, a 3 to 3.5 m thick clay cover was laid over the course of the tunnel on the river bed. The drives were controlled so that they met in the hard rock of the Roosvelt Island Reef. Each tube was drilled approximately 540 meters from the Manhattan side and 650 meters from the Long Island side. Due to problems with the equipment, difficult ground and limited compressed air supply, the construction work was delayed by about two years; the breakthroughs in the four tubes took place in February and March 1908.

To the east of the temporary attack shaft on Long Island, the tunnels up to the east portals were built using the cut-and-cover method .

Decompression of Ernest William Moir , as she stood on the installation spaces available

Open-cut tunnel tubes west of Sunnyside Yard at the point where tube C runs over tube B. In the back the tube C, in front the ceiling of the tube B

Building

The East River Tunnels consist of four single-track tunnels that are labeled A, B, C and D or numbered 1, 2, 3 and 4 from north to south. In contrast to the two-track west access through the North River Tunnels, the east access was designed with four tracks so that there is enough capacity for the Long Island Rail Road trains and the empty material trains between Sunnyside Yard and Penn Station.

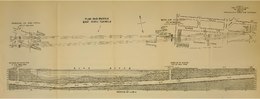

To the west, the tunnels connect to the Cross River Tunnels, which run under 32nd and 33rd Streets. The building boundary runs by the two ventilation shafts that stand east of First Avenue. Two tubes continue from the tunnel on 33rd Street, the other two from the tunnel on 32nd Street. The distance between the two pairs of pipes under the East River becomes smaller towards the east bank, so that only one common ventilation shaft for all four pipes was built at Long Island City Station.

The four tubes run from Manhattan with a 15 ‰ gradient to the deepest point under the river near the west bank, then rise at 7 ‰ against the east bank of the river before rising at 12.2 ‰ to 15 ‰ towards Sunnyside Yard. On the Long Island side, to the east of the Pulaski Bridge, tube C runs over tube B, which is why this tube has a gradient of 19 ‰. Tubes B and D have a common portal, tubes A and C have separate portals, with that of tube C being set back 250 m from the other portals due to the overpass. This made it possible to run the two tracks used by the trains going west together through the Sunnyside Yard, the greater gradient in tube C did not disturb that it is only used by the trains going west.

The outer shells of the underwater tunnels are made up of bolted cast-iron segments that are put together to form rings. Each ring is 2.5 feet (76 cm) wide and weighs 13.6 t, the outer diameter is seven meters. The inner lining of the tunnels is made of concrete and is 56 cm thick.

Along the entire length of the tunnel there are high banquets on both sides, inside of which the power and signal cables run and the roof of which serves as a maintenance and emergency route through the tunnel. The high shoulder should also reduce the tunnel cross-section so that the trains passing through should lead to better ventilation of the tunnels. Every 90 m there are ladders that allow access to the track bed.

Both the 11 kV 25 Hz catenary for the New Jersey transit trains and a power rail for the Long Island Rail Road trains are laid in all tubes . The construction of the catenary was already taken into account when the tunnels were built by providing pockets for the insulators in the inner lining. The catenary is only 15 cm below the vault, which is why the increase in operating voltage is limited.

literature

- William Wirt Mills: The Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnels and Terminals in New York City . In: Moses King (Ed.): King's Booklets . New York 1904, OCLC 1050860090 .

- Alfred Noble: The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The East River Division. Paper No. 1152 . In: American Society of Civil Engineers (Ed.): Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers . tape 68 , September 1910, p. 63-74 ( gutenberg.org ).

- James H. Brace, Francis Mason, SH Woodard: The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159 . In: American Society of Civil Engineers (Ed.): Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers . tape 68 , September 1910, p. 419-478 ( archive.org ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b he East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159. p. 419

- ↑ Albert J. Churchill Ella: The Pennsylvania Railroad, Volume 1: Building an Empire, 1846-1917 . University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8122-0762-0 , pp. 758 ff . ( google.cz [accessed March 1, 2020]).

- ^ A b Charles W. Raymond: The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad . In: The Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Gilbert H. Gilbert, Lucius I. Wightman, WL Saunders: The Subways and Tunnels of New York . John Wiley & Sons, New York 1912, p. 39 .

- ↑ a b c Davidson Gregg, Howard Alan, Jacobs Lonnie, Pintabona Robert, Zernich Brett: North American Tunneling: 2014 Proceedings . Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, 2014, ISBN 978-0-87335-400-4 , pp. 139–150 ( google.cz [accessed February 29, 2020]).

- ↑ $ 100,000,000 in 1910 → 2020. In: Inflation Calculator. Retrieved March 3, 2020 .

- ↑ HNTB (Ed.): Structural Assessment of the Amtrak Under River Tunnels in NYC Inundated by Super Storm Sandy . September 18, 2014, p. 2 ( tunneltalk.com [PDF]).

- ^ The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159. pp. 425-426

- ^ The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159, p. 435

- ^ Vincent Tirolo Jr .: Tunneling Under the Hudson and East Rivers in the Early 1900s: Risk Identification and Management Lessons That Are Still Useful Today . In: Society of Mining (Ed.): North American Tunneling: 2014 Proceedings . 2014, p. 139–150 ( google.cz ).

- ^ The East River Division . Paper No. 1152. Plate 13. Wikimedia Commons

- ^ The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159, p. 435

- ^ The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159, p. 433

- ^ The East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1159. p. 451

- ^ A b George C. Clarke: The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Long Island Approaches to the East River Tunnels. Paper No. 1162 . In: American Society of Civil Engineers (Ed.): Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers . tape 69 , October 1910, p. 91-131 .

- ^ The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The North River Tunnels . In: Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers . tape LXVIII , no. 1155 . The Society, September 1910, pp. 236 ( wikimedia.org [accessed February 29, 2020]).

- ^ Pennsylvania Railroad (Ed.): Pennsylvania Railroad System's exhibit at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition . Philadelphia 1909, p. 9 ( oclc.org ).

- ^ George Gibbs: The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Station construction, road, track, yard equipment, electric traction, and locomotives. Paper No. 1165 . In: American Society of Civil Engineers (Ed.): Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers . tape 69 , September 1910, p. 279 .