Scone (Perth and Kinross)

|

Scone Scottish Gaelic Sgàin |

||

|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 56 ° 26 ′ N , 3 ° 24 ′ W | |

|

|

||

| administration | ||

| Post town | PERTH | |

| ZIP code section | PH2 | |

| prefix | 01738 | |

| Part of the country | Scotland | |

| Council area | Perth and Kinross | |

| British Parliament | Perth and North Perthshire | |

| Scottish Parliament | Perthshire North | |

Scone [ skuːn ] ( Gaelic: Sgàin ; medieval: Scoine ) is a village in Perth and Kinross , Scotland .

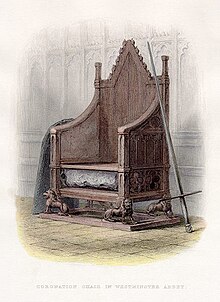

Old Scone was the historic center of the Pictish Kingdom from the 8th century and later the United Kingdom of Alba and the coronation site of the Scottish kings until the 17th century . It is likely that King Kenneth MacAlpin brought the Scone Stone here from Ireland in the 9th century . In 1297 he was kidnapped by Edward I of England as spoils of war to Westminster Abbey . Until then, all Scottish and then until 1953 all English and British kings were crowned in Scone . But since 1996 it has been kept at Edinburgh Castle .

Around the old Pictish coronation hill Moot Hill , the important Scone Abbey with a palace as a royal residence, as well as the two burghs (free cities) Scone and 1.5 km downstream Perth were built in the 12th century . In the later Middle Ages, scone lost its importance. In 2007 archaeologists determined the exact location of "Scone Abbey", which was looted and burned in 1559 at the height of the Reformation . The discovery of the outline of the "lost abbey" founded in 1114 exceeded all expectations.

New Scone is just over a kilometer east of Old Scone. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Earl of Mansfield built a new castle on the site of the old abbey, today's Scone Palace . To make room for the castle park, he moved the entire village of Scone, including houses, shops, church and all residents, about one kilometer east of the castle and the River Tay . The place New Scone is officially called Scone again since 1997 . In 2001 it had a total of 4430 inhabitants.

history

The small Bronze Age stone circle of Sandy Road (also called Greystanes) is located in New Scone.

Pictish royal center (8th century - 841)

Scone's Moot Hill has long been a religious center. But in the 8th century Scone also became the center of the Pictish kingdom and possibly the coronation site of its kings.

The epithet Hill of Credulity or Hill of Belief for the Moot Hill of Scone was probably coined at the event here in the year 710, when

"Nechtan, King of the Picts, ... revoked the mistake that he and his country had made in observing the Easter date and submitted, together with his people, to celebrate the Catholic date of our Lord's resurrection."

It is also quite possible that the names Scoine sciath-airde , "Scone of the high shields", and Scoine sciath-bhinne , "Scone of the loud shields", from Gaelic poetry in the Middle Ages, had their roots as Scone 728 for an important scene Battle in Pictish history.

The Banquet of Scone, the betrayal of Kenneth MacAlpin (841–858)

In a battle with the Vikings , 839 Uen, the last king of the independent Pictish kingdom, died together with his brother Bran and the Pictish army in innumerable numbers. Uen's death was followed by a power vacuum in the Pictish kingdom, which had also controlled Dalriada since the 8th century . At least four potential heirs to the throne vied for the Pictish throne. According to legend, Kenneth MacAlpin , the last king of Dalriada, invited the Pictish heir to the throne Drest and the few remaining Pictish nobles to Scone in this situation in 841 to discuss the independence of Dalriada. There was a lot of drinking here. However, the Scots of Dalriada came secretly armed to Scone and killed all the Pictish nobles.

Heyday in the early Scottish Kingdom (843–1296)

The fact is that Kenneth MacAlpin had defeated all Pictish adversaries by 848. MacAlpin has been the 1st King of the United Scotland (Alba) since his coronation on the Stone of Scone in 843. Kenneth may have brought this stone to Scone from Iona or Ireland around 840 . In any case, from then on, all Scottish kings were crowned here until the end of the 13th century. The stone was set up outdoors on the historic Moot Hill, on which the Pictish kings had also been crowned.

Scone thereby gained in importance and became the center of the Kingdom of Alba. The medieval Gaelic poetry describes Scone as Scoine sciath-airde, ("Scone of the high shields") and Scoine sciath-bhinne ("Scone of the loud shields"). Scotland itself was often called the "Kingdom of Scone", Righe Sgoinde . At this early stage, then, Scone was the closest thing to a capital of the Kingdom of Scotland.

The pagan coronation rites with the Stone of Scone on the archaic Moot Hill in the old Irish style were notorious among the aspiring Anglo-Normans in the 12th century. Under French influence, Alexander I of Scotland (ruled 1107–1124) tried to transform Scone into a more convincing royal center: a village ( burgh ) was established. In 1124 Alexander promised in a letter to "all merchants of England" ( omnibus mercatoribus Angliae ) that this protection would be granted if they brought goods across the sea to Scone. However, Scone was not on a navigable part of the River Tay . This possibility was only available 1.5 km downstream near Perth (from Aber-Tha, 'mouth of the Tay'). That is why the new burgh (free city) Perth was founded there under David I. Under William I. the Lion , Perth was given the title of royal burgh . King Alexander I also founded an Augustinian monastery in Scone between 1114 and 1122 . In 1163 or 1164, during the reign of Malcolm IV , the monastery was elevated to an abbey and an abbey church, Scone Abbey. Located right next to the Coronation Hill, the abbey fulfilled important functions in the kingdom. The imperial insignia, the crown, the cross of St. Margaret ("Black rood of St. Margaret") and the coronation stone were kept in the church. Furthermore, the abbey served as a royal residence or palace when the kings were present.

When the Scottish kings themselves became more French than Gaelic in the further 12th century, the prominent role of scones came under threat. Walter of Coventry reported at the time of Williams I of Scotland:

“The modern kings of Scotland understand themselves better than French in race, manners, language and culture. They only employ French in their household and their entourage and have reduced the Scots to mere service workers. "

If exaggerated, there was a great deal of truth in it. When the normanized David I of Scotland came to Scone for his coronation in the summer of 1124, he initially refused to take part in the traditional ceremony on the archaic Moot Hill and was only persuaded by the bishops to take part with great difficulty. Ailred of Rievaulx , friend and member of the royal court, reports about it: David “so abhorred those acts of homage which are offered by the Scottish nation in the manner of their fathers upon the recent promotion of their kings, that he was with difficulty compelled by the bishops to receive them ". This inevitably had an impact on the importance of scones as a ritual and cultural center.

In the 13th century the main royal residence was relocated to Perth, later to Dunfermline and finally to Edinburgh . However, the coronation ceremony on the stone of Scone was essentially maintained through the 13th century. The kings continued to use Scone as a residence until the late Middle Ages and Scottish parliaments met here regularly.

Change in the Scottish Wars of Independence (1296-1350)

In 1296 King Edward I of England brought all of Scotland under his control. He stole the crown, the holy cross Black rood of Margaret and the stone of Scone from Scone Abbey and brought them to Westminster . The stone of Scone was set on the English throne. Since then, all English and British kings have been crowned seated over it. Even without the stone, the Scottish kings were still crowned in Scone until the end of the Scottish Kingdom.

At the end of May 1297, William Wallace intervened in the burgeoning first Scottish War of Independence against England in Scone by attacking the English justiciary William de Ormesby with a small rebel army from the hills, who held court in Scone over those who swore no allegiance to Edward . Ormesby narrowly escaped and galloped to Edinburgh with the news of the rebellion. In the same war, Scone Abbey came under heavy attacks.

Of all the coronations in Scone, that of Robert the Bruce on March 25, 1306 was one of the most famous. It was also arguably the first since Kenneth MacAlpins over 450 years earlier to take place without the Stone of Scone. Only in the peace treaty of 1328 between Robert the Bruce and Edward III. England recognized the independence of Scotland again. The contract also provided for the return of the crown insignia stolen in 1296. While the holy cross of St. Margaret actually found its way back to Scone, the Stone of Scone stayed in Westminster Abbey for another 650 years.

Descent in the later Scottish Kingdom (1350–1701)

Even if Scone was retained as the coronation site, it lost its role as “capital” in the later Middle Ages. Scone Abbey became a pilgrimage center for St. Fergus , whose head it kept as a relic, it maintained traditional festivals and an excellent reputation for excellent music. In the 16th century, the Scottish Reformation ended the importance of all monasteries in Scotland, and in June 1559 the abbey was attacked and burned by followers of the Reformation from Dundee . Some monks continued to run the abbey, but by the end of the century monastic life had disappeared. In 1581 Scone came to the area of the newly created County Gowrie . In 1606 the county was bestowed on David Murray, who received the new title Lord Scone, which was upgraded to Viscount Stormont in 1621. The abbey and the palace remained in a habitable condition, as the Viscounts apparently carried out some restorations and continued to keep their seat there. In 1624 a new parish church was built on Moot Hill, of which only one nave remains today. Scone also played host to important guests such as King Charles II of Scotland and England when he was crowned the last king in Scone in 1651. In 1803 the family (now Earls of Mansfield) commissioned the English architect William Atkinson to build a new palace, Scone Palace.

New Scone (1805-today)

To make room for the palace gardens around the new Scone Palace, the old village of Scone was destroyed in 1805 and its residents, including shops and churches, were relocated to a new location planned on the drawing board, which was originally called New Scone. For the move, the two churches in the village were dismantled stone by stone and rebuilt 2 km further east in New Scone.

There is not much of Old Scone to be seen in the park of Scone Palace today except for the mercat cross (market cross) , the old cemetery, the archway from the 16th century as an impressive entrance into the City of Scone and of course the ancient Moot Hill, on which the kings were crowned, including a preserved part of the parish church from 1624.

Since 1997, New Scone is officially called Scone again for short. In 2001 Scone had 4,430 inhabitants according to the Census of Scotland.

useful information

The scone pastry is pronounced as [ skɒn ] or [ skəʊn ], while the place is pronounced as [ skuːn ]. Both terms have no common background.

Scone is mentioned in William Shakespeare's drama Macbeth (2nd act, scene 4) from 1607 as Macbeth's coronation site . In addition, it is the very last word of the tragedy: “So, thanks to all at one and to each one / Whom we invite to see us crown'd at Scone.” (“You all get thanks and reward, / And now to top it off, I invite you to Scone. ")

The botanist David Douglas , after whom the Douglas fir is named, was born in Old Scone in 1799. As a 6-year-old, he witnessed the relocation of Scone. At the age of 11 he was already working as a gardener in the newly created Scone Palace. He died in Hawaii at the age of 35 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Information in the Gazetteer for Scotland

- ↑ Michael Lynch : Scotland, A New History. 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Bede (673-735), from Medieval Sourcebook, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Book V , Chapter XXI

- ↑ Michael Lynch: Scotland, A New History , 1991, p. 42.

- ↑ John Preeble: The lion in the north , 1971, p 20

- ↑ Described in the medieval Profecy of Berchan . See: Alan Orr Anderson : Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500-1286 . Edinburgh, 1922, Volume 1, pp. Xxxiv-xxxv.

- ↑ The name Alba was actually only used in the 10th century for MacAlpin's successors.

- ^ William F. Skene: Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots and Other Early Memorials of Scottish History . Edinburgh 1867, pp. 84, 97.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 21.

- ^ Eg John J. O'Meara (Ed.): Gerald of Wales: The History and Topography of Ireland . London 1951, p. 110.

- ^ Archibald Lawrie: Early Scottish Charters Prior to AD 1153 . Glasgow 1905 no. Xlviii, p. 43.

- ↑ RM Spearman: The Medieval Townscape of Perth . In Michael Lynch, Michael Spearman & Geoffrey Stell (Eds.): The Medieval Scottish Town . Edinburgh 1988, p. 47; Lawrie: Early Scottish Charters, p. 296.

- ↑ Perth royal burgh charter ( Memento of the original from January 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , bestowed by King William the Lion in 1210, Archives of Perth & Kinross Council.

- ^ Ian B. Cowan, David E. Easson: Medieval Religious Houses: Scotland With an Appendix on the Houses in the Isle of Man . 2nd ed., London 1976, pp. 97-98.

- ^ W. Stubbs (Ed.): Memoriale Fratris Walteri de Coventria (= Rolls Series 58). P. Ii. 206.

- ↑ AO Anderson: Scottish Annals, p. 232. It should be noted that Ailred was interested in portraying David as a good Anglo-Norman. He was careful not to subject David to anti-Scottish prejudices that would have destabilized his image in the Anglo-Norman world.

- ↑ John Bannerman: The Kings Poet . In: The Scottish Historical Review . Volume 58, (1989), pp. 120-149.

- ↑ James II of Scotland was not crowned in Scone, but in Holyrood Abbey . However, he was still a child and political issues made the Scone ceremony too dangerous. Also his son James III. who also succeeded him as a child, was apparently not crowned in scone either. However, these two coronations only broke the old custom, which was revived by James IV .

- ^ John Prebble: The lion in the north . England 1971, p. 78.

- ^ Richard Fawcett: The Buildings of Scone Abbey . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze, Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 170-172.

- ^ Richard Fawcett: The Buildings of Scone Abbey . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze, Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 172-174.

- ↑ Scone New Church Family History ( Memento of the original from January 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ http://www.geo.ed.ac.uk/scotgaz/towns/townfirst154.html

literature

- GWS Barrow (Ed.): The Acts of Malcolm IV King of Scots 1153-1165, Together with Scottish Royal Acts Prior to 1153 not included in Sir Archibald Lawrie's "Early Scottish Charters" . Edinburgh 1960. ( Regesta Regum Scottorum Volume i).

- GWS Barrow: The Removal of the Stone and Attempts at Recovery, to 1328 . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003.

- DA Binchy: Fair of Tailtiu and the Feast of Tara . In: Ériu . Volume 18 (1958), pp. 113-138.

- Dauvit Broun: Origins of the Stone of Scone as a National Icon . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon , (Edinburgh, 2003), pp. 183-197.

- Thomas Owen Clancy: King-Making and Images of Kingship in Medieval Gaelic Literature . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 85-105.

- Ian B. Cowan & David E. Easson: Medieval Religious Houses: Scotland With an Appendix on the Houses in the Isle of Man . 2nd ed., London 1976, pp. 97-8.

- AAM Duncan: Before Coronation: Making a King at Scone in the 13th century . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 139-67.

- Richard Fawcett: The Buildings of Scone Abbey . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 169-180.

- Elizabeth FitzPatrick: Leaca and Gaelic Inauguration Ritual in Medieval Ireland . In: Richard Welander, David J. Breeze and Thomas Owen Clancy (Eds.): The Stone of Destiny: Artefact and Icon . Edinburgh 2003, pp. 107-121.

- Sir Archibald Lawrie: Early Scottish Charters Prior to AD 1153 . Glasgow 1905.

- Peter GB McNeill, Hector L. MacQueen (Eds.): Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 . Edinburgh 1996.

- O'Meara, John J. (Ed.): Gerald of Wales: The History and Topography of Ireland . London 1951.

- William F. Skene (Ed.): Chronicles of the Picts, Chronicles of the Scots and Other Early Memorials of Scottish History . Edinburgh 1867.

- William F. Skene: The Coronation Stone . In: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland . Volume 8 (1868-70), pp. 68-99.

- RM Spearman: The Medieval Townscape of Perth . In: Michael Lynch, Michael Spearman & Geoffrey Stell (Eds.): The Medieval Scottish Town . Edinburgh 1988, pp. 42-59.

Web links

- German-language links

- The history of the Stone of Scone on www.macroy.de

- English-language links from local institutions

- Scone Palace

- Scone New Church Family History

- Robert Douglas Memorial School: Scone, our village

- More links in English