Period furniture

The term period furniture describes a piece of furniture in which an earlier furniture style was reproduced at the time of manufacture. Accordingly, the definition of period furniture in the Duden is : "piece of furniture made as an imitation of an earlier style". The word explanation from the DWDS [word information system for the German language] adds the temporal dimension: "Furniture from the 19th or 20th century that was made in an earlier art style [sic]".

Style periods are usually only given a designation in their last phase or after the end, which is then used. The term “period furniture” only became known at the beginning of the 20th century and has been used since then to differentiate it from other types of furniture. The DWDS diagram of the word frequency shows that the word “period furniture” did not appear until after 1900 - around the time of the First World War - and then spread until it reached its peak around 1980 and then became less common.

Period furniture in the first main period 1830/40 to 1910/20

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Biedermeier , which in the final phase of classicism became the epitome of bourgeois living culture, is considered to be the penultimate independent furniture style. In contrast, the subsequent historicism in architecture and interior design fell back on older historical styles. The period furniture took its course.

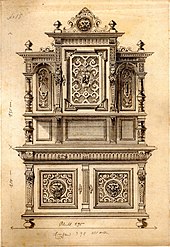

In Rainer Haaff's Historicism Lexicon, splendid stylish furniture / historicism in Germany and Central Europe , it says: "'Historicism' is an art-stylistic umbrella term for several neo-styles that follow one another at short notice or that took place simultaneously in the period from 1830/40 to 1910/20" . During this period, the preferred furniture was made in one of the historicist styles: neo-Gothic , second rococo , Louis-Philippe , neo-renaissance , third rococo , third baroque or in the Wilhelminian style , which represents "a German style modification of the neo-renaissance" from 1880 to 1915.

The traditionally handcrafted carpentry workshops adhered conscientiously to the models of the respective style period. The artisans often proved themselves to be great masters in the faithful replica. Rainer Haaff goes on to say: “Much of the period furniture of historicism is of a copyistic nature and is therefore strictly committed to the respective style model. Others, on the other hand, include a corresponding style orientation, but at the same time allow contemporary expediency, economic reduction and artistic creativity to be expressed. "

In addition to the period furniture of historicism, simple furniture without ornaments was also created. As functional furniture, for example for workspaces or workers' quarters, they were only valued little - especially because they were produced as cheap "industrial furniture" by the workshops that switched their businesses to series production as a result of the industrial revolution . In the upper ranking, however, Art Nouveau drew attention to itself in the years around 1890 to 1910 . The creative products with decoratively curved lines and floral ornaments , however, by no means met with broad approval from consumers.

At the beginning of the 20th century - still in the German Empire - developments in the furniture sector were still tied to the ideas of the rich bourgeoisie: Renaissance , Rococo and Gothic remained in fashion. The lavish use of decorative forms documented the pompous taste of the time. In the years before the First World War, the “period furniture” category was predominantly present.

Period furniture in the second main period from 1910/20 to 1980/90

After the First World War, the movement continued with the founding of the Bauhaus , which finally exerted a fundamental influence worldwide in all areas of applied art. The new design propagated by young architects, artists and artisans with the consistent focus on practicality and turning away from all unnecessary ornamentation was still rejected by the general public as puritanic sobriety in the design of personal living areas. The innovative style of Art Deco in connection with Art Nouveau also remained only a marginal phenomenon.

In view of the general taste uncertainty among manufacturers and consumers, the search for appealing shapes has repeatedly led to a reflection on tradition. The buyers preferred familiar furniture that promised the coveted cozy living atmosphere. So the period furniture kept the upper hand - and long after the Second World War.

At the time of the currency reform after the end of the war, the furniture industry in West Germany continued the development in the pre-war period. The pent-up demand in all areas of the furnishing industry caused a strong expansion of the operating capacities in a few years. The relationship between “style” and “modern” had not changed at first. Dirk Fischer wrote in his master's thesis The East Westphalian-Lippe Furniture Industry between 1945–1975 : “Furniture in baroque shapes was offered at the first Cologne furniture fairs in the high and medium price range ... Furniture in extremely modern and simple shapes, however, was offered in the first few years Hardly exhibited in Cologne, as there was hardly any interest in them from the consumer side. "

An opinion poll carried out by the Allensbach Institute for Demoscopy in July 1954, using pictures of various furnishing styles, showed that 60% of the West German respondents preferred the bourgeois line [with curved shapes] of the thirties and only almost a third preferred the moderately modern room furnishings .

The publication: 10 Years of Furniture in the Federal Territory of the Ifo Institute for Economic Research in 1957 presents furniture sales as follows: “The 1956 furniture fair clearly showed that the taste of West German furniture consumers seems to have established itself in the meantime, as today either furniture from the moderate modern line or pure period furniture are preferred. The so-called 'modern line' is only bought by certain classes and is still rejected by the majority of the masses. "

For the end of the 1960s, in the article New furniture in old style in the magazine Heimat from September 1967, the proportion of period furniture in the Federal Republic of Germany is still around 40%. The spread of period furniture only slowly weakened from its peak after the period of historicism over the decades until 1980/90.

The variety of period furniture - stylish or modified, high or inferior, expensive or cheap - was coveted by all walks of life, regardless of the position, wealth or education of the furniture consumer.

Development of the period furniture characteristics in the second period

In the 20th century, period furniture continued to deviate from its models in design and execution because new factors influenced the design of period furniture.

Influencing factor 1 - Changed spatial conditions, new accommodation requirements: New types of furniture

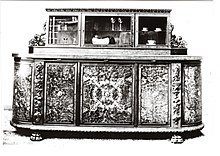

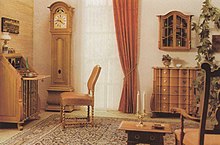

A striking change was looming in the proportions of the furniture types: the traditional cupboard furniture showed an emphasis on the vertical due to the conventionally high rooms, now the horizontal became more important. The new contemporary apartments were lower and smaller, they were also centrally heated. Practicality and convenience determined the trend, for contemporary furnishings - whether stylish or modern - more comfortable seating furniture and tables as well as more diverse box furniture were created, which were suitable for accommodating the constantly growing household items, books and new technical devices.

Typical for the 1950s are the add-on furniture with standardized divisions to choose from: open shelves, glass door or paneled door compartments, drawers, bar compartments, TV compartments, etc. The half-height add-on basic types could be lined up as required - even across corners. The further development led to the wall units , with which from the beginning of the 1960s it was possible to equip every room from wall-to-wall and from floor-to-ceiling. These programs - like the tall cupboards in the bedroom - made it possible to adapt to difficult room situations and to meet special requests with relatively little effort.

In the style area, the details of the respective style direction in the front and body parts were conspicuously reproduced. However, the external shape of the new style wardrobe types expressed a fundamentally modern development - without any model in the past.

Influencing factor 2 - sales through furniture dealers and series production: Reduction of the variety of offers, typification and standardization of furniture

Traditionally, the master carpenter - in one-man operation or in furniture workshops - had determined the design of the furniture in direct contact with the customer. Samples or drawings were used for communication . The exclusive one-off piece through to the comprehensive custom-made interior was made step by step by qualified craftsmen according to the wishes of the customers.

After the First World War, the furniture shop had predominantly taken on the mediating role between manufacturer and buyer. Style furniture stores emerged in larger cities, often with the help of employed draftsmen and interior designers, to offer discerning customers individual advice. In principle, ready-made goods were sold in the trade, which were represented by illustrated sales documents such as catalogs with price lists. While before 1900 most carpenters generally made all types of furniture, the furniture factories had now returned to their specialty and only supplied living room or bedroom furniture, kitchens, box furniture or seating furniture. This concentration on certain types of furniture also led to standardization in the style area, the furniture dimensions resulted from the modular construction . All models belonging to a group (“set”) had the same characteristics, such as profiles, curves or ornaments.

With the typing of the period furniture, a further deviation in form and design from the original furniture of the style to be reproduced was made.

Influence factor 3 - New materials and mechanization of production: Large formal deviations from the historical model

Modern construction made of fully veneered wood material (plywood or chipboard), outside with double frame, middle area with applied curved profiles and carvings to represent a filling.

Advantage: dimensional stability when the humidity changes

Modern construction made of fully veneered wood-based material (plywood or chipboard) with applied curly profiles and carvings to suggest the stylish image of the frame and paneling.

Advantage: dimensional stability when the humidity changes

Authentic construction made of frame and filling - carvings and profiles cut from solid wood.

Note: An upright crack in the panel carving at the top right and open joints when the frame parts were joined were caused by the wood “working” due to its hygroscopic properties .

The most profound deviation from the historicist model was caused by the use of new materials and the use of advanced manufacturing technology.

When the plywood board came up around 1900 , the less visible wooden surfaces, which are professionally made of solid fillings with joins, such as rear walls, drawer bottoms, etc., were replaced by dimensionally stable plywood. The thicker plywood board , the so-called blockboard , soon followed , and then around 1950 the chipboard with the best dimensional stability. All flat furniture parts such as panels, sides, shelves, etc. were soon cut from the new material, provided with solid pre-glued and veneered .

With new special machines, well-tried carpenter constructions such as frame / filling, slot / tenon, tongue / groove, prongs / dovetail and the typical style shapes such as profiles and curves can be manufactured precisely and efficiently depending on the batch size. Particularly striking were the carving machines, which largely replaced the elaborate carving by hand. Since machine tools such as milling cutters and drills machine the wood by rotation, sharp inside corners and edges cannot be machined. In the case of high-quality period furniture, the inner corners and edges were re-engraved by hand, and the pre-drilled carvings were given the final fine cut by the skilled hand of a wood sculptor . In the case of cheap period furniture, many details were "rounded" so that reworking was not necessary.

As early as the 1920s, people started to merely suggest the frame infill construction required for historical furniture doors by gluing profiles and ornaments onto the veneered industrial panels. The edges of the furniture front parts were also glued with solid wood so that the internal structure did not appear. An "antique" surface treatment with color gradients and patina effects compensated for differences between solid wood and veneer . The furniture fronts with doors, flaps and drawers could be manufactured uniformly in large numbers. Typical solid wood features such as knots and irregular grain were undesirable.

The permanent deformation of solid wood and plywood under heat, steam and pressure also influenced the design of period furniture. In combination with new polishing materials and techniques, large curved surfaces such as wardrobe doors could be produced in large quantities.

The range of period furniture and the styles "Old German" and "Chippendale"

While in the modern area new types of furniture were developed independently of models, in the style area people were less willing to experiment because of the required style. Nevertheless, the new industrial manufacturing processes led to typical style furniture directions, which achieved a high level of awareness among furniture buyers.

The selection of period furniture was extremely varied. The range was led by expensive offers that met the high demands of buyers in terms of quality and aesthetic design, which was reflected in the implementation of historical style elements. There were also the modest and inexpensive versions. Many period furniture manufacturers have developed their own style programs and have represented their " brand " for decades.

With the wide range of period furniture, two styles had gained outstanding importance on the furniture market and had become the epitome of period furniture.

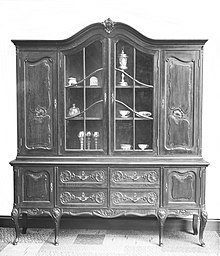

"Old German furniture" are straight types of furniture in a vague reference to Gothic or Renaissance - in stylized forming by edge profiles, Kannelierfräsungen , wood used ornament strips, cassette type combinations for the " false edge " on surfaces, such as sides, doors, flaps and drawers, also with turned parts such as Rosettes as surface decoration, legs and feet. Glazed doors usually show tinted "antique glass" with lead or brass surrounds. Walnut and oak were popular as types of wood, especially in the 1960s and 70s, the "rustic oak" design with emphasis on the distinctive wood structure was very popular.

“Chippendale” (the famous English cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale designed and marketed magnificent furniture in the 18th century) is furniture whose shape is reminiscent of Baroque or Rococo . The models show the typical profiles and curves, especially the curved leg shape. Frequently was Sonnengeflecht used for laminating sound equipment. Many “Chippendale” furniture showed carvings as ornaments glued on. Fine-pored types of wood such as beech , alder , maple and others were processed, real walnut only for expensive offers. A typical color is "antique walnut", which changes to emphasize the shape. In the 1960s and 70s, with the further development of wood varnishes, the sanding varnish version with fine nuances was in great demand, often with gilding of the decorative shapes.

In cooperation with furniture retailers, the German Style Furniture Working Group (see following section) carried out market surveys on period furniture in 1960 and 1968.

When asked: "If you buy period furniture, which style would you prefer?"

, The following answers came up for 1960/1968:

a) Old German forms 18% / 38%, b) Baroque forms ("Chippendale") 22% / 22%,

c) Biedermeier 4% / 6%, d) Renaissance 3% / 4%,

e) Classicism 1% / 3%, f) no specific opinion 52% / 27%.

The striking increase in the popularity of the old German forms from 18% to 38% within eight years from 1960 to 1968 points to the "rustic wave" that became apparent in buyers' tastes from the mid-1960s and prompted the furniture industry to offer corresponding offers.

Style furniture after the Second World War in West Germany and foundation of the "German Style Furniture Working Group"

After the Second World War, almost every company in the West German furniture industry first developed its pre-war programs, which had already been introduced in the furniture trade.

With the consolidation of industrial furniture production in the mid-1950s, increasing competition in various sectors of the furniture industry became noticeable. In the “Style” area, the increased advertising for contemporary “modern furniture” - as well as the increased criticism of cultural workers and opinion leaders of the Germans' preference for period furniture - was perceived as disturbing. Living magazines such as Architecture and Cultivated Living , Beautiful Living and Home published articles such as “Controversy about period furniture”, “Why we still make period furniture and why period furniture is bought” or “New furniture in the old style”.

In order to counteract this development , seven period furniture manufacturers came together in autumn 1958 on the initiative of Bartels-Werke GmbH, Langenberg , and founded the “German Style Furniture Working Group” (ADS). The statutes describe the purpose:

- to maintain and cultivate traditional styles in order to make them usable in furniture construction and interior design for today's living needs;

- to advertise good period furniture to consumers and specialist retailers, to arouse interest in good period furniture and to keep it alive in the long term.

In 1963 there were already sixteen, and in 1970 twenty-two well-known period furniture manufacturers who operated joint advertising.

The members saw themselves as a group of period furniture manufacturers who served the discerning clientele of style furniture stores and period furniture departments in newly established furniture stores; They also offered themselves as competent partners in the contract area for representative public and business facilities - such as hotels and restaurants. They were medium-sized companies with up to 500 employees who had either developed complete period furniture programs with all types of furniture for home furnishings, or they specialized in home furniture, bedrooms, tables, chairs or upholstered furniture and formed sales groups for the stylistic coordination of the models Sale, e.g. B. Quadriga style furniture (Georg Pollmann, Warburg - Franz Finkeldei, Steinheim - Ludwig Finkeldei, Nieheim - W. Wente & Sons, Eimbeckhausen ).

Some complete programs that had been established since the 1930s were viewed within the German Style Furniture Working Group as representative of high quality style furniture; for example the Spilker style furniture in Aachen-Liège Baroque , which the sculptor and furniture designer Anton Spilker had designed for his company in Steinheim . The ornamentation of the period furniture, which was adapted for contemporary use, was modeled on the relief carvings of the regional baroque variant of the 18th century.

The Busch style furniture factory in Kastorf had specialized in the processing of the native oak under the master carpenter Hans Busch. His style furniture in Dutch Baroque was in all parts - even back walls and curved wreath floors - made of solid material that was smoked and waxed appropriately.

The trademark "STIL" [gold medal for good style] was used as a mark of quality for good style and excellent quality on all advertising materials of the member companies, and every piece of furniture to be delivered received the corresponding label. Advertisements were regularly placed in the living magazines and specialist bodies, offering prospective customers brochures with furnishing examples, manufacturer references and detailed stylistic knowledge. In the three decades of its activity, the working group successfully sold countless illustrated books, which were reprinted every year. The period furniture buyers, who had already informed themselves, made preliminary decisions about the period furniture specialist shop - a clear advantage for the programs of the member companies compared to other period furniture offers.

A survey of the industry for the International Furniture Fair in Cologne shows the magnitude: "As early as 1970, the member companies of the German Style Furniture Working Group alone achieved sales of 150 million DM." This statement is followed by another overview: "The total sales of all German style furniture manufacturers was estimated at around half a billion DM in the same year. ”The term“ rustic wave ”is used here, which includes rustic furniture in all price ranges, genres and style periods.

The importance of period furniture is waning

After the furniture industry had experienced an uninterrupted upward trend for almost 25 years in the post-war period, a phase of stagnation was heralded in the early 1970s. Most of the furniture factories had significantly expanded their operating capacities; these could no longer be used to full capacity after the war-related “pent-up demand” for the durable products of the furnishing industry had become “replacement demand”. The entire industry - including the period furniture industry - struggled with the sales crisis.

The extensive advertising campaigns of the German Style Furniture Working Group had indeed promoted the general appreciation of style furniture and generated sales advantages for the members, but could not do anything against the fundamentally negative trend in the furnishing industry.

The situation was made even more difficult by the sharp rise in wage costs in the 1970s and 80s. An economic report by the specialist furniture market for the German furniture industry found, for example, that in 1974 average nominal growth of around 2% was offset by average price increases of 10%, so that there was a noticeable contraction in real terms. Similar negative reports kept appearing, and every company tried to find a solution that was right for them.

In addition to increased savings and rationalization measures, some furniture plants have been able to assert themselves through consistent market orientation with their own brand in the modern sector or nameless mass-produced goods. Above all, some large companies have survived by relocating production to low-cost countries and opening up new sales areas abroad.

Period furniture experienced an increased recession by the end of the 1970s at the latest. Company failures kept increasing. The wage-related costs for the richly designed furniture were generally higher because of the larger manual and mechanical work involved. The rising wages therefore resulted in disproportionate price increases.

An effort began to develop new period furniture programs with the help of business consultants and furniture designers in order to mobilize the group of buyers. New models were created as prototypes in a very short time . They ventured into previously little tried varieties of international art styles such as Régence , Empire and Directoire . But there had been a general change in taste; the younger generation was no longer interested in period furniture.

By 1990, almost all of the well-known German style furniture factories had disappeared from the furniture market - including respected family businesses, the origins of which went back to the founding years of the 19th century. The German Style Furniture Working Group had also disbanded. In addition, there have been general changes in consumer habits, according to which furniture (like other products) is often no longer purchased for a lifetime, but rather replaced when fashion changes; The high price of the period furniture due to its elaborate workmanship and the relatively expensive materials became even more of a disadvantage under this aspect.

As an exception, for example, the furniture company Trüggelmann from Bielefeld, founded in the 1930s, succeeded in bringing the rococo style design - individual pieces of furniture and complete fittings in a nuanced lacquer surface - through the recession alongside the modern bedroom line. By acquiring international project fitters, the Trüggelmann company now primarily serves customers abroad.

Time and again one has convinced in the advertising for the period furniture with the statement that it is absolutely timeless and does not depend on any fashion. In the real world, however, it has been shown that this statement had to be put into perspective. In 1936, the young budding master carpenter Bernward Spilker from the Anton Spilker art cabinet maker, Steinheim, wrote in his treatise “Can historical furniture styles be used in modern living spaces?”: “The period furniture is always 'beautiful' because it cannot 'become out of date' - that's what you say, and you always say it in times of uncertainty in terms of design and taste. But it's just not true. Rather, one indulges in a benevolent illusion when one believes that period furniture, being 'timeless', will not be affected by taste inflation. "

On the antiques market , the demand for period furniture is also currently low. It is true that higher prices are paid for particularly high-quality pieces from well-known manufacturers, but in most cases the commercial value of period furniture is in the lower range of the currently sharply reduced price spectrum. Items from newer production, for example from the last 40 years, are almost impossible to sell on the used goods market.

literature

- Duden, German Universal Dictionary (DUW) . 2nd edition 1989, p. 1470, ISBN 978-3-411-02176-5 .

- Rolf-Ulrich Kunze: Symbioses, rituals, routines: Technology as part of identity: Technology acceptance from the 1920s to 1960s . KIT Scientific Publishing, 2010, pp. 173-174, ISBN 978-3-86644-493-5 .

- Julius Posener: Articles and lectures 1931 - 1980 . Vieweg & Teubner, Wiesbaden 2012, p. 223 ff. ISBN 978-3-663-00115-7 .

- Barbara Hölscher: Lifestyles through advertising? On the sociology of lifestyle advertising. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1998, p. 49, ISBN 978-3-322-87309-5 .

- Joachim Petsch: Home and parlor: On the history of middle-class living . DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 978-3-7701-1759-8 .

Web links

- Michael Finger explains wood and wood techniques

- Stylistic terms presented by antiques dealer Andreas Winkler

- An online reference work on wood technology by Andreas Gronemeyer

- An online reference work on wood technology by Volker Scharfe

- "Living in a bungalow from the 1970s" by the DFG project portal everyday cultures in the Rhineland

- SPECTRUM, “period furniture” becomes antique The mirror. No. 9, 1982.

- ANTIQUES, Miraculous Multiplication The Mirror. No. 39, 1982.

- Homepage of the Furniture Museum Steinheim (Westphalia) with exhibits from the Steinheim (Westphalia) period furniture industry

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden | Period furniture | Spelling, meaning, definition. Retrieved July 21, 2018 .

- ↑ DWDS - style furniture. Retrieved July 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Rainer Haaff: Magnificent furniture / historicism in Germany and Central Europe . Kunst-Verlag-Haaff, Leopoldshafen 2012, ISBN 978-3-938701-05-8 , pp. 23 , lines 1-4 .

- ↑ Rainer Haaff: Founder and Art Nouveau / Furniture and living cultures in the German Empire. Kunst-Verlag-Haaff, Leopoldshafen 2014, ISBN 978-3-938701-06-5 , p. 36, lines 3-4.

- ↑ Rainer Haaff: Magnificent furniture / historicism in Germany and Central Europe. Kunst-Verlag-Haaff, Leopoldshafen 2012, ISBN 978-3-938701-05-8 , p. 23, lines 16-21.

- ↑ Christoph Laue: Gustav Kopka - The pioneer of furniture series production from Herford , In Willi Kulke / LWL-Industriemuseum (Hrgb.): In series / 150 years of furniture industry in Westphalia. 1st edition, April 2015 Klartext-Verlag, Essen 2015. ISBN 978-3-8375-1412-4 , pp. 61–70.

- ^ Adolf G. Schneck: From the decorative element . In: New furniture from Art Nouveau to today . F. Bruckmann KG, Munich 1962, p. 9 .

- ^ Günter Schade: Neorenaissance and Gründerzeit . In: German furniture from seven centuries . Lambert Schneider Verlag, Heidelberg 1966, p. 89-90 .

- ^ Günter Schade: New attempts in the training workshops . In: German furniture from seven centuries . Lambert Schneider Verlag, Heidelberg 1966, p. 97 .

- ↑ Wolf Uecker: Art Deco / The Art of the Twenties . In: Heyne antique books . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-453-41115-3 , p. 92-123 .

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: 7.1.3. The traditional forms of furniture - building on the tried and tested . In: The East Westphalian-Lippe furniture industry between 1945 and 1975 . [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 129-132 .

- ↑ Manfred Sack: The German living room . Verlag CJ Bucher, Lucerne and Frankfurt / M 1980, ISBN 3-7658-0351-0 , p. 7-19 .

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: 7.1.3. The traditional forms of furniture - building on the tried and tested . In: The East Westphalian-Lippe furniture industry between 1945 and 1975 . [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 130 .

- ^ Roland Schroeder, Sosthenes Prokoph: 10 years of furniture in Germany . In: Series of publications by the IFO Institute for Economic Research No. 29 . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin / Munich 1957, p. 66-67 .

- ^ Roland Schroeder, Sosthenes Prokoph: 10 years of furniture in Germany. In: Series of publications by the IFO Institute for Economic Research No. 29. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin / Munich 1957, p. 65.

- ↑ a b New furniture in the old style . In: home / apartment house and garden . Jahreszeiten-Verlag GmbH, Hamburg September 1967, p. 20-29 .

- ↑ Herlinde Koelbl, Manfred Sack: The German living room. Illustrated part p. 21–133, text by Manfred Sack p. 7–19, article by Alexander Mitscherling p. 135–143. Publishing house CJ Bucher, Lucerne and Frankfurt / M. 1980, ISBN 3-7658-0351-0

- ↑ R. Bermpohl, H. Winkelmann: The question of the furniture style . In: Das Tischlerbuch / A textbook and reference book for the entire construction and furniture joinery with 1620 illustrations, ... 7th supplemented edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Gütersloh 1956, p. 243 .

- ↑ Edmund Meier-Oberist: cultural history of living in the western area . Ferdinand Holzmann Verlag, Hamburg 1956, p. 313 .

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: 7.1.2. The add-on furniture . In: The furniture industry in East Westphalia-Lippe between 1945 and 1975. [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 128-129 .

- ^ Günter Schade: The development after 1945 . In: German furniture from seven centuries. Lambert Schneider Verlag, Heidelberg 1966, p. 99 .

- ^ Peter HG Linsmayer: The furniture trade . In: Gotschy - Hobohm (Ed.): Germany's furniture industry 1945-1970 / inventory, documentation and outlook . Verlag Matthias Ritthammer, Nuremberg 1971, p. 169 .

- ↑ a b Ulrich Schäfer: Furniture construction and design from the point of view of inexpensive production . In: Sigrun Brunsiek - Landesverband Lippe - Institute for Lippe Regional Studies (ed.): Lippische Möbelindustrie 1900–1960 . Exhibition catalog / exhibition October 1 - November 28, 1993. Detmold 1993, ISBN 3-9802787-2-7 , pp. 90-97 .

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: 1. Introduction . In: The East Westphalian-Lippe furniture industry between 1945 and 1975 . [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 5 .

- ↑ R. Bermpohl, H. Winkelmann: plywood, fiberboard, chipboard . In: Das Tischlerbuch / A textbook and reference book for the entire construction and furniture joinery with ... 7th supplemented edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Gütersloh 1956, p. 42-44 .

- ↑ Carving machine on YouTube

- ^ R. Bermpohl, H. Winkelmann: The woodworking machines . In: Das Tischlerbuch / A textbook and reference book for the entire construction and furniture joinery with 1620 illustrations, ... 7th supplemented edition. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, Gütersloh 1956, p. 205-240 .

- ↑ X. Patina, shading . In: Curt Blankenstein (Hrsg.): Holztechnisches Taschenbuch . 2nd revised edition. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1962, p. 604-605 .

- ↑ 2. Mold presses . In: Curt Blankenstein (Hrsg.): Holztechnisches Taschenbuch . 2nd revised edition. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1962, p. 370-371 .

- ↑ In the spotlight: period furniture country house furniture country furniture . In: Möbelmarkt / specialist magazine for the furniture industry . Edition 7/75. Verlag Matthias Ritthammer, D-85 Nuremberg 1 July 1975, p. 1357-1371 .

- ^ Fritz Weischer: Working group German style furniture . In: Gotschy - Hobohm (Ed.): Germany's furniture industry 1945-1970 / inventory, documentation and outlook . Verlag Matthias Ritthammer, Nuremberg 1971, p. 120 .

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: 7.3. The "rustic wave" - a new trend leads to individual living . In: The East Westphalian-Lippe furniture industry between 1945 and 1975 . [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 147-151 .

- ↑ Arno Voteler: furniture design . In: Gotschy - Hobohm (Ed.): Germany's furniture industry 1945-1970 / inventory, documentation and outlook . Verlag Matthias Ritthammer, Nuremberg 1971, p. 150 .

- ↑ Dispute over the period furniture . In: Architecture and cultivated living . No. 7 . Jahreszeitenverlag GmbH, Hamburg 1963, p. 96-99 .

- ↑ Georg Wolf: Why we still manufacture period furniture and why period furniture is bought. In: Beautiful living . Issue 11. Constanze-Verlag, Hamburg November 1963, p. 164-173 .

- ^ Fritz Weischer: Working group German style furniture . In: Gotschy - Hobohm (Ed.): Germany's furniture industry 1945-1970 / inventory, documentation and outlook . Verlag Matthias Ritthammer, Nuremberg 1971, p. 118 .

- ↑ Weischer advertising agency: 20 years of the German Style Furniture Working Group . Ed .: Working Group German Style Furniture. Printing: Ritthammer-Druck KG GmbH & Co., Nuremberg 1978.

- ↑ Delf-P. Möller: Living in style . Ed .: Working Group German Style Furniture. 1st edition 1981. Printed by: H. Bösmann GmbH, Detmold 1981.

- ↑ Dirk Fischer: The "rustic wave" - a new trend leads to individual living . In: The East Westphalian-Lippe furniture industry between 1945 and 1975 . [Master's thesis] Bielefeld University / Department of History. Bielefeld August 2, 1996, p. 148 .

- ↑ Manfred Neumann: Development of the furniture industry in OWL 1970–2010 / economic crises, structural change and new markets . In: Willi Kulke / LWL-Industriemuseum (Hrsg.): In series / 150 years of furniture industry in Westphalia . 1st edition, April 2015. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8375-1412-4 , pp. 143-154 .

- ^ Siegfried Hobohm: The German Furniture Industry '74 . In: Möbelmarkt / specialist magazine for the furniture industry. 7/75 Verlag Ritthammer, Nuremberg, July 1975, pp. 1406-07.

- ↑ Alexandra Bloch Pfister: Reasons for the crisis and decline of the furniture industry in Steinheim . In: Friends of the Steinheim Furniture Museum (ed.): From Aachen-Lüttich to Eastern Europe . Storytelling café in the Möbelmuseum Steinheim on May 5, 2018. Print: Rainbowprint, Zellingen-Retzbach 2018, p. 9-10 .

- ↑ Alexandra Bloch Pfister: The competition prevails . In: Friends of the Steinheim Furniture Museum (ed.): From Aachen-Lüttich to Eastern Europe. Storytelling café in the Möbelmuseum Steinheim on May 5, 2018. Print: Rainbowprint, Zellingen-Retzbach 2018, p. 11 .

- ↑ Bernward Spilker: Can historical furniture styles be used in modern living spaces? Archive of Anton Spilker, Steinheim / Westphalia March 29, 1936, p. 14 .

- ↑ https://www.augsburger-allgemeine.de/kultur/Journal/Keine-Lust-mehr-auf-Altes-Preise-fuer-Antiquitaeten-sinken-id40563016.html