Sydney Observatory

| Sydney Observatory | |

|---|---|

|

Sydney Observatory added in 1874 |

|

| founding | 1858 |

| IAU code | 420 |

| Type | Observatory |

| Coordinates | 33 ° 51 '34.6 " S , 151 ° 12' 16.9" E |

| place | Sydney |

| operator | Government of New South Wales |

| Website | Sydney Observatory |

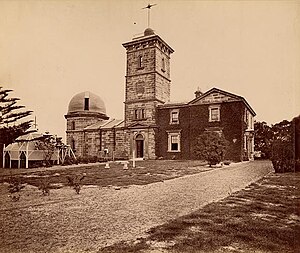

The Sydney Observatory (German Sydney Observatory ) is a listed weather station , astronomical observatory , event location, science museum and educational facility on Observatory Hill on Upper Fort Street in downtown Sydney , Millers Point, in the government district of Sydney New City South Wales , Australia . It was designed by William Weaver (plans) and Alexander Dawson (supervision) and built by Charles Bingemann & Ebenezer Dewar from 1857 to 1859. It is also known as The Sydney Observatory ; Observatory ; Fort Phillip ; Windmill Hill and Flagstaff Hill . It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on December 22, 2000 .

The site used to be a defensive fortress, a semaphore station , a time ball station , a weather station, an observatory and a windmill . The site developed from a fortress on Windmill Hill in the early 19th century to an observatory in the 19th century. It is now a museum where visitors can observe the stars and planets with a modern 40-centimeter Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope and a historic 29-centimeter refractory telescope from 1874, the oldest telescope in Australia.

description

The observatory is a two-story, Italian-style sandstone building . There are two telescopic domes on octagonal bases and a four-story tower for the time ball. The building, designed in 1858 by the colonial architect Alexander Dawson, consisted of a dome for the equatorial telescope , a room with long, narrow windows for the transit telescope , a calculation office and a residence for the astronomer . A west wing was added in 1877 with office and library space and a second dome for another telescope. Some of the earliest astronomical photos of the southern sky were taken at the observatory under the direction of Henry Chamberlain Russell . The observatory also took part in the compilation of the first atlas of the whole sky, the astrographic catalog . The part completed in Sydney lasted over 70 years from 1899 to 1971 and filled 53 volumes. The observatory once contained offices, instruments, a library and an astronomer residence. It is now a public observatory and a museum of astronomy and meteorology.

The building is built in the Florentine Renaissance style and the floors are divided by cornice , while articulated stones at the corners, eaves with stone brackets and beams at openings of the residence add to the fine stone masonry work. In a one-story wing in the north, a wooden balcony veranda was built with a stone balustrade built over it. The windows are twelve panes and the doors are six panels.

The observatory building is in good physical condition.

7.25 inch refractory telescope

At the Sydney Observatory there is a 7.25-inch refractor telescope on an equatorial mount, which was manufactured and installed by the German company G. & S. Merz between 1860 and 1861 .

history

Early use of the place

The site of the Sydney Observatory was a significant site in Sydney and has been renamed several times. It was known as Windmill Hill in the 1790s when the first windmill stood here. After 1804 it was referred to as Fort Phillip or Citadel Hill , referring to the construction of a citadel on the site to be used on the orders of Governor King in the event of a riot in Sydney. However, the citadel was never completed. This was sparked by an influx of "Death or Liberty" boys after the unsuccessful uprising in Ireland in 1798 , some of whom he believed were dubious and constantly aroused suspicion. Construction began, but the citadel was not completed until William Bligh was installed in the office. There was further discussion of a citadel during Lachlan Macquarie's time , but nothing happened more than a half-built powder magazine, Francis Greenway's first work after his appointment as civil architect in 1815.

In 1797, during the early European settlement of New South Wales, Australia, a windmill was built on the hill above the first settlement . Within ten years the condition of the windmill had deteriorated so much that it was unusable. The canvas sails were stolen, a storm damaged the machinery and the foundations gave way as early as 1800. The name Millers Point is a reminder of this early use.

1803 on the site under the direction of Governor Hunter , the Fort Philip built to the new settlement against a possible attack by the French and against rebellious convicts to defend. The fort never had to be used for such purposes. In 1825 the east wall of the fortress was converted into a signal station. Flags were used to send messages to ships in the port and to the signal station at the south head of the port .

The place was known as Flagstaff Hill during and after the Macquarie era . A flagpole had been erected on the site by 1811. Signaling with flags was a cumbersome process, and Commissioner Bigge advised Macquarie that it would be useful to set up a signaling station at South Head and Fort Phillip. The flags and signal station were used for signaling in a variety of combinations.

observatory

An early observatory was set up by William Dawes at Dawes Point at the foot of Observatory Hill in 1788 to watch the return of a comet predicted by Edmond Halley (not Halley's comet , but another) in 1790 . However, the observation was unsuccessful.

In 1848, the Mortimer Lewis Colony architect built a new signal station on the fortress wall on Windmill Hill. At the instigation of Governor William Denison , it was agreed seven years later to build a complete observatory next to the signal station. The first government appointed astronomer was William Scott , who was appointed in 1856. Work on the new observatory was completed in 1858.

The most important task of the observatory was to signal the time using the time ball tower. Every day at exactly 1:00 p.m., the time ball fell down on top of the tower to indicate the correct time to the town and port below. At the same time a cannon was fired at Dawes Point. The cannon was later moved to Fort Denison . The first time ball was dropped on June 5, 1858 at noon. Soon after, the time ball drop was postponed to 1:00 p.m. The time ball is still dropped daily at 1:00 p.m. using the original mechanism but with the help of an electric motor, not like in the early days when the ball was lifted manually.

After the merger of Australia in 1901, meteorology became a function of the Commonwealth government from 1908 , while the observatory continued its astronomical role. The observatory continued to contribute observations to the astrographic catalog , track the time, and provide information to the public. For example, the observatory provided the Sydney newspapers with the rising and setting times of the sun , moon and planets every day . A proposal to close the observatory in 1926 was narrowly avoided, but by the mid-1970s, increasing problems of air pollution and city light made work at the observatory more and more difficult . In 1982, the government of New South Wales decided to convert the Sydney Observatory into a museum for astronomy and related fields under what is now the Powerhouse Museum .

In November 1821, Governor Brisbane arrived with a set of astronomical instruments, a plan for an observatory, and two personal assistants with astronomical expertise: Carl Rümker and James Dunlop . Brisbane established an observatory in the governor's residence in Parramatta . Problems developed between Brisbane and Rumker. Rumker lost his position and it was not until Brisbane was recalled that Rumker was reinstated by the Colonial Secretary. The following year, the new governor, Ralph Darling, appointed Rumker a government astronomer, who became the first to hold the title in Australia. In 1831 Dunlop was appointed superintendent at the observatory, Rumker lost his position again during a visit to London.

Brisbane's instruments remained in Parramatta on his departure and were used in this observatory until it was closed in 1847. The recommendation for the closure came from a commission appointed by Governor Charles Augustus FitzRoy at the request of London. Dunlop became increasingly frail and therefore careless, which is why the Parramatta Observatory fell into disrepair. The instruments were placed in an arsenal at the urging of Phillip Parker King , a leading astronomer in Australia.

Construction of the observatory

King argued that a government observatory should be established, not just the proposed time ball. King's preference for Fort Phillip as the location was eventually accepted. In the eight years from Edmund Blacket's humble plan for the Zeitballo Observatory from 1850 to its completion, the plans were gradually expanded. The plan from 1850 envisaged a 4 by 4 meter room for a transit telescope and a timing device with a small vestibule. In 1851 an enlarged version was presented to the colonial secretary, but it did not have a time ball tower, as neither King nor the colonial architect Blacket knew how it was supposed to work. The observer's need for an apartment was established.

The plans were redrawn over the next few years. When Blacket stepped down in 1854 to design and oversee the construction of the University of Sydney , plans were underway for an observatory that would be both functional and architectural. Blacket's successor, William Weaver, replaced him in the observatory project. Weaver was named a colonial architect in October 1854. His correspondence with Blacket in the early years shows that Weaver was much happier directly supervising work than he was when performing his desk-bound role. As the head of an overloaded department, he complained:

"The arrangements for the performance of the various works, the official correspondence, the number of reports, and the examination of accounts, absorb nearly the whole time of the head of department, who practically can have little or no professional oversight of any work. "

"The arrangements for carrying out the various tasks, the official correspondence, the number of reports and the checking of the financial statements take up almost the entire time of the department head, who has practically little or no professional control over the work."

A select committee of the Department of Colonial Architects questioned an overpayment to the stonemason entrepreneur of the Dead House on Circular Quay in August 1855 and accused him of defrauding the government. Weaver, as the head of department, was accused of negligence in paying him and subsequently called for his resignation with public outrage. Weaver was a colonial architect for only 18 months, and of the two most important architectural works that came from his department during his tenure, the government printing office on the corner of Phillip Street and Bent Street is no longer and the Sydney Observatory has been attributed to his successor. Indeed, in August 1855 , William Denison approved Weaver's plans for "an observatory and astronomical residence" after some of the specifications provided by Denison had been incorporated. When construction began a year later, the new colonial architect Alexander Dawson took these plans for implementation.

Little more was done until William Denison's arrival as governor general in January 1855. Denison saw an observatory as an important addition to the colony . As a result, the £ 600 allocated for the time ball and building was topped up by an additional £ 7,000 for a full observatory, and Denison wrote to the Royal Astronomer asking him to find a competent astronomer. Plans and estimates were submitted in August 1855, but Denison decided to postpone the final decision on the location and design until the astronomer's arrival.

Alexander Dawson replaced Weaver as colonial architect in April 1856, and the new government astronomer, Reverend William Scott, MA, arrived with his family that October. Offers for the construction were put out to tender in February 1857. The successful providers were Charles Bingemenn and Ebenezer Dewar. The plans used appear to have been the work of Dawson rather than any of his predecessors, as Scott gave numerous references to consultations with the colonial architect about the design of the building. Additional work was approved after Bingemann and Dewar won the tender. This included adding a telescopic dome and raising the time ball tower. This greater height caused some dismay for Scott as it obscured part of the eastern sky.

The completed building combined two architectural directions for the first time in a large building in Sydney: the Italian High Renaissance palazzo and the Italian villa . These contributed to the symmetry of the townhouse facade for the residence and to an asymmetry for the observatory, which arose from the special needs of the passage room, the equatorial dome and the time sphere tower. The building was thus raised from the basic necessity to the fashionable style. Dawson's budget had enabled him to emphasize the distinction between private and public, between domestic and official. The style and shape were overlaid with early Victorian theories of fitness and association. This style should be chosen to emphasize the type and status of the building, and in some cases its location.

Operation from 1858 to 1980s

Scott moved into residence in 1858 and began testing the Zeitball in June. His initial equipment was modest, mainly Parramatta's instruments. However, he received the money for an equatorial telescope . In 1862 Scott resigned and recommended the well-known amateur astronomer John Tebbutt as his successor. Tebbutt declined the offer and the search for a replacement began. In the meantime, his assistant Henry Chamberlain Russell was in charge of the observatory. In January 1864, the new appointee, George Robarts Smalley, arrived, and Russell was his deputy.

In 1870 Smalley died and was replaced by Russell. Russell's talent, entrepreneurial flair, in-depth knowledge of the workings of the New South Wales political and bureaucratic system, and longevity gave him a 35-year tenure as a government astronomer and made him the grand old man of physics in the colony. During Russell's time, the Sydney Observatory reached its professional peak, particularly from the 1870s through the 1890s. Russell wasted no time urging the government on the necessary physical and instrumental resources to carry out his astronomical programs at the observatory. The addition of a west wing designed by colonial architect James Barnett was the major work that resulted. It provided a large room on the first floor for Russell, a library, a second equatorial dome on a tower at the north end to compensate for the blind spot created by the time sphere tower. An enlarged Muntz metal dome was also installed on the old equatorial tower to accommodate a new Schröder telescope. The telescope is still a valuable and functional possession to this day.

Russell also focused on improving the residence, claiming it wasn't big enough to house his family. In 1875 Russell succeeded in securing an extension to the observatory. Like his predecessors, he had dealt with the restrictive nature of the observatory's location, which made the use of meteorological and astronomical instruments difficult, if not impossible. This extension, along with the neighboring signaling station, gives the site its current symmetrical perimeter. The astrographic catalog was Russell's greatest commitment and influenced the programs at the observatory for 80 years. His interest in the application of photography to astronomy and a visit to Paris in 1887 led Russell to participate in a " large catalog of stars ". The Sydney Zone of the Catalog (-52 ° to -64 ° s) was a huge logistic venture and was not practically completed until 1964. Russell died in 1907 after a long period of retirement for health reasons. His assistant Alfred Lenehan was appointed government astronomer and in 1907 government astronomer. However, in 1906 a premier conference decided that the Commonwealth government would take over the meteorological work and leave astronomy to the states. Thus the observatory's meteorological department became a Commonwealth agency under the direction of a former observatory official, Henry Hunt . Lenehan and Hunt argued constantly and did not develop a good working relationship.

In January 1908, Lenehan had a stroke and never returned to work. At the same time, the Commonwealth Agency moved into the observatory's residence. William Edward Raymond, the officer in charge of transit operations, was the officer in charge for four years until the appointment of William Ernest Cooke in 1912. Cooke was lured to Sydney by the Perth Observatory with the promise of a new location in Wahroongah free of the city's lights and traffic, the purchase of modern instruments, and a trip around the world to examine the latest developments. None of this happened during Cooke's fourteen years at the observatory. In 1916, the observatory's visitor committee was reorganized. Russell let it decay during his tenure and in 1917 the residence was again inhabited by astronomers.

All government astronomers from Scott to Cooke were concerned about increased city light, vibration from traffic, and magnetic disturbance that made the Flagstaff Hill location increasingly unsuitable. Recommendations were made in 1864 by Smalley and others in the first quarter of the 20th century. While Russell had managed to move the astrographic telescope to Pennant Hills , there was general concern about the response to the cost of moving the entire observatory. In July 1925, Cooke wrote to his minister, pointing out the problems on the ground and with the equipment. The State Cabinet took him at his word and decided in October to close the observatory instead of paying for the removal and refitting. Protests from the Visitors Committee, the Royal Society of NSW , the NSW division of the British Astronomical Association , the University of Sydney and interested members of the public, however, caused the government to change its mind and allow the observatory to continue - but with greatly reduced staff and program. Most of the staff were transferred to other departments, and Cooke was retired the following year. Only the time ball and the conclusion of the astrographic program remained. This experience prevented future government astronomers in their arguments for a new location.

Two world wars , a great depression and commitment to a logistically demanding astrographic program all contributed to diminishing the vitality of the observatory in the 20th century. Deploying vital resources to the astrographic program became something of a nightmare over the course of the 20th century . The government astronomers could not suspend or cancel the program even if they thought it was desirable. At the same time, the fulfillment of the international obligations from the program made a significant contribution to the survival of the observatory.

With the program completed in 1964 and the final volume published in 1971, it was feared that the days of the observatory were numbered. Other fundamental reasons also contributed to the fact that the observatory was no longer sustainable. The transfer of meteorology to the Commonwealth in 1908 eliminated the observatory's most prominent civil service, electrical telegraphy and radio had diminished, and the need for local navigation and time services had become obsolete over time. The city's ambient light began to limit astronomical observation, although the place was still suitable for time-consuming analysis of the observations and other astronomical work along with functions such as a public observatory and a center for public and media inquiries.

The period after World War II was an exciting time for astronomical development in Australia, especially in radio astronomy . These developments bypassed Sydney, although the government astronomer Harley Wood was closely involved as the first President of the Astronomical Society of Australia (ASA) and coordinator in 1966 and the first general assembly of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in the southern hemisphere was held in Sydney in 1973 . With no major capital resources to develop its own specializations in the West, Sydney remained tied to its traditional role. Even so, there was some positive activity at the observatory. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Wood observatory experienced a modest renaissance. The number of employees was increased and new equipment was purchased. Both the Sydney and Melbourne sections of the Astrographic Catalog have been completed and published. A new domed building was erected in the southeast corner of the observatory to house the Melbourne star camera, which replaced the original Sydney camera. A new survey of the southern sky was begun, and by 1982 Wood's successor, William Robertson, had completed the photography and the measurements were in progress. Education was another aspect of the observatory's work that Wood developed. It was always one of his goals that more and more visitors, including school students, visit the observatory.

These activities earned the Sydney Observatory respect in astronomical circles, but its image in the New South Wales Parliament and associated civil service remained poor. Wood's annual reports did nothing to improve this situation. They didn't give the observatory a sense of excitement or worth.

Deactivation as a functioning observatory

The observatory's resolution was the same as it was fifty years ago when Cooke emphasized the need for a new location. The chairman of the visitors' committee wrote a letter to the prime minister in 1979 demanding the establishment of a remote observation site for the observatory and highlighting the difficulty of the conditions at the existing site. This coincided with a nationwide review of astronomy facilities commissioned by the ASA and led by Kevin Westfold, Professor of Astronomy at Monash University (1980). This concluded that astronomy is a federal responsibility and that resources should be dedicated to research, with radio astronomy highlighted. It should also be noted that the state of New South Wales was in financial difficulty. This pressure led to a letter from the Prime Minister in June 1982 announcing his decision to transfer the observatory to the Museum of Applied Arts and Science and to cease scientific work. Despite letters from international astronomers and a coordinated effort by the now retired Harley Wood, the government did not overturn its decision.

In July 1984, the Secretary of State for Works, Ports and Roads announced a $ 800,000 project to restore the Sydney Observatory for astronomy instruction, a public observatory and astronomy museum. While the importance of the exterior facade was recognized, the interior decoration was less fortunate. When the museum was created within the building, almost all of the instruments and equipment, as well as furniture and furnishings, were gradually brought into the museum's shop. The astrographic building was demolished and the dome, instruments, and most of the glass plate and paper collection were brought to Macquarie University for future research .

In 1997 the observatory was renovated, this time the instruments were returned to their original location or on display. The exhibition theme "In the light of the southern stars" also included the instruments of the Parramatta observatory and indigenous astronomy. In 1999 a major stone carving repair project began on the observatory building. This lasted until 2008. In 2002, Kerr's maintenance plan was updated, this time to complement the relocation and interpretation of the instruments.

In recent years a number of important astronomical events have occurred, in particular Halley's Comet (1986), the impact of Shoemaker-Levy 9 on Jupiter (1994), Mars at its next encounter (2003), the transits of Venus (2004, 2012), Comet McNaught (2007), planetary alignments and eclipses. Thousands of people came to the observatory to view these events through telescopes and to see thematic exhibitions. In addition, the observatory informed many more people about these events, either directly or through the media.

In 2008, for the 150th anniversary, the signal station building was stabilized, one of the two original flagpoles was rebuilt, and an archaeological study was carried out around the base of the fort under the direction of New South Wales Government Architects, Building Design and Heritage Office and Casey and Lowe initiated. Original fortress foundations were uncovered and the base of a room that was once bomb-proof within the fortress wall foundations.

In 2009, permission was given to set up a temporary marquee for a limited period to raise funds. In addition, the astrographic dome and instruments from Macquarie University have been returned to the museum, awaiting conservation , on a Heritage New South Wales-approved structure on the observatory grounds. The most important change to the Sydney Observatory in 50 years, the new Eastern Dome, was opened on January 27, 2015 by Deputy Prime Minister Troy Grant and Minister for Disability Services , John Ajaka .

heritage Site

The Sydney Observatory was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on December 22, 2000 after meeting the following criteria:

"The place is important to demonstrate the course or pattern of cultural or natural history in New South Wales."

The dominant position of the observatory next to and above the port city and later the city of Sydney made it the location for a number of changing uses. All of this was important and reflected changes in the development of the colony. The place is associated with a wide variety of historical figures, most of whom contributed to the design of this place. These include colonial governors, military officers and engineers, convicts, architects, and astronomers.

"The location is important to demonstrate aesthetic features and / or a high level of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales."

The height of the site, overlooking the port and city, as well as the view framed by the ancient fig trees of the surrounding park, make it one of the most pleasant and spectacular places to be. The picturesque Italian character and stylistic interest of the observatory and residential building, as well as the high level of skill in the masonry (both stone and brick) of all the major structures on the site, together form a district of unusual quality.

"The place has the potential to provide information that will help understand the cultural or natural history of New South Wales."

The structures that have been preserved, both above and below ground, are themselves physical documentary evidence of 195 years of changes in use, technical development and lifestyle. As such, they are an ongoing resource for investigation and public interpretation.

Web links

- Official website (English)

- Sydney Observatory, Upper Fort St, Millers Point, NSW, Australia (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Office of Environment & Heritage: Sydney Observatory. In: New South Wales Governement. Accessed June 17, 2020 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z NSW Government: About the Observatory. In: Sydney Observatory. Accessed June 17, 2020 (English).

- ^ NSW Department of Education: Observatory Hill Environmental Education Center. In: Observatory Hill. Accessed June 17, 2020 (English).

- ↑ 7.25-inch telescope, Sydney Observatory. Accessed June 17, 2020 (English).

- ^ Wood, H .: Sydney Observatory 1858-1983. In: Proceedings of the Astronomical Society of Australia, Vol. 5, Issue 2, p. 273, 1983. Retrieved June 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Toner Stevenson: Accessing the sky - building Sydney Observatory's new dome - post 8. In: Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Accessed June 17, 2020 (English).

Attribution

Sydney Observatory ( English ) In: New South Wales State Heritage Register . Office of Environment and Heritage. H1449. Retrieved October 13, 2018. CC-BY 4.0 license