Tiruchinnam

Tiruchinnam , ( Tamil திருச்சின்னம் tirucciṉṉam [ t̪iɾɯt͡ʃinːʌm ]), also tirucinnam, tiruchchinnam, Thiru-Chinnam is a straight natural trumpet of brass , in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu is used in religious rituals. In contrast to other ceremonial trumpets, which are generally played in pairs by two musicians, and with all trumpets, one musician usually plays two tiruchinnam at the same time. Tiru means “holy” in Tamil and chinnam stands for “wind instrument”.

Origin and Distribution

In terms of instruments, the large group of trumpets includes wind instruments made of different materials and shapes (sheet metal, wood , calabash , snail horn ) with or without a mouthpiece , the sound of which is produced by vibrating the lips, which generate air oscillations in a tube. Many trumpet instruments have been assigned a magical-religious meaning that has existed since ancient times. Such an association is expressed in the same way in the stories about flutes , especially shepherd's flutes (cf. the shepherd's flute kaval ). While the diverse musical possibilities of the flute led to the idea of a magical "flute language" for establishing contact with the otherworldly sphere, the simple trumpets were limited to the production of a few tones, which is why they are for little more than the transmission of signals hunting (hunting trumpets), religious cults and armed conflicts (military trumpets). Because of their Anblastechnik the development difference in the trumpet to a plurality of Eintonflöten bundled Panflöte from, but originated in Africa melody capable orchestra of a series of trumpets (for example, the waza on the border of Sudan and Ethiopia) with which a musician in each case generates only a tone . The ritual requirement to play melodies, as in orchestras with single-tone flutes, such as the Central African hindewhu , or with the structurally related Russian horns (metal trumpets that produce one or two natural tones) does not exist with the trumpets used ceremonially in Asia, which are almost everywhere only used in pairs. A corresponding development towards melody instruments as in Africa or quite differently in Europe did not occur with the Asian trumpets. The curved metal trumpets kombu, which are only used in large numbers in the temple music of Kerala , do not serve to form melodies, but are considered rhythm instruments according to their function in the large drum orchestras.

For the origin of metal trumpets used in religious rituals in India since the Vedic period and for their spread with the Arab-Persian tradition in the Mughal period as a ceremonial instrument on festive occasions, see Bhankora .

A straight trumpet is probably first depicted on a Sumerian stone relief that dates back to around 2600 BC. Is dated, a horn blown out of copper from there is dated around 2400 BC. Mentioned as a ritual instrument. The originals of small metal trumpets from the Iranian highlands are almost as old . Bronze Age Lurs , which existed from the end of the 2nd millennium to the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Mostly found in pairs in Northern Europe in BC, because of their curved shape and number, they are probably imitations of previously ritually blown ox horns. Horns such as the oriental ram's horn shofar have always had a specific magical-religious meaning, while that is also mentioned several times in the Old Testament straight metal trumpet chazozra functioned not only for religious rituals, but also as a symbol of worldly power. The chazozra was about 40 centimeters long and was made of hammered silver sheet, as can be seen from the biblical texts. It is not clear whether it goes back to the ancient Egyptian pair of trumpets ( scheeb ) from the tomb of Tutankhamun (14th century BC) or whether it is related to Phoenician trumpets.

Ancient Indian illustrations from the 1st century BC. BC prove that in Vedic texts from the 1st millennium BC The use of snail horns and long trumpets mentioned in the 2nd century BC, which are still part of the ceremonial instruments in India and neighboring regions. Long trumpets with a conical tube are known in northern India as karna ( karnat, karana ) and come from Western Asia because of their affinities with Persian qarnā , Latin cornu and Celtic corn . The brass or copper trumpets in the Himalayas and its fringes also have a conical tube with a wide bell , including the thun chen played by Tibetan monks in Ladakh or dungchen in Tibet, the ponga of the Newar in Nepal and the bhankora in Uttarakhand . The long bhungal in Rajasthan has a two-part conical tube made of bronze. The Oraon, an Adivasi group in Bihar , use the almost 105 centimeter long cylindrical copper trumpet bhenr . In Tamil Nadu, in addition to the tiruchinnam , the longer, predominantly cylindrical metal trumpet ekkalam and the gowri kalam with a three-part conical tube are in use. In addition to the straight metal trumpets, there is or was the rare konattararai trumpet in Tamil Nadu with a conical, slightly curved tube, which was always played in pairs in Hindu temple rituals.

The peculiarity of the tiruchinnam compared to probably all other trumpets is the simultaneous playing of two instruments by one musician. This way of playing occurs in South Asia with some double flutes , for example with the North Indian alghoza and in Pakistan with the doneli . Double reed instruments with two separate play tubes based on the example of the ancient Greek aulos appear on ancient Indian reliefs in northwestern India (at the stupa of Sanchi , 1st century BC, and in Gandhara , 2nd / 3rd century AD), if the presence of foreign musicians from the west is to be pointed out. They later disappeared from Indian music. A rare exception is the horn pipe pepa played in regional folk music in Assam .

Curt Sachs (1940) provides a relationship between the shape and size tiruchinnam and ancient Egyptian and Assyrian forth trumpets. In addition to the linguistic relationship between the ancient Egyptian and the ancient Indian bow harp - ban, ben or bain in Egypt, bin or vina in India - this relationship serves as evidence for the thesis of the origin of a high-ranking Dravidian culture from Mesopotamia or Egypt from the 3rd millennium onwards v. BC, before the Dravids were driven to southern India by the immigrant Aryans .

In contrast to the thesis repeated by BC Deva (1978) and Edward Tarr (1988) that the transfer of culture from ancient Egypt to India was made possible by sea trade, there is historical evidence that Indian culture spread from the East Indian coast to Southeast Asia in the first centuries AD. The snail horn depicted in Borobudur (9th century) in Java , Sanskrit shankha , modern Hindi shankh, can be found in ancient Javanese literature as cangka, maracangka and sungu . In Hindu rituals in Bali which is Sangka and Sungu -called conch used to this day. The Sanskrit name karana ( karna, kaha ) for a metal trumpet does not appear in Old Javanese texts, but the presumably related names for trumpets kahala, kalaha and kala are also mentioned several times in connection with cangka . Two conical trumpets based on Indian models can be seen on a relief at the Candi Jawi (Jawi Temple), which was built in the 13th century during the Indianized Kingdom of Singhasari on Java. What is unusual is that both trumpets are blown by a musician who points them upwards at an angle of about 45 degrees. Jaap Kunst (1927) considers the represented wind instruments to be identical to today's double trumpet tiruchinnam .

Design and style of play

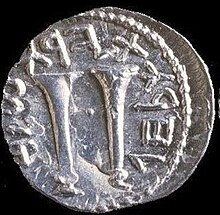

The tiruchinnam consists of a relatively thin cylindrical brass tube to which a conical bell is attached with a wide bulge at the connection point, which ends in a flat plate. The total length is about 75 centimeters. A mouthpiece is missing, as in some other Indian trumpets; in this case it would otherwise not be possible for a musician to blow two instruments at the same time. Each trumpet is grasped with one hand in the upper third of the tube and pressed against the lips so that they form an acute angle to one another. A individually played tiruchinnam is also held at the mouth with the second hand. Usually two tiruchinnam are connected in the middle by a cord. While the players of double flutes or double reed instruments usually add a drone tone to the melody with the second playing tube , the few tones are only supposed to be amplified with two tiruchinnam that are blown at the same time and have almost the same mood.

In addition to its ritual function in temple service, the tiruchinnam used to be blown on the street by beggars and the lower Dasaris caste. Only drums, idiophones and wind instruments are used for Indian temple music , no string instruments. Wind instruments played at temples in Tamil Nadu are shankh (snail horn), bhuri (curved brass horn ), ekkalam (straight trumpet made of brass or copper), tiruchinnam and kombu (metal trumpet bent in a semicircle or S-shape).

The rarely used tiruchinnam belongs to the mangala vadyam (the "auspicious, blessing musical instruments") and is played at Vishnu temples at the beginning of a ceremony and during the procession. The tiruchinnam was also sometimes used at temples dedicated to Shiva , for example with just one instrument at the Tyagaraja temple in Tiruvarur . Mostly the tiruchinnam belongs to the cult music of village temples like the other instruments kanjira (small frame drum with a bell), pambai (double drum), davandai ( hourglass drum ), udukai (short version of the hourglass drum idakka ), thambattam (large kettle drum made of clay) and silambu ( Anklets of dancers).

literature

- Alastair Dick: Tirucinnam . In: Grove Music Online , January 20, 2016

- Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975

- Pichu Sambamoorthy: Catalog of Musical Instruments Exhibited in the Government Museum, Chennai. (1955) The Principal Commissioner of Museums, Government Museum, Chennai 1976, p. 17 and Plate III, 8

Web links

- Trichnan, Tirucinnam. Europeana Collections (image)

- Long room pair tirucinnam. Franz Födermayr Collection, University of Vienna (picture from LP Josef Kuckertz - South Indian Temple Instruments , title B14, sound documents on musicology, ethnomusicological department of the Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin, mono recordings from 1969)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus P. Wachsmann : The primitive musical instruments. In: Anthony Baines (ed.): Musical instruments. The history of their development and forms. Prestel, Munich 1982, pp. 45f

- ^ Curt Sachs : Handbook of musical instrumentation . (1930) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1967, p. 258

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse, 1975, p. 816

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid: Mesopotamia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1984, p. 60

- ↑ Sibyl Marcuse, 1975, pp. 745f

- ↑ Joachim Braun: Biblical Instruments. 3. Old Testament instruments. (iii) Ḥaṣoṣerah. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Museum of Performing Arts. Gallery of Musical Instruments. Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi undated

- ↑ Konattararai pair of longitudinal horns. Collection Franz Födermayr, University of Vienna (illustration from LP Josef Kuckertz - South Indian Temple Instruments , title B15, sound documents on musicology, ethnomusicological department of the Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin, mono recordings from 1969); Peter Crossley-Holland: South Indian Temple Instruments by Josef Kuckertz. (Review of this LP) In: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 15, No. 2, May 1971, pp. 308-310

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume 2. Ancient Music . Delivery 8. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, pp. 34, 62, 152, 158

- ^ Francis W. Galpin: The Music of the Sumerians: And Their Immediate Successors, the Babylonians & Assyrians. University Press, Cambridge 1937, p. 28

- ^ Curt Sachs: The History of Musical Instruments. WW Norton & Company, New York 1940, p. 153

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: Musical Instruments of India. Their History and Development. Company KLM Private Lilited, Calcutta 1978, p. 111

- ↑ Edward Tarr : The Trumpet. BT Batsford, London 1988, p. 30

- ^ Jaap Art : Hindu-Javanese Musical Instruments. (first in Dutch in 1927) Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag 1968, p. 31f

- ↑ P. Sambamoorthy, 1976, p. 17

- ↑ M. Lalitha, M. Nandini: Hear the sound of tiruchinnam. The Hindu, March 24, 2016