Karna (trumpet)

Karna ( Arabic , Persian کرنا, Karna, qarnā , Hindi Karna, Tajik карнай karnai even karnaj, Uzbek Karnay, Kazakh керней Kernei ) is a natural trumpet made of metal, whose name first in the biblical book of Daniel is mentioned that in the Middle Ages to the Persian military bands and the Indian Mughal Empire for Representative orchestra naqqāra-khāna belonged and is widespread with this name in ceremonial music in Central Asia and North India to this day .

Since the middle of the 3rd millennium BC Trumpets known from Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt served in both regions as signaling instruments during ceremonies, wars and work assignments. They could only produce a note or two in a given rhythm. Karnā goes back to Aramaic qarnāʾ , Hebrew qeren and Akkadian qarnu . In addition to the Arabic word būq for brass instruments in general ( horns and trumpets), in medieval Arabic texts nafīr predominantly denoted a slim, cylindrical, shrill metal trumpet, būq a slightly shorter, conical trumpet and karnā a conical, sometimes S-shaped, up to two meters long curved trumpet. The trumpet types nafīr and karnā were used in Iran together with various drums and other percussion instruments in naqqāra-khāna until the beginning of the 20th century . Today the karnā in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan is a long, predominantly cylindrical metal trumpet, and in northern India it is a straight, conical metal trumpet that can be long and thin or short and wide.

origin

Ritual trumpets

The oldest trumpet instruments, which caused the blown air in a tube to vibrate by periodically changing lip tension according to the sound generation principle of the upholstered pipe , consisted of found animal horns, bones, snail horns or plant materials such as calabashes or bamboo tubes. Later the natural forms were recreated with bark, wood or sheet metal. The distinction between these simple wind instruments in natural trumpets or natural horns cannot be determined with clear criteria; animal horns or short, curved and conical tubes are more commonly referred to as "horn" and longer, straight and predominantly cylindrical tubes made of plant material or metal rather than "trumpet". Trumpet instruments are generally blown lengthways , but African animal horns such as the South African antelope horn phalaphala are mostly blown across.

Regardless of shape, material and name, natural trumpets have been used primarily for magical and religious purposes and less as musical instruments since ancient times. They are also hardly suitable for this because they can only produce one, two or a few tones of the natural tone series . In the beginning there were cylindrical wooden tubes ("longitudinal tubes") like the aporo in East Africa to this day , which can be blown from both sides. Labwor women in northeast Uganda greeted their men who had successfully returned from hunting or plundering a neighboring village with a low humming sound. Otherwise, participants at funerals heard the hum of such magical long rooms (including the mabu of the Solomon Islands ) the voices of the ancestors. Presumably younger than Schwirrgeräte , but even older than drums , were among the longitudinal tubes of the first ritual sound producers.

Wooden trumpets of the Swiss alphorn type, such as the Ukrainian trembita and the northern Polish bazuna , may have passed into pastoral culture as imitations of ancient metal trumpets, more likely they belong to a general Indo-European pastoral tradition. In this, the trumpets serve more as signaling instruments and only partially for ritual purposes, for example at funerals and in the case of the wooden trumpet puch der Mari in Russia for tree worship. A similar ritual function at funerals is mentioned by the Naga long trumpets in Assam (northeast India), whose conical tube - possibly as a replica of the metal ritual trumpets ( dungchen ) used in the Himalayan region - consists of several nested bamboo tubes of different sizes and which are otherwise used by shepherd boys as signaling instruments were used.

The musical development of some single-tone trumpets in Africa took a special path, which, like the waza orchestra in the Sudanese-Ethiopian border area, whose members play melodies with differently tuned calabash trumpets, each of which produces only one note. The group of blown by a musician trumpets behaves like a musical from Eintonflöten bundled Panflöte . In Europe, on the other hand, the introduction of valves , keys and tuning slides helped brass instruments to obtain a chromatic range of tones and thus to the broad musical possibilities of the trumpets far beyond their previous use in hunting and the military. Neither one nor the other development took place in Asia and traditional Asian trumpets with their magical-religious background have remained ceremonial instruments for secular and religious occasions, which are hardly suitable for forming melodies.

Antique trumpets

The earliest trumpet-like finds made of silver and gold are 10 to 20 centimeters long and come from the Iranian highlands (excavated in Tepe Hissar , Gorgan and Schahdad, Kerman province ). They are found between 2200 and 1750 BC. And belong to the oasis culture further north in Central Asia ( Bactria – Margiana Archaeological Complex, BMAC). Probably the oldest representation of a straight trumpet can be seen on a fragmentary Sumerian stone relief from Ḫafāǧī , which dates back to about 2600 BC. Is dated to the Mesilim period. Around 2400 BC In Mesopotamia, trumpets were mentioned in writing as ritual instruments. Illustrations from the middle of the 13th century BC. According to BC, they were end-blown copper trumpets that were slightly curved as an imitation of an animal horn. Northern European Bronze Age Lurs from the end of the 2nd millennium to the middle of the 1st millennium BC BC, which were mostly found in pairs, with their curved shape presumably represent further developments of previously ritually blown ox horns.

The presumably oldest Egyptian trumpet image is a relief in the vestibule of the mastaba of Kagemni (in Saqqara ) from the transition of the 5th to the 6th dynasty (around 2400 BC), which depicts a number of dignitaries crossing the Nile. A boy stands between the rowers, holding a wind instrument horizontally in his right hand. Although only a thin tube can be seen without a bell, Hans Hickmann (1961) recognizes a trumpet that is used in a death cult because of the one-handed playing position. In ancient Egypt , metal trumpets called sheneb , according to most of the pictorial representations, were blown by a player who - as in the burial chapel of Nebamun , at the beginning of the 14th century BC. BC - a troop of marching soldiers or led a parade, the remaining trumpets belonged to royal ceremonies. Two well-preserved short trumpets come from the tomb of Tutankhamun (ruled around 1332–1323), which confirm that the represented instruments were metal trumpets.

It is unclear to what extent the musical instruments mentioned in the Old Testament had a cultural classification according to fixed criteria; In any case, they had a symbolic meaning at the time, according to which they are not consistently classified and with certain overlaps. Musical instruments of the early nomadic period with a magical meaning include the curved ram's horn shofar , the straight metal trumpet chazozra ( hasosrah ), the frame drum tof and the cymbals mesiltayim (in the Septuagint kimbalom ). There were also instruments of urban music and art music during the kingdoms (lyre kinnor , larger plucked instrument nevel and wind instrument chalil ). The sacred musical instruments at the temple again included the shofar, chazozra, chalil, kinnor, nevel and mesiltayim .

The Hebrew name of the metal trumpet made of hammered silver, chazozra (plural chazozrot ), occurs 31 times in the Old Testament, in most cases as a cult instrument of the priests and only three times in connection with war (including ( 2 Kings 11.14 EU ) ). According to Joachim Braun (2002), chazozra is probably connected with the Arabic verb hsr ("howl", "scream"), while David Wulstan translates the corresponding Hebrew consonant root with "housing", "fencing", hence "tube". Thus the name of the Israelite metal trumpet is not derived from Egyptian ; According to a widespread view, however, the chazozra seems to be derived from the ancient Egyptian military trumpets, schebs , which are similar in shape and material , even if the influence of trumpets of the Philistines or Phoenicians cannot be ruled out. One of the two specimens in Tutankhamun's tomb is 58 centimeters long and made of silver, the other, 49 centimeters long, is made of partially gold-plated bronze sheet. Both grave finds produce two useful notes in approximately the same interval as a trumpet from the Greco-Roman period (1st century BC) that is more than 1000 years younger .

The oldest finds of snail horns used for ritual purposes in Palestine are dated to the Late Bronze Age (Tel Nami, 13th century BC) and Early Iron Age (Tel Qasile, 12/11th century BC), the earliest archaeological evidence for the use of trumpets in Palestine dates from the 3rd century BC. In the biblical place Marescha , which was ruled by the Edomites before it came to Greek power during Hellenism , Hellenistic wall paintings have been preserved, which, as before with the Assyrians, place music in the service of the hunt. The mural in a burial chamber from the 3rd century BC BC shows a trumpet player behind a rider hunting with a long spear. He holds the 120 to 130 centimeter long trumpet, which resembles a Roman tuba , horizontally forward with the outstretched right hand, the left hand on the hip. It is perhaps the oldest illustration of a trumpet in a hunting scene.

The historical karnā and the karna / karnai that occur today in northern India and the Turkestan region are counted among the trumpets because of their slender, cylindrical or slightly conical shape, although their name is derived from a horn mentioned in the Bible. Arabic karnā goes back to Aramaic qarnāʾ , which is related to the Hebrew word qeren . Qeren is a very old word that goes back to an origin in both Semitic and Indo-European languages . The Akkadian equivalent is qarnu . It denotes every type of animal horn and occurs over 70 times in the Old Testament. In some contexts the word qeren also has the meanings “shine” ( Ex 34.29 EU ), “shine” ( Hab 3.4 EU ) and “redeem” ( Ez 29.21 EU ). As “animal horn” qeren stands in different contexts: In ( Gen 22,13 EU ) the ram, which Abraham sacrifices instead of his son Isaac, gets caught in the undergrowth with its horns. In ( 1 Sam 16.1 EU ) the horn is used as a container to fill in oil. In ( Ex 27.2 EU ) the altar is equipped with a horn at each of the four corners. In ( 1 Sam 2,1 EU ) (LUT) Hanna expects the birth of her son Samuel with "my horn is exalted in the Lord". Only once does qeren mean a musical instrument. In the mythical tale in ( Jos 6,5 EU ) of the capture of Jericho , God orders the priests to blow seven ram horns ( qeren ha-yovel ) and to precede the procession with the Ark of the Covenant. In their magical meaning, cross and shofar cannot be distinguished here. Yovel stands for “jubilee”, “jubilee” and “ram”, the consonants yvl mean “lead” and “leader of the herd”.

In the Aramaic Bible ( Targum ) is in ( Ez 7,14 EU the Hebrew word for the loud continuous sound of) shofar with qarnā translated. This becomes salpinx in the ancient Greek Septuagint (instead of the related ancient Greek keres for "animal horn") and in the Latin Vulgate tuba. Thus the word qeren , which is ambiguous in Hebrew and only in one case in a musical context, was undoubtedly understood as a kind of trumpet and handed down in the language versions mentioned.

In the book of Daniel , which was written between 167 and 164 BC, Was written in four places in almost the same form a music group that belonged to the worship of an image of God. It says in ( Daniel 3,5 EU ): “As soon as you hear the sound of the horns, pipes and zithers, the harps, lutes and bagpipes and all other instruments, you should fall down and worship the golden statue that King Nebuchadnezzar erected . "the Aramaic instrument names are in this set qarnā, maschroqītā (Hebrew root SRK, a reed instrument ), qaytrōs (a lyre ), Sabka (small vertical angle harp , in the Vulgate sambuca ) psanĕttērīn (presumably large angle harp), sūmpōnyā (either Bagpipe , term for the entire ensemble or for a drum) and kol zĕnēy ("all kinds" of) zĕmārâ ("musical instrument"). With qarnā , the word for “natural horn”, a trumpet made of metal or clay is probably also meant here.

In the New Babylonian Empire , trumpets were 70 to 90 centimeters long and, as in the ancient Mediterranean, served as signaling instruments: After several campaigns against the Mesopotamian peoples who had not submitted to it, the Assyrian King Sennacherib (ruled around 705-680 BC) Chr.) In his palace in Nineveh show how the deported peoples were forced to work. Two trumpeters standing on a colossal animal figure carved out of stone can be seen on an orthostat relief . The first of the two blows a horizontal, cylindrical, slightly conical trumpet at the end. The other trumpeter holds his instrument down with his left hand while apparently giving instructions with his right hand outstretched. In this scene the trumpet serves as a signaling instrument for the workers' columns, to whom the trumpeter passes the orders.

What the qarnā mentioned in the Book of Daniel could have looked like is shown at the same time from the Parthian Empire . The relief from the capital Hatra , created in the 3rd century BC, shows the panpipe, a double reed instrument, a wind instrument with two chimes (of the aulos type ) and the trumpet on wind instruments . The latter was about 50 centimeters long, made of clay and had a wide cylindrical tube with a wide funnel-shaped bell, but no mouthpiece. The Parthians played the trumpet at weddings and other festive occasions.

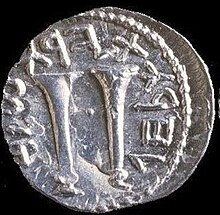

Like qarnā , the Greek word bukane could denote a shepherd's instrument (cow horn) and a military horn in ancient times . For the Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (around 37 - around 100 AD), the bukane played in the temple was an invention of the prophet Moses , which he described as a straight wind instrument made of silver with a slightly thicker tube than the aulos , a mouthpiece and a bell as described for the Salpinx . Although this imprecise description could also apply to reed instruments, the two wind instruments on the Bar Kochba coins are often considered to be trumpets that could be forerunners of the medieval Arabic nafīr . Other authors recognize a pirouette on the mouthpiece and assume cone oboes. The related Latin name bucina also denotes an animal horn used by the shepherds and a metal signal trumpet used by the military.

The trumpet used in the temple can be found in a late version on a wall painting in the synagogue of Dura Europos around 250 AD, on which King David can be seen with his lyre kinnor and trumpet player. After the conquests of Alexander the Great , from 320 BC The Seleucid Empire, which was formed in the Middle East and reached Central Asia, was used in military operations. The same applies to the Central Asian equestrian peoples who lived in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. Fought against the Chinese. On a rock relief by Taq-e Bostan near Kermanshah in Iran is a Sassanid military orchestra with trumpets played in pairs, which are similar in shape to the Roman tuba . The relief was created under King Chosrau II (r. 590–628) and shows the king riding a stag hunt, over whom a servant is holding a parasol. Behind the two, on the right edge of the relief, there is a military band in three rows. The large kettle drum (Arabic kūs ), the small kettle drum pair ( tāsa ), a double-headed tubular drum , the cone oboe ( surnā ) and two musicians with long trumpets blown in pairs can be recognized. This loudly occurring Orchestra differs markedly from the court orchestra on the other side of the king, which is primarily with quiet angle harps chang and the mouth organ Mushtaq plays. The long trumpets are also mentioned several times as karranāy in the Persian national epic Shāhnāme , which was completed in 1010 . At one point in the historical and mythical story written by Firdausi , the trumpet players blow on the backs of elephants while others beat the drums. Even the Greeks used trumpets ( salpinx ), double reed instruments ( aulos ) and drums in their military orchestras . Trumpet-blowing riders on the battlefield are also known from the Celts and Romans. Furthermore, in the Sassanid period in Iran there were kettle drums mounted on horses, which were struck together with trumpet-blowing riders during fights.

After the end of the Roman Empire, there were hardly any trumpets in Europe until the 10th century, there were only a number of curved horns in different shapes and sizes. Curt Sachs (1930) considers the metallic trumba , which was blown in Irish book illuminations for the Last Judgment in the middle of the 8th century, to be a regression of the Roman tuba . A conical trumpet based on the Roman model is together with other wind instruments in a manuscript of the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville from 10/11. Century pictured.

Arabic trumpets

Around 1200, metal trumpets appeared in Western Europe under the old French name buisine , which had been imported from the Muslim Middle East at the time of the Crusades and, according to the poet Wirnt von Grafenberg (13th century), "after the heathen site", that is, were played in an oriental way. The Roman tuba with a conical tube, which disappeared in Europe , was continuously used in the Byzantine Empire . The oriental trumpet was neither a simple imitation of the trumpets from the ancient Mediterranean region nor of the Sassanid instruments, but also adopted later Persian developments. The long cylindrical trumpets with wide bulges at the end of the pipe sections, which came to Europe at the time of the Third Crusade , shaped the European metal trumpet type until the end of the Middle Ages and are depicted in large numbers on frescoes in Italian churches. A fresco from the end of the 11th century in the church of Sant'Angelo in Formis near Capua with four angels blowing long conical and slightly curved trumpets is considered to be the earliest depiction of imported oriental trumpets.

According to the Arab historian Ibn Chaldūn (1332–1406), the trumpet ( būq, plural abwāg ) and the drum ( tabl ) were still unknown in the military system in early Islamic times . The unspecific Arabic name būq for all brass instruments ("trumpet" or "horn"), which has appeared in literature since the 9th century, is probably derived from the Latin bucina and, among other things, from Georgian buki for a natural trumpet related to the Roman tuba , related to albogue for horn pipes in Spain and to bankia , a regional name for the S-shaped curved trumpet shringa in India. In the 7th / 8th In the 19th century, būq was not yet a war trumpet for the Arabs, as the snail horn blown on the Arabian Peninsula was probably called . According to the historian Ibn Hischam in the 9th century, būq was used in the centuries before only to refer to the war trumpet of the Christians and the wind instrument for the call to prayer among the Jews.

Instead, the early Islamic Arabs used the reed instrument mizmar and the rectangular frame drum duff when fighting . In the 10th century, the military orchestra, with the trumpet būq an-nafīr , the cone oboe surnā , the kettle drums of different sizes dabdab and qasa, and the cymbals sunūj (singular sinj ) was an important symbol of representation for the Arab rulers. As the Fatimid caliph al-ʿAzīz (r. 975–996) invaded Syria from Egypt in 978, he had 500 musicians with signal horns ( Clairon , būq ) with him; the sources also report large Fatimid military orchestras on other occasions. Arab authors around this time distinguished the metal trumpets būq and nafīr . Between the 11th and 14th centuries, the instruments used by the military bands became much more diverse and, consequently, the musical possibilities should also have expanded.

When the army of the Egyptian Mamluks launched the Sixth Crusade in 1250 , which was led by the French King Louis IX. was on the advance in Egypt, successfully fought back, the Sultan's military band played a part in the victory. During the rule of the Mamluk Bahri dynasty in the 13th century, the sultan's military orchestras included 20 trumpets, 4 cone oboes, 40 kettle drums and 4 other drums. The Mamluk army was commanded by 30 emirs , each of whom had their own musicians who played 4 trumpets, 2 cone oboes and 10 drums. The military bands were called tabl-chāna ("drum house") because they were kept in a room in the main gate of the palace.

Arabic sources provide information about the names and approximate shape of the oriental trumpets in the late Middle Ages. The Arabic name nafīr was first mentioned in the 11th century among the Seljuks . The original meaning of nafīr was "call to war", which is why the trumpet used accordingly was called būq an-nafīr . In today's Turkish , nefir stands for "trumpet / horn" and "war signal ". A distinction must be made between the straight nafīr trumpet of the early Ottoman military bands ( mehterhâne ) and the later coiled boru trumpet, which dates back to European influence . On Nafir Spanish is añafil returned for a medieval Spanish long trumpet and the German word Fanfare is allegedly Anfar , the Arabic plural of Nafir basis.

The Arabic nafīr was probably mainly a long, cylindrical metal trumpet with a high-pitched sound that was better suited for signaling than the deeper and duller sound of the conical trumpets. According to the Persian music theorist Abd al-Qadir Maraghi (bin Ghaybi, around 1350–1435), the nafīr was 168 centimeters (two gaz ) long. The tonal difference comes from the vocabulary of the Iraqi historian Ibn al-Tiqtaqa (1262-1310), according to which the nafīr player " screamed out" the trumpet ( sāha ), while the player of the conical trumpet, which is referred to here as būq , be Instrument "blew" ( nafacha ). Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi described the karnā as an S-shaped bent from two semicircles, which are turned against each other in the middle - like today's shringa in India.

A miniature by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti on the Maqāmāt of the Arab poet al-Hariri (1054–1122) in a manuscript from 1237 shows a caravan with camels and horses on the pilgrimage to Mecca. The distinguished pilgrim in the illustration of the 31st Maqāma travels with his wife in a sedan chair and several servants who go on foot. The musicians play two slim tubular kettle drums ( tabl al-haddsch ) and two trumpets ( būq ), which are conical and relatively short. The illustration of the 7th maqāma in the same handwriting shows that the musicians used different musical instruments depending on the occasion. An Arab military band is shown here, performing with flags and standards. The two trumpets ( nafīr ) are long and cylindrical. Instead of the sleek boiler drum, the military musicians played the small boiler drum pair naqqara , the medium-sized boiler drum kūsāt , the huge boiler drum Kurgat, the cylinder drum tabl and Kegeloboe surnā and some whipped idiophone .

Another type of trumpet is shown in a Persian miniature in a manuscript from the end of the 14th century of the cosmography Aja'ib al-machlūqāt (“Miracle of Creation”) written by al-Qazwīnī (1203–1283 ). The Muslim angel Isrāfīl appears similar to the Christian archangel Gabriel as the herald of the day of the resurrection. He blows the Last Judgment with his trumpet . The two spherical bulges on his trumpet are the junctions of the three parts that make it up: a mouthpiece, a straight cylindrical tube and a funnel-shaped bell.

According to the travelogue Seyahatnâme by the Ottoman writer Evliya Çelebi (1611 - after 1683), the karranāy was a curved trumpet made of silver in the Ottoman Empire in the 17th century , which produced a sound like the scream of a donkey. Sultan Murad IV (reigned 1623-1640) is said to have brought this trumpet back to Constantinople from his successful campaign against Yerevan in 1635 .

Persian trumpets

The long metal trumpet has been known in the Iranian highlands since the Sassanid period (224–651). A tabl-chāna or naqqāra-khāna filled with kettle drums, tubular drums, straight and curved trumpets and reed instruments , which was primarily a privilege of the caliphs and the emirs, was allowed under the Buyids in 10/11. In the 19th century, other dignitaries (ministers, military leaders) who maintained their own army were gradually being commanded. Under the Seljuks in the 11th century, this privilege was extended to a wider circle of authorized people, graduated according to the size of the orchestra. Ibn Battuta described the military at the time of Abu Sa'id , one of the 1316 ruling to 1335 Ilkhan , practiced ceremonies. Accordingly, every emir had an orchestra with drums and trumpets; The regent's main wife and the princesses also had their own drums, which were ceremonially beaten at certain times of the day. When Abū Saʿīd went on a journey, the orchestra would sound, as is also reported for the arrival of other rulers.

According to the two musical theoretical works written by Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi at the beginning of the 15th century, Jame ′ al-Alhān ("collection of melodies") and Maqasid al-Alhān ("meaning of melodies"), the Arabic names būq and nafīr were also im Persian known as wind instruments, where Abd al-Qadir with būq probably meant the reed instrument būq zamrī made of metal . Karnā or karranāy referred to the S-shaped bent metal trumpet in Persia. Another trumpet name he mentions is burgwāʾ , which may belong to boru .

The first Muslim conquerors of South Asia were Arabs of the Umayyad dynasty, who conquered Sindh in 712 . Sometime afterwards, Arab-Persian military music with kettle drums, trumpets and cone oboes will have reached India. The Arabic name for the pair of kettle drums used by the Muslim armies, nagārā , was introduced in India when the Sultanate of Delhi came to power in 1206. While the military bands retained their previous function, they also developed into representative orchestras at the rulers' palaces, which were referred to by the name derived from the drum as naqqara-khana or as naubat . The word naubat goes back to Henry George Farmer (1929) in Arabic nauba , which is used by Abū l-Faraj al-Isfahānī in his work Kitāb al-Aġānī ("Book of Songs") for a group of musicians in the 10th century which probably occurred at certain times of the day. Over time, nauba became a particular genre of music . This is the name given to the music played by the caliph's military orchestra at the five times of daily prayer ( salāt ).

According to the court chronicle Ain-i-Akbari of the Great Mughal Akbar , written by Abu 'l-Fazl around 1590 , his naqqāra-khāna consisted of 63 instruments. Two thirds of them were different drum types. In the list there are also 4 straight long trumpets karnā made of "gold, silver, brass or another metal", 3 further straight metal trumpets nafīr , 2 curved brass horns sings "in the shape of a cow horn", 9 cone oboes surnā (today in India shehnai ) and 3 pairs of hand cymbals (Arabic / Persian sanj ) mentioned.

The term karnā was no longer a curved metal trumpet, but - as is customary to this day - a straight metal trumpet. What a naubat ensemble looked like in the 17th century is shown in a miniature painting entitled "The Surrender of Kandahar", which is about the capture of the Mughal city of Kandahar by the Safavids in 1638. The miniature reproduced by Arthur Henry Fox Strangways (1914) shows five musicians with small pairs of kettle drums, four with cone oboes and four with long trumpets held at an angle in a pavilion. A musician seated in the middle with a medium-sized pair of kettle drums is probably the conductor. There is also a musician with a large standing kettle drum, one with a curved trumpet and a cymbal player. The trumpets are in three parts with spherical thickenings and end in long funnel-shaped bells. Three of the bells are broad, one funnel is narrow. A total of 18 musicians are shown, with one other person missing the musical instrument. A very early illustration of a short trumpet with such a thickening can be found on a relief at one of the Hindu temples of Khajuraho from the 12th century. The trumpet shown is probably a karna and belongs to the time of the Muslim conquests in northern India. Anthony Baines (1974) suspects the origin of this type of trumpet, which also spread westward with the Seljuks, among the metalworkers in Persia or Khorasan , the typical oriental thickening should probably give the trumpet a dignified appearance.

The explorer Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) reports on his stay in 1683/84 in the Safavid Empire during the reign of Shah Sulaiman . The Shah's ceremonial orchestra consisted of 40 musicians at the time and played every day at sunset and two hours before sunrise. Other occasions included religious holidays, royal banquets and the appearance of the new moon. In addition, the naqqāra-khāna was also increasingly used on less ceremonial occasions in everyday court life in connection with singers and dancers. In the 19th century the naqqāra-khāna in Tehran consisted of about 100 musicians and a dozen dancers. There, in Qazvin , Mashhad and Yazd , the naqqāra-khāna tradition survived until the late 1930s. In Mashhad, one of the two orchestras belonged to the Imam Reza Shrine and played in religious ceremonies in honor of ʿAlī ibn Mūsā ar-Ridā . The British contemporary witness Percy Sykes reported in 1909 about this naqqāra-khāna , whose musicians inherited their membership. The karnā consisted of 1.5 meter long cylindrical tubes made of brass or copper with two spherical knots and wide, funnel-shaped bells. In the orchestra of the shrine ten karnā , three cone oboes surnā and five kettle drum pairs played naqqāra .

distribution

Ceremonial long trumpets from the Arab-Persian musical culture are now common in India, Central Asia and Iran as well as in Islamic North Africa, for example as nafīr in Morocco and kakaki among the Hausa in northern Nigeria. The narrow and extremely long kakaki corresponds in shape to the Central Asian karnai and was introduced with the spread of Islamic culture in the western Sudan region from the north through the Sahara, up the Nile from Sudan or from the east African coast.

Iran

After the disappearance of the naqqāra-khāna , a karnā , also called derāz nāy ("long reed "), called a trumpet is still used in the ritual drama Taʿziye , which Shiites perform for Imam Husain , who is revered as a martyr . Every year in the mourning month of Muharram, theatrical means are used to publicly perform the events that led to Hussain's death in 680 as an element of the Shiite mourning ceremonies . The ritual theater has been known for over a millennium and received its approximate current form in the middle of the 18th century. The two opposing parties - Husain and the Alides against the Umayyad caliph Yazid I - can be distinguished by the colors of their costumes and the different singing style with which they recite their verses. The singers are from the cylinder drum dammam , the trumpet Karna , the reed flute ney and big clash cymbals zang brass accompanied. The karnā in this case consists of a 1.8 to 2.4 meter long bamboo tube with a cow horn as a bell. In the province of Gilan and in parts of the neighboring province of Māzandarān , an ensemble with ten long karnā trumpets performs at the Taʿziye performance .

The funeral ceremonies also include a procession in which men hit their chests with their fists ( sineh-zani ), accompanied by cymbals, and occasionally drums and trumpets. In Mashhad there is a funeral procession around the Ima Reza shrine. In Buschehr such a procession in every neighborhood positioned and of a band of eight cylindrical drums dammam , eight pools Zang and a conical trumpet buq from plants tube with an animal horn at the lower end cited. When the bands meet, it is up to the trumpet players to coordinate the rhythm.

The name karnā went over to a 90 centimeter long bowling oboe, which is used in regional folk music, among the Turkic-speaking Qashqai people and the Bakhtiarians in southern Iran. The wind instrument with double reed consists of a conical playing tube made of wood with usually seven finger holes and a thumb hole, at the lower end of which a brass bell, removed from a long trumpet karnā , was attached. The unwieldy trumpet should be made easier to transport and easier to play. This karnā is used with a cylinder drum dohol as an alternative to the smaller double-reed instrument sornā or together with it at funerals.

India and Nepal

Animal horns, which are among the oldest trumpet instruments, and long trumpets can be traced back to the Vedic period in India . Since the creation of the Rigveda , probably in the 2nd millennium BC According to this, horns were used in religious rituals. The Sanskrit word bakura , which occurs twice in the Rigveda in connection with gods , is interpreted as a wind instrument (horn or trumpet) and presumably as a snail horn. In any case, the bakura seems to have been a loud wind instrument that was used in war. Curt Sachs quotes a sentence from the Rigveda in his Reallexikon from 1913: "Blowing the Bakura at the enemy, they (the Açvin ) gave the Aryan people great shine". The snail horn has been known with the Sanskrit name shankha since the Middle Vedic period (beginning of the 1st millennium BC) . At the turn of the century, snail horns appear on reliefs on Buddhist stupas . According to the mythological texts, they were primarily used for religious rituals and also as military trumpets. The divine heroes portrayed in the Indian epic Mahabharata drowned out the war cries during the battles, each blowing his own horn. In the music-theoretical work Natyashastra, which was written around the turn of the times, another trumpet instrument is called tundakini in addition to shankha . On a relief from the 1st century BC The musicians and visitors depicted at Stupa 1 by Sanchi are recognizable by their clothing and unusual musical instruments as strangers who have made a long journey to the ceremony taking place here and apparently came from the west or perhaps belonged to the Gandhara culture . On the left edge of the lower row of images, two musicians blow long straight metal trumpets, which they hold up almost vertically with their heads tilted backwards. Instead of a bell, the trumpets end, as in the Celtic carnyx, in animal heads hanging downwards and the double wind instrument of the musician standing next to it is reminiscent of the ancient Greek aulos . The name karna and in many ways the ceremonial use of today's straight long trumpet in northern India are based on the medieval Arab-Persian culture. To what extent the ancient Indian trumpet instruments are forerunners of today's can hardly be clarified. At least the ensemble at the Sanchi stupa appears, according to the composition of the musical instruments and its function, as a forerunner of the later naubat , even if the shape of the instruments was different. In Sarngadeva's medieval music theory work Sangitaratnakara from the 13th century, tundakini is a 90 centimeter long straight trumpet, which the people call turuturi or tittiri . A trumpet twice as long is called a cukka . The ten wind instruments mentioned in the Sangitaratnakara also include kahala (metal trumpet made of bronze, silver or gold), shringa (curved metal trumpet), madhukari (equivalent to mohori , cone oboe) and murali ( bansuri , flute).

The three traditional trumpet types, which are common in India and Nepal and are divided into straight, semicircular and S-shaped bent according to their shape, have a narrow blowing opening with or without a mouthpiece and a tube that is slightly conical along its entire length. Long trumpets are used in India exclusively in religious and ceremonial music. The Arabic-Persian name karnā , also Hindi , Marathi and Tamil , is connected with Sanskrit and Bengali karanā .

In the north Indian state of Himachal Pradesh and in Nepal , the karnal ( Nepali कर्नाल) is a two-part telescopic brass trumpet about 137 centimeters long with a mouthpiece and a funnel-shaped bell that is used in folk music, temple rituals and processions. The Annapurna karnal , which is played in central Nepal, has a broadly flared bell , which in the Kalasha karnal is bowl-shaped. The integrated bowl mouthpiece is three centimeters in diameter. The karnal is played individually or in pairs by musicians from the Damai professional caste and belongs to the pancai baja ensemble. The pancai baja ensemble (also panche baja, "five musical instruments") is required for ceremonial music and consists of five musicians with cone oboes, barrel drums, small kettle drums, cymbals, curved and straight trumpets.

The karnal is similar to the bhankora , which is mainly used in the Garhwal region in the state of Uttarakhand for ceremonies such as weddings and at Hindu temples. In Nepal, the karnal made of copper or brass is also called ponga ( pãytā or pvangā ). Among other things, five pairs of ponga together with several drums are used as desikhin ( two-skin barrel drum struck with the hands, similar to the pashchima ) and cymbals to accompany a ritual dance at religious festivals of the Newar in the Kathmandu valley . According to a report from 1952, karna played in pairs were part of all religious or official ceremonies in Nepal.

Ballinger and Bajracharya (1960) differentiate between four straight metal trumpets in Nepal according to their shape and use through different boxes: The ponga is therefore a long straight copper trumpet , which consists of six parts and always in pairs and usually with the double-headed cylinder drum dhyamaya , the bronze cymbals bhusya and the blown bronze plate tainai with a stick . The slightly conical tube of the ponga is so thin and fragile that the player has to support it from below with a stick tied in the front third and held in one hand. The more conical copper trumpet paita is put together from five segments. In processions and religious ceremonies, five paita always play together with the pair of drums kotah , the cymbals taa and the small bronze cymbals babhu . The kaha is a pair of copper trumpets over 1.8 meters long, similar to the ponga. Players of these two trumpets precede religious and social processions. At funerals, the kaha is played with the double-headed cylinder drum nayekhin . The kaha belongs to the music of the Jyapu caste of Lalitpur (Patan), while the ponga is played by the Jyapu and Manandhar caste in Kathmandu .

The karna trumpet type is called dungchen or thunchen in Tibetan music . The dungchen is a 1.6 to over 3 meter long, artistically decorated trumpet made of copper and silver with a conical tube made of several telescopic parts and a wide bell, which is usually played in pairs in Tibet, Ladakh and Bhutan during Tibetan Buddhist rituals . According to the tradition of the Tibetan monasteries, the dungchen are blown at sunrise and sunset, at the beginning of a religious ritual and on the arrival or departure of important lamas . As soon as one player needs a break, the other kicks in, so that a constant drone sounds constantly . The conical trumpets in the Himalayan region can be clearly distinguished from the Chinese natural trumpets. In China, the la-ba is a slim, cylindrical or slightly conical metal trumpet with a small bell, which can sometimes be bent backwards by 90 degrees and only blows the second partial. The name la-ba has a Central Asian origin, which, according to Curt Sachs, refers to the origin of this trumpet from Mongolia and Tibet. It was used in the military and at wedding celebrations in the middle of the 20th century. The hao (or hau-tung ), also known by the military as a signaling instrument with a sound, has a wide, almost cylindrical bell at the lower end of its thin tube. This can be removed for transport. The wide conical trumpets of the Tibetan highlands were not adopted in China.

Other names for straight metal trumpets in northern India that were already known in ancient Indian times are kahala and turahi . Long straight trumpets have been depicted in the Ajanta caves since the beginning of the 1st millennium , easily recognizable on a relief on the sun temple of Konarak (around 1250). The Oraon, an Adivasi group in Bihar , use the almost 105 centimeter long cylindrical copper trumpet bhenr . In Rajasthan, the two-part straight bronze trumpet bhungal and the similar turhi are played in processions, especially at weddings. The two-part karna in Rajasthan and the one-part karnat in Gujarat have a wider, plate-shaped bell . Remnants of the representative orchestras in the Mughal period still exist as a simple naubat ensemble with the pair of kettle drums nagara and the cone oboe shehnai at a few Muslim shrines in Rajasthan, including the tomb of the Sufi saint Muinuddin Chishti in Ajmer . If large kettle drums and long trumpets are still kept there, they are rarely used.

A straight cylindrical long trumpet in South India is the tirucinnam used in Tamil Nadu for Hindu temple ceremonies, with a length of 75 centimeters, which is unique because it is blown in pairs by a musician with a difficult playing technique. From the first half of the 1st millennium, long trumpets came with Indian culture to the Malay Islands by sea . On the Indonesian island of Java , an unusual relief at the Candi Jawi (Jawi Temple) from the 13th century depicts a musician who holds two trumpets like the tirucinnam to his mouth and blows them at an angle. A longer cylindrical metal trumpet with a bell in Tamil Nadu is the ekkalam , which is used in temple processions. The gowri kalam , also used in temple processions in Tamil Nadu, has a three-part conical tube, a disc-shaped bell and a mouthpiece. P. Sambamurthy (1959) mentions in his Dictionary of South Indian Music and Musicians under the name karnā a 1.8 meter long conical brass trumpet made of two telescopic tubes and a bell-shaped bell, which is used at the Tyagaraja temple in Tiruvarur . The tube diameter is 2.5 centimeters at the air inlet and 7.5 centimeters at the lower end. At the upper end a small blow-in pipe is inserted and soldered on.

Turya, tuturi and bhuri are also called the single-wind trumpets, which are mainly played on ritual occasions and correspond to the European signal trumpet (field trumpet, clairon ) used in the 15th century . A Clairon also resembles the bronze trumpet bankia played in processions in Rajasthan. Curt Sachs (1923) rules out any European influence on these single-wind Indian trumpets. The most widespread ceremonial trumpets in India are conical, curved in a semicircle or S-shape and are called kombu in South India and ranshringa in North India .

Central Asia

The metal trumpets karnai ( karnaj or karnay ) that occur in Uzbek and Tajik music are predominantly cylindrical, up to three meters long and have thickenings at the joints between the tubes. The upper part of the tube appears cylindrical from the outside, but inside there is a conical tube which ends at a half-shell inserted into the tube end as a mouthpiece. The karnai is indispensable for the ceremonial wedding music . An ensemble typically consists of two trumpets and several cylinder drums , alternatively of one or more trumpets, cone oboes ( sornai ) and frame drums ( doira ).

The wedding chapels emerged from the former military orchestras. In the 19th century, loudly sounding instruments were used in Uzbekistan for official state ceremonies and outdoor military occasions: the karnay , the cone oboe sornay , the small cylindrical double-reed instrument baliman ( bulaman ), the kettle drum naghora and the frame drum doira. An early depiction of long ceremonial trumpets in Central Asia is on a gold-plated silver bowl from the 6th / 7th centuries. Century, which was excavated in the village of Bolshaya Anikowka in the Perm region in Russia ("Anikowo bowl"). The bowl probably comes from Khorezmia and represents an episode from the life of the mythical hero Siyawasch , who in Khorezmia is considered to be the progenitor of the Siyavuschiden-Afrighiden who lived from the 13th to the 10th century BC Should have ruled. In the center of the bowl seven trumpet players can be seen, dressed like soldiers, who hold their instruments straight up. The trumpets may have been in two parts and, in terms of form and function, represent forerunners of the karnai .

literature

- Anthony Baines: Brass Instruments. Their History and Development. Faber & Faber, London 1976

- Stephen Blum: Karnā. In: Encyclopædia Iranica , April 24, 2012

- Joachim Braun: Music in Ancient Israel / Palestine. Archaeological, Written, and Comparative Sources. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan 2002

- Ann Katharine Swynford Lambton: Naķķāra Khāna. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition , Vol. 7, Brill, Leiden 1993, pp. 927b-930a

- Henry George Farmer : Islam. ( Heinrich Besseler , Max Schneider (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume III: Music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1966

- Henry George Farmer: Būķ. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition , Volume 1, 1960, pp. 1290b-1292a

- Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975

- Tanya Merchant: Karnā. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Volume 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, pp. 115f

Web links

- Jazz Uzbekistan Style. Youtube video (two karnay blowers in front of a hotel entrance in Tashkent , Uzbekistan)

- Karnal (instrument). Youtube video (ceremonial ensemble with several carnals and large kettle drums in Himachal Pradesh )

- अती नै राम्रो पञ्चे बाजा by Lali Budhathoki / Dipak basanta Karki. Youtube Video (first details of a wedding in Nepal with a pancai Baja ensemble. Melodic is dominant, the bent double reed mohali , the trumpets karnal are heard only occasionally with a sound.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alfons Michael Duration : Tradition of African Wind Orchestras and the Origin of Jazz. (Contributions to Jazz Research, Vol. 7) Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1985, p. 45

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, p. 45

- ↑ Timkehet Teffera: Aerophone in the instruments of the peoples of East Africa. (Habilitation thesis) Trafo Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2009, p. 303f

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, p. 41

- ^ Anthony Baines (1976), pp. 49, 52

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse, 1975, p. 816

- ↑ Bo Lawergren: Iran. I. Pre-Islamic. 2nd 3rd millennium bce. (iii) Trumpets. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid: Mesopotamia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1984, p. 60

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse, 1975, pp. 746f

- ↑ Hans Hickmann: Egypt. ( Heinrich Besseler , Max Schneider (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 1) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1961, p. 40

- ↑ Hans Hickmann, 1961, p. 74

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2001, p. 11

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2002, p. 14

- ^ David Wulstan: The Sounding of the Shofar. In: The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 26, May 1973, pp. 29-46, here p. 30

- ^ Percival R. Kirby , Trumpets of Tut-Ankh-Amen and Their Successors. In: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Volume 77, No. 1, 1947, pp. 33-45, here pp. 35, 37

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2002, pp. 93, 181

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2002, pp. 205–207

- ^ Hans Hickmann: Horn instruments. B. Early history, orient and antiquity. In: Friedrich Blume (Hrsg.): The music in history and present , 1st edition, Volume 6, 1957, Col. 733

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1960, p. 1290b

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu: Musical Instruments of the Bible. Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2002, pp. 56f

- ↑ Joachim Braun: The music culture of old Israel / Palestine: Studies on archaeological, written and comparative sources. (= Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History ). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 47

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu, 2002, p. 94

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2002, pp. 32–34

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid: Mesopotamia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1984, p. 124, 160

- ↑ Cf. John Ziolkowski: The Roman Bucina: A Distinct Musical Instrument? In: Historic Brass Society Journal, Vol. 14, 2002, pp. 31-58, here p. 44

- ↑ Joachim Braun, 2002, p. 292f

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. A complete, authoritative encyclopedia of instruments throughout the world . Country Life Limited, London 1966, p. 68, sv “Buccina”

- ^ A b Edward H. Tarr: Trumpet. 4. The Western Trumpet. (ii) History to 1500. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Henry George Farmer: The Instruments of Music on the Ṭāq-i Bustān Bas-Reliefs. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 3, July 1938, pp. 397-412, here pp. 404f

- ^ A b Henry George Farmer, 1960, p. 1291b

- ↑ Bruce P. Gleason: Cavalry Trumpet and Kettledrum Practice from the Time of the Celts and Romans to the Renaissance. In: The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 61, April 2008, pp. 231-239, 251, here pp. 231f

- ^ Heinrich Hüschen: Isidore of Seville. In: Friedrich Blume (Ed.): Music in history and present, 1st edition, Volume 6, 1957, Col. 1438, plate 64

- ^ Curt Sachs : Handbook of musical instrumentation. (1930) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1967, pp. 282f

- ^ Anthony Baines (1976), p. 73

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1960, p. 1291a

- ^ Henry George Farmer: A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac & Co., London 1929, p. 154

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1929, pp. 208, 210

- ↑ Christian Poche: buq. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Henry George Farmer (1966), p. 52

- ↑ See F. Mücke Göçek: Nefīr. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition, Volume 8, 1995, p. 3b

- ↑ Michael Pirker: Nafīr . In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Henry George Farmer, 1966, pp. 76-78

- ^ Henry George Farmer (1966), p. 84

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Turkish Instruments of Music in the Seventeenth Century. As described in the Siyāḥat nāma of Ewliyā Chelebī . Civic Press, Glasgow 1937; Unchanged reprint: Longwood Press, Portland, Maine 1976, p. 30

- ↑ Henry George Farmer: Ṭabl-Khāna . In: Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition , Volume 10, 2000, p. 35b

- ↑ Ann Katharine Swynford Lambton, 1993, p. 928a

- ^ Henry George Farmer (1966), p. 116

- ↑ Alastair Dick: Nagara. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Henry George Farmer: A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac & Co., London 1929, pp. 153f; see. an-nūba, a major form of Arabic-Andalusian music

- ^ Reis Flora: Styles of the Śahnāī in Recent Decades: From naubat to gāyakī ang. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music , Vol. 27, 1995, pp. 52-75, here p. 56

- ^ Arthur Henry Fox Strangways: The Music of Hindostan. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1914, plate 6 on p. 77

- ^ Anthony Baines: The Evolution of Trumpet Music up to Fantini. In: Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 101, 1974-1975, pp. 1-9, here p. 3f

- ↑ Anthony Baines, 1976, pp. 75f

- ↑ Ann Katharine Swynford Lambton, 1993, pp. 928b, 929

- ^ P. Molesworth Sykes : Notes on Musical Instruments in Khorasan, with Special Reference to the Gypsies . In: Man , Vol. 9, 1909, pp. 161-164, here p. 163

- ↑ See KA Gourlay: Long Trumpets of Northern Nigeria - In History and Today. In: Journal of International Library of African Music, Vol. 6, No. 2, 1982, pp. 48-72

- ↑ Deraz-Nay . Photo-Encyclopedia Persica (illustration)

- ^ P. Chelkowski: Taʿziya . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition , Volume 10, 2000, pp. 406b-408b, here p. 407a

- ↑ Stephen Blum: Iran III: Ritual and popular traditions. Islamic. 2. Ritual and ceremony. (ii) Nowheh. In: Stanley Sadie (Ed.): New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 12, 2001, pp. 538f ( Grove Music Online, 2001)

- ^ Jean Jenkins, Poul Rovsing Olsen: Music and Musical Instruments in the World of Islam. Horniman Museum, London 1976, p. 68

- ↑ Stephen Blum, Encyclopædia Iranica , 2012

- ↑ Alastair Dick: Bákura . In: Grove Music Online , September 3, 2014

- ^ Curt Sachs: The History of Musical Instruments . WW Norton & Co., New York 1940, p. 152

- ^ Curt Sachs: Real Lexicon of Musical Instruments. Julius Bard, Berlin 1913, p. 27b, sv "Bákura"

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu: The Conch Horn. Shell Trumpets of the World from Prehistory to Today. Hataf Segol Publications, 2018, p. 55

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume 2. Ancient Music . Delivery 8. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, p. 34

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann, 1981, pp. 62, 64

- ^ Alastair Dick: The Earlier History of the Shawm in India. In: The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 37, March 1984, pp. 80-98, here pp. 84f

- ^ Curt Sachs: The musical instruments of India and Indonesia. At the same time an introduction to instrument science. (2nd edition 1923) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1983, p. 171

- ^ Gert-Matthias Wegner, Simone Bailey: Karnāl . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Volume 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 116

- ↑ Richard Widdess, Gert-Matthias Wegner: Nepal, Kingdom of. I. Music in the Kathmandu Valley. 2. Newar music. (ii) Castes, genres and instruments. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ^ Alain Daniélou : South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, pp. 80, 82

- ^ Thomas O. Ballinger, Purna Harsha Bajracharya: Nepalese Musical Instruments. In: Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 16, No. 4, Winter 1960, pp. 398-416, here pp. 403, 405-407

- ↑ Alain Daniélou, 1978, p. 84

- ^ Curt Sachs leads (in: The History of Musical Instruments . WW Norton & Co., New York 1940, p. 210) back la-pa like Japanese rapa to Mongolian rapal . In contrast, Bertold Laufer holds (in: Bird divination among the Tibetans. In: Henri Cordier, Edouard Chavannes (Ed.): T'oung Pao, Volume 15, EJ Brill, Leiden 1914, pp. 1–110, here p. 90 ) la-pa for neither Tibetan nor Mongolian, but refers to a list of musical instruments in Turkestan published in 1772 .

- ^ Kurt Reinhard : Chinese Music . Erich Röth, Kassel 1956, p. 127f

- ↑ Curt Sachs, 1940, p. 210; see. Sibyl Marcuse: Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. A complete, authoritative encyclopedia of instruments throughout the world . Country Life Limited, London 1966, p. 475, sv “Siao t'ung kyo”

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: Musical Instruments of India. Their History and Development . KLM Private Limited, Calcutta 1978, p. 111f

- ↑ RAM Charndrakausika: Naubat of Ajmer . Saxinian Folkways

- ^ Reis Flora: Styles of the Śahnāī in Recent Decades: From naubat to gāyakī ang. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music, Vol. 27, 1995, pp. 52-75, here p. 57

- ^ Jaap Art : Hindu-Javanese Musical Instruments. (1927 in Dutch) Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag 1968, p. 32

- ^ S. Krishnaswami: Musical Instruments of India. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, New Delhi 1965, p. 90

- ^ Museum of Performing Arts. Gallery of Musical Instruments. Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi n.d., p. 18

- ↑ P. Sambamurthy: A Dictionary of South Indian Music and Musicians. Volume 2 (G – K), 1959, 2nd edition: The Indian Music Publishing House, Madras 1984, p. 365, sv "Karnā"

- ^ Curt Sachs: The musical instruments of India and Indonesia. At the same time an introduction to instrument science. (2nd edition 1923) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1983, p. 171

- ↑ Laurence Libin: Kamay. In: Grove Music Online , May 28, 2015

- ^ Anthony Baines, 1976, p. 76

- ^ Razia Sultanova: Uzbekistan. 3. Musical instruments. (i) Court traditions. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ FM Karomatov, VA Meškeris, TS Vyzgo: Central Asia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume II: Music of antiquity . Delivery 9) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1987, p. 158