The death of Marat

|

| The death of Marat |

|---|

| Jacques-Louis David , 1793 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 162 × 128 cm |

| Royal Museums of Fine Arts , Brussels |

The Death of Marat is a painting by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825). It was painted in the classical style in oil on canvas in the summer and autumn of 1793 and measures 162 by 128 cm. It is one of the most famous depictions of the events of the French Revolution .

Image description

The picture shows the dying Jean Paul Marat as a muscular naked man: He is lying in a bathtub , his hair covered in a kind of turban , the puncture wound can be seen in the shadow below his collarbone . The bath water is red with blood, the murder weapon, a knife, lies in front of the tub. In his right hand he is holding a quill and in his left hand is a letter on which the words can be read:

«Du 13 juillet, 1793 / Marieanne Charlotte Corday au citoyen Marat. II suffit que je sois bien malheureuse pour avoir droit à vre bienveillance. »

"13. July 1793. Marieanne Charlotte Corday to the citizen Marat. That I am very unhappy is enough to have a right to your benevolence. "

On the tub is a table top with papers, next to it a simple wooden box on which the painter's dedication can be read in capital letters : “À Marat, David.” (“For Marat, David.”) With an inkwell, an assignat and another letter in which you can read:

«Vous donnerez cet assignat à la mère de cinq enfants dont le mari est mort pour la defense de la patrie. »

"Would you give these assignats to the mother of five children whose husband died for the fatherland."

The background doesn't show any details and is rather dark; it becomes lighter towards the top right. The composition of the picture is strictly classical. The picture gets a tension through the contradiction that a murdered man is shown, but who still has the strength in his hands to hold pen and paper, and whose head has not yet sagged backwards or forwards. David obviously tried to show Marat at the moment of death.

background

Jean Paul Marat (1743–1793) was originally a doctor, journalist, member of the Club des Cordeliers and later also of the Jacobin Club , and from August 1792 a member of the National Convention . Due to a skin condition he allegedly contracted while hiding from his opponents in the Paris sewers, he had to rely on cool baths to relieve symptoms for the last three years of his life. A 2019 study suggests that Marat's disease was seborrheic dermatitis . Because of an aggravation of his suffering he hardly took part in the parliamentary sessions since June 1793, but remained active as a journalist. In his newspaper, L'Ami du Peuple , he repeatedly called for vigilance against traitors, conspirators and so-called enemies of the people. In doing so, he contributed at least indirectly to various revolutionary acts of violence, such as the September massacres in 1792 or the persecution of the Girondins after their overthrow in June 1793. The Girondist General Felix von Wimpffen , who opposed the National Convention in the summer of 1793 and occupied Caen , he described it as "le plus vil des hommes" - "the meanest of people".

The unmarried noblewoman Charlotte Corday, who was close to the Girondins, lived in Caen. Under the influence of the Girondist press, which was widespread there, she believed Marat to be the originator of the terror that she experienced. She decided to go to Paris and murder him in the convent. Arrived on July 11, 1793, she learned that Marat was no longer attending the convent meetings. So she tried to see him in his apartment on rue des Cordeliers (now rue de l'École de Médecine ). For this purpose she wrote a letter to Marat that ended with the words quoted in the painting. She was turned away twice, the third time she pushed her way into the apartment with an employee. Marat was startled in his bathtub by the noise made by the attempts to throw her out and asked his partner Simone Evrard to bring Corday to him. Without giving him the letter, she engaged him in a conversation about the rebellion in Normandy. When Marat said he would "have everyone guillotine in a few days ," she stabbed. Marat called for help, one of his employees knocked Corday down with a chair, she was taken away tied up and executed a few days later. During her first interrogation, she confessed to the deed that she had planned and carried out on her own in order to free France from civil war:

"Persuadée que Marat était le principal author de ce désastre, elle avait préféré à faire le sacrifice de sa vie pour sauver son pays. »

"Convinced that Marat was the main cause of this disaster, she preferred to sacrifice her life to save her country."

Marat was lifted out of the bathtub alive and laid on his bed, where he died soon after of the stab wound in the chest.

Emergence

Immediately after Marat's death, a real cult began around him in the Parisian city population , which was skillfully staged by Marat's friend, the member of the National Convention and painter Jacques-Louis David. The painting was also created in this context. Immediately after the news of Marat's death in the National Convention, David was asked to do so by the deputy François-Elie Guiraut on July 14, 1793: He asked him to create a counterpart to his recently painted picture “Les derniers moments de Michel Le Peletier ” ( “The last moments of Michel Le Peletier”). Thereupon David immortalized the death of Le Peletiers who, because he had voted for the execution of the king, had been murdered by a royalist officer in January 1793 . David painted him dying on his death bed, above him, hung by his hair, a sword with a piece of paper that read: “Je vote la mort du tyran” (“I vote for the death of the tyrant”). This picture is lost today, there is only an incomplete copy in the form of a copper engraving by Pierre Alexandre Tardieu .

David completed his painting in three months. On October 16, both pictures were presented to the Parisians in the Cour carrée of the Louvre , and on November 14, he presented the finished death of Marat to the convention. He decided to hang both pictures on the front of the boardroom in the Palais Bourbon .

interpretation

David idealizes Marat as a martyr of the revolution. The fact that he was the victim of an assassination attempt without his own involvement is reinterpreted in his painting as an active self-sacrifice. The murderess cannot be seen in the picture, only the letter (which Marat never actually received), the stab wound and the knife indicate her presence. The similarity to Michelangelo's Pietà or Caravaggio's The Entombment of Christ - for example the arms hanging down - is certainly not accidental. Other well-known artists such as Peter Paul Rubens and Guy François also used this style element . The representation of the revolutionary in the pose and lighting of a Christian martyr, if not a Christ , transferred the imagery of the monarchy and the Catholic faith to the new French republic.

The fact that David does not depict Marat's skin disease, instead, Marat's body is classically beautiful, bathed in a milky light, also contributes to the idealization. The simplicity of the painting is in harmony with the promised virtues of Marat, which is still certified by the generous donation to the large war widow. The dominant dark background is used by David as an element increasing meaning and emphasizing the emptiness that has been left behind.

What concrete propaganda intentions David pursued with the picture, which was widely distributed as an engraving in ten thousand copies, is controversial. Jörg Traeger sees a connection with the campaign for the new constitution , which was passed on June 24th, 1793 and approved by the French with a large majority in a referendum on August 10th, 1793 . Thomas W. Gaehtgens, on the other hand, believes that with the painting David wanted to call on the French to defend themselves against internal enemies, as they had become visible in the attacks on Le Peletier and Marat. In this interpretation, The Death of Marat would be a call to the Great Terror that officially began on September 5, 1793.

Afterlife

After Robespierre's fall, the painting was removed from the Palais Bourbon and David had to keep it hidden for years to prevent destruction. Subsequent French governments refused to buy the picture twice (1826 and 1837); a nephew of David bequeathed it to the Royal Museum in Brussels in 1893 , where the painter had also spent his old age.

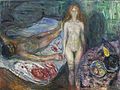

The picture, an icon of the French Revolution, was received many times by other painters. David's contemporary Guillaume-Joseph Roques (1757–1847) created a death of Marat in 1793 , which is clearly based on David and seeks to surpass him: his portrayal of a dead person is more realistic - the head is sagging, the eyes are broken The hand can no longer hold the pen - the room has a lot more details, the wound and the blood are painted more drastically. Instead of idealization, it is about painting the horrific happenings. The history painter Paul Baudry (1828–1886) portrayed the event in a completely different way in his painting The Assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday , which was created in 1861 at the time of the Second German Empire : Here, the focus is on the assassin, she is the heroine who courageously brought down the murderous beast of the revolution - for France , which dominates the background of the picture in the form of a map. Less than twenty years later, Jean-Joseph Weerts (1847–1927) presented the event at the time of the Third Republic in 1880 from a patriotic-republican perspective: Corday is a terrorist murderer here. She stands, the bloody knife still in her hand, facing the angry, hysterically gesticulating crowd of revolutionaries who suddenly enter the room. The dying Marat has moved to the lower edge of the center of the picture, a reference to David's work can no longer be recognized. The Mexican painter Santiago Rebull Gordillo (1829–1902) also romanticizes and dramatizes the events in his work La muerte de Marat , created in 1875 : Marat rears up, Corday snatches the dagger, in the background the horrified servants rush into the room. A political statement can no longer be made out here. The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) eroticized the murder in his 1907 painting Marat's Death : He shows Corday standing naked on the bed in front of the likewise naked Marat, a parable of the “cruel, existential gender struggle”.

Edvard Munch: Marat's Death I (1907)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Also on the following Thomas W. Gaehtgens , Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 193 f.

- ^ Toni de-Dios, Lucy van Dorp, Philippe Charlier, Sofia Morfopoulou, Esther Lizano: Metagenomic analysis of a blood stain from the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1793) . In: bioRxiv . October 31, 2019, bioRxiv : 10.1101 / 825034v1 ( preprint full text), p. 825034 , doi : 10.1101 / 825034 .

- ↑ a b Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 188.

- ↑ Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 195 ff.

- ↑ Jörg Traeger: The death of the Marat. Revolution in the image of man . Prestel, Munich 1986

- ↑ Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 195 ff.

- ↑ Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 194 f.

- ↑ "The Assassination of Marat" at mheu.org, accessed on January 23, 2011

- ↑ Edvard Munch, Tod des Marat I on edvard-munch.com, accessed on January 22, 2011

- ↑ Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, p. 206

literature

- Thomas W. Gaehtgens: Davids Marat (1793) or the dialectic of the victim . In: Alexander Demandt (ed.), The assassination in history . Area, Erfstadt 2003, pp. 187-213 ISBN 3-89996-001-7

- Antoine Schnapper: J.-L. David and his time . Edition Popp, Würzburg 1985, ISBN 3-88155-089-5 .

- Jörg Traeger: The death of Marat. Revolution in the image of man . Prestel, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-7913-0778-9 .

Web links

- Thomas Gransow, Sibylle Witting: Paris and Versailles. Musée National du Chateau de Versailles (Four texts on David's death of Marat )

- "The Assassination of Marat" on mheu.org