Tristan chord

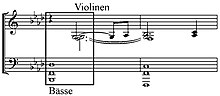

The Tristan chord is a " leitmotiv " used chord in Richard Wagner's music drama Tristan und Isolde, which premiered in 1865 . It is heard for the first time in the second bar of the prelude to Act I in the cellos and woodwinds, where it forms the end of the cello melody and the beginning of the oboe melody (NB 1). A variant sounds at the beginning of the III. Acts in the strings (NB 2).

Because of its harmonic opacity, the chord has eluded a simple or generally accepted interpretation to this day. There have always been very different attempts to interpret it functionally harmonious. Its ambiguity is also typical of the extremely chromatic and tonally inconsistent harmony of the Tristan score, in which Ernst Kurth saw a crisis in the romantic harmony.

Possible interpretations

Altered lead chord

The "g sharp 1 " is viewed as a lead that dissolves after "a 1 ", so that the actual chord is "fh-d flat 1 -a 1 ". This altered third fourth chord can in turn be interpreted differently:

- In terms of the degree theory , it can be interpreted as the second inversion of the seventh chord of the second degree of A minor (ie "hdfa") with a highly altered third (d → "dis").

- The function theory interprets it preferably as inverse shape of a double Dominant - seventh chord of a minor (ie, "h-dis-fis-a") with tiefalterierter fifth (fis → f) in the bass .

- The functional derivation of the subdominant triad with sixth ajoutée (ie “dfah”) is less common, whereby the chord root “d” is altered to “dis”.

The interpretation as a leading chord has the advantage that the dissolution chord fits easily into a cadence, but it was also often criticized because the dissolution has too little weight because of its short duration to be perceived as the main chord.

Altered chord without a lead

In this variant, the interpretation of "dis is 1 " "d as a high-alteration of the 1 construed", so that the original chord "FHD 1 -GIS 1 " is called. The diminished seventh chord “g sharp-hd 1 -f 1 ” results from the basic position in a narrow position , which according to the degree theory would be the seventh degree of A minor and according to the function theory a “shortened” dominant ninth chord (with missing root “e ").

Independent chord

Since the Tristan chord appears again and again in the course of the opera independently of the respective continuation and in different notations, there has been no lack of attempts to interpret the chord in the sense of a "leitmotif" as an independent sound structure (i.e. G sharp 1 as a chord tone, a 1 as passage):

- One possibility is to interpret it as a double minor tone of E major. This arises from the fact that in the E major triad the root key e is replaced by its upper (f) and lower (dis → dis 1 ) leading tone . However, D 1 1 is not resolved upwards into the expected root e 1 , but rather led downwards into the seventh d 1 of the target sound E 7 . Although this interpretation takes into account the tonal context at the beginning of the prelude, it cannot simply be transferred to the other manifestations of the Tristan chord.

- Another interpretation is based on Vogel's clay net . According to the Riemann Musiklexikon, "the interpretation as a sub-septime sound with the inclusion of the natural septime (Hancer, Vogel ) enables a uniform understanding of the sound in its changing spellings and connections, but it does nothing for the understanding of the tonal relationships."

- By Paul Hindemith his will according to the rules instruction in music theory determined "gis" as the root of the Tristan chord. In accordance with the newly developed chord theory , according to which all chords can be clearly identified, he assigns it to group "II b2 " of his table of chords . He defines A as the tonic (“tonal center”) of the entire passage (without the addition of “major” or “minor”). Hindemith's analysis of Tristan in this music-theoretical work published in 1937 has so far played a marginal role in the discussion on Tristan that has been going on since 1879, because Hindemith's system has been heavily criticized for some inconsistencies in the derivation of its rules. However, at the time of its publication, insights emerged from it that other musicologists only published decades later.

Non-independent chord

New aspects arise when the Tristan chord is viewed as part of cadenced contexts. Peter Petersen 2019: "In general, we have to get away from piecework analysis and finally have to do cadence analysis." In Act I m. 1–3 the chord is connected to a chromatic motif ( g sharp 1 -a 1 -ais 1 -h 1 ) (NB 1), which gives it a special color, in III. Act m. 1–2 has a normal minor color because it harmonizes a diatonic motif (g-a-flat-bc 1 ) (NB 2). Depending on the context, two types of Tristan chords can be distinguished:

- the chromatic type (TA chr ) with altered tones (f / h / dis 1 / g sharp 1 ), cf. also the whole-tone following sounds (f / h / dis 1 / a 1 and e / g sharp / d 1 / ais 1 ). It is part of a semi-closed cadence that ends with a dominant seventh chord;

- the diatonic type (TA dia ) with its own ladder tones (Bb / des / f / g), see also the purely diatonic sequential sounds (Bb / des / f / as and F / c / g / b) It either belongs to a plagal cadenza with the sequence IV.–I. Degree, or it is integrated as a half diminished seventh chord in various cadence contexts (e.g. as a seventh chord of the second degree minor or the seventh degree major).

Looking at the opera as a whole, the TA chr can be assigned to Isolde's emotional world. The TA dia represents Tristan's love tendons, but also expresses the love of both together.

Musical historical significance

In view of the historical further development of the harmony, the creative and pioneering different developments of the Tristan chord in the course of the entire work as well as the embedding in the high-tension chromatic alteration style of the opera are particularly interesting . The chord often appears with the same pitches, but with enharmonic changes (e.g. “f, h, es, as” or “f, ces, es, as”) and in a different tonal and harmonic environment, which is what the analysis does the beginning additionally difficult. The Tristan chord is thus a kind of epitome of late romantic harmony, which since then has been losing more and more of its hold and binding force to the tonic , until it finally turns completely into atonality around 1910 .

It is also significant in terms of music history that the Tristan chord is characterized by its virtually non-existent strut effect. You don't hear it as a dominant with a sixth lead, since the resolution of the lead into the seventh is only heard as a chromatic passage (because this is only an eighth note). As a subdominant, however, it cannot convince either. So it initially stands in the room without any direction until the progression that leads to the dominant "E" reveals the tonal connection in A minor.

Another aspect that is often neglected in the Tristan discussion is the fact that not only does the Tristan chord in itself have no direction of resolution (that is what makes it ambiguous), but rather the dominant into which it ends, no more than a dissonance with an absolutely required resolution is heard. The listener perceives this dominant as a dissolution rather than a chord to be dissolved. What takes place here is what Arnold Schönberg later called the “emancipation of dissonance”, which in the early 20th century led to compositional styles in which dissonances no longer have any striving effects in the conventional sense.

The Tristan chord in other composers

The Tristan chord, also quoted by Wagner himself in the Meistersinger , is so well known in music theory that other musicians later quoted it.

Later quotations

- Edvard Grieg uses the chord (transposed to d-g sharp-his-eis', with a corresponding - but interrupted by g sharp '- leading resolution to f sharp') in one of his lyrical pieces ("Volksweise" op. 12 No. 5, bar 15 and 31, each on count time 3).

- Antonín Dvořák uses it in his Mass in D major op. 86 (Credo T. 219).

- Max Reger, Variations op. 73 for organ, final chord of the 9th variation

- Alexander Scriabin uses the chord several times in the first movement of his 4th piano sonata .

- Claude Debussy parodies him in his " Golliwog's Cakewalk ".

- Louis Vierne , 24 Pieces en style libre pour orgue, No. 10 Reverie, bars 5-7 and so on.

- Alban Berg quotes him in the last movement of the Lyric Suite and several times in crucial places in his opera Lulu .

- Benjamin Britten quotes him in his opera Albert Herring (hiccup scene in Act 2). In addition to its function as a pure quotation, the Tristan chord also has a symbolic meaning (complete disinhibition).

- Hanns Eisler uses it several times in his work.

Earlier occurrence

- The Tristan chord appears several times in Antonio Salieri's operas. For example, in bar 24 of the aria Son queste le speranze from the opera Axur, re d'Ormus (there, however, transposed: c-ges-b-es)

- In Joseph Haydn's String Quartet in C major Op. 54 No. 2 from 1788, the chord appears (albeit in a confused enharmonically fh-es-a-flat form) in the trio of the minuet (bars 66f.). Georg Feder describes it as "one of the most yearning chords that appear in Haydn's quartets".

- Even Beethoven used this chord enharmonically in his E-flat major Piano Sonata, Op 31 no. 3. 1802 in bars 35-42:

- In contrast to Wagner, the functional classification in a cadence does not cause any problems. It is a reverse form of the subdominant A flat minor triad with sixte ajoutée , which can be related to E flat minor as a tonic , which even appears in its original form at the beginning of the musical example. Beethoven treats the “es” of the chord as a dissonance and resolves it into “d”. However, since the dissolution chord is itself a dissonance chord (diminished seventh chord in the dominant function), there can be no question of a "dissolution" in the actual sense, especially since the tonic expected as the end of the cadence is missing. Beethoven lets this dissonance chord stand unresolved in the room four times, transposed twice to E flat minor and twice to F minor. This example shows that the “emancipation of dissonance” does not just begin with Wagner, although it is particularly strongly promoted by him.

- Franz Schubert's song That she was here D 775 was written around 1823. It starts with four transposed Tristan chords in inversion:

- The Tristan chords resolve into diminished seventh chords . This creates a tonal indeterminacy that lasts for 12 bars. The basic key of C major is only prepared in bar 13 by the dominant seventh chord and finally reached in bar 14. Another example of the “emancipation of dissonance” cited long before Wagner.

- Frédéric Chopin uses the chord (albeit with ice instead of f) in the exact position of his first appearance with Wagner as early as 1831 in his ballad No. 1 in G minor , bar 124.

- In Robert Schumann's Concerto for Violoncello Op. 129 from 1850, the identical chord appears with the following identical resolution in bar 11, divided between the solo cello and the orchestral parts.

literature

- Altug Ünlü : The 'Tristan chord' in the context of a traditional sequence formula. In: Music Theory. Musicology journal. Vol. 18, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 0177-4182 , pp. 179-185, ( digital version (PDF; 183.85 kB) ).

- Peter Petersen : Isolde and Tristan. On the musical identity of the main characters in Richard Wagner's "plot" Tristan and Isolde, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2019.

- Thomas Phleps : Traffic routes of the Tristan accord with Hanns Eisler. In: music contexts. Festschrift for Hanns-Werner Heister. Vol. 2. Ed. Thomas Phleps and Wieland Reich. Münster: Verlagshaus Monsenstein and Vannerdat 2011, pp. 713–724. [1]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. the chapter "Tristan Harmonics" in Peter Petersen : Isolde und Tristan. On the musical identity of the main characters in Richard Wagner's "plot" Tristan and Isolde, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2019, p. 47 ff.

- ^ Ernst Kurth: Romantic harmony and its crisis in Wagner's "Tristan". Haupt, Bern et al. 1920.

- ↑ a b Willibald Gurlitt , Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht (Ed.): Riemann Music Lexicon. Material part. 12th, completely revised edition. B. Schott's Sons, Mainz 1967, p. 987.

- ↑ Marc Honegger, Günther Massenkeil (ed.): The great lexicon of music. Volume 8: Štich - Zylis-Gara. Updated special edition. Herder, Freiburg (Breisgau) et al. 1987, ISBN 3-451-20948-9 , p. 168.

- ↑ Constantin Houy: Hindemiths analysis of Tristan foreplay. An apology. In: Hindemith yearbook. Vol. 37, 2008, ISSN 0172-956X , pp. 152-191.

- ↑ Peter Petersen: Isolde and Tristan. On the musical identity of the main characters in Richard Wagner's "plot" Tristan and Isolde, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2019, p. 17.

- ↑ See the chapter "Tristan Harmonics" in Peter Petersen: Isolde und Tristan. On the musical identity of the main characters in Richard Wagner's "plot" Tristan and Isolde, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2019, p. 47 ff.

- ^ Georg Feder: Haydn's string quartets. A musical work guide (= Beck'sche Reihe 2203 CH Beck Wissen ), Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43303-0 , p. 79.