Upstalsboom

The Upstalsboom ( Dutch Opstalboom , old Frisian Opstallisbaem ) was the meeting place for the delegates of the Frisian state communities, the Seven Zealand Lands , west of today's city of Aurich , during the period of Frisian freedom in the 13th and 14th centuries . There they regulated coexistence within the regional communities and represented the federal government externally. A stone pyramid has commemorated these gatherings since 1833 . In the time of National Socialism, the area was to be redesigned into a thing place . However, these plans were no longer implemented, so the appearance of the site has largely remained unchanged since 1879.

Today's owner of the area is the East Frisian landscape .

Name interpretation

The interpretation of the name is uncertain. It is also unclear since when the site has been named. Later interpretations started with the second part of the word “boom”, meaning tree. However, it does not necessarily have to be a plant. In this context, boom stands for a worked tree, i.e. a border tree, a barrier or a stake that may have stood on the hill to tie up the cattle. The word “Upstall” is of Flemish-Brabant origin and is translated as a fenced plot of land that the village community used as a common pasture area, as common land .

description

The site is an early medieval burial mound. Information that it is a prehistoric burial mound is based on false information in a museum catalog of the Society for Fine Art and Patriotic Antiquities in Emden . The highest point is 6.80 m. It is surrounded by a hedge landscape. The grave was erected on a ridge of sand, which was dammed up during the Saale Ice Age by glacier movements.

history

Previous use

Archaeological research suggests that the site has been used since the 8th century. It was probably residents of one or more of the surrounding courtyards who buried their dead on the site. Why the Frisians chose the hill as their meeting place is unclear. Its central location within the Frisian settlement area was possibly decisive. In addition, the place was easily accessible both by land and by water.

Frisian Diet

At the time of the Frisian Freedom, East Friesland was divided into autonomous state communities, which were headed not by nobles, but by Redjeven elected by the land and court owners . There was no bondage , but there was a dependency of the tenants on the landowners.

The Upstalsboom is first mentioned in the “Chronicle of the Bloemhof Monastery” from 1216. Representatives from the Frisian regional communities met there until the 14th century to speak up and pass resolutions. According to the Frisian Überküren, which probably originated in the 12th century, the meetings should take place once a year on the Tuesday after Pentecost . Each regional municipality was usually represented by two members. These were already chosen at Easter and called Redjeven. This was also regulated in the respective state law. This is what it says in the Emsiger law from around 1300:

“Thit send tha urkera allera Fresena. Theth forme, theth hia gaderkome enes a iera to Upstelesbame a tyesdey anda there pinxtera wika and ma ther eratta alle tha riucht, ther Fresa halda skolde. Jef aeng mon eng bethera wiste, theth ma the lichtere lette and ma theth bethere helde. "

Translated this means: “These are the overkings of all Frisians. Firstly, that they meet at Upstalsbom once a year on Tuesday in the week of Pentecost and that all rights that the Frisians should uphold will be discussed there. If anyone knew a better (right), one should give up the less right and obey the better. "

The first meeting is said to have taken place in the middle of the 12th century to settle disputes between the Wangerland and the Gau Östringen . This goes back to later traditions. There are no contemporary sources. There is documentary evidence of the meetings at the Upstalsboom between 1216 and 1231 and from 1323 to 1338. An Upstalsboom seal with a diameter of 12 cm was also created during this time . In 1323 the Upstalsboom Laws were passed , which adapted the old statutes of the time. This union was supposed to keep the peace between the individual Frisian areas. At their get-togethers, the Redjeven not only regulated coexistence within their national community, but also represented them politically to the outside world. The Landfriedensbund was an emergency community of the Frisian Freedom , but it soon collapsed. The last tradition about a Landtag of the Seven Seas comes from the year 1328, when the judges, counselors and communities gathered in Appingedam concluded a contract with the King of France. The next conference took place in Groningen in 1361 . However, the city's attempt to renew the covenant under her leadership was unsuccessful.

Further use

It was only in the struggle against absolutism that the Frisian will for freedom reawakened, and the Upstals boom gained new symbolic power. In 1678 Emperor Leopold I awarded the Upstalsboom coat of arms as a national emblem.

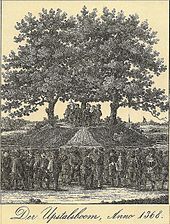

The area near Rahe, on the other hand, was largely forgotten. Local farmers continued to use it as community pasture. The earliest known description of the area is from Ubbo Emmius . He wrote in 1598: "There rise three huge oaks, one of which, almost dead, has survived to our time, with branches almost touching one another on open ground".

After the common land was divided, it came into the possession of several farmers (except for the actual hill). These enlarged their surrounding fields in the following period so that the Landdrostei in Aurich saw itself compelled to take action to protect the Upstalsboom in 1827. First, she had the area surveyed. It turned out that the farmers had illegally appropriated land around the hill, which was only about 33 meters long and 15 meters wide. The Landdrostei then suggested buying the land and building a cast iron pyramid on the hill. The authority asked the East Frisian estates to comment on this project. They opted for a stone pyramid and then began to buy up the lands around the hill from 1832. She later also received the hill, although it is still unclear when she bought it from the state or received it as a gift.

Monument and landscape park

The first considerations to erect a memorial on the hill were made in 1815. The Aurich architect Conrad Bernhard Meyer wanted to erect an obelisk on the site to commemorate the East Frisians who fell in the battles of Belle Alliance and Ligny during the wars of liberation . To finance this project, he set up a wooden model on the hill and made an engraving, the proceeds of which were to go towards the construction of the monument. However, this project failed due to the lack of participation by the East Frisians.

In 1833 the East Frisian Estates (today: East Frisian Landscape ) finally erected a stone pyramid. According to Conrad Bernhard Meyer's initiative, it commemorates the East Frisian soldiers who fell in the Wars of Liberation. Some of the field stones used for its construction come from the foundation of the Lambertikirche in Aurich , which was demolished at that time due to its dilapidation.

Immediately after completion of the monument, the site was given a surrounding ditch and a gardener planted the site mainly with oaks in the following two years. After 1879, the East Frisian landscape enlarged the park by purchasing more land up to today's country road. An avenue of beech trees was created on this property, which leads to the pyramid. In 1894, the landscape finally had a granite tablet attached to the pyramid. It bears the inscription: At the meeting place of your ancestors, the Upstalsboom, erected by the East Frisian estates in 1833 . After that, the appearance of the site did not change until the National Socialist era .

time of the nationalsocialism

In the Third Reich , the Upstals boom caught the eye of the new rulers early on. The area developed into an "ideal place for celebrations and marches". In addition, the National Socialists wanted to set up a thing site there. The landscape council was very cautious about this, but made the area available for events. From 1935 the idea was in the room to redesign the property according to the model of other National Socialist thing sites. The initiator was the Norderneyer hotel owner Johannes Campen, who wanted to perform his play Bauer Bertus und der Upstalsboom at the Upstalsboom . These plans were not implemented, nor was the suggestion made by the art warden of the East Frisian landscape, Dr. Louis Hahn to turn the site into a thing site. The landscape only provided little money with which the planting was changed somewhat. In addition, the area received a new entrance gate in 1937.

post war period

The area of the Upstalsboom hardly underwent any changes in the post-war years. Only the hill was topped up in 1969 with silt from the Aurich harbor. Otherwise, all measures are limited to landscape maintenance. Currently (as of 2013) there is an initiative to recognize the Upstalsboom as a national natural monument. This initiative expanded the application in September 2014 and is now committed to designating the area of the “Upstalsboom and the surrounding historical wall hedges” as a national nature document. The Lower Saxony Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Climate Protection (MU) as the responsible supreme nature conservation authority currently sees it as "appropriate, prior to a specific interpretation of the individual requirements, possibly at the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety and at the Federal Ministry of Transport and digital infrastructure to appreciate already developed ideas, since the declaration on the national natural monument is issued in consultation with the federal ministries concerned ”.

archeology

Conrad Bernhard Meyer discovered an urn while excavating a wooden scaffolding in 1815. This later provided the false information that the Upstalsboom was a bronze or Iron Age burial mound. The reason for this was incorrect information in a museum catalog. There, the Upstalsboom was given as the location for two urns that the East Frisian Landscape had donated to the Society for Fine Arts and Patriotic Antiquities in Emden in 1873. However, these two urns were not the ones Meyer found at the Upstalsboom. Meyer himself mentions only one vessel. A drawing by Meyer has been preserved of this. The find is therefore "an approximately 20 cm high, early medieval import vessel decorated with scroll wheels, which can be dated to the second half of the 8th or 9th century".

Further finds, a sword and a second urn, came to light when the excavation pit for the stone pyramid was excavated in 1833. The finds can be seen today in the Historical Museum in Aurich . After 1833 the area remained untouched for a long time. In 1990 the working group Prehistory of the East Frisian Landscape began with a systematic investigation of the Upstalsboom hill. The aim was to find evidence for the hypothesis put forward by the head of the Archaeological Research Center, Wolfgang Schwarz, that the Upstalsboom was a burial mound built in the early Middle Ages. The working group was able to confirm this by finding remains of corpses, early medieval clay pot fragments and an iron buckle. Accordingly, the mound contained two, possibly three body graves, namely those of a man and two women. These were buried with rich grave goods, so that they were probably for socially outstanding people. Findings that could be related to the Diet of the Frisians, however, are not yet available.

literature

- Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legend, Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2003

- Ernst Andreas Friedrich : The Upstalsboom in Aurich , pp. 146-148, in: If stones could talk , Volume I, Landbuch-Verlag, Hannover 1989, ISBN 3-7842-03973 .

- Pieter Gerbenzon: Apparaat voor de study van Oudfries right . Noted by Barendina S. Hempenius-van Dijk. 2 volumes. 1981 (no location).

- Gerhard Köbler : Lexicon of European legal history . Munich: CH Beck 1997, p. 593.

- Karl von Richthofen : Frisian legal sources . Reprint d. Edition Berlin 1840, ed. by Karl Otto Johannes Theresius von Richthofen. Aalen: Scientia Verlag 1960.

- Herbert Röhrig : East Frisia . The country around the Upstalsboom , Bremen: Friesen-Verlag, 1927

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legend , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 424

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: The site of the Upstalsboom. The archaeological perception of the Upstalsboom . P. 406. In: Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , pp. 404-421.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: The site of the Upstalsboom. The archaeological perception of the Upstalsboom . P. 406. In: Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 . P. 404

- ↑ Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich In: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legend , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 423

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: The Upstalsboom. Assembly place of the Frisians near Rahe. In: Rolf Bärenfänger : Guide to archaeological monuments in Germany. Vol. 35 Ostfriesland, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1415-8 . P. 168.

- ↑ Quoted from: Kulturportal Nordwest: The Upstalsboom - Visible Sign of Frisian Freedom , viewed on March 16, 2013.

- ^ Hajo van Lengen (ed.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legends , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 425

- ^ Karl Kroeschell: right and wrong of the sassen. Legal history of Lower Saxony . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Göttingen 2005. ISBN 3525362838 . P. 172.

- ↑ Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich In: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legends , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 431

- ↑ Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich In: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): Die Frisische Freiheit des Mittelalters - Leben und Legende , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 432

- ↑ Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich In: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legends , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 431

- ↑ a b Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich In: Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.): Die Frisische Freiheit des Mittelalters - Leben und Legende , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 432

- ↑ a b Willem Kuppers: Upstalsbom - the "Altar of Freedom". From the Landtag area of the Frisians to the Thingstätte in the Third Reich . In: Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legends , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 433

- ↑ Bernhard Parisius : Approaching a Myth. On the history of the impact of Frisian freedom and the Upstals boom in the first half of the 20th century . In: Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian Freedom of the Middle Ages - Life and Legend , Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , p. 482.

- ^ Ostfriesische Nachrichten of February 25, 2013: Upstalsboom is to become a natural monument , viewed on March 15, 2013.

- ↑ Lower Saxony Heimatbund: White Portfolio 2015 . P. 7: Are “National Natural Monuments” designated in Lower Saxony? 202/15 ( Memento of the original dated February 7, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: The site of the Upstalsboom. The archaeological perception of the Upstalsboom . P. 406. In: Hajo van Lengen (Ed.): The Frisian freedom of the Middle Ages - life and legend . Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4 , pp. 404-421.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schwarz: Rahe FStNr. 2510/5: 1, City of Aurich, District Aurich Upstalsboom , viewed on March 16, 2013.

- ^ Rolf Bärenfänger: Finds from the Upstalsboom . In: Jan F. Kegler, Ostfriesische Landschaft (Ed.): Land der Entdeckungen - land van ontdekkingen 2013. The archeology of the Frisian coastal area , Soltau-Kurier Norden, Norden 2013, ISBN 3-940601-16-0 .

Coordinates: 53 ° 27 '14.8 " N , 7 ° 25' 52" E