Verulamium

Verulamium was the third largest city in Roman Britain . It was southwest of today's city of St Albans in Hertfordshire . Large parts of the city have so far been examined by archaeologists . Other parts are unexplored under agricultural land, under a park or have been built over. The center of the site, which is now a Scheduled Monument (protected archaeological site), is the Verulamium Museum and the Verulamium Hypocaust .

The Celtic city

The settlement was probably founded in pre-Roman times by Tasciovanus , the leader of the Catuvellaunen , who also had coins made here, as the capital of the tribe as Verlamion and is thus one of the first settlements in Britain, which is named. The exact location of the Celtic city is not entirely certain. Numerous Celtic trenches and numerous burials were found in and around the Roman city, but the area of the later Roman city does not seem to have been identical to the center of the Celtic city, as only sparse remains of pre-Roman buildings were found there. The Celtic city was apparently much larger and comprised not only the later Roman city, but also large areas to the west of it, where remains of settlements, ceramics, but also extensive ditch systems were discovered. Numerous rift systems also came to light north of the city.

A Celtic graveyard was excavated west of the city at Harry Lane , dating from around 25 BC. Until 25 AD was occupied. There were mainly urns, but also body burials. Various trenches could be found that fence at least eight grave districts. In the case of the urn burials there were usually grave goods, while there were none in the case of the body burials. One grave stood out for its rich furnishings, and is one of the richest Celtic burials ever found in England. There are attempts to connect the burial with a historical figure. The exact chronological order of the tomb is uncertain, if it dates from AD 45 to 50, as suggested, it may have belonged to a Roman client king. Britain was conquered by the Romans in 43 AD.

The Roman city

The city is located in a river valley on the Ver , which comes from the north and flows into the Colne a few kilometers south of the city . The river is no longer navigable today, but it may have been navigable at least for smaller ships in ancient times.

The Roman settlement was also on Watling Street , which ran north from the coast via Londinium . The road was laid out as an important infrastructure measure at the beginning of Roman rule. Wheeler suspects that the residents of the Celtic city, which was rather loosely built, moved close to the street in a short time, as economic advantages were to be expected there. Shortly after the Roman conquest of Britain, a small military camp appears to have been built in the Celtic city, but the evidence is very uncertain. In the following years the settlement grew into an important city and was finally, according to Tacitus ( Annals 14, 33), plundered and then destroyed in AD 61 during the Boudicca uprising of the Celtic Iceni and Trinovantes . This destruction could also be proven archaeologically on the basis of a layer of ash. We also learn from Tacitus that the city had the status of a municipality at that time. Since Tacitus was wrong several times in his information about distant places, it must be expected that he was wrong here. There is no further reliable evidence of the city's status. Life seems to have returned to normal quite quickly after the destruction of the uprising. The houses were mostly rebuilt in wood. From October 21, 62 AD, a document from Londinium reports that goods were shipped from there to Verulamium.

In 155 it was destroyed by a conflagration and then rebuilt in stone. Especially the fire around 155 seems to have changed the character of the city. A large part of the development up to this point consisted of smaller wooden buildings, often placed close together. The fire has been archaeologically proven, especially in the city center. After the fire, the reconstruction seems to have progressed rather slowly. Many areas in the city remained undeveloped for a long time. The wooden buildings were mostly replaced by larger city villas. There were also noteworthy buildings outside of the later city walls. which also included a public bath.

In the early 3rd century, the city, laid out according to a checkerboard pattern , which at that time had a wall, a deep moat, a forum , a basilica , a theater , thermal baths and several temples, already covered around 50 hectares. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, large city villas were also built, some of which were equipped with peristyle , mosaics and hypocausts and, in contrast to the other previously built, mostly very small residential buildings made of stone and not of wood.

Between 450 and 500, the Roman occupation finally ended and the city fell into disrepair.

Population numbers can only be roughly estimated. Sheppard Frere suspects about 15,000 inhabitants in the first and 20,000 in the second century. Rosalind Niblett is much more cautious and suspects hardly more than 1,000 inhabitants at the time of the Boudicca uprising and no more than 5,000 to 10,000 later.

There were various villas in the surrounding area, such as B. the Villa Rustica at Gorhambury , in Gadebridge Park , at Northchurch and at Boxmoor , in which wealthy townspeople lived and who provided the town with food.

Surname

The name of the city appears to be of Celtic origin. However, the etymology of the name is uncertain. The letters appear on Celtic coins. VER, VIR, VERL, VIRL and VERLAMIO. Otherwise, the city is rarely mentioned by ancient authors. The earliest mention comes from Tacitus in connection with the Boudicca uprising. When Claudius Ptolemy in his Geographike hyphegesis it appears as Urolanium and is considered one of two places in the territory of Catuvellauni called. The geographer of Ravenna , who dates around 700 but uses older information, appears the city as a Virolanium.

Post-Roman times

In the Middle Ages , the Abbey of St Albans , dedicated to the beheaded Saint Alban , was built northeast of the ruins, probably on the Roman cemetery , for the construction of which the Roman ruins were used as a quarry, so that today only parts of the city wall , a hypocaust and the theater are visible are.

Within the walls of Verulam, as Sir Francis Bacon called his barony , the essayist and statesman built a cultured little house that was detailed in his diary by John Aubrey in the 17th century. There are no remains of the house today. Aubrey stated: "At Verulam is to be seen, in some few places, some remains of the wall of this Citie."

Discovery and excavation

The knowledge about the location of the city was never lost. The area has always been known as the site of Roman coins and ancient architecture. Most of the city walls were visible. The first systematic excavations were carried out in 1847 by R. Grove Lowe, who examined the theater after it was found by accident. However, there were only a few further investigations in the period that followed. Between 1898 and 1911, Charles Bickwell and William Page dug in various locations in the city, most of which were able to locate the forum. Their investigations were rather modest by today's standards. Extensive investigations were carried out by Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler from 1930 to 1933 . Large parts of the city area were bought by the city of St. Albans in order to set up a park there. This gave the opportunity for the first systematic and, above all, scientifically higher-quality excavations. Several insulae, especially in the south of the city, have been examined and many townhouses, a temple and parts of the city wall have been exposed. The results were published in a monograph. Further excavations took place from 1955 to 1962 by Sheppard Frere, who dug in many parts of the city, but especially in the center. These studies were published in three volumes. Since then, smaller excavations have taken place again and again, often to clarify certain questions.

buildings

Forum

The forum formed the center of the city laid out according to a checkerboard pattern and was the second largest in Roman Britain with 161 × 117 m . According to an inscription placed under the governor Gnaeus Iulius Agricola , it was completed in 79 AD, i.e. in Flavian times. Its exact appearance is unclear despite several excavations. What is certain is that the forum has been rebuilt several times, although it is difficult to separate the individual phases. The north-east side of the building consisted of a number of rooms, presumably open to the outside, which were presumably used as shops. Behind it was a second row of rooms, which probably opened to the inside of the forum. This was followed by the large basilica, next to which the actual forum, a 62 × 94 m square, was located, the entrances of which were on the southeast and northwest sides. There were three other buildings to the southwest, with the middle perhaps being the Curia .

A few fragments of a building inscription on Purbeck marble happened to be found in 1955 that allow a reconstruction of the text, even if questions remain unanswered in detail. Using the letters VESPA, the text can be dated with certainty under Emperor Vespasianus . The remnants of GRIC can be added to Agricola. Agricola was governor of Britain from 78 to 84. Vespasianus ruled until 79, which limits the creation of the inscription to the years 78 and 79.

Macellum

To the northwest of the forum stood the Macellum ( market hall ), which was built around 85 AD and consisted of two rows of shops. In the middle was a courtyard with a water pipe that brought water from the nearby river. From animal bones found nearby, the researchers concluded that, as is also known from other Macella , meat was probably also traded.

There are three construction phases. The first building dates to around 100 AD and is about 40 × 20 m in size. The building consisted of a courtyard with a sewer and rows of smaller rooms on both long sides. At the end of the 2nd century this building was demolished. The new Macellum was only half the size and now had a building with an apse in the courtyard. In the fourth century the building received a monumental facade and two pedestals were erected in the courtyard. The building was probably abandoned shortly afterwards and was replaced by other buildings that are poorly preserved.

theatre

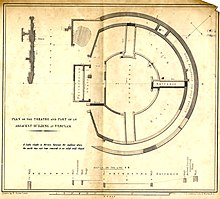

The city's theater has been the target of excavations several times. It was discovered and partly excavated by R. Grove Lowe in 1847, who also published his results extremely well for the time. Knowledge of the location of the theater was subsequently lost. However, it was found again in 1933 and re-excavated under the direction of Kathleen Kenyon .

The theater stood next to the Macellum and is one of the few buildings that can still be visited today. It was built around 140 AD, although it cannot be ruled out that there was already a theater at this point before. In the first phase, the building had an oval orchestra with a stage on the northeast side. The rows of seats were once probably made of wood and lined up on a pile of sand. The building, which consisted of a semicircular sitting room and a semicircular orchestra with a diameter of 24.3 m (Roman-Gallic type), was partly embedded in the ground. It is obviously a theater that was also used and designed as an amphitheater from the start. In a second construction phase, the stage was extended into the orchestra. The stage received a proscenium with a Corinthian order. This phase dates perhaps around AD 150. In a third phase of construction, the stage was extended on the sides and received a stone back wall. The building fell into disrepair in the 3rd century and was renovated at the end of the century. The auditorium was enlarged and a new outer wall was built.

It is very likely that the theater was connected to the neighboring temple district, so that religious events were probably also celebrated in the theater.

Thermal baths

So far, the remains of three thermal baths have been excavated on the Verulamium site.

During rescue excavations in Insula XIX, a sunk part of the building, a wall with pilasters, as well as remains of columns and high-quality wall paintings were found. According to the finds, it may have been a public building and was used until the end of the first century.

During excavations on Insula III, remains of buildings were also found, which probably belonged to a thermal bath, which was built at the end of the first century and destroyed in a great fire around 150. However, so far only three rooms of the building have been excavated, one of which had a hypocaust. Due to the structure of the building and the numerous toilet objects found, it is also fairly certain that it was a public bathroom. The building is in the middle of the city. Its location and the rich furnishings, including with Purbeck marble, indicate that this was the main bath in the city.

A third large bath was found in excavations northeast of the Roman city next to a large temple area, which is why it was possibly used primarily for ritual purposes. It has been studied almost completely. The building was at least 55 × 30 m in size, although spaces remain unexcavated in the north and west. The bath was built around 140 and was abandoned in the second quarter of the 3rd century. There is little evidence of remodeling

At least two houses (House IV, House 4, House V.1) had private bathrooms. A house in Insula XXXVII is only known from aerial photographs, but probably also had a bathing wing.

temple

The city had numerous temples. There were probably two classical-type temples in the forum. Other temples in the city are of the Gallo-Roman temple type , but only two of them have been excavated so far. The other temples are known from aerial photographs.

In Insula XVI, next to the theater and the forum, there was a large temple area (about 91 × 48 m) built at the end of the first century BC, which took up the entire insula, was surrounded by walls and turned north to the theater with which he was in communication, opened. In the middle of the district was the actual temple with a central cella, a gallery and two elongated extensions. Gates were located on the two short sides of the temple area. The east gate led directly to the theater.

In the south of the city, exactly opposite one of the city gates, a small, triangular temple area, also built at the end of the first century BC, was excavated, which also occupied a whole, albeit very small, insula.

Residential buildings

First century

The oldest buildings were concentrated in the center of the city in the area where the forum later stood. In the first and early second centuries, it was mostly relatively modest wooden buildings. Stone buildings were only erected more frequently in the second century.

In Insula XIV, a number of wooden structures could be excavated that date to the middle of the 1st century. The houses were burned down during the Boudicca uprising. They were probably shops with workshops. There were colonnades facing the street. The individual units consisted of the actual shop and a room behind it. Maybe there was a second floor that had living quarters. Receipts for metalworking were found in a shop.

Second and third centuries

In the first half of the second century, too, a large part of the residential buildings were made of wood. A good example is Insula XIV, where there were a number of shops and workshops with apartments behind them. There was a portico facing the street. In one house there were two aediculae made of stone, which are obviously house altars. Some rooms were decorated with wall paintings.

In the east of the city in particular, several large second-century townhouses have been excavated. They are mostly made of flint, which is abundant locally. Some of them are richly decorated with mosaics, wall paintings and hypocausts. House III.2 (the Roman numerals denote the insula, the Arabic numerals the house in the insula) was a large house, about 45 × 45 m in plan. It had a courtyard around which various rooms were arranged. Two construction phases could be distinguished. Especially in the first phase, the house had numerous rooms with hypocausts and mosaics. The first phase dates to the middle of the second century, the second to the end of the third century. House IV.8 was built in the middle of the second century. The building was once about 40 m long with two wings in the north and south. Above all, the south wing was found to be relatively well preserved, while the northern part of the building was destroyed down to the foundation walls and the floor plan could only be traced using foundation pits. In the south wing there was a large room with a well-preserved geometric mosaic. A smaller adjoining room contained a mosaic depicting a bust of a god. Most of the rooms could be heated. House II.1 once probably had a comparable floor plan, but it was much worse preserved. Noteworthy is a room with an apse, in which a semicircular mosaic depicting a shell was found.

House XXVIII.3 was built around 150. It was a wooden building, the wall and decoration of which can be reconstructed relatively well. Insula XXVIII was in the center of the city and separated the theater from the forum. The house consisted of two wings, both of which faced the street. At the back there was a courtyard. The house had a total of 10 rooms. The largest of them (room 3) was adorned with a mosaic showing a cantharus and dolphins as the central motif. The wall paintings were also well preserved and show red fields separated by stripes with floral motifs. Elaborate paintings come from a corridor, showing fields with imitation marble and columns in between. The house burned down at 155, so it only stood for about five years.

House XXI.2 was partly badly damaged by a medieval street, but the parts that have been preserved give a good impression of the furnishings of a wealthy citizen's house. The house was close to the forum and thus had a privileged location within the city. The flint house was built around 180 AD. It had three wings that were grouped around a courtyard. The north and east wings ran parallel to the ancient streets of the city. The northern wing in particular was largely destroyed in the Middle Ages. In contrast, the southwest wing was well preserved. There was a central room (7.47 × 4.42 m), the floor of which was decorated with a mosaic with a lion in the center. Numerous remains of wall paintings were found. The main wall was painted over a red base area with green fields, which were framed by red fields. To the east (towards the courtyard) of this room was a corridor that was 2.36 m wide and once about 15 m long. It was also painted. Here one found red fields with individual birds as a central motif. The fields are separated by lighter stripes. Filigree flower threads can be found within these fields. The base color of the ceiling was purple. A network of filigree plants forms rows of squares in which there are mostly birds, but also animal heads. In the south the corridor bent to the west (so that it had an L-shape overall). Here the ceiling was designed similarly, but with a red background. The walls again had a field decoration, but it was designed quite simply. The floor in both corridors was partly covered with red tesserae . Another room was north of the large central room. Apparently it had only white walls and a simple cement floor. The north wing of the house was apparently destroyed in the Middle Ages and is also under a modern street. The northeast wing had also suffered badly from stone robbery. There were a number of rooms facing the street and there was a corridor facing the courtyard. The house was inhabited for the entire third century, but the southwest wing was abandoned and leveled over time. The excavator points out that the well-preserved paintings and mosaics in the southwest wing indicate that the house was inhabited throughout the 3rd century and that the residents took care of the decoration.

- Wall paintings and mosaics from second century houses

Fourth and fifth centuries

In particular, the town villas on the outskirts seem to have been largely abandoned and have not been re-inhabited. On the other hand, there is clear evidence that the city center was still inhabited and that new, expensive residential buildings were also built.

House XXVII.2 was in the center of town, directly north of the forum, only separated from it by a street. The dating of the house caused some controversy. The insula itself had been built with wooden houses since the Flavian era. but they were poorly preserved. The buildings were destroyed in the town fire around 155 AD, after which the site remained undeveloped for a short time. House XXVII, 2 consisted of three wings around a courtyard that opened onto the street. Based on coins, the excavator seems to be certain that the building was erected around 380. Various rooms in the house had hypocausts and were furnished with mosaics over time, which accordingly date after 380. The building apparently operated until the middle of the 5th century, but was then demolished. A large hall was built in its place, the function of which is uncertain, but perhaps represented a memory. The hall was again demolished in the 5th century and a sewer was dug through the site. The archaeological evidence is particularly important and shows a wealthy urban upper class at the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century. It also testifies that even in the 5th century there was still considerable construction going on in the city. This contradicts the assumption that urban life in Britain died out with the departure of the Romans. However, more recent considerations date the house to the end of the second century. Above all, a built-in coin by Constans and Valens served as evidence of this late dating. However, more recent considerations make it more likely that the coins were used in the restoration of the building, since the mosaics in particular are stylistically much earlier, probably at the end of the second century.

city wall

Already in the first century the city was surrounded by a moat, the exact date of which is however controversial. It enclosed an area of about 40 hectares and was no longer in use in the third century because parts of it were built over. Another grave from the 2nd century that included the city. Its exact course is uncertain, as is its relationship to the first century ditch.

Extensive remains of the city wall are still standing today. It is made of flint and bricks, was once about 3.6 km long and enclosed an area of about 81 hectares. The wall was about eight feet thick and was probably four feet high. There were a few towers and at least four gates. The towers consist of a massive semicircle on the outside of the wall and an approximately 5 × 5 m room on the inside.

Several gates have been excavated. The so-called London Gate (the name is modern) in the south, on the road to London, is best preserved. It had two flanking towers and four passageways. The entire gate area is more than 10 m wide. In the middle there were two approximately 3 m wide gates, apparently for traffic on wheels, while there were also two narrower entrances for pedestrians. The northwestern Chester Gate was constructed in a similar way, but has been poorly preserved. The southwest gate was built according to the same scheme, but the corner towers were rectangular. The gate area was also narrower at around 10 m. There were also two entrances for pedestrians, but possibly only one central passage for vehicles. The dating of the city wall is not entirely certain, but there are indications that it was built in the third century.

Churches

Christianity had been the state religion in the Roman Empire since the fourth century AD. Objects with Christian symbols have not yet been found in Verulanum. The Anglo-Saxon Benedictine monk, theologian and historian Beda Venerabilis provides written evidence of the existence of a church in the city . It is unclear where the church was located. In the literature, however, three buildings are discussed as potential church structures, but none of the buildings has been proven to be used as a church.

One of the buildings is the temple district in Insula XVI, as its north-western entrance was probably closed during renovations, possibly to a church. A 15.8 m long and 12.5 m wide building in Insula IX, possibly a basilica, was also considered as a church due to the floor plan. There is no proof of the interpretation here either. A building with an apse, at least 6 m long and 3 m wide, found outside the former city in the middle of a burial ground in 1966 is also being considered as a church due to the shape of the building and its location in a burial ground, although no evidence of a church use was found here either were.

Triumphal arches

Remains of two triumphal arches have been excavated. One of them was in the south of the city. It was once about 15 m long and 5 m wide with two arches probably made of flint at the core. Only sparse remains of the foundations were found, but marble cladding came to light nearby, which may have adorned the arch. To the east of the theater, the remains of another triumphal arch have been excavated. Only one pillar was recorded during the excavations. The arch was built from bricks and possibly dates to around 300 AD.

graveyards

The cemeteries were mainly along the arteries of the city, outside the city walls. The cemeteries in the south were particularly popular in the first and second centuries. In the third century the arterial roads in the north and east were also occupied. In the fourth and fifth centuries, a hill east of the city was the main cemetery. In the first and second centuries, urn burials were the norm. From the second century onwards, body burials also occur, which become the rule from the third century onwards. Various burials were found in lead coffins. Sarcophagi are also attested. The foundations of some elaborate mausoleums have been preserved.

Business

Compared to other Roman cities, the evidence of industry and handicrafts is not very numerous. The city apparently owed its prosperity primarily to agriculture and was an important marketplace.

However, there is good evidence of ceramic production in and around the city. In the first century there were potteries operating about 4 km south of the city at Briket Wood (Lugdunum). In the second century, potteries operated outside the city near the South Gate (London Gate). Five pottery kilns have been excavated here. Inside the city, too, potteries worked in Insula V and XIII. Ceramic production in and around the city had its heyday in the first half of the 2nd century and supplied Londinium and the military camps on Hadrian's Wall . From the middle of the 2nd century onwards, however, production lost its importance and other places took over these functions.

There is ample evidence of metalworking. Even in pre-Roman times, the area seems to have been a center of iron processing. Evidence has repeatedly been found during excavations. Bronze slag also came to light during excavations. However, it is uncertain whether repairs were only made to metal objects or whether new objects were also produced on a larger scale. '

Meat seems to have played a special role in the city's economy, as evidenced by the meat market. However, animal bones found during excavations in the city have so far only been poorly investigated, while investigations have been carried out on the bones in some of the villas in the surrounding area. Beef bones dominate here. In the 2nd century, sheep bones are also represented in large numbers, but their proportion decreases over time. In some villas, sheep bones are still present in large numbers in the 4th century, whereby ss are often the bones of old animals. So the sheep were kept for the wool. There is evidence of leather processing related to cattle breeding. Mostly it concerns unprocessed leather remnants, which also testify to no major production.

Verulamium Museum

In the middle of the site is the Verulamium Museum operated by St Albans City Council and founded by Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler in the 1930s . It explains the history of the place in both the Iron Age and Roman times. It also shows the important excavation finds, including one of the best collections of floor mosaics in England, including the shell mosaic , stucco marble , the Verulamium Venus , a bronze figurine , and numerous other artifacts. Other finds also exhibited in the museum, such as a sarcophagus with a male skeleton, were discovered by chance during construction work.

- Exhibits of the Verulamium Museum

literature

- Neil Faulkner: Verulamium. Interpreting decline. In: Archaeological Journal 153.1 (1996), pp. 79-103.

- Sheppard Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume I, Oxford 1972

- Sheppard Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, Oxford 1983, ISBN 0-500-99034-4

- Sheppard Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume III, Oxford 1983, ISBN 0-947816-01-1

- David S. Neal, Stephen R. Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III: South-East Britain, Part 2 . London 2009, ISBN 978-0-85431-289-4 , pp. 307-351 .

- Rosalind Niblett, William Manning and Christopher Saunders: Verulamium. Excavations within the Roman town 1986-88. In: Britannia 37 (2006), pp. 53-188.

- Rosalind Niblett, Isabel Thompson: Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , Oxford 2005, ISBN 1-84217-149-6

- Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 .

- John Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain . Routledge, London / New York 1997, pp. 214-241 .

- REM Wheeler, TV Wheeler: Verulamium, A Belgic and two Roman Cities , Oxford 1936

Web links

- Verulamium Museum at stalbansmuseums.org.uk, accessed December 6, 2018

Individual evidence

- ^ Boundary of settlement walls , Pleiades

- ↑ 1003515 - The National Heritage List for England. Retrieved June 30, 2014 . and related schedules.

- ↑ Wacher: Towns of Roman Britain , 214-217

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 43-46 .

- ^ Wacher: Towns of Roman Britain , 217

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 29 .

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 24

- ^ Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City , pp. 56-57

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 26-28

- ↑ Roger SO Tomlin: Roman London's first voices: writing tablets from the Bloomberg excavations, 2010-2014 (= Mola Monographs. Volume 72). MOLA, London 2016, ISBN 978-1-907586-40-8 , 156-159

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume III, 26-28

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 12

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 108 .

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , p. 6

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium, A Belgic and two Roman Cities , Oxford 1936

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume I-III, Oxford 1972–1984

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 73-77 .

- ↑ RPWright: A note on the Inscription , in: The Antiquaries Journal , XXXVI (1956), 8-10; Donald Atkinson: The Verulamium Forum Inscription , in: The Antiquaries Journal , XXXVII (1957), 216-18; Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 69-72

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 77 .

- ^ Niblett: Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , pp. 102-105

- ^ R. Grove Lowe: A Description of the Roman Theater at Verulam , in: St. Albans Architectural Society . 1948 online

- ↑ Kathleen K. Kenyon: The Roman Theater of Verulamium , in: St. Albans and Hertfordshire, Architectural and Archaeological Society's Transactions, 1934 online

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 123-124

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 127

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 128

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 127-128

- ^ Niblett: Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , p. 85

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 77 .

- ^ Niblett, Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , p. 84

- ^ Niblett, Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , p. 86

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 110 .

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 78 .

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume I, 13-23

- ↑ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume I, 54-73

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 94-96

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 102-197

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 86-89

- ^ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 236–241

- ↑ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 157-178

- ↑ Frere: Verulamium Excavations , Volume II, 203-228

- ^ Neal, Cosh: Roman Mosaics of Britain, Volume III , 344-345

- ^ Niblett, Alban's Buried Towns, An Assesment of St 'Albans Archeology up to AD 1600 , pp. 66-71

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 59-63

- ↑ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , 63-73

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 123-124 .

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 136-37 .

- ↑ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , pp. 76-77

- ^ Wheeler, Wheeler: Verulamium , p. 129, pl. XXXVI

- ↑ Rosalind Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City of St Albans . Stroud 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1915-3 , pp. 120-22 .

- ^ Niblett: Verulamium, The Roman City , 102-104

- ↑ Verulamium Museum at stalbansmuseums.org.uk (English), accessed on December 6, 2018.

Coordinates: 51 ° 45 ′ 0 ″ N , 0 ° 21 ′ 14 ″ W.