Victory Boogie Woogie

|

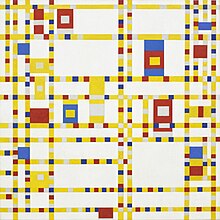

| Victory Boogie Woogie |

|---|

| Piet Mondrian , 1942–1944 (unfinished) |

| Oil and paper on canvas |

| 127 × 127 cm |

| Gemeentemuseum The Hague, Netherlands |

Victory Boogie Woogie is the last unfinished composition by the Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian , created between June 1942 and January 1944 in New York . The picture is considered to be the culmination of the Mondrian collection of around 300 works in the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and one of the most important works by a Dutch painter in the 20th century.

Thanks to a donation from the Nederlandsche Bank (Dutch Central Bank), the work was acquired by a foundation in 1997 for 82 million guilders (37.2 million euros ) and made available to the museum on permanent loan. The process led to controversy among the Dutch public and to questions in parliament, as a result of which the work received even greater media attention.

Work description

Victory Boogie Woogie has the dimensions 127 × 127 cm and is painted with oil paint on canvas . Mondrian also used painted paper and cellophane strips and black chalk. The rhombus shape is characteristic ; the entire canvas including the frame is rotated 45 degrees so that the vertical and horizontal axes are 179 cm. The work is mainly painted in the three primary colors red , blue and yellow as well as the non-colors white, gray and black. The areas divided on it, tiny areas and small squares, are arranged linearly, horizontally and vertically, and seem to dance in a wild rhythm on the screen like on a carpet that shimmers like music. White alternates with different shades of gray, blue with dark blue squares that appear to be almost black accents, and yellow that is replaced by broken yellow in prominent places. Even the red is varied, albeit less noticeably. The mixed up dancing colors and the dynamics of the broken network of lines correspond, according to reflections on the work, to the dynamic musical tempo of Boogie Woogie and the roaring rhythm in the streets between the blocks of the metropolis of New York . Because of these correspondences, video animations were published that highlight this interpretation of the work to a special degree.

Witness to the creation

In January 1941, the painter Charmion von Wiegand visited Piet Mondrian in his studio and saw a composition with colored lines that was taped “like a mummy”. It was the beginning of his new way of working, in which he used colored (or even painted) tape in the creation phase of his compositions. After interviewing the artist on April 12, 1941, they became friends and she visited him regularly during the last three years of his life. Von Wiegand noted her memories of Mondrian in her diary and witnessed the process of creating the painting and Mondrian's two-year struggle over the image concept.

| Sketch based on the original Victory Boogie Woogie by Piet Mondrian in the first phase of creation |

|---|

| Charmion von Wiegand , 1942 |

| Chalk on paper |

| approx. 21 x approx. 21 cm |

|

Link to the picture |

In early 1942 she visited Mondrian again, and he met her in the corridor and waved a piece of paper. He explained that he had dreamed of a magnificent composition and showed the paper with the first sketch for Victory Boogie Woogie . According to von Wiegand, Mondrian was never finished with the work. He was constantly working on it and showing the interim results to his friends. She once asked him why he wasn't doing a series instead of continuously working on experiments. He replied that he was not interested in too many paintings, but preferred to do one painting really well. Mondrian actively included von Wiegand in his work on the picture. She made suggestions and he tried them, rearranging pieces of tape and breaking lines.

In January 1944, Mondrian had already been working on Victory Boogie Woogie for two years . During a visit to Wiegands at the time, Mondrian had a bad cold and looked bad. They looked together at the picture, which looked very good and appeared to be finished. According to Mondrian, the only thing missing now was a last brush stroke on the upper edge. A week later von Wiegand found him sick in bed. Harry Holtzman called for a doctor. Mondrian was rushed to hospital that same day. It was only at this point in time that Wiegand noticed that painting had changed again.

Victory Boogie Woogie and Mondrians last ten days

Mondrian had worked intensively on the picture for the last ten days of his life. In his necrology , Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator Johnson Sweeney spoke of Mondrian's struggle with Victory Boogie Woogie : “Three days before he was rushed to the hospital, he had started to drastically change his newest painting, actually it was almost ready to be exhibited after working on it for more than nine months. Charmion von Wiegand was also affected by the 'radical changes' to Victory Boogie Woogie . On January 17, 1944, all strips of tape had been removed, but now it was full of tape again, and it looked as if Mondrian had been working feverishly again on the work. It had gotten a more dynamic quality, and it seemed to have more small squares with painted tape in different colors applied. Mondrian reconsidered the almost completed work between January 17 and 23, 1944, tearing himself away from all straight lines and expanding the area. ”Early on the morning of February 1, 1944, Mondrian died of pneumonia, his last work he left unfinished.

Surname

The name Victory Boogie Woogie does not originate, or at least it is not documented in writing, from Piet Mondrian. It is known, however, that he saw the work as a continuation of the earlier Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-1943) and that he mentioned the term "Victory" (victory). Presumably Mondrian's estate administrator and heir Harry Holtzman is the formal namesake, although the picture was given its definitive name during the six-week memorial exhibition that Holzmann organized in his studio immediately after the artist's death.

It has been described several times that Mondrian liked to dance, even when he was seventy in New York, and that he loved jazz. At the beginning of his time in New York, his protégé Holtzman first introduced him to the new boogie-woogie music and passed on Mondrian's reaction: “Enormous! Enormously! Huge! ”Exclaimed Mondrian when Holtzman played him the first boogie-woogie records. Sean Sweeney, son of MoMA curator James Johnson Sweeney, who often accompanied his father on visits to Mondrian's studio, recalled Mondrian's preference for boogie woogie: "He liked to play Gene Krupa 's drum boogie for me and joked about it, that he collected jazz records, although they were round and not square like the beloved colored surfaces on his walls and paintings ”.

“Victory” in the title probably indicates the expected victory of the Allies in World War II as well as Mondrian's overcoming of the earlier strict compositions in favor of the new musical rhythm of the motif. Hans Locher, the director of the Gemeentemuseum, put it: “The Victory Boogie Woogie is the triumphant answer to the Second World War. The famous Guernica by Picasso is the par become image for violence and war victims in the twentieth century. Well, Victory Boogie Woogie by Mondrian is the ultimate image for the victory of joie de vivre and freedom ”.

Provenance

Valentine Dudensing

Mondrian had designated Harry Holtzman as his executor and sole heir in his will. The only exception was Victory Boogie Woogie , which was bequeathed to his New York gallery owner Valentine Dudensing , who had paid Mondrian $ 400 in advance for the painting. From the second year of his stay in New York until his death, Mondrian found himself in a financially secure position as Dudensing easily sold Mondrian's paintings for $ 200 and beyond.

Emily Hall Tremaine

Emily Hall Tremaine's biographer, journalist Kathleen L. Housley, describes how Tremaine became the owner. The gallery owner Dudensing announced that he wanted to show her the most exciting work she had ever seen. Despite the addition that it was not for sale, the type of announcement did not fail to have its effect. Tremaine, already an experienced collector of modern art with an already considerable collection at the time, had never been so touched by a painting as by her encounter with Victory Boogie Woogie , and she absolutely wanted the work in her collection. She made Dudensing an offer that he couldn't refuse because he had provoked it himself. If he could buy a château in France with the proceeds, he would want to part with Victory Boogie Woogie , he had said casually. During the turmoil of the final months of World War II in semi-liberated France, the request was made for a staggering 8,000 US dollars. Burton Tremaine, husband of Emily Tremaine, is said to have elicited the statement: "Not a lot of money for a château, but a lot of money for a Mondrian." From 1944 to 1988, Victory Boogie Woogie remained in the Tremaines' possession, and the book cover of her biography became illustrated with the picture.

Samuel Irving and Victoria Newhouse

The next change of ownership was brokered in 1988 by Larry Gagosian . The process was mentioned in a book about today's art market, which deals with the rise of the globally represented gallery owner who is now considered prominent. The price was $ 10 million. The new owner became the newspaper magnate and billionaire Samuel Irving Newhouse , one of the 100 richest Americans, who bought it as a gift for his wife Victoria, possibly because the title of the picture contained her name. Victoria's study and bedroom in Manhattan became the new location . The picture looked, so to speak, on the skyline of the Big Apple , which had been one of the sources of inspiration for Mondrian.

Acquisition efforts by the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

The Hague Museum had become the worldwide ancestral home of Piet Mondrian's works by the estate of Salomon B. Slijper at the latest since the 1970s and owned around 300 works. In collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag organized a major Mondrian retrospective in 1994. Victory Boogie Woogie , the crowning glory of Mondrian's oeuvre, was loaned to the Museum of Modern Art by Samuel Irving Newhouse for the exhibition, but Newhouse refused to transport it across the Atlantic to The Hague for the second venue of the joint retrospective. The official reason was the fear that the painting could be damaged during transport. However, he sensed a deal and offered the Gemeentemuseum the work, probably for 14 million US dollars , for sale. If the purchase is completed, the prominent exhibit could still be shown in The Hague. The Gemeentemuseum managed to raise about 12 million US dollars, but not the required 14 million US dollars. Since the purchase did not materialize, the 1994 retrospective was shown in The Hague without Victory Boogie Woogie . Relations with the New Yorkers had been severely disturbed since then, as the Gemeentemuseum had sent a large number of works to New York.

Purchase by the Dutch state

Jan-Maarten Boll , chairman of the Vereniging Rembrandt , an association that has existed since 1883 with 9,000 members and the aim of supporting museums with acquisitions, played a decisive role in bringing Victory Boogie Woogie to the Netherlands. He was in New York in 1994 at the large Mondrian exhibition, where he saw the work for the first time. When he found out that it was still privately owned, he did everything possible to lobby for the acquisition in the Netherlands. The new director of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, Hans Locher , became a partner . Victoria Newhouse was in the process of writing a book on museum architecture and had personal contact with Locher in this regard. The price has now to 40 million US dollars set. It was possible to enforce a purchase period by contract, by which the work had to be purchased by a certain point in time. The third and decisive person was the newly appointed director of the Dutch Central Bank Nout Wellink .

On the occasion of the already decided changeover from the guilder to the euro, the central bank set an example for the loss of the national symbol guilder, which had existed in the Netherlands for 850 years, by setting a different national symbol. The central bank's annual profit of 130 million guilders (approx. 59 million euros), which should have been added to the reserves and which would have benefited the European Central Bank, should now flow into a new art fund once. Since the bank did not want to manage this fund itself, a sister fund was set up at Vereniging Rembrandt, with Jan-Maarten Boll as chairman. Wellink agreed that the majority of the fund should be immediately spent again to purchase Victory Boogie Woogie . The state, the sole shareholder of the central bank, had to approve the entire process. The then finance minister Gerrit Zalm gave his consent, whereby the fund could be founded under the name Stichting Nationaal Fonds Kunstbezit . The foundation's first action was the purchase of Victory Boogie Woogie , which in this way came into state ownership. The management was transferred to the Instituut Collectie Nederland and the picture went on permanent loan to the Gemeentemuseum. The composition was presented to the Dutch public on August 10, 1998 in the Gemeentemuseum, with great sympathy from the press, the art world and in the presence of Queen Beatrix and Crown Prince Willem-Alexander .

Controversy after the purchase

The press protested vehemently against the purchase, especially against what was believed to be the exorbitantly high amount for an unfinished work of art, which was only a few blocks of color with scraps of painted adhesive tape still hanging on them. The question arose whether something more useful could not be done with the money. In the Dutch parliament , questions were asked about the secret procedure by the Dutch central bank and the responsible finance minister, Gerrit Zalm, who, according to some questioners, escaped the parliament's legal control. Others, on the other hand, agreed to the procedure and considered it to be a successful campaign because it had avoided further price gouging. The debate was shaped by State Secretary Rick van der Ploeg , who was defending the minister and who was used in the press with rather ironic words that many know the price of a lot, but the real value of nothing. They finally acquired The 20th Century Night Watch . Ultimately, the procedure remained without formal consequences and the protagonists kept their offices.

research

In September 2006 and a second time in March 2007 Victory Boogie Woogie was taken out of its frame for research purposes and examined with modern non-contact research methods such as infrared , UV light and X-rays . Under the direction of Maarten van Bommel from the Instituut Collectie Nederland and Hans Janssen, curator of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, a team of international specialists tried to research the history of its creation and to document it and the condition of the work. The process was documented in a film and commented on in a newspaper blog by the curator in de Volkskrant . Visitors to the museum could also watch the work behind a glass wall. Details invisible to the naked eye became known for the first time. Results were, for example, that the work was in good condition in terms of materials, that the large areas were created in one painting process, but the small squares had been changed many times, which was also scraped off, and that Mondrian had used glue, adhesive tape, paper and cellophane strips. The result was also a complete visualization of the history of its creation.

Movie

On the tenth anniversary of the acquisition by the Netherlands, a television documentary produced by VPRO was broadcast on the Nederland 2 program in 2008 . She described the processes at that time and dealt with, among other things, comments and reflections on the painting.

In 2009 a film called Boogie Woogie came out. The film is a satirical comedy on the postmodern art world. It is based on the book of the same name by Danny Moynihan . Book and film title is avowedly borrowed from the Mondrian picture and the plot is partially inspired by the conveyance of Larry Gagosian's picture to Newhouse.

On September 24, 2011, AVRO broadcast a feature in the series Lamoree en de Meesters that looks at painting from the artistic side.

Miscellaneous

In the late 1980s, the Dutch central bank prepared a new series of banknotes. Mondrian and his work Victory Boogie Woogie should be depicted on the nominally largest note of 1000 guilders (about 454 euros) . However, the drafts were not implemented, partly because of the European plans.

To mark the 50th anniversary of Mondrian's death in 1994, a 90-cent stamp was issued in the Netherlands with a picture of a detail of Victory Boogie Woogie . In addition, Piet Mondrian's initials PM characterize the stamp with another meaning of PM: Pro Memoria, Latin with the meaning to remember.

American President Barack Obama was among the many millions of visitors who have seen the painting over the years in March 2014 . He paid particular attention to the work in the exhibition Mondriaan & De Stijl in the Gemeentemuseum The Hague.

literature

- Maarten van Bommel, Hans Janssen and Ron Spronk: Victory Boogie Woogie uitgepakt . Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2012, ISBN 978-90-8964-371-1 .

- Hans Janssen, Joop Joosten, Yve-Alain Bois, Angelica Zander Rudenstine: Mondriaan (exhibition catalog), Haags Gemeentemuseum.

- Jay Bradley: Piet Mondrian. 1872-1944. The Greatest Dutch Painter of Our Time. In: Knickerbocker Weekly , February 14, 1944.

- Kathleen L. Housley: Emily Hall Tremaine. Collector on the cusp. Meriden / New York 2001.

- LLM van Kollenburg: Victory Boogie Woogie. Reconstructie van een omstreden aankoop. Masterscript of Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen, Universiteit van Tilburg.

- JL Locher: Piet Mondriaan, Victory Boogie Woogie. Zwolle / The Hague 2000.

- Joop M. Joosten, Robert P. Welsh: Piet Mondrian. Catalog raisonné . Two volumes (English). Prestel, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7913-1698-2 .

Web links

- Victory Boogie-Woogie website from the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. (English, Dutch)

- Website about Victory Boogie Woogie and its purchase by the Dutch government 1997–1998 (Dutch)

- Mondrian Trust . Right holder of the reproduction rights to Mondrian's work

- Radio interview with Victory Boogie Woogie researcher Maarten van Bommel (Dutch)

Individual evidence

- ^ Susanne Deicher: Mondrian. 1872-1944. Construction above the void . Taschen, Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-8228-0928-0 , p. 90.

- ↑ Video animation for Victory Boogie-Woogie, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag , accessed on May 21, 2019

- ↑ Video animation by Willem van den Hoed, published on the De Volkskrant online website and the associated website toward victory online (Dutch), accessed on April 2, 2012.

- ↑ Margaret Rowell: Interview with Charmion von Wiegand, in Piet Mondrian Centennial Exhibition , Guggenheim Foundation, 1971 online

- ↑ a b c d e f Movie and related website for the purchase of Victory Boogie Woogie in 1997-1998, accessed online on March 28, 2012.

- ^ Page of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag on Victory Boogie Woogie , accessed on March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Michel Seuphor: Piet Mondrian. Life and work. Publisher M. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1957, p. 129.

- ↑ John Sharidan: Mondrian and Victory Boogie-Woogie: a radical couple about town online

- ↑ Dietmar Elger: Abstract Art . Taschen, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-8228-5617-8 , p. 56.

- ^ Hans Janssen, Joop Joosten, Yve-Alain Bois en Angelica Zander Rudenstine, Mondriaan (exhibition catalog), Haags Gemeentemuseum, p. 294, The Hague, 1995.

- ↑ Michel Seuphor: Piet Mondrian. Life and work. Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1957, p. 187.

- ↑ Kathleen L. Housley: Emily Hall Tremaine. Emily Hall, Tremaine Foundation, New Heaven 2001, ISBN 0-9705011-0-2 .

- ↑ Book cover of the biography of Emily Hall Tremaine with an illustration of Victory Boogie Woogie. Retrieved online March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Don Thompson: The 12. Million Stuffed Shark; The curious economies of contemporary art. Palgrave mcmillan, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-62059-9 , p. 71

- ^ Forbes' Richest Americans Online List , accessed March 28, 2012.

- ^ Website of the Vereniging Rembrandt ( Memento of April 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (Dutch), accessed on March 27, 2012.

- ^ Victoria Newhouse: Art and the Power of Placement. The Monacelli Press, New York 2005, ISBN 1-58093-148-0 .

- ^ Website of the foundation "Stichting Nationaal Fonds Kunstbezit" (Dutch) accessed on March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Instituut Collectie Nederland (ICN) website of the institute (Dutch) accessed on March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Film on Research on Painting 2006-2007 (Dutch)

- ↑ Data on the film Boogie Woogie on IMDb

- ↑ Lamoree en de meesters, Victory Boogie Woogie film online (Dutch), accessed March 31, 2012.

- ↑ Description and illustration of the planned 1000 Euro note online (Dutch), accessed on March 31, 2012.

- ^ Image of the stamp, accessed online on March 31, 2012.

- ↑ De Telegraaf, March 25, 2014, accessed online on March 25, 2014.

- ^ Website Gemeentemuseum Den Haag online ( memento of March 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on March 25, 2014.