William Macmichael

William Macmichael (born November 30, 1783 in Bridgnorth , † January 10, 1839 in Maida Vale , London) was an English doctor and writer. His fame today is based on his travelogue from 1819 and his medical biographies.

biography

Macmichael was born in Bridgnorth, the son of a banker. After completing school at Bridgnorth Grammar School, he received a scholarship and went to Christ Church College in Oxford in 1800 (BA 1805, MA 1808). From 1808 to 1810 he studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh , which is very renowned for this subject , before moving to London's St Bartholomew's Hospital , a well-known teaching hospital . After long trips abroad, his training as a doctor did not end until 1816 when he was awarded the title Medicinae Doctor (MD) in Oxford .

In 1811 he was granted a new scholarship, which enabled him to travel for several years through Russia and the Eastern Mediterranean (see below). Upon his return he became a member of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians . In the years 1817-1818 he returned to the continent before he settled in London as a practicing doctor. In 1822 he got a job at Middlesex Hospital in London, and that same year his first medical treatise appeared.

The anonymously published font The Gold-Headed Cane (1827) - "The stick with the golden headpiece" - was to become his most famous and to this day most widely read font; it contains five biographies of famous physicians (see below). Macmichael remained true to this interest and published three years later, again anonymously, the small volume Lives of British Physicians (1830), which now comprised eighteen biographies of doctors.

In 1829 Macmichael was appointed as a personal physician ( extraordinary ) to King George IV , and the following year he was also appointed to the position of royal librarian ( the King's librarian ). After the death of George IV (1830) Macmichael continued these activities under Wilhelm IV . The President of the Royal College of Physicians and full-time physician ( physician in ordinary ) of the two aforementioned monarchs, Sir Henry Halford (1766-1844), had ensured that Macmichael received these appointments at the royal court; like Macmichael, Halford was a graduate of Christ Church, Oxford (1791). Macmichael reciprocated by dedicating his booklet The Gold-Headed Cane to Lady Elizabeth Barbara St John Halford and his Lives of British Physicians to her husband Sir Henry .

Macmichael gave up his activity at Middlesex Hospital in 1831 and then held various positions at the Royal College of Physicians. From 1833 to 1835 he was employed as inspector general for London's madhouses ( lunatic asylums ). After an attack of paralysis in 1837, he was no longer able to work. He retired to his home in Maida Vale (then "Maida Hill"), where he died in 1839 at the age of only 55. Macmichael was married to Mary Jane Freer since 1827; the couple had a daughter.

Travel (1811-1818)

Between 1811 and 1818 Macmichael toured the European continent and the Eastern Mediterranean. In the first years he visited Russia, Greece, the Danube principalities, today's Bulgaria (then "European Turkey"), Asia Minor and Palestine. Unfortunately, there are no reports from his hand about his travels in Greece and Asia Minor.

In Greece he was infected with malaria at Thermopylae in 1812 , which hit him particularly hard over the next two years due to frequent attacks of fever. In 1814 he visited Moscow , which he found - only two years after Napoleon's invasion of Russia - largely destroyed. He then worked for a short time as personal physician for Charles Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry , in Vienna ; the latter had been appointed ambassador to Vienna and envoy to the Congress of Vienna in 1814 . Macmichael was forced to return to England, however, when his father's bank went bankrupt and much of the family's fortunes were lost. "That his father's bank went bankrupt when Dr. Macmichael was just beginning his career embarrassed him," Macmichael later wrote in a short biography.

After his final return to England, he published a detailed report on his last journey under the title A Journey from Moscow to Constantinople in the Years 1817, 1818 , which also included illustrations based on his drawings. The text was published in German in the Jena Ethnographic Archive that same year .

The journey from Moscow to Constantinople, which lasted about seven weeks and which Macmichael reports in his book, took place between mid-December 1817 and the first week of February 1818. The route comprised the following stops: Moscow ( December 4-16 , 1817) - Tula - Hluchiw (December 20) - Nizhyn (December 22) - Kiev - ( December 23-27 ) - Bohuslaw (December 29) - Pishtana (December 31) - Dubăsari (January 2, 1818) - Chișinău (January 4-6) - Iași (January 8-12 ) - Focșani (January 14) - Bucharest (January 16-23 ) - Ruse (January 25) - Veliko Tarnovo (January 27) - Gabrovo / Schipka Pass (January 28) - Kazanlak (January 29) - Stara Sagora (January 30) - Swilengrad (January 31) - Edirne (February 1) - Lüleburgaz (February 3) - Çorlu (4 February) - Arrival in Constantinople (February 6th). Macmichael soon returned from Turkey on a ship via Marseille ; one of his traveling companions continued his journey to Syria.

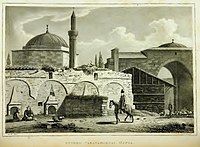

- Illustrations from Macmichael's Journey from Moscow to Constantinople (1819)

Promenade in Jassy ( Iași ), seen from the courtyard of the Vice Consul

The stick with the golden headjoint (1827)

In 1827 Macmichael published a small work of biographical sketches by five notable physicians at the Royal College of Physicians, namely John Radcliffe , Richard Mead , Anthony Askew , William Pitcairn and Matthew Baillie . These biographies are still considered to be important documents for the lives of these doctors, as they were for the history of medicine in the 18th century.

The peculiarity of Macmichael's book is that it describes the life and work of the doctors mentioned from the perspective of the cane with the gold-headed cane , which they led, owned and passed on one after the other; this stick is shown accordingly on the title page of the book. The idea of portraying doctors' biographies from the perspective of a stick was original, but not new: Theophilus Johnson had already published a book in 1783 with the title Phantoms: or, The Adventures of a Gold-Headed Cane (London: William Lane) , which was also written from the perspective of a walking stick.

The custom among medical professionals to use a (walking) stick with an ornate head joint (made of gold, silver or ivory) went back to the 18th century, but was already common in the 17th century and served partly as a professional symbol, partly as a status symbol. The special stick referred to in Macmichael's book was "in use" from 1689 to 1823, i.e. in the possession of the aforementioned doctors. When Matthew Baillie died in 1823, this tradition came to an end, and his widow, Mrs. Baillie, gave the stick to Sir Henry Halford and the London Royal College of Physicians in 1825 for further (museum) safekeeping. The family crests of Radcliffe, Mead, Askew, Pitcairn and Baillie are engraved on the gilded headjoint, and the object is still today, behind glass, as an exhibit in the library of the Royal College.

Macmichael's book about the gold-headed cane has an interesting follow-up story: After Macmichael had cured King Wilhelm IV of the gout, he gave him his cane with a gold-plated headpiece, because he no longer needed it.

Fonts

- 1819: Journey from Moscow to Constantinople in the Years 1817, 1818 . London ( Google ) (archive: color scan )

- German translation: "Journey from Moscow to Constantinople in the years 1817 and 1818. According to the English of Mr. William Macmichael". In: Ethnographisches Archiv , Volume 5 (Jena 1819), pp. 185-350.

- 1822: A New View of the Infection of Scarlet Fever, Illustrated by Remarks on other Contagious Disorders . London: Thomas and George Underwood ( Google )

- 1825: A Brief Sketch of the Progress of Opinion upon the Subject of Contagion; with some remarks on quarantine . London: John Murray ( Google )

- 1827 (anonymous): The Gold-Headed Cane

- First edition 1827, London: John Murray ( Google ); second edition 1828 ( Google )

- Third edition 1884, with notes and continuations by William Munk. London: Longmans & Co.

- New edition 1923: The Gold-Headed Cane . A new edition with an introduction and annotation by George C. Peachey. London: Henry Kimpton

- 1830 (anonymous): Lives of British Physicians . London: John Murray ( Google )

- Review and long excerpts: "The Lives of British Physicians". In: The Monthly Review , August 1830, pp. 600-612

- (Anonymous) new edition under the same title, London: Thomas Tegg 1846 ( Google )

- 1831: Is the Cholera Spasmodica of India a Contagious Disease? The Question Considered in a Letter Addressed to Sir Henry Halford, Bart, MD . London: John Murray ( Google )

- 1835: Some Remarks on Dropsy, with a Narrative of the Last Illness of the Duke of York, read at the Royal College of Physicians, May 25, 1835 (London, 1835)

literature

- William Munk: "William Macmichael, MD". In: The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London; Comprising Biographical Sketches of all the Eminent Physicians (...), 2nd edition, Volume III: 1801 to 1825 , London 1878, p. 182 f.

- Mark E. Silverman, "The tradition of the gold-headed cane". In: The Pharos , Winter 2007, pp. 42–46 ( pdf )

Web links

- " MACMICHAEL, William (1783-1839) " (Royal College of Physicians / Archives in London and the M25 area )

- William Macmichael: Autograph Letter Signed, as King's Librarian, to John Forbes Royle, informing him that the King is “graciously pleased to order a Copy of your work, 'On the Botany of the Himalayan Mountains”, for the Royal Library. 2 pp. 7 x 4 inches ( Historical Autographs )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Munk (1878), p. 182.

- ↑ See also: The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine . 3. Edition. University Press, Oxford 2001, pp. 141 .

- ↑ In Macmichael's time, the head of a cane was generally called "button" in Germany, see the reviews of his book in: Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung , No. 309 (December 1828), p. 795; Medicinisch-chirurgische Zeitung , supplementary volume 34 (January 13, 1831), p. 57.

- ↑ See also Christopher Flint: "Speaking Objects: The Circulation of Stories in Eighteenth-Century Prose Fiction" . In: Mark Blackwell (Ed.): The Secret Life of Things. Animals, Objects and It-Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England . Bucknell University Press, Lewisburg 2007, pp. 166 .

- ↑ For the topic in general: Dieter W. Banzhaf: doctor sticks. Symbol of a profession . 2nd Edition. Self-published, Heilbronn 2014.

- ↑ This and the following statements are taken from the article by Mark E. Silverman (2007).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Macmichael, William |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English doctor and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 30, 1783 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bridgnorth |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 10, 1839 |

| Place of death | Maida Vale , London |