Zumbi

Zumbi (pronunciation: [zũˈbi] ; * 1655 in Palmares (today União dos Palmares , Alagoas ); † November 20, 1695 at the Serra Dois Irmãos (today Viçosa , Alagoas)), also known as Zumbi von Palmares (Zumbi dos Palmares) , was the last leader of the autonomous community of Palmares of escaped and free-born slaves in what is now the Brazilian state of Alagoas.

Palmares

Palmares was a quilombo , d. H. Community of escaped African slaves , in northeastern Brazil ( formerly the Pernambuco captaincy , now the state of Alagoas ). From its founding around 1600, the residents successfully resisted the Portuguese colonial governments and Dutch colonizers. Escaped slaves often went back to their old plantations to help their former prisoners escape. So the settlement grew to about 30,000 people. Among them were Brazilian natives, Arabs and Europeans oppressed by the colonial government. Between 1654 and 1678, over twenty attacks by the slave-owning nations were repulsed.

Childhood and youth

Zumbi was born in freedom in Palmares in 1655. According to tradition, he was a nephew of Ganga Zumba (approx. 1630–1678), the leader of Palmares, and grandson of the Angolan princess Aqualtune , who founded Palmares. Captured by the Portuguese at the age of about six and given to the missionary Antonio Melo. Baptized as Francisco, he was initiated into the sacraments and learned Portuguese and Latin. At 15 he fled back to his birthplace. His combat strength and agility, as well as military skill, made him a respected strategist in his early twenties.

Leader of Palmares

In 1678 the Portuguese governor of the province of Pernambuco , Pedro Almeida , sought a conversation with the leader Ganga Zumba. His offer was to give the residents of Palmares freedom if the settlement surrendered to Portuguese violence. Ganga Zumba tended to accept, but Zumbi didn't trust the Portuguese. He also refused to accept freedom while others remained enslaved. In order to continue the resistance against the Portuguese oppression, he turned down Almeida's offer, thereby questioning Ganga Zumba's leadership and becoming the new leader of Palmares.

Fifteen years after Zumbi ascended the throne of Palmares and led his warriors to the gates of Recife , the Portuguese launched a cannon attack from three sides, which the fighters of Palmares were unable to cope with. After 67 years of unsuccessful war against Palmares, the Portuguese destroyed Cerca do Macaco, its central settlement, on February 6, 1694 . Zumbi was injured.

death

Although he managed to escape and continue the resistance for almost two years, his hiding place was ultimately betrayed by a prisoner comrade. Zumbi was beheaded on November 20, 1695 . His head was publicly exhibited in Recife to convince the African slaves of his death, whom Zumbi now believed to be immortal like a demigod. Yet the struggle continued for a hundred years after his death.

Today's meaning

In Brazil, the anniversary of Zumbi's death on November 20 is celebrated as Black Self- Awareness Day (Dia da Consciência Negra). Zumbi became the hero of the Afro-Brazilian human rights movement of the twentieth century, as well as a national hero.

memories

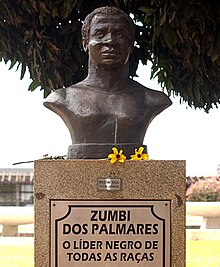

- Monuments

- The first monument to Zumbi, with a replica of a bronze head sculpture from Ife in today's Nigeria, was inaugurated after the end of the military dictatorship in 1986 on the central Avenida Presidente Vargas in Rio de Janeiro.

- Entry in the steel book of national heroes in the Panteão da Pátria e da Liberdade Tancredo Neves (1997)

- Life-size statue in Duque de Caxias near Rio de Janeiro (2002)

- Life-size statue in Salvador (Bahia) (2008)

- Bust in Petrópolis in the State of Rio de Janeiro (2009)

- Designations

- The Fundação Palmares ("Palmares Foundation"), founded in 1988, is an important cultural institution.

- The airport of Maceió in the state of Alagoas has been called "Zumbi dos Palmares" since 1999.

- The Faculdade Zumbi dos Palmares (Unipalmares) in São Paulo, founded in 2004, is a private university that is particularly dedicated to the education of Afro-Brazilians.

- In the federal capital Brasília , in Araras (São Paulo) and Curitiba (Paraná) places are named after Zumbi.

- music

- Name of the mangue beat band Chico Science & Nação Zumbi, founded in 1991 (after the death of frontman Chico Science in 1997 only Nação Zumbi )

- Zumbi is the subject of a song of the same name by MPB singer Jorge Ben Jor (1974)

- Mentioned in the song Ratamahatta by the metal band Sepultura (1996)

- Mentioned in several lyrics of the metal band Soulfly , especially in the song Zumbi (2002)

- Gilberto Gil released a CD called Z-300 Anos de Zumbi in 2002 .

- Movie

- Quilombo , 1984, feature film by Carlos Diegues about the history of Palmares with Antônio Pompêo in the leading role as Zumbi

- Capoeira

- Zumbi enjoys great admiration in Capoeira circles.

literature

- RN Anderson: The quilombo of Palmares: a new overview of a maroon state in seventeenth-century Brazil. In: Journal of Latin American Studies. Volume 28, 1996, pp. 545-566.

- Cheney, Glenn Alan. Quilombo dos Palmres: Brazil's Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, Hanover, CT, EUA: New London Librarium, 2014 300 p.

- PP A Funari: The archeology of Palmares and its contribution to the understanding of the history of African-American culture. In: Historical Archeology of Latin America. Volume 7, 1995, pp. 1-41.

- CE Orser Jr .: The archeology of the African diaspora. In: Annual Review of Anthropology. Volume 27, 1998, pp. 63-82.

- CE Orser Jr .: In search of Zumbi: preliminary archaeological research at the Serra da Barriga, State of Alagoas, Brazil. Midwestern Archaeological Research Center, Illinois State University.

Web links

- The Slave King ( Memento from February 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- 300 Years of Zumbi

- Taiguara performing the song composed in Zumbi's honor

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jane Landers: Leadership and Authority in Maroon Settlements in Spanish America and Brazil. In: José C. Curto, Renée Soulodre-LaFrance: Africa and the Americas. Interconnections During the Slave Trade. Africa World Press, Trenton pp. 173-184, here p. 179.

- ↑ Ana Lucia Araujo: Shadows of the Slave Past. Memory, Heritage, and Slavery. Routledge, New York 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e Ana Lucia Araujo: Public Memory of Slavery. Victims and Perpetretors in the South Atlantic. Cambria Press, Amherst (NY) 2010, p. 259.

- ↑ Habeeb Akande: Illuminating the Blackness. Blacks and African Muslims in Brazil. Rabaah, London 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Sergio González Varela: Capoeira, Mobility, and Tourism: Preserving an Afro-Brazilian Tradition in a Globalized World. Lexington Books, Lanham (MD) 2019, pp. 25-26, 98, 110-111.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zumbi |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zumbi of Palmares |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Leader of the autonomous kingdom of Palmares |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1655 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Palmares |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 20, 1695 |

| Place of death | Brazil |