John Lydon and Frank Rutter: Difference between pages

according to his autobio, JL is married to NF |

m →Futurism: wlink |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Person |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=October 2007}} |

|||

|name = Frank Rutter |

|||

{{Infobox musical artist |

|||

|image = Arts-and-letters-Spring-1920.jpg |

|||

|Name = John Lydon |

|||

|caption = Cover of ''Arts and Letters'', Spring 1920, co-edited by Frank Rutter |

|||

|Img = John Lydon.jpg |

|||

|birth_date = 17 February 1876 |

|||

|Img_capt = John Lydon in 1986 |

|||

|birth_place = [[Putney]], [[London]] |

|||

|Img_size = |

|||

|death_date = 18 April 1937 |

|||

|Background = solo_singer |

|||

|death_place = [[Golders Green]], [[London]] |

|||

|Birth_name = John Joseph Lydon |

|||

|other_names = Francis Vane Phipson Rutter |

|||

|Alias = Johnny Rotten |

|||

|known_for = Promoting [[Impressionism]] in Britain |

|||

|Born = {{Birth date and age|1956|1|31|df=y}}<br/>London, England |

|||

|occupation = [[Art critic]], [[curator]] |

|||

|Died = |

|||

|nationality = [[England|English]] |

|||

|Origin = |

|||

}} |

|||

|Instrument = [[Singer|Vocals]], [[Stroh violin]], [[Saxophone]], [[Guitar]], [[Bass guitar]], [[Violin]], [[Synthesizer]], [[Keyboards]], [[Percussion]] |

|||

|Genre = [[Punk rock]]<br/>[[Post-punk]]<br/>[[Alternative rock]] |

|||

|Occupation = [[Musician]], [[Singer-songwriter]] |

|||

|Years_active = 1975 – present |

|||

|Label = |

|||

|Associated_acts = [[Sex Pistols]], [[Public Image Ltd.]] |

|||

|URL = |

|||

|Current_members = |

|||

|Past_members = |

|||

'''Francis Vane Phipson Rutter''' (17 February 1876 – 18 April 1937)<ref name=whos>"Rutter, Frank V. P.", ''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007. Retrieved from [http://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whowaswho/U216578 ukwhoswho] 8 August 2008.</ref> was a British art [[art critic|critic]], [[curator]] and activist. |

|||

}}'''John Joseph Lydon''' (born 31 January 1956 in London, England), also known as '''Johnny Rotten''', is a British [[rock music]]ian, best known as lead vocalist for the [[punk rock]] group [[Sex Pistols]] and [[post punk]] group [[Public Image Ltd]]. |

|||

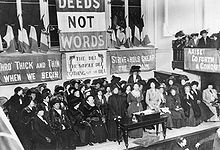

In 1903, he became art critic for ''[[The Sunday Times]]'', a position which he held for the rest of his life.<ref name=obit>''[[The Times]]'', 19 April 1937, p. 16, issue 47662, col B, "Obituary: Mr. Frank Rutter". Retrieved from [http://infotrac.galegroup.com infotrac.galegroup.com], 8 August 2008.</ref><ref name=glew/> He was an early champion in England of [[modern art]], founding the French Impressionist Fund in 1905 to buy work for the national collection,<ref name=taylor/><ref name=whos/> and in 1908 starting the [[Allied Artists' Association]] to show "progressive" art,<ref name=groveaaa/> as well as publishing its journal, ''Art News'', the "First Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom".<ref name =robins/> In 1910, he began to actively support women's [[suffragette|suffrage]], chairing meetings, and giving sanctuary to suffragettes released from prison under the [[Cat and Mouse Act]]—helping some to leave the country.<ref name=crawford/> |

|||

He has since become a television personality, appearing on television shows in both the UK and elsewhere. |

|||

From 1912 to 1917, he was the curator of [[Leeds City Art Gallery]].<ref name=obit/> In 1917, he edited the cultural journal, ''Arts and Letters'', with [[Herbert Read]].<ref name=aldington/> In his writing after [[World War I]], Rutter observed that [[advertising]] imagery was seen by far more people than work in art galleries;<ref>Saler, pp.101-102.</ref> he noted a new [[realism]] after the period of "abstract experiment";<ref name=x/> and he praised the work of [[Dod Proctor]] as a "complete presentation of twentieth century vision".<ref name=lang/> |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

He was born in London to [[Irish Catholic]] [[immigrant]]s, his father from [[Tuam]], [[County Galway]], and his mother from [[Shanagarry]],[[County Cork]].{{Fact|date=May 2008}} He grew up on a [[council estate]] in [[Finsbury Park]], [[North London]] with three younger brothers. At the age of seven, he contracted [[spinal meningitis]], putting him in and out of [[coma]]s for half a year and erasing most of his memory. The disease left him with a permanent curve in his spine. It also damaged his eyesight, resulting in his characteristic stare. He attended St. William of York School in [[Islington]], [[North London]], where his friends included David Crowe, Tony Purcell and John Gray. David Crowe went on to become involved with Public Image. John Gray became a school teacher and Tony Purcell went on to become a pioneer of the [[Internet]] industry in Scotland.<ref>p. 17, ''Rotten - No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs''. Picador, 1995. ISBN 0-312-11883-X.</ref> |

|||

== |

==Early life== |

||

===Sex Pistols=== |

|||

{{further|[[Sex Pistols]]}} |

|||

In 1975, Lydon was among a group of youths who regularly hung around [[Malcolm McLaren]] and [[Vivienne Westwood]]'s fetish clothing shop [[SEX (boutique)|SEX]]. McLaren had returned from a brief stint travelling with American [[proto-punk]] band the [[New York Dolls]], and he was working on promoting a new band formed by [[Steve Jones (musician)|Steve Jones]], [[Glen Matlock]] and [[Paul Cook]] called [[Sex Pistols]]. McLaren was impressed with Lydon's ragged look and unique sense of style, particularly his orange hair and modified [[Pink Floyd]] T-shirt (with the band members' eyes scratched out and the words ''I Hate'' scrawled in felt-tip pen above the band's logo). After tunelessly singing [[Alice Cooper]]'s "Eighteen" to the accompaniment of the shop's [[jukebox]], Lydon was chosen as the band's frontman. |

|||

Frank Rutter was born at 4 The Cedars, [[Putney]], [[London]], the youngest son of Emmeline Claridge Phipson and Henry Rutter (died 1896).<ref name=odnb>Owen, Felicity (article credit). [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/54009 "Rutter, Francis Vane Phipson",] ''[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]]'' (subscription required). Retrieved 11 August 2008.</ref> His grandfather, John, and his father were both prosperous solicitors with chambers in Cliffords Inn, Holborn, and both had acted for [[John Ruskin]], John assisting on Ruskin's marriage nullification with Euphemia (Effie) Gray; Henry severed the connection with Ruskin, after the latter rejected his counsel on a property transaction.<ref name=yeates85>Yeates, John. "N.W.1.: The Camden Town Artists— |

|||

The origin of the stage name ''Johnny Rotten'' has had varying explanations. One, given in a ''[[Daily Telegraph]]'' feature interview with Lydon in 2007, was that "he was given the name in the mid '70s, when his neglect of [[oral hygiene]] saw his teeth turning green".<ref name="Telegraph"/> Another story says the name was allegedly given to him by [[Steve Jones (musician)|Steve Jones]], after Jones saw his teeth and exclaimed "You're rotten, you are!" |

|||

A Social History'', pp. 85–96. Heale Gallery, Somerset, 2007. ISBN |

|||

9780955817601. Available online at [http://www.camdenschool.co.uk/NW1%20A%20Social%20History%20of%20the%20Camden%20School.pdf camdenschool.co.uk].</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Cambridge Queens' Gatehouse.JPG|thumb|Old Court Gatehouse of [[Queen's College, Cambridge]]]] |

|||

<!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: [[Image:John Destroy.jpg|thumb|right|Johnny Rotten c. 1977, photographed by Dennis Morris.]] --> |

|||

From 1889, Frank Rutter was educated at [[Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood|Merchant Taylors’ School]], at that time in [[Aldersgate]], where he specialised in Hebrew (under the influence of his father whose hobby was Biblical archaeology)<ref name=obit/> and where pupils were expected to gain Oxbridge scholarships or exhibitions in classics: Rutter, aged seventeen tried but failed to gain a scholarship in history at [[Exeter College]], Oxford, but was successful in the [[Queen's College, Cambridge]], examination for a scholarship in Hebrew,<ref name=yeates85/> going to university in 1896 and gaining the Semitic Language [[Tripos]] (degree) in 1899.<ref name=obit/> |

|||

In 1977, the band released "[[God Save the Queen (Sex Pistols song)|God Save the Queen]]" during the week of [[Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom|Queen Elizabeth II]]'s [[Silver Jubilee]]. The song was a hit, but caused so much controversy that Lydon was attacked in the streets by an angry mob. They stabbed him in his left hand, his leg, and nearly gouged out his eye with a beer bottle. Since then, he has not been able to properly make a fist with his left hand. |

|||

Whilst still at school, Rutter, along with a fellow sixth form student, Edgar D., explored London nightlife, visiting [[music hall]]s, eating out in Gatti's Restaurant and joining nightclubs, which were then an adjunct to the more formal London's gentleman's club, providing a dining room, ballroom, writing room, and female membership, which was not taken up by respectable women in society, although the male membership was mostly respectable; Rutter's father happily financed these activities.<ref name=yeates85/> |

|||

Lydon's interest in [[Dub (music)|dub music]] and his post-Sex Pistols work with [[Public Image Ltd.]] (also known as PiL) and artists such as [[Afrika Bambaataa]] and [[Leftfield]] showed him to be more musically sophisticated {{Fact|date=August 2008}} than his work with the Sex Pistols had suggested. McLaren was said to have been upset when Lydon revealed during a radio interview that his influences included progressive experimentalists like [[Can (band)|Can]], [[Captain Beefheart]] and [[Van der Graaf Generator]].<ref name="Reynolds">{{cite book | author = Simon Reynolds | title = Rip it Up and Start Again - Postpunk 1978-1984 | year = 2005 | publisher = faber and faber | id = ISBN 978-0-571-21570-6}}</ref> |

|||

When at Cambridge, Rutter gained popularity through his [[banjo]]-playing,<ref name=obit/> and, thanks to the good train service available, extended his social pursuits to Paris, first visiting in 1898, speaking French fluently and often staying for a month at a time in the city,<ref name=yeates85/> where he made friends in the [[Latin Quarter]].<ref name=obit/> |

|||

Tensions between Lydon and bassist [[Glen Matlock]] arose. The reasons for this are disputed and uncertain, however Lydon claimed in his autobiography that he believed Matlock to be too [[white-collar]] and [[middle-class]] and that Matlock was "always going on about nice things like [[the Beatles]]". Matlock stated in his own autobiography that most of the tension in the band, and between himself and Lydon, was orchestrated by McLaren. Matlock quit and as a replacement, Lydon recommended his school friend John Simon Ritchie. Although Ritchie was an incompetent musician, McLaren agreed that he had the look the band wanted: pale, emaciated, spike-haired, with ripped clothes and a perpetual sneer. Rotten dubbed him "[[Sid Vicious]]" as a joke, taking the name from his pet hamster, a finger-biting creature named Sid the Vicious. |

|||

After university, spent a few months as an itinerant tutor, then began as a freelance writer in London with a newly acquired typewriter.<ref name=obit/> One of his successful interviews was with [[Bernard Shaw]] on the subject of housing problems—the text of which was entirely provided by Shaw himself; ''[[The Times]]'' printed an interview with the American scout, Major Burnham, recently returned from [[South Africa]].<ref name=obit/> |

|||

Vicious' chaotic relationship with girlfriend [[Nancy Spungen]], and his worsening [[heroin addiction]], caused a great deal of friction among the band members, particularly with Lydon, whose sarcastic remarks often exacerbated the situation. Lydon closed the final Sid Vicious-era Sex Pistols concert in [[San Francisco]]'s [[Winterland]] in January 1978 with a rhetorical question to the audience: "Ever get the feeling you've been cheated?" Shortly thereafter, McLaren, Jones, and Cook went to [[Brazil]] to meet and record with former train robber [[Ronnie Biggs]]. Lydon declined to go, deriding the concept as a whole and feeling that they were attempting to make a hero out of a criminal who attacked a train driver and stole "[[working-class]] money". Lydon was abandoned in San Francisco virtually penniless. |

|||

He obtained posts as assistant editor of ''To-day'' and the ''Sunday Special'', both part of the same publishing group. In February 1901, he became sub-editor of the ''[[Daily Mail]]'', and began to write art criticism, mostly for ''[[The Financial Times]]'' and the ''[[The Sunday Times]]''.<ref name=obit/><ref name=whos/> In 1902, he went back to ''To-day'' as editor for two years, and for a short time brought it back into profit, until it succumbed to cheaper competition and was merged with ''London Opinion''.<ref name=obit/><ref name=whos/> In 1903, Leonard Rees appointed him [[art critic]] of ''The Sunday Times'', a post he held for the rest of his life, 34 years in all.<ref name=obit/><ref name=odnb/> Rutter honed his skills whilst doing the job, and also made the acquaintance of leading artists in Paris through frequenting the cafés.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

The Sex Pistols' disintegration was documented in [[Julian Temple]]'s [[Satire|satirical]] pseudo-[[biopic]], ''[[The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle]]'', in which Jones, Cook and Vicious each played a character. Matlock only appeared in previously-recorded live footage and as an animation and did not participate personally. Lydon refused to have anything to do with ''The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle'', feeling that McLaren had far too much control over the project. Although Lydon was highly critical of the film, many years later he agreed to let Temple direct the Sex Pistols documentary ''[[The Filth and the Fury]]''. That film included new interviews with band members hidden in shadow, as if they were in a [[witness protection program]]. It featured an uncharacteristically vulnerable Lydon choking up and becoming tearful as he discussed Vicious' decline and death. Lydon denounced previous journalistic works regarding the Sex Pistols in the introduction to his [[autobiography]], ''Rotten - No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs'', which he described as "as close to the truth as one can get".<ref>Lydon, John. ''Rotten - No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs''.</ref> |

|||

==The French Impressionist Fund== |

|||

Although Lydon spent years furiously denying that the Sex Pistols would ever perform together again, the band re-united (with Glen Matlock returning on bass) in the 1990s, and continues to perform occasionally. In 2004, Lydon publicly refused to allow the [[Rhino Entertainment|Rhino]] [[record label]] to include any Sex Pistols songs on its box set ''[[No Thanks!: The 70s Punk Rebellion]]''. In 2006, the [[Rock and Roll Hall of Fame]] inducted the Sex Pistols, but the band refused to attend the ceremony or acknowledge the induction, complaining that they had been asked for large sums of money to attend<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4750262.stm BBC NEWS | Entertainment | Sex Pistols snub US Hall of Fame<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> and stating that it went against everything the band stood for. |

|||

[[Image:Monet, Lavacourt-Sunshine-and-Snow.jpg|thumb|[[Claude Monet]]. ''Lavacourt Under Snow'', 1878–1881. Rutter's unsuccessful, too "advanced", choice for the [[National Gallery, London|National Gallery]].]] |

|||

In 1903 the creation of the [[National Art Collections Fund]] initiated many years of frustration for Rutter, who believed it would siphon off available money from his own aims.<ref name=lago>Lago, Mary. ''Christiana Herringham and the Edwardian Art Scene'', University of Missouri Press, 1996. ISBN 0826210244, ISBN 9780826210241</ref> He was a strong supporter of [[Impressionism|Impressionist]] and [[Expressionism|Expressionist]] [[Modernism]].<ref name=flint>Flint, Kate. ''Impressionists in England: The Critical Reception'', p. 33, Routledge.ISBN 0710094701, ISBN 9780710094704.</ref><ref name=taylor>Taylor, Brandon. ''Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public, 1747-2001'', p. 134, Manchester University Press, 1999. |

|||

[[Image:JohnLydon.jpg|Lydon with the Sex Pistols at [[Brixton Academy]] in 2007|thumb|200px]] |

|||

ISBN 0719054532, ISBN 9780719054532</ref> He considered "perfectly dreadful"<ref name=ruttertime114>Rutter, Frank. ''Art in My Time'', p.114–119, Rich & Cowan, London, 1933.</ref> the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only example of the modern French school was [[Edgar Degas]]' ''The Ballet from Robert the Devil'' (1876) in the [[Victoria and Albert Museum]].<ref name=taylor/> |

|||

In June 2007, Lydon, Jones and Cook re-recorded "Pretty Vacant" in a Los Angeles studio for the video game ''Skate'' and, in a radio interview in the same month, Lydon announced that the Sex Pistols may perform again over the [[Christmas]] period. They also re-recorded "Anarchy in the UK" for the video game ''[[Guitar Hero III: Legends of Rock]]''. In September 2007, Lydon announced that the Sex Pistols would play a concert for the 30th anniversary of ''Never Mind the Bollocks'' at the [[Brixton Academy]] on 8 November 2007. Due to popular demand, four additional concerts were added, as well as further shows in [[Manchester]] and [[Glasgow]]. |

|||

Raging with indignation, he wrote articles on this omission, gave lectures,<ref name=ruttertime114/> and, galvanised by the opening of the Impressionist exhibition staged by [[Durand-Ruel]] at the [[Grafton Galleries]] in London in 1905,<ref name=taylor/> he persuaded the editor and proprietors of ''The Sunday Times'' to allow space for a public subscription, the French Impressionist Fund.<ref name=ruttertime114/> Sargent and Wertheimer each sent ten guineas; Blanche Marchesi staged a fund-raising concert; Rutter, although "extremely nervous" gave his first lecture at the Grafton Galleries.<ref name=ruttertime114/> Sir Claude Phillips and [[D.S. MacColl]] joined him on the executive committee of the fund, and contributions slowly mounted up to £160, sufficient at that time to buy a top class Impressionist painting.<ref name=ruttertime114/> |

|||

The Sex Pistols will be appearing at the Isle Of Wight Festival 2008 as the headlining act on the Saturday night. They are also due to appear at the Peace and Love Festival in Sweden, Electric Picnic in Ireland, the Live at Loch Lomond Festival in Scotland, Heineken [[Open'er Festival]] in [[Gdynia]] (Poland), Paredes de Coura Festival in Portugal, Traffic Free Festival in [[Turin]] (Italy) and [[EXIT festival]] in [[Serbia]] the same summer. |

|||

Rutter's choice was [[Claude Monet|Monet]]'s ''Vétheuil: Sunshine and Snow'' (since retitled ''Lavacourt under Snow''), which MacColl was in favour of and Durand-Ruel had promised to sell for the amount collected, but Phillips pointed out that [[National Gallery (London)|National Gallery]] did not accept work by living artists; discreet enquiries revealed that the gallery trustees also found too "advanced" [[Édouard Manet|Manet]], [[Alfred Sisley|Sisley]] and [[Camille Pissarro|Pissarro]]: "They were certainly dead—but they had not been dead long enough for England", wrote Rutter, adding "I nearly wept with disappointment."<ref name=ruttertime114/> |

|||

===Public Image Limited (PiL)=== |

|||

{{Refimprove|section|date=September 2008}} |

|||

{{main|Public Image Ltd.}} |

|||

In 1978, he formed the [[post-punk]] outfit Public Image Limited (PiL) and denounced the Sex Pistols. PiL lasted for 14 years with John Lydon as the only consistent member. The group enjoyed some early critical acclaim for its 1979 album, ''[[Metal Box]]'' (a.k.a. ''Second Edition''), and influenced many bands of the later [[Industrial rock|industrial]] movement. The band was lauded for its innovation and rejection of traditional musical forms. Musicians citing their influence have ranged from the [[Red Hot Chili Peppers]] to [[Massive Attack]]. |

|||

[[Image:Boudin-The-Entrance.jpg|thumb|[[Eugène Boudin]]. ''The Entrance to Trouville Harbour'', 1888. The National Gallery accepted this painting.]] |

|||

The band's surreal performance on the dance/concert TV show ''[[American Bandstand]]'' has become the stuff of legend, with Lydon giving up on lip synching not long into the performance and dancing with audience members instead. The group did quite well in the UK charts, but were regularly outsold by Sex Pistols reissues. Despite his tenure with PiL, Lydon is still most well-known as ''Johnny Rotten''. |

|||

MacColl ascertained that the trustees would accept [[Eugène Boudin]], who Rutter protested was not an Impressionist but whom he accepted out of necessity, mollified by MacColl's argument that "he's the beginning of Impressionism and we can make a start with him."<ref name=ruttertime114/> To avoid any accusations of [[logrolling]] Durand-Ruel's exhibition, they agreed that Rutter would travel to Van der Veldt, a private collector in [[Havre]], to choose a Boudin painting. He brought back as personal luggage Boudin's 1888 painting, ''Entre les jetées, Trouville'' (''The Entrance to Trouville Harbour''),<ref>Variously titled also as ''Port of Trouville'' and ''Harbour at Trouville''.</ref><ref name=ruttertime114/> and wrote to MacColl on 11 October 1905 to inform him of the work he had selected, which Van der Veldt had accepted £120 for provided it would go to a national collection, and which was waiting at the Goupil Gallery for MacColl to see.<ref>[http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/manuSCRIPTs/search/detaild.cfm?DID=18297 "Manuscripts Catalogue - Document Details"], [[University of Glasgow]]. Retrieved 10 October 2008. The letter is dated 1906 in the archive, but it must have been written in 1905.</ref> |

|||

It was shown privately at the Goupil Gallery for the subscribers, and presented in January 1906 to the National Gallery through the [[The Art Fund|National Art Collections Fund]], which Rutter said was keen to act as a channel for the prestigious presentation, but had not given "the slightest help or encouragement when I needed it most."<ref name=ruttertime114/> It made Rutter "boil with rage" to contrast this with the Fund's spending of thousands of pounds on older paintings; he said, "the Fund's inertia and snobbish ineptitude are entirely characteristic of the art-officialdom in England."<ref name=ruttertime114/> |

|||

The first lineup of the band included bassist [[Jah Wobble]] and former [[The Clash|Clash]] guitarist [[Keith Levene]]. They released the albums ''Public Image'' (also known as ''First Edition''), ''Metal Box'' and ''Paris in the Spring''. Wobble then left and Lydon and Levene concocted the ''The Flowers of Romance''. Then came ''This Is What You Want...This Is What You Get'' featuring [[Martin Atkins]] on drums (he had also appeared on ''Metal Box'' and ''The Flowers of Romance'') as well as session artists. Lydon said of this album in 1992 that "''This is What You Want'' is just me giving orders and them receiving them. There was no feedback. If I had a crap idea, the crap idea would go onto vinyl almost immediately". However, despite the dip in quality as compared to their first three albums, it featured their biggest hit, the sarcastic "This Is Not A Love Song", which hit #5 in 1983. |

|||

==Allied Artists' Association== |

|||

Then in 1986 Public Image Limited released ''Album'' (also known as ''Compact Disc'' and ''Cassette''). Most of the tracks on this album were written by Lydon and [[Bill Laswell]]. The musicians were session musicians including bassist [[Jonas Hellborg]], guitarist [[Steve Vai]] and Cream drummer [[Ginger Baker]]. It continued the band's foray into accessible dance-pop as opposed to their earlier incarnation as a challenging art-rock ensemble. Like the previous album, this also featured a massive hit, the anti-[[apartheid]] anthem "Rise". |

|||

[[Image:Sickert.jpg|thumb|[[Walter Sickert]].]] |

|||

In 1987 a new lineup was formed consisting of Lydon, former [[Magazine (band)|Magazine]], [[Siouxsie & The Banshees]] and [[The Armoury Show]] guitarist [[John McGeoch]], [[Alan Dias]] on bass guitar in addition to drummer [[Bruce Smith]] and [[Lu Edmunds]]. This lineup released ''Happy?'' and all except Lu Edmunds released the album ''9'' in 1989. In 1992 Lydon, Dias and McGeoch were joined by Curt Bisquera on drums and Gregg Arreguin on rhythm guitar for the album ''That What Is Not''. This album also features the [[Tower Of Power]] on two songs and Jimmie Wood on [[harmonica]]. Lydon, McGeoch and Dias also wrote the song "Criminal" for the movie ''[[Point Break]]''. After this album, in 1993, Lydon put PiL on indefinite hiatus, in which state they remain today. |

|||

While in Paris in 1907,<ref name=odnb/> Rutter had the idea for gaining greater |

|||

exposure for progressive artists with the [[Allied Artists' Association]] (AAA), founded the following year and based on the model of the French [[Salon des Indépendants]] with the principle of non-juried shows of international artists, who could subscribe and choose which works they wished to enter (initially five pieces, later three). <ref name=groveaaa>"Allied Artists’ Association (A.A.A.)", [[Grove Dictionary of Art|Grove Art Online]], retrieved from [http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T001911?q=frank+rutter&source=oao_gao&source=oao_t118&source=oao_t234&source=oao_t4&search=quick&pos=5&_start=1#firsthit Oxford Art Online] (subscription site), 8 August 2008.</ref><ref name=robins>Sickert, Richard Walter; Robins, Anna Gruetzner. ''Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art'', p. xxxi, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0199261695, ISBN 9780199261697. Retrieved from [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9MO_OO_G4BsC&pg=PR2&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=0_1&sig=ACfU3U2idUfP8ODuBsE2tbu3wg2PrHjTOQ#PPR31,M1 Google Books].</ref> |

|||

Rutter was a supporter of the [[Fitzroy Street Group]], which had been founded in 1907, and succeeded in gaining the support of key members, [[Walter Sickert]], [[Spencer Gore]] and [[Harold Gilman]], for the AAA. Rutter was a natural organiser and, with the help of [[Lucien Pissarro]] attracted 80 members.<ref>Glew states 40 members.</ref><ref name=odnb/> Rutter was keen to mount a foreign section in the first show, and liaised over this with Jan de Holewinski (1871–1927), who was in London to arrange a Russian art and craft show.<ref name=groveaaa/> The first AAA show in July 2008 was in the [[Royal Albert Hall]] and had over 3,000 works on display.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

In December 2005, Lydon told ''[[Q (magazine)|Q]]'' that he is working on a second autobiography to cover the PiL years.<ref name="q">{{cite web |

|||

| url= http://www.johnlydon.com/q05.html |

|||

|publisher= ''[[Q (magazine)|Q]]'' |

|||

| title="The Q Interview: 'I want to take the Sex Pistols to Iraq!'"}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Vassily-Kandinsky.jpeg|thumb|[[Wassily Kandinsky]] c. 1913.]] |

|||

===Collaboration with Time Zone=== |

|||

In 1909, at the second show in the [[Royal Albert Hall]], over 1,000 works were shown, mainly by British artists, but also the first works (two paintings and twelve woodcuts) exhibited in London by [[Wassily Kandinsky]].<ref name=glew>Glew, Adrian. [http://www.tate.org.uk/tateetc/issue7/kandinsky.htm "Every work of art is the child of its time"], ''[[Tate Etc.]]'', issue 7, Summer 2006. Retrieved 8 August 2008.</ref> Rutter's friends in Leeds, Michael Sadler and his son, Michael Sadleir (who had modified the spelling of his surname) developed a relationship with Kandinsky, who assigned English translation rights for ''[[Concerning the Spiritual in Art]]'' to Sadleir.<ref name=glew/> |

|||

In 1984, Lydon worked with [[Time Zone (band)|Time Zone]] on their best-known single, "World Destruction". A collaboration between Lydon, Afrika Bambaataa and producer/bassist Bill Laswell, the single was an early example of "[[rapcore]]" predating [[Run-DMC]] and [[Aerosmith]]'s "Walk This Way". The song appears on Afrika Bambaataa's 1997 compilation album, ''Zulu Groove''. It was arranged by Laswell after Lydon and Bambaataa had acknowledged respect for each others' work, as described in an interview from 1984: |

|||

:Afrika Bambaataa: "I was talking to Bill Laswell saying I need somebody who's really crazy, man, and he thought of John Lydon. I knew he was perfect because I'd seen this movie that he'd made (''Corrupt'', a.k.a. ''Copkiller'' and ''The Order of Death''), I knew about all the Sex Pistols and Public Image stuff, so we got together and we did a smashing crazy version, and a version where he cussed the Queen something terrible, which was never released." |

|||

:John Lydon: "We went in, put a drum beat down on the machine and did the whole thing in about four-and-a-half hours. It was very, very quick."<ref>[http://www.fodderstompf.com/CHRONOLOGY/1984.html 1984 interview]</ref> |

|||

Rutter was secretary of the AAA and organised it for four years. It was artistically accomplished, but not so financially.<ref name=odnb/> Through the AAA, Rutter helped many artists, such as [[Charles Ginner]], who, although not achieving outstanding success, was able to gain an audience and develop a loyal following for his work.<ref>''[[The Times]]'', 7 January 1952, p. 6, Issue 52202, col E, "Mr. Charles Ginner". Retrieved from [http://infotrac.galegroup.com infotrac.galegroup.com], 8 August 2008.</ref> The AAA exhibited also for the first time in London [[Constantin Brâncuşi]], [[Jacob Epstein]], [[Robert Polhill Bevan|Robert Bevan]] and [[Walter Bayes]].<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

The single also featured [[Bernie Worrell]], [[Nicky Skopelitis]] and [[Aïyb Dieng]], all of whom would later play on PiL's ''Album''; Laswell also played bass and produced. |

|||

From October 1909 to 1912,<ref name=whos/> Rutter also published and edited the weekly, cheaply-printed ''Art News'', the journal of the AAA, like which it had an open-door policy on contributors, featuring the lectures given to the [[Royal Academy|Royal Academy Schools]] by Sir William Blake Richmond, as well as Sickert's attack on the Royal Academy, "Straws from Cumberland Market".<ref name=robins/> It was promoted as the "First Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom".<ref name=robins/> |

|||

===Solo album: ''Psycho's Path''=== |

|||

In 1997 Lydon released a solo album on [[Virgin Records]] called ''[[Psycho's Path]]''. He wrote all the songs and played all the instruments. In one song, "Sun", he sang the vocals through a toilet roll.<ref name="ppinfo">{{cite web |

|||

| url= http://www.johnlydon.com/pp/pp_info.html |

|||

|publisher= JohnLydon.com |

|||

| title="''Psycho's Path''"}}</ref> It did not sell particularly well and received mixed reviews from critics. The U.S. version included a [[Chemical Brothers]] remix of the song "Open Up" by [[Leftfield]] with vocals by Lydon. This song is heard during the title menu of the computer game ''All Star Baseball 2000'' ([[Acclaim Entertainment]]). The song was also a club hit in the U.S. and a big hit in England. |

|||

==Suffragettes, Post-Impressionism, and Leeds== |

|||

===Movie, TV and other non-music projects=== |

|||

[[Image:johnlydonbook.jpg|right|thumb|175px|John Lydon's book ''Rotten - No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs'' Picador, 1995. ISBN 0-312-11883-X.]] |

|||

[[Image:Suffragettes, England, 1908.JPG|thumb|[[Suffragettes]] in England, 1908.]] |

|||

====Film==== |

|||

On 30 August 1909 Rutter married Thirz Sarah (Trixie, born 1887/8), whose father, James Henry Tiernan, was a member of the [[New Zealand Police]].<ref name=odnb/> With the encouragement of [[George Bernard Shaw]], Rutter became a member of the [[Fabian Society]].<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

In 1983, Lydon co-starred with [[Harvey Keitel]] in the movie thriller [[Copkiller|''Corrupt'', a.k.a. ''Copkiller'' and ''The Order of Death'']]. While the film was generally panned, Lydon won some praise for his role as a [[psychosis|psychotic]] rich boy. Lydon would act again very occasionally after that, such as a very small role in the 2000 film, ''[[The Independent (film)|The Independent]]''. |

|||

On [[12 January]] [[1910]], at the Eustace Miles Restaurant, Rutter chaired the meeting of a group which developed into the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement,<ref name=crawford>Crawford, Elizabeth. ''The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866-1928'', p. 612, Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415239265, ISBN 9780415239264</ref> of which he was the honorary treasurer.<ref name=bryson>Bryson, Norman; Holly, Ann Michael; Moxey, Keith P. F. ''Visual Culture: Images and Interpretations'', p. 42. Wesleyan University Press, 1994. ISBN 081956267X, ISBN 9780819562678. Retrieved from [http://books.google.co.uk/books?http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Lcq2FK0ALYkC&pg=PA42&vq=rutter&source=gbs_search_r&cad=1_1&sig=ACfU3U1sZKjl81OMabg3tf5pPHHEii3Wew Google books].</ref> Four months later he was the speaker representing the Press at the John Stuart Mill Celebrations, which were staged by the Women's Freedom League.<ref name=crawford/> |

|||

He also was the host of the skateboard film, ''Sorry'', by The Flip Skate Team |

|||

In 1910, [[Roger Fry]] occupied the limelight of [[avant-garde]] campaigning for art, when he outraged the public with an exhibition ''Manet and the post-impressionists'' at the Grafton Galleries, showcasing work by [[Vincent van Gogh|Van Gogh]], [[Paul Gauguin|Gauguin]] and [[Paul Cézanne|Cézanne]].<ref name=odnb/> Rutter had put the term ''Post-Impressionist'' in print in ''Art News'' of [[15 October]] [[1910]], three weeks before Fry's show, during a review of the [[Salon d'Automne]], where he described [[Othon Friesz]] as a "post-impressionist leader"; there was also an advert in the journal for the show ''The Post-Impressionists of France''.<ref name=bullen>Bullen, J. B. ''Post-impressionists in England'', p.37. Routledge, 1988. ISBN 0415002168, ISBN 9780415002165</ref> |

|||

====Radio==== |

|||

In the mid-1990s, Lydon hosted ''Rotten Day'', a daily syndicated US radio feature written by [[George Gimarc]]. The format of the show was a look back at events in popular music and culture occurring on the particular broadcast calendar date about which Lydon would offer cynical commentary. The show was originally developed as a radio vehicle for Gimarc's book, ''Punk Diary 1970-79'', but after bringing Lydon onboard it was expanded to cover notable events from most of the 2nd half of the 20th century. |

|||

Rutter quickly supported Fry's venture with a small book ''Revolution in Art'' (enlarged in 1926 as ''Evolution in Modern Art''), its title derived from Gauguin's statement that "in art there are only revolutionists or plagiarists."<ref name=odnb/> Rutter wrote in the dedication: "To Rebels of either sex all the world over who in any way are fighting for freedom of any kind I dedicate this study of their painter-comrades."<ref name=bryson/> |

|||

====Television==== |

|||

=====Judge Judy===== |

|||

In November 1997, Lydon appeared on ''[[Judge Judy]]'' fighting a suit filed by his former tour drummer Robert Williams for breach of contract, and [[assault and battery]]. Lydon won the case, and the judge called Williams a ''"[[nudnik]]"'', although she did advise Lydon to keep quiet several times. During an appearance on ''[[Politically Incorrect]]'', in response to a statement about "hand lotion" in men's restrooms, Lydon remarked "Well, ''I'm'' English - ''we'' still have our foreskins". |

|||

On [[25 March]] [[1911]], Rutter chaired a meeting of the Men's Political Union at [[Caxton Hall]], [[Westminster]], and reported that a recent court case at Leeds, in which Alfred Hawkings had been awarded £100 damages for being ejected from a meeting, was "a distinct victory for the suffragist cause." Rutter roused cheers from his listeners upon exhorting them that they needed to prove to their opponents that "the reign of bullying, tyranny, and savagery must come to an end."<ref>''[[The Times]]'', 27 March 1911, p. 6, issue 39543, col F, "Woman Suffrage. The Interruption Of Public Meetings." Retrieved from [http://infotrac.galegroup.com infotrac.galegroup.com], 8 August 2008.</ref> |

|||

=====Rotten TV===== |

|||

In 2000, Lydon hosted ''Rotten TV'', a short-lived show on [[VH1]]. The show offered his acerbic commentary on American politics and pop culture. In one segment he took [[Neil Young]] to task for not appearing on the show, making fun of Young's singing style and pointing out that Young had once proclaimed Johnny Rotten "the king" in the song "[[Hey Hey, My My (Into The Black)]]". It was good natured, however, as Rotten has been quoted to proclaim his love of Young's albums ''[[On the Beach (album)|On the Beach]]'' and ''[[Tonight's the Night (album)|Tonight's the Night]]''. |

|||

Rutter's ''Art News'' reported on the AAA show of July 1911 and also printed the Futurist Painters Manifesto (first printed as the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in February 1909 in ''[[Le Figaro]]'').<ref>Yeates, p.122</ref> In April 1912, because of financial difficulties,<ref name=odnb/> Rutter resigned as secretary of the AAA, which had been strongly supported by [[Lucien Pissarro]], [[Walter Sickert]] and others, but which he felt was nevertheless dwindling away due to what he condemned as "the incurable snobbishness of the English artist".<ref name=obit/> That year he relocated from London to [[Leeds]] for the next five years, having been appointed curator of the [[Leeds City Art Gallery]] at a salary of £300 per annum.<ref name=taylor/><ref name=odnb/> He continued to advocate new ventures in art through his column "Round the galleries" in ''The Sunday Times''.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

=====The Belzer Connection===== |

|||

In 2003 Lydon appeared as a panelist on an episode of [[Richard Belzer]]'s ambitious (and ill-fated) [[conspiracy]]-themed panel show, ''The Belzer Connection''. The episode in question posed the query, "Was there a conspiracy involved in the death of [[Princess Diana]]?" For his part, Lydon proved as witty and scurrilous as ever, responding to suggestions of [[Royal Family]] involvement by proclaiming "If the Royal Family was going to assassinate someone, they would have gotten rid of me a long time ago." The series ran for only two episodes. |

|||

[[Image:Leeds-City-Art-Gallery-1888.jpg|thumb|Opening of Leeds City Art Gallery in 1888 from the ''[[The Illustrated London News]]''.]] |

|||

=====I'm A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here===== |

|||

He used his house at 7 Westfield Terrace, [[Chapel Allerton]], Leeds, to provide accommodation for [[suffragette]]s released from prison under the [[Cat and Mouse Act]] and recovering from [[hunger strike]].<ref name=crawford/> In 1913, he provided a character reference so that a job could be obtained in Europe by a "mouse", [[Elsie Duval]]; another, [[Lilian Lenton]], a suffragette [[arson|arsonist]] also escaped via his home to France in June that year with the aid of his wife.<ref name=crawford/><ref name=odnb/> Elizabeth Crawford, author of ''The Women's Suffrage Movement'', suggests that other similar events must have taken place, but were kept quiet at the time out of necessity and, later, due to Rutter's taciturnity.<ref name=crawford/> He wrote in an epilogue to his autobiography: |

|||

In January 2004, Lydon appeared on the British [[reality television]] programme, ''[[I'm a Celebrity... Get Me out of Here! (UK)|I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here!]]'', which took place in Australia. He proved he still had the capability to shock by calling the show's viewers "fucking cunts" during a live broadcast. The television regulator and [[ITV]], the channel broadcasting the show, between them received 91 complaints about Lydon's use of bad language. However, in a February 2004 interview with the Scottish ''[[Sunday Mirror]]'', Lydon said that he and his wife "should be dead", since on 21 December 1988, thanks to delays caused by his wife's packing, they missed the doomed [[Pan Am Flight 103]].<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/Lockerbie/Story/0,2763,1154000,00.html Sex Pistol recounts Lockerbie near miss | UK news | The Guardian<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> During this interview, Lydon said that the real reason for him leaving the ''Get Me Out of Here!'' show was his fear over the Pan Am incident and the "appalling" refusal of the programme makers to let him know whether his wife had arrived safely in Australia. |

|||

:the only furiously active part of my life was the few years during which I was connected with the militant suffrage movement and of this I have said nothing, because if I once began I should want to fill a volume with my experiences during this exciting time. It is all over now, the battle has been won, and this is not the place in which to recount the skirmishes in which I had the honour to take part."<ref name=crawford/> |

|||

He did not agree with the later, more extreme tactics of the [[WSPU]] leaders, who nevertheless still commanded his respect and admiration.<ref name=crawford/> He encouraged the artist, [[Emily Susan Ford]] (1850-1930), Vice-Chairman of the Artists' Suffrage League and exhibited her work in the Leeds gallery.<ref>Crawford, pp. 225-226.</ref> |

|||

In an interview previous to the show's first episode, he had described it as "moronic", and throughout the show's run he had displayed an indifferent attitude to staying and threatened to walk out on numerous occasions. 30 hours following ex-[[Football (soccer)|football]] star [[Neil Ruddock]]'s departure, Lydon left the show for unclear reasons, although he had been very visibly angry both to and about fellow star [[Jordan (Katie Price)|Jordan]]. |

|||

Rutter initially had plans to create a modern art collection at the Leeds gallery, but had been frustrated in this aim by "boorish" local councillors; his association with the escape of Lilian Lenton had further damaged his standing.<ref name=odnb/> Before he left the city, he co-founded the Leeds Art Collections Fund with Michael Sadler, who was the vice-chancellor of [[Leeds University]] and a collector of work by Kandinsky and [[Paul Gauguin|Gauguin]].<ref name=odnb/> The Fund helped with acquisitions and shows, among them the first major [[John Constable]] show and another in June 1913 of [[Post-Impressionism]] held at the [[Leeds Arts Club]], which had been started by Holbrook Jackson and A. R. Orage, editor of ''[[The New Age]]'', and was galvanised by the new activity.<ref name=odnb/> The discussions there about contemporary art had a significant influence on the thinking of [[Herbert Read]] (1893–1968),<ref name=odnb/> who was introduced to modern art by Rutter.<ref name=saler/> Rutter's plan for a literary version of the AAA had a strong appeal for Read.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

British newspapers claimed that Lydon had won a [[£]]100 bet with Ruddock over who would stay in the longest. Lydon, however, stated on air that he felt he would win outright and that it would be unfair to the other celebrities for him to win. |

|||

==Futurism== |

|||

=====John Lydon's Megabugs, Goes Ape and Shark Attack===== |

|||

[[Image:Bevan-Cabyard.jpg|thumb|[[Robert Bevan]]. ''The Cabyard, Night''.]] |

|||

After ''I'm a Celebrity...'', he presented a documentary about [[insects]] and [[spider]]s called ''John Lydon's Megabugs'' that was shown on the [[Discovery Channel]]. <ref name=Johnny be good> |

|||

In October 1913, Rutter was commissioned by the [[Doré Gallery]] at 35 [[Bond Street]] in the [[West End of London|West End]] to curate the ''Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition'', which displayed the story of those movements from [[Camille Pissarro]] to [[Vorticism|Vorticist]] [[Wyndham Lewis]] (who was no longer on good terms with Fry).<ref name=odnb/> Rutter's choice of Pissarro as a starting point was in contradistinction to the stance of Fry and the [[Bloomsbury Group]], who saw Cézanne as the beginning of modern art.<ref name=yeates125>Yeates, p.125</ref> |

|||

{{cite news |

|||

| title = The Sex Pistols: Johnny be good? Never! |

|||

| work = Telegraph.co.uk |

|||

| date = 2007-11-8 |

|||

| url = http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2007/11/08/bmlydon108.xml |

|||

| accessdate = 2008-07-26 |

|||

}}</ref> ''[[Radio Times]]'' described him as "more an enthusiast than an expert". He went to present two further programmes: ''John Lydon Goes Ape'' in which he searched for [[gorilla]]s in [[Central Africa]], and ''John Lydon's Shark Attack'' in which he swam with [[shark]]s off South Africa. |

|||

Rutter made a link between the British artists he supported and the French [[Intimistes|intimiste]] painters, as well as featuring artworks by [[Gino Severini|Severini]] and [[Umberto Boccioni|Boccioni]] of the Italian [[Futurism]] movement, which had been shown in London first by the [[Sackville Gallery]].<ref name=yeates125/> Rutter's consummate curation and catalogue foreword were a testament to his deep knowledge of the subject.<ref name=odnb/> He praised [[Christopher R.W. Nevinson|Nevinson]]'s ''The Departure of the Train De Luxe'' as "the first English [[Futurism|Futurist]] picture".<ref>Walsh, Michael. ''[[Apollo (magazine)|Apollo]]'', February 2005, "Vital English art: futurism and the vortex of London 1910-14". Retrieved from [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0PAL/is_516_161/ai_n13592228/pg_2?tag=untagged findarticles.com], 8 August 2008.</ref> |

|||

=====Reynebau & Rotten===== |

|||

In 2005, he appeared in ''Reynebeau & Rotten'', a five episode documentary on [[Canvas TV Station|Canvas]], the cultural channel of [[VRT]], which is the [[Flanders|Flemish]] public broadcaster. Lydon guided Belgian journalist Marc Reynebeau through Great Britain. When asked why he was chosen as a guide, he answered that he was the cheapest one available. |

|||

Also in 1913, ''The Cabyard, Night'', the only painting by [[Robert Bevan]] (1865–1925) acquired for a public collection during the artist's lifetime, was bought by the [[Contemporary Art Society]] on Rutter's recommendation that they should obtain it for the nation before a more discerning collector bought it.<ref>[http://www.virtualmuseum.info/art/ag_20th/bevan.asp "Art catalogue: Robert Bevan (1865-1925)"], Brighton and Hove Museums. Retrieved 8 August 2008.</ref> |

|||

After the show had been broadcast on Flemish television, Lydon claimed in an interview with the popular Belgian magazine ''[[HUMO]]'' that he was very unhappy with the way they handled post-production and was very angry with the way they depicted him in this particular show. He claimed that the creators mainly showed his humorous, sometimes clownish antics, instead of focusing on his personal opinions and sometimes philosophical conversations he had with Marc Reynebeau. Lydon was also infuriated that the production company used songs from the Sex Pistols' catalogue, without consulting all the remaining members of the band, including him. |

|||

==''Arts and Letters''== |

|||

Lydon broadcast a short pod on [[Current TV]] in which he critiqued [[The Doors]]' keyboardist [[Ray Manzarek]]'s previously broadcast pod. Manzarek's advice to young people had been to "fuck your brains out." He emphasized this especially for 25-year- old women, saying that "it won't last." Lydon had several choice words for Manzarek and told young people that the best thing they could do was get an education because knowledge is free. Lydon also suggested that at one point Manzarek had asked him to work on a project together and that he did not do it because it would negatively affect his career. |

|||

Rutter, along with [[Harold Gilman]] and [[Charles Ginner]] had planned the launch of a journal, ''Arts and Letters'', for Spring 1914, but this was delayed by the outbreak of [[World War I|war]].<ref>Robins gives Gilman's death in 1917 as contributory to the publication delay. However, Gilman died in 1919 (''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'').</ref><ref name=robins/> It began publication in July 1917 as an illustrated quarterly,<ref name=AL>''Arts and Letters'', Vol. 1, No. 1, July 1917, "Contents".</ref> co-edited by Rutter and [[Herbert Read]],<ref>Aldington gives Ginner and Gilman as co-editors with Rutter.</ref> whose aesthetic and critical ideas dominated.<ref name=robins/><ref name=aldington>Aldington, Richard; H.D. (Doolittle, Hilda); Zilboorg, Caroline. ''Richard Aldington & H.D.: Their Lives in Letters'', p. 157, Manchester University Press, 2003. ISBN 0719059720, ISBN 9780719059728.</ref> It was a modernist magazine of visual and literary art, which fused the artistic and the political.<ref name=saler>Saler, Michael T. ''The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground'', p. 52, Oxford University Press US, 1999. ISBN 0195119665, ISBN 9780195119664.</ref> |

|||

Lydon is currently one of the judges in the [[Bodog]] Music Battle of The Bands competition. |

|||

The contents page of the first issue carried a policy of renumeration for contributors, based on "co-operative lines" that after the cost of production and 5% on capital, half of the profits would go to editorial and publishing staff and the other half would be split equally between contributors.<ref name=AL/> Underneath an 1894 woodcut by [[Lucien Pissarro]], page one carried an editorial explaining the delayed publication due to the outbreak of war and justifying the use of scarce materials, compared to other periodicals "which give vulgar and illiterate expression to the most vile and debasing sentiments."<ref name=AL1>''Arts and Letters'', Vol. 1, No. 1, July 1917, p. 1.</ref> It was also stated that some of the contributors were serving at the front and that educated men in the army were keen to see such a publication: "Engaged, as their duty bids, on harrowing work of destruction, they exhort their elders at home never to lose sight of the supreme importance of creative art."<ref name=AL1/> |

|||

=====Country Life butter advert===== |

|||

In September 2008, it was announced that Lydon would appear in an advert for [[Country Life]], a popular brand of butter, in a move Lydon was widely mocked for. [http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-1050489/One-anarchist-Johnny-Rotten-turns-country-squire-TV-butter-ad.html] [http://www.thetartpaper.com/ents.php?id=1413] |

|||

Sickert's "Thérèse Lassore" was printed in 1918, after which the journal ceased publication for a year. It resumed again with [[Osbert Sitwell]] as Rutter's co-editor—and [[T. S. Eliot]]'s theories predominating editorially—but folded in 1920.<ref name=aldington/> |

|||

==Controversy== |

|||

=== The Ritz Carlton Hotel case === |

|||

On 23 January 2008 Lydon was reportedly involved in a string of offences, including [[battery (crime)|battery]], [[sexual abuse]], [[sexual assault]] and [[physical assault]]. Ms Davis (Lydon's employer on his television program) was punched in the face by Lydon after being called a "cunt" several times. It is believed that Lydon wished for a door between his hotel room and his male friend's room at the hotel [[Ritz Carlton]], but was given a separate room without a dividing door. Lydon reportedly became infuriated with the hotel staff, before assaulting his own employee who was staying in the same hotel. Upon being questioned by journalists over the incident, Lydon was unavailable. Davis has taken legal action against Lydon, her lawsuit is underway in a San Francisco court room <ref>http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/music/news/exsex-pistol-lydon-sued-for-lsquoassault-and-batteryrsquo-13507701.html</ref>. |

|||

From 1915 to 1919, Rutter returned to the Allied Artists' Association in the guiding role of chairman.<ref name=odnb/><ref>''[[Who Was Who]]'' says he returned to the AAA 1915–1922.</ref> In 1917, he resigned his job at the Leeds City Art Gallery,<ref name=odnb/> and he worked for the Admiralty as an administrative officer (AAO) until 1919.<ref name=whos/> |

|||

=== 2008 Summercase incident === |

|||

[[Bloc Party]] singer [[Kele Okereke]] claims he was left with severe facial bruising and a split lip following what he alleges was a verbal and physical racist assault by three members of Lydon's entourage. The incident occurred on the evening of 19 July 2008 at the [[Summercase]] festival in [[Barcelona]] while the bands were socialising backstage. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/jul/22/john.lydon.racist.assault] |

|||

==1920s and 1930s== |

|||

However in statement to [[NME]], John Lydon has denied the allegations of his involvement in this assault. <ref>[http://www.nme.com/news/bloc-party/38378 'Kele Okereke was right about Sex Pistols racist attack' | News | NME.COM<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Since the report, [[Super Furry Animals]] lead singer [[Gruff Rhys]] has come forward in support of Okereke's claim, saying "the statements Kele has said are absolutely true, it did happen." <ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2008/jul/24/gruff.rhys.supports.okereke Gruff Rhys supports Kele Okereke's account of racial abuse | Music | guardian.co.uk<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

[[Image:London Underground WWI poster.jpg|thumb|[[London Underground]] poster, 1915.]] |

|||

A British tabloid accused Lydon of racism due to the incident. Lydon strongly denied these claims on ''[[The One Show]]'', claiming that they were "atrocious" and "hurtful". he went on to say that: |

|||

After leaving the Admirality, Rutter opened the [[Adelphi Gallery]] to exhibit small pieces by Ginner, [[Edward Wadsworth]] and [[David Bomberg]].<ref name=odnb/> Finding this a restriction on his "liberty and leisure" he returned to writing and completed in the region of 20 books, as well as a considerable number of contributions to ''[[The Burlington Magazine]]'', ''[[Apollo (magazine)|Apollo]]'', ''[[Studio Magazine]]'', ''[[The Financial Times]]'' and ''[[The Times]]''.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

{{cquote2|My grand children are Jamaican, right. This is an absolute offence to them and me when I read stories like that, that are allowed to go to print absolutely unfounded and have the liberty to take liberties with a man like me and call me a racist when my entire life has proved exactly the opposite.}} |

|||

In his writings he emphasised both the spiritual and social role of art.<ref name=saler/> He also commented on the visual power to be found in the [[London Underground]]: "The whole nation is much less affected by what pictures are shown in the Royal Academy than by what posters are put up on the hoardings.<ref>British English for ''[[billboard]]''</ref> A few thousand see the first, but the second are seen by millions. The art galleries of the People are not in Bond Street but are to be found in every railway station."<ref>Saler, pp. 101-102.</ref> |

|||

He went on to say, when asked if he was racist, that: |

|||

On 28 March 1920 in ''[[The Sunday Times]]'', Rutter reviewed the short-lived [[Group X (art)|Group X]] (a reforming of the [[Vorticism|Vorticists]]), "the real tendency of the exhibition is towards a new sort of realism, evolved by artists who have passed through a phase of abstract experiment.".<ref name=x>"Group X", [[Grove Dictionary of Art|Grove Art Online]], retrieved from [http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T035139?q=frank+rutter&search=quick&pos=4&_start=1#firsthit Oxford Art Online] (subscription site), 8 August 2008.</ref> |

|||

{{cquote2|Absolutely not. And any bugger that dares say so is going to have their day in court with me - you understand this?<ref>[http://www.digitalspy.co.uk/showbiz/a116667/lydon-threatens-legal-action-over-racism-row.html]</ref>}} |

|||

He divorced his wife around this time, and on [[29 March]] [[1920]] married Ethel Dorothy (born 1894/5), the second daughter of William Robert Bunce, a coal merchant.<ref name=odnb/> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

Lydon is married to Nora Forster. They have no children together, but Lydon is [[stepfather]] of Forster's daughter, [[Ari Up]], who herself had been the lead singer in the influential [[postpunk]], [[dub reggae]] band, [[The Slits]]. He currently lives in Los Angeles.<ref name="Telegraph">{{cite web| url= http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2007/11/08/bmlydon108.xml| title=Daily Telegraph feature interview, 8 November 2007}}</ref> |

|||

In 1927, he said of [[Newlyn]] artist [[Dod Proctor]]'s painting, ''Morning'', exhibited in the [[Royal Academy]] that it was "a new vision of the human figure which amounts to the invention of a twentieth century style in portraiture"<ref>King, Averil. ''[[Apollo (magazine)|Apollo]]'', "An exotic awakening", 1 January 2006. Retrieved from [http://www.findarticles.com findarticles.com] (registration required), 8 August 2008.</ref> and "She has achieved apparently with consummate ease that complete presentation of twentieth century vision in terms of plastic design after which [[André Derain|Derain]] and other much praised French painters have been groping for years past."<ref name=lang>Lang, Elsie M. ''British Women in the Twentieth Century'', Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0766161153, ISBN 9780766161153</ref> |

|||

==Discography== |

|||

All chart positions are UK. |

|||

===Sex Pistols=== |

|||

'''Studio albums''' |

|||

* ''[[Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols]]'' (Virgin, 1977) Platinum |

|||

1928–1931, Rutter was European Editor of ''International Studio'', New York.<ref name=whos/> He was also the London Correspondent for the Association Française d’Expansion et d’Echanges Artistiques.<ref name=whos/> In 1932, he praised advances in the [[Tate|Tate Gallery]]'s attitude towards art since its foundation (although others, notably [[Douglas Cooper (critic)|Douglas Cooper]], considered it "hopelessly insular").<ref>Spalding, Frances (1998). ''The Tate: A History'', pp. 65–66. Tate Gallery Publishing, London. ISBN 1 85437 231 9.</ref> |

|||

'''Compilations and live albums''' |

|||

* ''[[The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle#Soundtrack|The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle]]'' (Virgin, 1979) |

|||

* ''Some Product: Carri On Sex Pistols'' (Virgin, 1979) |

|||

* ''Kiss This'' (Virgin, 1992) |

|||

* ''Never Mind the Bollocks / [[Spunk (Sex Pistols album)|Spunk]]'' (aka ''This is Crap'') (Virgin, 1996) |

|||

* ''Filthy Lucre Live'' (Virgin, 1996) |

|||

* ''The Filth and the Fury'' (Virgin, 2000) |

|||

* ''Jubilee'' (Virgin, 2002) |

|||

* ''Sex Pistols Box Set'' (Virgin, 2002) |

|||

He suffered from a [[bronchial]] complaint for a number of years, as a result of which he periodically sojourned on the [[Southern England|South Coast]], visiting London exhibitions when he felt in good enough health to do so.<ref name=obit/> In April 1937, he had an attack of [[bronchitis]] and died, aged 61, a fortnight later on 18 April in his home at 5 Litchfield Way, [[Golders Green]], [[London]];<ref name=obit/> the funeral service was at 12.30 p.m. on 21 April at Golders Green Crematorium.<ref>''[[The Times]]'', 20 April 1937, p. 1, Issue 47663, col B, "Deaths". Retrieved from [http://infotrac.galegroup.com infotrac.galegroup.com], 10 October 2008.</ref> He wrote his ''Sunday Times'' article up to a week before his death.<ref name=obit/> He left his estate, which included around 80 paintings by the likes of Gilman, Ginner, Gore and Lucien Pissarro, to his wife.<ref name=odnb/> He had no children.<ref name=obit/> |

|||

'''Singles''' |

|||

* "[[Anarchy in the UK]]" - 1976 #38 |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:Gstq.PNG|thumb|right|The cover of the ''God Save the Queen'' single. It was designed by [[Jamie Reid]] in the ransom note style that came to be associated with the Sex Pistols.]] --> |

|||

* "[[God Save the Queen (Sex Pistols song)|God Save the Queen]]" - 1977 #2 |

|||

* "[[Pretty Vacant]]" - 1977 #6 |

|||

* "[[Holidays in the Sun]]" - 1977 #8 |

|||

* "[[(I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone|(I'm Not Your) Stepping Stone]]" - 1980 #21 |

|||

* "[[Anarchy in the UK]]" (re-issue) - 1992 #33 |

|||

* "[[Pretty Vacant]]" (live) - 1996 # 18 |

|||

* "[[God Save the Queen (Sex Pistols song)|God Save the Queen]]" (re-issue) - 2002 # 15 |

|||

==Appearance and character== |

|||

===Public Image Ltd.=== |

|||

'''Studio albums''' |

|||

* ''[[First Issue]]'' (Virgin, 1978) |

|||

* ''[[Metal Box]]'' (Virgin, 1979) |

|||

* ''[[Flowers of Romance (album)|Flowers of Romance]]'' (Virgin, 1981) |

|||

* ''[[Commercial Zone]]'' (PiL Records, 1983) |

|||

* ''[[This Is What You Want... This Is What You Get]]'' (Virgin, 1984) |

|||

* ''[[Album (Public Image Limited album)|Album]]'' (Virgin, 1986) |

|||

* ''[[Happy? (Public Image Limited)|Happy?]]'' (Virgin, 1987) |

|||

* ''[[9 (Public Image Limited album)|9]]'' (Virgin, 1989) |

|||

* ''[[That What Is Not]]'' (Virgin, 1992) |

|||

Rutter was tall with an incisive profile, an enthusiastic character and a strong manner of delivery. He was a supportive friend and good company who injected conversations with humour, for which he adopted an "uncular" manner.<ref name=obit/> He was modest and generous, not motivated by personal ambition, but advancing the interests of art and artists over any profit for himself.<ref name=yeates85/> His approach was not that of an intellectual applying logic impersonally, but through aesthetic intuition and an empathy for the creative process.<ref name=yeates85/> His knowledge of art history sufficed for his needs, and he could be critical, but his main feature was the display of personal judgement and a prefence to address the work he could enjoy.<ref name=obit/> |

|||

'''Compilations and live albums''' |

|||

* ''Second Edition EP'' (Virgin, 1980) |

|||

* ''Paris in the Spring (Paris au Printemps)'' (Virgin, 1980) |

|||

* ''[[Live in Tokyo (Public Image Ltd.)|Live in Tokyo]]'' (Virgin, 1983) |

|||

* ''[[The Greatest Hits, So Far]]'' (Virgin, 2003) |

|||

==Books== |

|||

'''Singles''' |

|||

* "Public Image" - 1978 #9 |

|||

* "[[Death Disco]]" - 1979 #20 |

|||

* "Memories" - 1979 #60 |

|||

* "Flowers of Romance" - 1981 #24 |

|||

* "This Is Not a Love Song" - 1983 #5 |

|||

* "Bad Life" - 1984 #71 |

|||

* "Rise" - 1986 #11 |

|||

* "Home" - 1986 #75 |

|||

* "Seattle" - 1987 #47 |

|||

* "The Body" - 1987 #100 |

|||

* "Disappointed" - 1989 #38 |

|||

* "Don't Ask Me" - 1990 #22 |

|||

* "Cruel" - 1992 #49 |

|||

<ref name=whos/> |

|||

===Time Zone=== |

|||

* ''Varsity Types'', 1902 |

|||

'''Single''' |

|||

* ''The Path to Paris'', 1908 |

|||

* "[[World Destruction]]" - 1984 |

|||

* ''Rossetti, Painter and Man of Letters'', 1909 |

|||

* ''Whistler, a Biography and an Estimate'', 1910 |

|||

* ''Revolution in Art'', 1910 |

|||

* ''The Wallace Collection'', 1913 |

|||

* ''Some Contemporary Artists'', 1922 |

|||

* ''The Poetry of Architecture'', 1923 |

|||

* ''Richard Wilson and Farington'', 1923 |

|||

* ''The Old Masters'', 1925 |

|||

* ''Evolution in Modern Art'', 1926 |

|||

* ''Theodore Roussel'', 1927 |

|||

* ''Since I was Twenty-Five'', 1928 |

|||

* ''El Greco'', 1930 |

|||

* ''Art in My Time'', 1933 |

|||

* ''Modern Masterpieces'', 1936 |

|||

== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Leeds Arts Club]] |

|||

'''Studio albums''' |

|||

* ''[[Psycho's Path]]'' (Virgin, 1997) |

|||

==Notes and references== |

|||

'''Compilations''' |

|||

* ''[[The Best of British £1 Notes]]'' (Lydon, PiL & Sex Pistols) (Virgin/EMI, 2005) |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

'''Singles''' |

|||

* "[[Open Up (song)|Open Up]]" (with [[Leftfield]]) – 1993 – #11 UK |

|||

* "Sun" – 1997 – #42 UK |

|||

==Footnotes== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

<http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/music/news/exsex-pistol-lydon-sued-for-lsquoassault-and-batteryrsquo-13507701.html/> |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wikiquote}} |

|||

* [http://www.johnlydon.com Official John Lydon website] |

|||

* [http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/manuSCRIPTs/search/resultsn.cfm?NID=228&RID= Letters at the University of Glasgow relating to Frank Rutter] |

|||

* [http://youtube.com/watch?v=p2CnwYPhcQk Johnny Rotten on Judge Judy !] |

|||

* [http://www.youtube.com/rottentv RottenTube] |

|||

* [http://www.johnlydon.com/pp/pp_index.html Psycho's Path Micro-Site] |

|||

* [http://www.johnlydon.com/notes/notes_index.html The Best of British £1 Notes Micro-Site] |

|||

* [http://www.cbc.ca/thehour/video.php?id=1483 Johnny Rotten on The Hour] |

|||

------ |

|||

{{Sex Pistols}} |

|||

* [http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/music/news/exsex-pistol-lydon-sued-for-lsquoassault-and-batteryrsquo-13507701.html] |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

|NAME=Lydon, John Joseph |

|||

|ALTERNATIVE NAMES=Johnny Rotten |

|||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION=English rock musician |

|||

|DATE OF BIRTH=31 January 1956 |

|||

|PLACE OF BIRTH=[[Holloway]] in London, England |

|||

|DATE OF DEATH= |

|||

|PLACE OF DEATH= |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lydon, John}} |

|||

[[Category:1956 births]] |

|||

[[Category:English songwriters]] |

|||

[[Category:English male singers]] |

|||

[[Category:English punk rock singers]] |

|||

[[Category:Living people]] |

|||

[[Category:People from London]] |

|||

[[Category:Sex Pistols members]] |

|||

[[Category:Public Image Ltd. members]] |

|||

[[Category:Participants in British reality television series]] |

|||

[[Category:Pigface members]] |

|||

[[Category:British people of Irish descent]] |

|||

[[Category:British expatriates in the United States]] |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rutter, Frank}} |

|||

[[ca:John Joseph Lydon]] |

|||

[[Category:English art critics]] |

|||

[[cs:Johnny Rotten]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:British curators]] |

||

[[Category:Old Merchant Taylors]] |

|||

[[de:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[Category:Alumni of Queens' College, Cambridge]] |

|||

[[et:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[Category:The Sunday Times people]] |

|||

[[es:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:1876 births]] |

||

[[ |

[[Category:1937 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:People from Putney]] |

|||

[[gl:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[ko:존 라이든]] |

|||

[[is:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[it:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[he:ג'ון ליידון]] |

|||

[[sw:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[lmo:Johnny Rotten]] |

|||

[[nl:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[ja:ジョン・ライドン]] |

|||

[[no:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[nds:Johnny Rotten]] |

|||

[[pl:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[pt:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[ru:Лайдон, Джон]] |

|||

[[sk:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[sl:John Lydon]] |

|||

[[fi:Johnny Rotten]] |

|||

[[sv:Johnny Rotten]] |

|||

[[tr:John Lydon]] |

|||

Revision as of 12:47, 12 October 2008

Frank Rutter | |

|---|---|

Cover of Arts and Letters, Spring 1920, co-edited by Frank Rutter | |

| Born | 17 February 1876 |

| Died | 18 April 1937 |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | Francis Vane Phipson Rutter |

| Occupation(s) | Art critic, curator |

| Known for | Promoting Impressionism in Britain |

Francis Vane Phipson Rutter (17 February 1876 – 18 April 1937)[1] was a British art critic, curator and activist.

In 1903, he became art critic for The Sunday Times, a position which he held for the rest of his life.[2][3] He was an early champion in England of modern art, founding the French Impressionist Fund in 1905 to buy work for the national collection,[4][1] and in 1908 starting the Allied Artists' Association to show "progressive" art,[5] as well as publishing its journal, Art News, the "First Art Newspaper in the United Kingdom".[6] In 1910, he began to actively support women's suffrage, chairing meetings, and giving sanctuary to suffragettes released from prison under the Cat and Mouse Act—helping some to leave the country.[7]

From 1912 to 1917, he was the curator of Leeds City Art Gallery.[2] In 1917, he edited the cultural journal, Arts and Letters, with Herbert Read.[8] In his writing after World War I, Rutter observed that advertising imagery was seen by far more people than work in art galleries;[9] he noted a new realism after the period of "abstract experiment";[10] and he praised the work of Dod Proctor as a "complete presentation of twentieth century vision".[11]

Early life

Frank Rutter was born at 4 The Cedars, Putney, London, the youngest son of Emmeline Claridge Phipson and Henry Rutter (died 1896).[12] His grandfather, John, and his father were both prosperous solicitors with chambers in Cliffords Inn, Holborn, and both had acted for John Ruskin, John assisting on Ruskin's marriage nullification with Euphemia (Effie) Gray; Henry severed the connection with Ruskin, after the latter rejected his counsel on a property transaction.[13]

From 1889, Frank Rutter was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School, at that time in Aldersgate, where he specialised in Hebrew (under the influence of his father whose hobby was Biblical archaeology)[2] and where pupils were expected to gain Oxbridge scholarships or exhibitions in classics: Rutter, aged seventeen tried but failed to gain a scholarship in history at Exeter College, Oxford, but was successful in the Queen's College, Cambridge, examination for a scholarship in Hebrew,[13] going to university in 1896 and gaining the Semitic Language Tripos (degree) in 1899.[2]

Whilst still at school, Rutter, along with a fellow sixth form student, Edgar D., explored London nightlife, visiting music halls, eating out in Gatti's Restaurant and joining nightclubs, which were then an adjunct to the more formal London's gentleman's club, providing a dining room, ballroom, writing room, and female membership, which was not taken up by respectable women in society, although the male membership was mostly respectable; Rutter's father happily financed these activities.[13]

When at Cambridge, Rutter gained popularity through his banjo-playing,[2] and, thanks to the good train service available, extended his social pursuits to Paris, first visiting in 1898, speaking French fluently and often staying for a month at a time in the city,[13] where he made friends in the Latin Quarter.[2]

After university, spent a few months as an itinerant tutor, then began as a freelance writer in London with a newly acquired typewriter.[2] One of his successful interviews was with Bernard Shaw on the subject of housing problems—the text of which was entirely provided by Shaw himself; The Times printed an interview with the American scout, Major Burnham, recently returned from South Africa.[2]

He obtained posts as assistant editor of To-day and the Sunday Special, both part of the same publishing group. In February 1901, he became sub-editor of the Daily Mail, and began to write art criticism, mostly for The Financial Times and the The Sunday Times.[2][1] In 1902, he went back to To-day as editor for two years, and for a short time brought it back into profit, until it succumbed to cheaper competition and was merged with London Opinion.[2][1] In 1903, Leonard Rees appointed him art critic of The Sunday Times, a post he held for the rest of his life, 34 years in all.[2][12] Rutter honed his skills whilst doing the job, and also made the acquaintance of leading artists in Paris through frequenting the cafés.[12]

The French Impressionist Fund

In 1903 the creation of the National Art Collections Fund initiated many years of frustration for Rutter, who believed it would siphon off available money from his own aims.[14] He was a strong supporter of Impressionist and Expressionist Modernism.[15][4] He considered "perfectly dreadful"[16] the lack of such work in the national collections, pointing out in 1905 that the only example of the modern French school was Edgar Degas' The Ballet from Robert the Devil (1876) in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[4]

Raging with indignation, he wrote articles on this omission, gave lectures,[16] and, galvanised by the opening of the Impressionist exhibition staged by Durand-Ruel at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1905,[4] he persuaded the editor and proprietors of The Sunday Times to allow space for a public subscription, the French Impressionist Fund.[16] Sargent and Wertheimer each sent ten guineas; Blanche Marchesi staged a fund-raising concert; Rutter, although "extremely nervous" gave his first lecture at the Grafton Galleries.[16] Sir Claude Phillips and D.S. MacColl joined him on the executive committee of the fund, and contributions slowly mounted up to £160, sufficient at that time to buy a top class Impressionist painting.[16]

Rutter's choice was Monet's Vétheuil: Sunshine and Snow (since retitled Lavacourt under Snow), which MacColl was in favour of and Durand-Ruel had promised to sell for the amount collected, but Phillips pointed out that National Gallery did not accept work by living artists; discreet enquiries revealed that the gallery trustees also found too "advanced" Manet, Sisley and Pissarro: "They were certainly dead—but they had not been dead long enough for England", wrote Rutter, adding "I nearly wept with disappointment."[16]

MacColl ascertained that the trustees would accept Eugène Boudin, who Rutter protested was not an Impressionist but whom he accepted out of necessity, mollified by MacColl's argument that "he's the beginning of Impressionism and we can make a start with him."[16] To avoid any accusations of logrolling Durand-Ruel's exhibition, they agreed that Rutter would travel to Van der Veldt, a private collector in Havre, to choose a Boudin painting. He brought back as personal luggage Boudin's 1888 painting, Entre les jetées, Trouville (The Entrance to Trouville Harbour),[17][16] and wrote to MacColl on 11 October 1905 to inform him of the work he had selected, which Van der Veldt had accepted £120 for provided it would go to a national collection, and which was waiting at the Goupil Gallery for MacColl to see.[18]

It was shown privately at the Goupil Gallery for the subscribers, and presented in January 1906 to the National Gallery through the National Art Collections Fund, which Rutter said was keen to act as a channel for the prestigious presentation, but had not given "the slightest help or encouragement when I needed it most."[16] It made Rutter "boil with rage" to contrast this with the Fund's spending of thousands of pounds on older paintings; he said, "the Fund's inertia and snobbish ineptitude are entirely characteristic of the art-officialdom in England."[16]

Allied Artists' Association

While in Paris in 1907,[12] Rutter had the idea for gaining greater exposure for progressive artists with the Allied Artists' Association (AAA), founded the following year and based on the model of the French Salon des Indépendants with the principle of non-juried shows of international artists, who could subscribe and choose which works they wished to enter (initially five pieces, later three). [5][6]

Rutter was a supporter of the Fitzroy Street Group, which had been founded in 1907, and succeeded in gaining the support of key members, Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, for the AAA. Rutter was a natural organiser and, with the help of Lucien Pissarro attracted 80 members.[19][12] Rutter was keen to mount a foreign section in the first show, and liaised over this with Jan de Holewinski (1871–1927), who was in London to arrange a Russian art and craft show.[5] The first AAA show in July 2008 was in the Royal Albert Hall and had over 3,000 works on display.[12]

In 1909, at the second show in the Royal Albert Hall, over 1,000 works were shown, mainly by British artists, but also the first works (two paintings and twelve woodcuts) exhibited in London by Wassily Kandinsky.[3] Rutter's friends in Leeds, Michael Sadler and his son, Michael Sadleir (who had modified the spelling of his surname) developed a relationship with Kandinsky, who assigned English translation rights for Concerning the Spiritual in Art to Sadleir.[3]