Kjersti Graver and Gunpowder artillery in the Middle Ages: Difference between pages

Geschichte (talk | contribs) husband |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

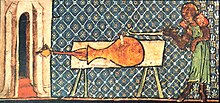

[[Image:EarlyCannonDeNobilitatibusSapientiiEtPrudentiisRegumManuscriptWalterdeMilemete1326.jpg|thumb|The earliest illustration of a European cannon, from around 1327.]] |

|||

'''Kjersti Graver''' (born 8 October 1945) is a Norwegian jurist. |

|||

'''[[Cannon]] in the Middle Ages''' were large tubular [[firearm]]s designed to fire a heavy [[projectile]] over a long distance. They were used in [[China]], [[Europe]] and the [[Middle East]] during the period, and became an important type of [[artillery]]. |

|||

Although [[gunpowder]] was known in Europe during the [[High Middle Ages]], it was not until the [[Late Middle Ages]] that cannon were widely developed. The first cannon in Europe were probably used in [[Iberian Peninsula|Iberia]], during the [[Islam]]ic wars against the [[Christian]]s in the 13th century; their use was also first documented in the Middle East around this time. [[English cannon]] first appeared in 1327, and later saw more general use during the [[Hundred Years' War]], when primitive cannon were engaged at the [[Battle of Crécy]] in 1346. By the end of the 14th century, the use of cannon was also recorded in [[Russia]], [[Byzantium]] and the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

|||

She was born in [[Oslo]]. She served as the [[Norwegian Consumer Ombudsman]] from 1987 to 1995, having previously worked as a sub-director from 1979 to 1984.<ref name="snl">{{cite encyclopedia |year=2007 |title =Bjarkøy, Torfinn |encyclopedia=Aschehoug og Gyldendals Store norske leksikon |publisher=Kunnskapsforlaget |location= |url=http://www.snl.no/article.html?id=469546 }}</ref> During this period she was behind a [[prohibition]] of the [[skateboard]] in Norway.<ref>{{cite news |first=Astrid |last=Meland |title=De forbød skateboard i Norge |url=http://www.dagbladet.no/magasinet/2008/01/24/524857.html |work=Dagbladet |language=Norwegian |date=25 January 2008 |accessdate=2008-09-12 }}</ref> In 1995 she was appointed as a [[presiding judge]] (''lagdommer'') in the [[Borgarting Court of Appeal]].<ref name="snl">b</ref> |

|||

The earliest medieval cannon, the ''[[pot-de-fer]]'', had bulbous, vase-like shape, and was used more for psychological effect than for causing physical damage. The later [[culverin]] was transitional between the [[handgun]] and the full cannon, and was used as an [[anti-personnel weapon]]. During the 15th century, cannon advanced significantly, so that [[Bombard (weapon)|bombards]] were effective [[siege engine]]s. Towards the end of the period, cannon gradually replaced [[siege engines]]—among other forms of aging weaponry—on the battlefield. |

|||

She is married to [[Lars Oftedal Broch]], grandson of [[Lars Oftedal]].<ref name="snl">{{cite encyclopedia |year=2007 |title=Broch, Lars Oftedal |encyclopedia=Aschehoug og Gyldendals Store norske leksikon |publisher=Kunnskapsforlaget |location= |url=http://www.snl.no/article.html?id=824135}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Middle English]] word ''Canon'' was derived from the [[Italian language|Old Italian]] word ''cannone'', meaning ''large tube'', which came from [[Latin]] ''canna'', meaning ''cane'' or ''reed''.<ref name="Definition and etymology of cannon">{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Cannon|title=Definition and etymology of "cannon"|publisher=[[Webster's Dictionary]]|accessdate=2008-06-02}}</ref> The Latinised word ''canon'' has been used for a gun since 1326 in Italy, and since 1418 in English. The word ''Bombardum'', or "bombard", was earliest term used for "cannon", but from 1430 it came to refer only to the largest weapons.<ref name="Nitrates">{{cite web |url=http://www.du.edu/~jcalvert/tech/cannon.htm |title=Cannons and Gunpowder |publisher=Mysite.du.edu/~jcalvert/index.htm |author=Calvert, Dr James B |accessdate=2008-06-02 |date=2007-07-08|}}</ref> |

|||

==Early use in China and East Asia== |

|||

{{Cannon}} |

|||

{{details|History of gunpowder}} |

|||

{{see also|Technology of Song Dynasty}} |

|||

==Use in the Islamic world== |

|||

{{see also|Inventions in the Islamic world|Alchemy and chemistry in Islam|Great Turkish Bombard}} |

|||

The Arabs acquired knowledge of gunpowder some time after 1240, but before 1280, by which time Hasan al-Rammah had written, in Arabic, recipes for gunpowder, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries.<ref>{{Citation | last = Kelly | first = Jack | title = Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World | publisher = Basic Books | year = 2004}}.</ref> |

|||

[[Ahmad Y. al-Hassan]] claims that the [[Battle of Ain Jalut]] in 1260 saw the [[Mamluk]]s use against the [[Mongols]] in "the first cannon in history" gunpowder formulae which were almost identical with the ideal composition for explosive gunpowder, which he claims were not known in China or Europe until much later.<ref name="Gunpowder Composition">{{cite web|publisher=[[Ahmad Y Hassan]]|last=Hassan|first=Ahmad Y|authorlink=Ahmad Y Hassan|url=http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%202.htm|title=Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries|accessdate=2008-06-08}}</ref><ref name=Hassan>{{cite web|last=Hassan|first=Ahmad Y|authorlink=Ahmad Y Hassan|url=http://www.history-science-technology.com/Articles/articles%2072.htm|title=Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries|accessdate=2007-02-17|publisher=[[Ahmad Y Hassan]]}}</ref> However, Iqtidar Alam Khan states that it was invading [[Mongols]] who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world<ref>{{Citation | last=Khan | first=Iqtidar Alam | title=Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols | journal=Journal of Asian History | volume=30 | year=1996 | pages=41–5}}.</ref> and cites [[Mamluk]] antagonism towards early riflemen in their infantry as an example of how gunpowder weapons were not always met with open acceptance in the Middle East.<ref name="khan 6">{{Citation | last =Khan | first =Iqtidar Alam | year =2004 | title =Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India | publisher =Oxford University Press}}.</ref> |

|||

Al-Hassan interprets [[Ibn Khaldun]] as reporting the use of cannon as [[siege machine]]s by the [[Marinid]] sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf at the siege of [[Sijilmasa]] in 1274.<ref name="Gunpowder Composition"/> Also intended for [[siege warfare]], the first [[supergun]], the [[Great Turkish Bombard]], was used by the troops of [[Mehmed II]] to [[Fall of Constantinople|capture]] [[Constantinople]], in 1453. Urban, a [[Hungary|Hungarian]] cannon engineer, is credited with the invention of this cannon.<ref name="The Medieval Siege">Bradbury, p 293</ref> It had a {{convert|762|mm|in|0|sing=on|abbr=on}} bore, and could fire {{convert|544|kg|abbr=on|sing=on}} stones a mile, and the sound of their blast could reportedly be heard from a distance of {{convert|10|mi|km|0}}.<ref name="The Medieval Siege"/> The Great Turkish Bombards were cast in bronze and made in two parts: the chase and the [[breech-loading weapon|breech]], which, together, weighed 16 [[tonne]]s.<ref>Gat, p 461</ref> The two parts were screwed together using levers to facilitate the work. |

|||

Another weapon invented in the [[Muslim world|Islamic world]], fashioned for killing infantry, was the first known [[autocannon]]. It was invented in the 16th century, by Fathullah Shirazi, a [[Persian people|Persian]]-[[History of India|Indian]] [[polymath]] and mechanical engineer, who worked for [[Akbar the Great]] in the [[Mughal Empire]]. As opposed to the [[polybolos]] and [[repeating crossbow]]s used earlier in [[Ancient Greece]] and China respectively, Shirazi's rapid-firing machine had multiple [[gun barrel]]s that fired from a hand cannon.<ref>Bag, p 431–436 </ref> |

|||

==Spread to Europe== |

|||

[[Image:Roger-bacon-statue.jpg|thumb|150px|[[Roger Bacon]] described the first gunpowder in [[Europe]].]] |

|||

In Europe, the first mention of gunpowder's composition in express terms appeared in [[Roger Bacon]]'s "''De nullitate magiæ''" at Oxford, published in 1216.<ref>{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia Britannica|year=1771|location=London|chapter=Gunpowder|quote = <!-- original uses Long s --> frier Bacon, our countryman, mentions the compoſition in expreſs terms, in his treatiſe ''De nullitate magiæ'', publiſhed at Oxford, in the year 1216.}}; Note the [[Long s]].</ref> Later, in 1248, his "''Opus Maior''" describes a recipe for gunpowder and recognized its military use: |

|||

{{long quotation|"We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances ... By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army ... In order to produce this artificial lightning and thunder it is necessary to take saltpeter, sulfur, and Luru Vopo Vir Can Utriet."<ref>Braun, p 28</ref>}} |

|||

<!-- This probably isn't needed here, maybe in Gunpowder article: When he wrote an abridged version of this work he mentions gunpowder in a different way: The text goes like this: {{long quotation|"As everyone knows, you can take 7 parts of saltpeter, 5 parts of hazelwood charcoal and 5 parts of sulfur and that makes thunder and lightning, provided you know the art".}} --> |

|||

In 1250, the [[Norway|Norwegian]] ''[[Konungs skuggsjá]]'' mentioned, in its military chapter, the use of "coal and sulphur" as the best weapon for [[naval warfare|ship-to-ship combat]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mediumaevum.com/75years/mirror/sec2.html#XXXVII |title=King's Mirror, Chapter XXXVII: The duties, activities and amusements of the Royal Guardsmen |publisher=Mediumaevum.com |accessdate=2008-07-20 |}}</ref> |

|||

===Muslim and Christian Iberia=== |

|||

The first confirmed use of gunpowder in Europe was the [[Moors|Moorish]] cannon, first used by the [[Al-Andalus|Andalusians]] in the [[Iberian Peninsula]], at the siege of [[Seville]] in 1248, and the siege of [[Niebla, Spain|Niebla]] in 1262.<ref name="Gunpowder Composition"/><ref name="Artillery Through the Ages">Manucy, p 3</ref> In reference to the siege to [[Alicante]] in 1331, the Spanish historian [[Jeronimo Zurita y Castro|Zurita]] recorded a "new machine that caused great terror. It threw iron balls with fire."<ref>Partington, p 191</ref><ref name="Gunpowder Composition"/> The Spanish historian [[Juan de Mariana]] recalled further use of cannon during the capture of [[Algeciras]] in 1342: |

|||

{{long quotation|"The besieged did great harm among the Christians with iron bullets they shot. This is the first time we find any mention of gunpowder and ball in our histories."<ref>Mariana</ref>}} |

|||

Juan de Mariana also relates that the English [[Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster|Earl of Derby]] and [[William Montacute, 1st Earl of Salisbury|Earl of Salisbury]] had both participated in the siege of Algeciras, and they could had conceivably transferred the knowledge about the effectiveness of cannon to England.<ref>Watson, p 331</ref> |

|||

The Iberian kings at the initial stages enlisted the help of [[Moors|Moorish]] experts: |

|||

{{long quotation|"The first artillery-masters on the Peninsula probably were Moors in Christian service. The king of [[Navarre]] had a Moor in his service in 1367 as ''maestro de las guarniciones de artilleria''. The Morisques of Tudela at that time had fame for their capacity in ''reparaciones de artilleria''."<ref>Hoffmeyer, p. 217.</ref>}} |

|||

===Britain and France=== |

|||

{{see also|English cannon|Pot-de-fer}} |

|||

[[Image:Vase cannonfortnelson.jpg|thumb|left|A reconstruction of the ''[[pot-de-fer]]'' vase cannon that fired arrows.]] |

|||

Cannon seem to have been introduced to the [[Kingdom of England]] in the 14th century, and is mentioned as being in use against the [[Kingdom of Scotland|Scots]] in 1327.<ref name="Bottomley24">Bottomley, p24</ref> The first metal cannon was the ''pot-de-fer'', first depicted in an illuminated [[manuscript]] by Walter de Milamete,<ref name="Carman">Carman, W.Y.</ref> of 1327 that was presented to [[Edward III]] upon his accession to the [[King of England|English throne]].<ref>Brodie, Fawn McKay; Brodie, Bernard</ref> The manuscript shows a four-legged stand supporting a "bulbous bottle", while the gunner stands well back, firing the charge with a red-hot iron bar.<ref name="Bottomley24"/> A bolt protrudes from the [[muzzle (firearm)|muzzle]], but no [[wadding|wad]] is shown.<ref name="Carman"/> Although illustrated in the treatise, no explanation or description was given.<ref name="Nossov">Nossov (2006), pp 205-208</ref> |

|||

This weapon, and others similar, were used by both the [[France in the Middle Ages|French]] and English during the [[Hundred Years' War]] (1337–1453), when cannon saw their first real use on the European battlefield.<ref name="Artillery Through the Ages"/> The cannon of the 14th century were still limited in many respects, as a modern historian summarises: |

|||

{{long quotation|"Early cannon were inferior in every respect to the great siege-engines: they were slow and small, they were limited… [in the 14th century] <!--Author uses abbreviation "C14"--> to firing bolts or 'garrots' and they had a very limited range. The weaknesses were due to limited technology: inability to forge or cast in one piece or make iron balls. They were probably as dangerous to their users as to the enemy and affected the morale of men (and horses) rather than damaged persons or buildings."<ref>Bottomley, p 24-25</ref>}} |

|||

During the 1340s, cannon were still relatively rare, and were only used in small numbers by a few states.<ref name="Nicolle">Nicolle, p 21</ref> "Ribaldis" were first mentioned in the English Privy Wardrobe accounts during preparations for the [[Battle of Crécy]] between 1345 and 1346.<ref name="Nicolle"/> These were believed to have shot large arrows and simple grapeshot, but they were so important they were directly controlled by the Royal Wardrobe.<ref name="Nicolle"/> According to the contemporary chronicler [[Jean Froissart]], the English cannon made "two or three discharges on the [[Genoese]]", which is taken to mean individual shots by two or three guns because of the time taken to reload such primitive artillery.<ref>Nicolle</ref> The Florentine [[Giovanni Villani]] agreed that they were destructive on the field, though he also indicated that the guns continued to fire upon French cavalry later in the battle: |

|||

{{long quotation|"The English guns cast iron balls by means of fire… They made a noise like thunder and caused much loss in men and horses… The Genoese were continually hit by the archers and the gunners… [by the end of the battle] the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls."<ref>Nicolle</ref>}} |

|||

==Advances in the Late Middle Ages== |

|||

<!--[[Image:HandBombardWesternEurope1380.jpg|thumb|right|European [[handgun]] of 1380]]--> |

|||

[[Image:SiegeOfOrleans1429.jpg|thumb|right|The first Western image of a battle with cannon: the [[Siege of Orleans]] in 1429]] |

|||

Similar cannon to those used at Crécy appeared also at the [[Siege of Calais]] in the same year, and by the 1380s the "ribaudekin" clearly became mounted on wheels.<ref name="Nicolle"/> Wheeled gun carriages became more commonplace by the end of the 15th century, and were more often cast in [[bronze]], rather than banding [[iron]] sections together.<ref name="Flodden">Sadler, p 22-23</ref> There were still the logistical problems both of transporting and of operating the cannon, and as many three dozen horses and oxen may have been required to move some of the great guns of the period.<ref name="Flodden"/> |

|||

Another small-bore cannon of the 14th century was the [[culverin]], whose name derives from the snake-like handles attached to it.<ref name="Bottomeley43"/> It was transitional between the [[handgun]] and the full cannon, and was used as an [[anti-personnel weapon]].<ref name="Bottomeley43">Bottomley, p 43</ref> The culverin was forged of iron and fixed to a wooden stock, and usually placed on a rest for firing.<ref name="Bennet91">Bennet, p 91</ref> Some of the [[loophole]]s in the [[gatehouse]] at [[Bodiam Castle]] appear to have been intended for culverin use.<ref name="Bottomeley43"/> |

|||

[[Image:Coulevriniers.jpg|thumb|left|150px|15th century culveriners.]] |

|||

The culverin was also common in 15th century battles, particularly among [[Duchy of Burgundy|Burgundian]] armies.<ref name="Bennet91"/> As the smallest of medieval gunpowder weapons, it was relatively light and portable.<ref name="Bennet91"/> It fired lead shot, which was inexpensive relative to other available materials.<ref name="Bennet91"/> There was also the [[demi-culverin]], which was smaller and had a bore of {{convert|4|in|cm}}.<ref name="Bottomeley43"/> |

|||

Considerable developments in the 15th century produced very effective "[[bombard]]s"<ref name="Bottomeley25">Bottomley, p 25</ref> — an early form of battering cannon used against walls and towers.<ref name="Bottomeley43"/><ref name="Bottomley17">Bottomley, p 17</ref> These were used both defensively and offensively. [[Bamburgh Castle]], previously thought impregnable, was taken by bombards in 1464.<ref name="Bottomeley25"/> The [[keep]] in Wark, Northumberland was described in 1517 as having five storeys "in each of which there were five great [[murder-holes]], shot with great vaults of stone, except one stage which is of timber, so that great bombards can be shot from each of them."<ref>Bottomley, p 16-17</ref> An example of a bombard was found in the [[moat]] of [[Bodiam Castle]], and a replica is now kept inside.<ref name="Bottomley17"/> |

|||

[[Image:HandCulverinWithSmallCannonsEurope15thCentury.jpg|thumb|right|Hand [[culverin]] (middle) with two small cannon, Europe, 15th century.]] |

|||

Artillery crews were generally recruited from the city craftsmen.<ref name="Miller18">Miller, p 18</ref> The master gunner was usually the same person as the caster.<ref name="Miller18"/> In larger contingents, the master gunners had responsibility for the heavier artillery pieces, and were accompanied by their journeymen as well as [[Smith (metalwork)|smith]]s, [[carpenter]]s, [[rope]] makers and [[carter]]s.<ref name="Miller18"/> Smaller field pieces would be manned by trained volunteers.<ref name="Miller18"/> At the [[Battle of Flodden Field]], each cannon had its crew of gunner, [[matross]]es and drivers, and a group of "[[Assault Pioneer|pioneers]]" were assigned to level to path ahead.<ref name="Flodden"/> Even with a level path, the gunpowder mixture used was unstable and could easily separate out into [[sulphur]], [[saltpetre]] and [[charcoal]] during transport.<ref name="Flodden"/> |

|||

Once on site, they would be fired at ground level behind a hinged timber shutter, to provide some protection to the artillery crew.<ref name="Flodden"/> Timber wedges were used to control the barrel's elevation.<ref name="Flodden"/> The majority of medieval cannon were breechloaders, although there was still no effort to standardise calibres.<ref name="Flodden"/> The usual loading equipment consisted of a copper loading scoop, a ramrod, and a felt brush or "sponge".<ref name="Miller18"/> A bucket of water was always kept beside the cannon.<ref name="Miller18"/> Skins or cloths soaked in cold water could be used to cool down the barrel, while acids could also be added to the water to clean out the inside of the barrel.<ref name="Miller18"/> Hot coals were used to heat the shot or keep the wire primer going.<ref name="Miller18"/> |

|||

Some Scottish kings were very interested in the development of cannon, including the unfortunate [[James II of Scotland|James II]], who was killed by the accidental explosion of one of his own cannon besieging [[Roxburgh Castle]] in 1460.<ref name="Sadler15">Sadler, p 15</ref> [[Mons Meg]], which dates from about the same time, is perhaps the most famous example of a Scottish cannon. [[James IV of Scotland|James IV]] was Scotland's first Renaissance figure, who also had a fascination with cannon, both at land and at sea.<ref name="Sadler15"/> By 1502, he was able to invest in a [[Scottish navy]], which was to have a large number of cannon — his flagship, the ''[[Great Michael]]'', was launched in 1511, with 36 great guns, 300 lesser pieces and 120 gunners.<ref name="Sadler15"/> |

|||

==Use in Eastern Europe== |

|||

[[Image:Tokhtamysh.jpg|thumb||right|''[[Siege of Moscow (1382)|Tokhtamysh's Invasion of Russia]]'', 1382. At this time, cannon and throwing-machines co-existed.]] |

|||

===Russia=== |

|||

The first cannon appeared in [[Kievan Rus'|Russia]] in the 1370-1380s, although initially their use was confined to sieges and the defence of fortresses.<ref name="Nossov52">Nossov (2007), p 52</ref> The first mention of cannon in Russian chronicles is of ''tyufyaks'', small [[howitzer]]-type cannon that fired [[case-shot]], used to defend [[Moscow]] against [[Tokhtamysh|Tokhtamysh Khan]] in 1382.<ref name="Nossov52"/> Cannon co-existed with throwing-machines until the mid-15th century, when they overtook the latter in terms of destructive power.<ref name="Nossov52"/> In 1446, a Russian city fell to cannon fire for the first time, although its wall was not destroyed.<ref name="Nossov52"/> The first stone wall to be destroyed in Russia by cannon fire came in 1481.<ref name="Nossov52"/> |

|||

===Byzantine and Ottoman Empires=== |

|||

During the 14th century, the [[Byzantine Empire]] began to accumulate its own cannon to face the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] threat, starting with medium-sized cannon {{convert|3|ft|m}} long and of 10" calibre.<ref name="Constantinople">Turnbull, p 39-41</ref> Only a few large bombards were under the Empire's control. The first definite use of artillery in the region was against the Ottoman siege of [[Constantinople]] in 1396, as the attackers did not yet have any gunpowder of their own. These loud Byzantine weapons, possibly operated by the Genoese or "[[Franks]]" of [[Galata]], forced the Turks to withdraw.<ref name="Constantinople"/> |

|||

The Ottomans had acquired their own cannon by the siege of 1422, using "[[Falconet (cannon)|falcons]]", which were short but wide cannon. The two sides were evenly matched technologically, and the Turks had to build barricades "in order to receive… the stones of the bombards."<ref name="Constantinople"/> Because the Empire at this time was facing economic problems, Pope [[Pius II]] promoted the affordable donation of cannon by European monarchs as a means of aid. Any new cannon after the 1422 siege were gifts from European states, and aside from these, no other advances were made to the Byzantine arsenal.<ref name="Constantinople"/> |

|||

[[Image:Great Turkish Bombard at Fort Nelson.JPG|thumb|left|A [[Great Turkish Bombard]], a heavy bronze [[muzzle-loading]] cannon, similar to those at the [[Fall of Constantinople|Siege of Constantinople]] in 1453]] |

|||

In contrast, when [[Sultan Mehmet II]] laid siege to Constantinople in April 1453, he used 68 Hungarian-made cannon, or [[Great Turkish Bombard]]s, the largest of which was {{convert|26|ft|m}} long and weighed 20 tons. This fired a 1,200 pound stone cannonball, and required an operating crew of 200 men.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.trivia-library.com/b/military-and-war-weapons-the-cannon.htm |title=Military and War Weapons: the Cannon |publisher=Trivia-library.com |accessdate=2008-07-20 |author=Wallechinsky, David |coauthors=Wallace, Irving |work=Reproduced from "The People's Almanac" series of books}}</ref> Two such bombards had initially been offered to the Byzantines by the Hungarian artillery expert Urban, which were the pinnacle of gunpowder technology at the time; he boasted that they could reduce "even the walls of Babylon".<ref name="Constantinople"/> However, the fact that the Byzantines could not afford it illustrates the financial costs of artillery at the time. These cannon also needed 70 oxen and 10,000 men just to transport them.<ref name="Constantinople"/> They were extremely loud, adding to their psychological impact, and Mehmet believed that those who unexpectedly heard it would be struck dumb.<ref name="Constantinople"/> |

|||

The 55 day bombardment of Constantinople left massive destruction, as recounted by the Greek chronicler Kritovoulos: |

|||

{{long quotation|"And the stone, borne with enormous force and velocity, hit the wall, which it immediately shook and knocked down and was itself broken into many fragments and scattered, hurling the pieces everywhere and killing those who happened to be nearby."<ref name="Constantinople"/>}} |

|||

Byzantine counter artillery allowed them to repel any visible Turkish weapons, and the defenders repulsed any attempts to storm any broken points in the walls and hastily repaired any damage. However, the walls could not be adapted for artillery, and towers were not good gun emplacements. There was even worry that the largest Byzantine cannon could cause more damage to their own walls than the Turkish cannon.<ref name="Constantinople"/> Gunpowder had also made the formerly devastating [[Greek fire]] obsolete, and with the final fall of what had once been the strongest walls in Europe on [[May 29]], "it was the end of an era in more ways than one".<ref name="Constantinople"/> |

|||

==Cannon at the end of the Middle Ages== |

|||

[[Image:Fortezza di Sarzana.jpg|thumb|right|The rounded walls of the 14th century [[Sarzana]] Castle showed adaption to gunpowder.]] |

|||

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, the development of cannon made revolutionary changes to siege warfare throughout Europe, with many [[castle]]s becoming susceptible to artillery fire. The primary aims in castle wall construction were height and thickness, but these became obsolete because they could be damaged by cannonballs.<ref name="Chartrand8">Chartrand, p 8</ref> Inevitably, many fortifications previously deemed impregnable proved inadequate in the face of gunpowder. The walls and towers of fortifications had to become lower and wider, and by the 1480s, "Italian tracing" had been developed, which used the corner [[bastion]] as the basis of fortifications for centuries to come.<ref name="Chartrand8"/> The introduction of artillery to siege warfare in the Middle Ages made geometry the main element of European military architecture.<ref name="Chartrand8"/> |

|||

In 16th century England, [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] began building [[Device Forts]] between 1539 and 1540 as artillery fortresses to counter the threat of invasion from France and Spain. They were built by the state at strategic points for the first powerful [[artillery battery|cannon batteries]], such as [[Deal Castle]], which was perfectly symmetrical, with a low, circular [[keep]] at its centre. Over 200 cannon and gun ports were set within the walls, and the fort was essentially a firing platform, with a shape that allowed many lines of fire; its low curved bastions were designed to deflect cannon balls.<ref name="Pockets">Wilkinson, ''Castles (Pocket Guides)''</ref> |

|||

To guard against artillery and gunfire, increasing use was made of earthen, brick and stone [[Breastwork (fortification)|breastworks]] and [[redoubt]]s, such as the geometric fortresses of the 17th century French [[Marquis de Vauban]]. Although the obsolescence of castles as fortifications was hastened by the developments of cannon from the 14th century on, many medieval castles still managed to "put up a prolonged resistance" against artillery during the [[English Civil War]] of 17th century.<ref>Bottomley, p 45</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Early thermal weapons]] |

|||

==Footnotes== |

|||

<references /> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia Britannica ''(1771)''|location=London}} |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

*{{cite journal|first=A. K.|last=Bag|year=2005|title=Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu|publisher=Indian Journal of History of Science|}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Bennet, Matthew |coauthors=Connolly, Peter |others=contributors John Gillingham and John Lazenby |title=The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare |publisher=Taylor & Francis |year=1998 |isbn=1579581161}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Bottomley, Frank|title=The Castle Explorer's Guide |publisher=Crown Publishers|location=|year=1983|isbn=0517421720}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Medieval Siege|last=Bradbury|first=Jim|year=1992|publisher=[[Boydell & Brewer]]|location=[[Rochester, New York]]|accessdate=2008-05-26| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xVCRpsfwkiUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Medieval+Siege&ei=uFHlR8GfL4a4zATBtaz6BA&sig=i4zssKy0j3v4ywdXXh-hFuQWkEo#PPA293,M1| isbn=0-85115-312-7}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Braun|first=Wernher Von|coauthors=Frederick Ira Ordway|title=History of Rocketry & Space Travel|publisher=[[Thomas Y. Crowell Co.]] |year=1967| isbn=9780690005882| isbn=0690005881}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Brodie, Fawn McKay; Brodie, Bernard |title=From Crossbow to H-Bomb |publisher=Indiana University Press |location=Bloomington |year=1973 |pages= |isbn=0-253-20161-6 |oclc= |doi=}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author= Carman, W.Y. |title=A History of Firearms: From Earliest Times to 1914 |publisher=Dover Publications |location=New York |year= |pages= |isbn=0-486-43390-0 |oclc= |doi=}} |

|||

*{{Cite book | last = Chartrand | first = René | title = French Fortresses in North America 1535–1763: Quebec, Montreal, Louisbourg and New Orleans | url = | publisher = [[Osprey Publishing]] | date = 2005-03-20 | isbn = 9781841767147 | }} |

|||

*{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=y4aXo_125REC&pg=PA461&lpg=PA461&dq=dardanelles+gun&source=web&ots=clIsmn271c&sig=RqX4Rhc1k57oZZVSWDi-H0ft9CA&hl=en#PPA461,M1|title=War in Human Civilization|year=2006|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|location=[[New York City]]|last=Gat|first=Azar|isbn=0-19-926213-6}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Arms and Armour in Spain|last=Hoffmeyer|first=Ada Bruhn de|isbn=0435–029x|publisher=Instituto do Estudios sobre Armas Antiguas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Patronato Menendez y Pelayo|year=1972|location=[[Madrid]]}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author= Gernet, Jacques | title=A History of Chinese Civilisation | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1996 | id=ISBN 0-521-49781-7}} |

|||

*{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=yYupSOK0BgIC&printsec=frontcover#PPA3,M1|title=Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America|last=Manucy|first=Albert|isbn=0788107453|publisher=Diane publishing|year=1994|accessdate=2008-05-26|}} |

|||

*Mariana, Juan de. ''Historia general de Espana'', 2 volumes, Madrid, 1608, ii, 27; English translation by Captain John Stephens, ''The General History of Spain'', 2 parts, London, 1699, p 2 64 |

|||

*{{Cite book | first = Douglas | last = Miller| title = The Swiss at War 1300-1500 | others= Illustrated by Gerry Embleton | publisher = [[Osprey Publishing]] | year = 1979 | isbn = 0-85045-334-8 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=mzkv1CYvkIYC&printsec=frontcover}} |

|||

*Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. |

|||

*{{Cite book | first = David | last = Nicolle| authorlink = David Nicolle | title = Crécy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow | publisher = [[Osprey Publishing]] | year = 2000 | isbn = 9781855329669 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=lujfZqpd2JoC&printsec=frontcover}} |

|||

*Nossov, Konstantin; ''Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons'', UK: Spellmount Ltd, 2006. ISBN 186227343X |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Nossov|first=Konstantin|year=2007|title=Medieval Russian Fortresses AD 862–1480|publisher=[[Osprey Publishing]]|isbn=9781846030932}} |

|||

*Partington, J. R., A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, reprint by Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 191 (Latin text of Zurita) |

|||

*{{Cite book | first = John | last = Sadler | authorlink = John Sadler (historian) | title = Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat |url = http://books.google.com/books?id=ZXX1SrxKTg0C&printsec=frontcover | publisher = [[Osprey Publishing]] | year = 2006 | isbn=9781841769592}} |

|||

*{{Cite book | first = Stephen | last = Turnbull | authorlink = Stephen Turnbull (historian) | title = The Walls of Constantinople AD 413–1453 | publisher = [[Osprey Publishing]] | year = 2004 | isbn = 1-84176-759-X | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=sVnXSObRUYIC&printsec=frontcover}} |

|||

*Watson, R. ''Chemical Essays'', vol. I, London, 1787, 1999. |

|||

*{{Cite book | last = Wilkinson | first = Philip | title = Pockets: Castles | publisher = [[Dorling Kindersley]] | date = [[1997-09-09]] | isbn = 0789420473 | isbn = 978-0789420473}} |

|||

{{start box}} |

|||

{{succession box |title=[[Norwegian Consumer Ombudsman]] |before=[[Hans Petter Lundgaard]] |after=[[Torfinn Bjarkøy]] |years=1987–1995}} |

|||

{{end box}} |

|||

[[Category:Cannon]] |

|||

{{BD|1945||Graver, Kjersti}} |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Medieval weapons]] |

||

[[Category:Norwegian judges]] |

|||

[[es:El cañón en la Edad Media]] |

|||

{{Norway-bio-stub}} |

|||

Revision as of 22:43, 12 October 2008

Cannon in the Middle Ages were large tubular firearms designed to fire a heavy projectile over a long distance. They were used in China, Europe and the Middle East during the period, and became an important type of artillery.

Although gunpowder was known in Europe during the High Middle Ages, it was not until the Late Middle Ages that cannon were widely developed. The first cannon in Europe were probably used in Iberia, during the Islamic wars against the Christians in the 13th century; their use was also first documented in the Middle East around this time. English cannon first appeared in 1327, and later saw more general use during the Hundred Years' War, when primitive cannon were engaged at the Battle of Crécy in 1346. By the end of the 14th century, the use of cannon was also recorded in Russia, Byzantium and the Ottoman Empire.

The earliest medieval cannon, the pot-de-fer, had bulbous, vase-like shape, and was used more for psychological effect than for causing physical damage. The later culverin was transitional between the handgun and the full cannon, and was used as an anti-personnel weapon. During the 15th century, cannon advanced significantly, so that bombards were effective siege engines. Towards the end of the period, cannon gradually replaced siege engines—among other forms of aging weaponry—on the battlefield.

The Middle English word Canon was derived from the Old Italian word cannone, meaning large tube, which came from Latin canna, meaning cane or reed.[1] The Latinised word canon has been used for a gun since 1326 in Italy, and since 1418 in English. The word Bombardum, or "bombard", was earliest term used for "cannon", but from 1430 it came to refer only to the largest weapons.[2]

Early use in China and East Asia

| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

|

Use in the Islamic world

The Arabs acquired knowledge of gunpowder some time after 1240, but before 1280, by which time Hasan al-Rammah had written, in Arabic, recipes for gunpowder, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries.[3]

Ahmad Y. al-Hassan claims that the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 saw the Mamluks use against the Mongols in "the first cannon in history" gunpowder formulae which were almost identical with the ideal composition for explosive gunpowder, which he claims were not known in China or Europe until much later.[4][5] However, Iqtidar Alam Khan states that it was invading Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world[6] and cites Mamluk antagonism towards early riflemen in their infantry as an example of how gunpowder weapons were not always met with open acceptance in the Middle East.[7]

Al-Hassan interprets Ibn Khaldun as reporting the use of cannon as siege machines by the Marinid sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf at the siege of Sijilmasa in 1274.[4] Also intended for siege warfare, the first supergun, the Great Turkish Bombard, was used by the troops of Mehmed II to capture Constantinople, in 1453. Urban, a Hungarian cannon engineer, is credited with the invention of this cannon.[8] It had a 762 mm (30 in) bore, and could fire 544 kg (1,199 lb) stones a mile, and the sound of their blast could reportedly be heard from a distance of 10 miles (16 km).[8] The Great Turkish Bombards were cast in bronze and made in two parts: the chase and the breech, which, together, weighed 16 tonnes.[9] The two parts were screwed together using levers to facilitate the work.

Another weapon invented in the Islamic world, fashioned for killing infantry, was the first known autocannon. It was invented in the 16th century, by Fathullah Shirazi, a Persian-Indian polymath and mechanical engineer, who worked for Akbar the Great in the Mughal Empire. As opposed to the polybolos and repeating crossbows used earlier in Ancient Greece and China respectively, Shirazi's rapid-firing machine had multiple gun barrels that fired from a hand cannon.[10]

Spread to Europe

In Europe, the first mention of gunpowder's composition in express terms appeared in Roger Bacon's "De nullitate magiæ" at Oxford, published in 1216.[11] Later, in 1248, his "Opus Maior" describes a recipe for gunpowder and recognized its military use:

"We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances ... By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army ... In order to produce this artificial lightning and thunder it is necessary to take saltpeter, sulfur, and Luru Vopo Vir Can Utriet."[12]

In 1250, the Norwegian Konungs skuggsjá mentioned, in its military chapter, the use of "coal and sulphur" as the best weapon for ship-to-ship combat.[13]

Muslim and Christian Iberia

The first confirmed use of gunpowder in Europe was the Moorish cannon, first used by the Andalusians in the Iberian Peninsula, at the siege of Seville in 1248, and the siege of Niebla in 1262.[4][14] In reference to the siege to Alicante in 1331, the Spanish historian Zurita recorded a "new machine that caused great terror. It threw iron balls with fire."[15][4] The Spanish historian Juan de Mariana recalled further use of cannon during the capture of Algeciras in 1342:

"The besieged did great harm among the Christians with iron bullets they shot. This is the first time we find any mention of gunpowder and ball in our histories."[16]

Juan de Mariana also relates that the English Earl of Derby and Earl of Salisbury had both participated in the siege of Algeciras, and they could had conceivably transferred the knowledge about the effectiveness of cannon to England.[17]

The Iberian kings at the initial stages enlisted the help of Moorish experts:

"The first artillery-masters on the Peninsula probably were Moors in Christian service. The king of Navarre had a Moor in his service in 1367 as maestro de las guarniciones de artilleria. The Morisques of Tudela at that time had fame for their capacity in reparaciones de artilleria."[18]

Britain and France

Cannon seem to have been introduced to the Kingdom of England in the 14th century, and is mentioned as being in use against the Scots in 1327.[19] The first metal cannon was the pot-de-fer, first depicted in an illuminated manuscript by Walter de Milamete,[20] of 1327 that was presented to Edward III upon his accession to the English throne.[21] The manuscript shows a four-legged stand supporting a "bulbous bottle", while the gunner stands well back, firing the charge with a red-hot iron bar.[19] A bolt protrudes from the muzzle, but no wad is shown.[20] Although illustrated in the treatise, no explanation or description was given.[22]

This weapon, and others similar, were used by both the French and English during the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), when cannon saw their first real use on the European battlefield.[14] The cannon of the 14th century were still limited in many respects, as a modern historian summarises:

"Early cannon were inferior in every respect to the great siege-engines: they were slow and small, they were limited… [in the 14th century] to firing bolts or 'garrots' and they had a very limited range. The weaknesses were due to limited technology: inability to forge or cast in one piece or make iron balls. They were probably as dangerous to their users as to the enemy and affected the morale of men (and horses) rather than damaged persons or buildings."[23]

During the 1340s, cannon were still relatively rare, and were only used in small numbers by a few states.[24] "Ribaldis" were first mentioned in the English Privy Wardrobe accounts during preparations for the Battle of Crécy between 1345 and 1346.[24] These were believed to have shot large arrows and simple grapeshot, but they were so important they were directly controlled by the Royal Wardrobe.[24] According to the contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart, the English cannon made "two or three discharges on the Genoese", which is taken to mean individual shots by two or three guns because of the time taken to reload such primitive artillery.[25] The Florentine Giovanni Villani agreed that they were destructive on the field, though he also indicated that the guns continued to fire upon French cavalry later in the battle:

"The English guns cast iron balls by means of fire… They made a noise like thunder and caused much loss in men and horses… The Genoese were continually hit by the archers and the gunners… [by the end of the battle] the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls."[26]

Advances in the Late Middle Ages

Similar cannon to those used at Crécy appeared also at the Siege of Calais in the same year, and by the 1380s the "ribaudekin" clearly became mounted on wheels.[24] Wheeled gun carriages became more commonplace by the end of the 15th century, and were more often cast in bronze, rather than banding iron sections together.[27] There were still the logistical problems both of transporting and of operating the cannon, and as many three dozen horses and oxen may have been required to move some of the great guns of the period.[27]

Another small-bore cannon of the 14th century was the culverin, whose name derives from the snake-like handles attached to it.[28] It was transitional between the handgun and the full cannon, and was used as an anti-personnel weapon.[28] The culverin was forged of iron and fixed to a wooden stock, and usually placed on a rest for firing.[29] Some of the loopholes in the gatehouse at Bodiam Castle appear to have been intended for culverin use.[28]

The culverin was also common in 15th century battles, particularly among Burgundian armies.[29] As the smallest of medieval gunpowder weapons, it was relatively light and portable.[29] It fired lead shot, which was inexpensive relative to other available materials.[29] There was also the demi-culverin, which was smaller and had a bore of 4 inches (10 cm).[28]

Considerable developments in the 15th century produced very effective "bombards"[30] — an early form of battering cannon used against walls and towers.[28][31] These were used both defensively and offensively. Bamburgh Castle, previously thought impregnable, was taken by bombards in 1464.[30] The keep in Wark, Northumberland was described in 1517 as having five storeys "in each of which there were five great murder-holes, shot with great vaults of stone, except one stage which is of timber, so that great bombards can be shot from each of them."[32] An example of a bombard was found in the moat of Bodiam Castle, and a replica is now kept inside.[31]

Artillery crews were generally recruited from the city craftsmen.[33] The master gunner was usually the same person as the caster.[33] In larger contingents, the master gunners had responsibility for the heavier artillery pieces, and were accompanied by their journeymen as well as smiths, carpenters, rope makers and carters.[33] Smaller field pieces would be manned by trained volunteers.[33] At the Battle of Flodden Field, each cannon had its crew of gunner, matrosses and drivers, and a group of "pioneers" were assigned to level to path ahead.[27] Even with a level path, the gunpowder mixture used was unstable and could easily separate out into sulphur, saltpetre and charcoal during transport.[27]

Once on site, they would be fired at ground level behind a hinged timber shutter, to provide some protection to the artillery crew.[27] Timber wedges were used to control the barrel's elevation.[27] The majority of medieval cannon were breechloaders, although there was still no effort to standardise calibres.[27] The usual loading equipment consisted of a copper loading scoop, a ramrod, and a felt brush or "sponge".[33] A bucket of water was always kept beside the cannon.[33] Skins or cloths soaked in cold water could be used to cool down the barrel, while acids could also be added to the water to clean out the inside of the barrel.[33] Hot coals were used to heat the shot or keep the wire primer going.[33]

Some Scottish kings were very interested in the development of cannon, including the unfortunate James II, who was killed by the accidental explosion of one of his own cannon besieging Roxburgh Castle in 1460.[34] Mons Meg, which dates from about the same time, is perhaps the most famous example of a Scottish cannon. James IV was Scotland's first Renaissance figure, who also had a fascination with cannon, both at land and at sea.[34] By 1502, he was able to invest in a Scottish navy, which was to have a large number of cannon — his flagship, the Great Michael, was launched in 1511, with 36 great guns, 300 lesser pieces and 120 gunners.[34]

Use in Eastern Europe

Russia

The first cannon appeared in Russia in the 1370-1380s, although initially their use was confined to sieges and the defence of fortresses.[35] The first mention of cannon in Russian chronicles is of tyufyaks, small howitzer-type cannon that fired case-shot, used to defend Moscow against Tokhtamysh Khan in 1382.[35] Cannon co-existed with throwing-machines until the mid-15th century, when they overtook the latter in terms of destructive power.[35] In 1446, a Russian city fell to cannon fire for the first time, although its wall was not destroyed.[35] The first stone wall to be destroyed in Russia by cannon fire came in 1481.[35]

Byzantine and Ottoman Empires

During the 14th century, the Byzantine Empire began to accumulate its own cannon to face the Ottoman threat, starting with medium-sized cannon 3 feet (0.91 m) long and of 10" calibre.[36] Only a few large bombards were under the Empire's control. The first definite use of artillery in the region was against the Ottoman siege of Constantinople in 1396, as the attackers did not yet have any gunpowder of their own. These loud Byzantine weapons, possibly operated by the Genoese or "Franks" of Galata, forced the Turks to withdraw.[36]

The Ottomans had acquired their own cannon by the siege of 1422, using "falcons", which were short but wide cannon. The two sides were evenly matched technologically, and the Turks had to build barricades "in order to receive… the stones of the bombards."[36] Because the Empire at this time was facing economic problems, Pope Pius II promoted the affordable donation of cannon by European monarchs as a means of aid. Any new cannon after the 1422 siege were gifts from European states, and aside from these, no other advances were made to the Byzantine arsenal.[36]

In contrast, when Sultan Mehmet II laid siege to Constantinople in April 1453, he used 68 Hungarian-made cannon, or Great Turkish Bombards, the largest of which was 26 feet (7.9 m) long and weighed 20 tons. This fired a 1,200 pound stone cannonball, and required an operating crew of 200 men.[37] Two such bombards had initially been offered to the Byzantines by the Hungarian artillery expert Urban, which were the pinnacle of gunpowder technology at the time; he boasted that they could reduce "even the walls of Babylon".[36] However, the fact that the Byzantines could not afford it illustrates the financial costs of artillery at the time. These cannon also needed 70 oxen and 10,000 men just to transport them.[36] They were extremely loud, adding to their psychological impact, and Mehmet believed that those who unexpectedly heard it would be struck dumb.[36]

The 55 day bombardment of Constantinople left massive destruction, as recounted by the Greek chronicler Kritovoulos:

"And the stone, borne with enormous force and velocity, hit the wall, which it immediately shook and knocked down and was itself broken into many fragments and scattered, hurling the pieces everywhere and killing those who happened to be nearby."[36]

Byzantine counter artillery allowed them to repel any visible Turkish weapons, and the defenders repulsed any attempts to storm any broken points in the walls and hastily repaired any damage. However, the walls could not be adapted for artillery, and towers were not good gun emplacements. There was even worry that the largest Byzantine cannon could cause more damage to their own walls than the Turkish cannon.[36] Gunpowder had also made the formerly devastating Greek fire obsolete, and with the final fall of what had once been the strongest walls in Europe on May 29, "it was the end of an era in more ways than one".[36]

Cannon at the end of the Middle Ages

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, the development of cannon made revolutionary changes to siege warfare throughout Europe, with many castles becoming susceptible to artillery fire. The primary aims in castle wall construction were height and thickness, but these became obsolete because they could be damaged by cannonballs.[38] Inevitably, many fortifications previously deemed impregnable proved inadequate in the face of gunpowder. The walls and towers of fortifications had to become lower and wider, and by the 1480s, "Italian tracing" had been developed, which used the corner bastion as the basis of fortifications for centuries to come.[38] The introduction of artillery to siege warfare in the Middle Ages made geometry the main element of European military architecture.[38]

In 16th century England, Henry VIII began building Device Forts between 1539 and 1540 as artillery fortresses to counter the threat of invasion from France and Spain. They were built by the state at strategic points for the first powerful cannon batteries, such as Deal Castle, which was perfectly symmetrical, with a low, circular keep at its centre. Over 200 cannon and gun ports were set within the walls, and the fort was essentially a firing platform, with a shape that allowed many lines of fire; its low curved bastions were designed to deflect cannon balls.[39]

To guard against artillery and gunfire, increasing use was made of earthen, brick and stone breastworks and redoubts, such as the geometric fortresses of the 17th century French Marquis de Vauban. Although the obsolescence of castles as fortifications was hastened by the developments of cannon from the 14th century on, many medieval castles still managed to "put up a prolonged resistance" against artillery during the English Civil War of 17th century.[40]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Definition and etymology of "cannon"". Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Calvert, Dr James B (2007-07-08). "Cannons and Gunpowder". Mysite.du.edu/~jcalvert/index.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books.

- ^ a b c d Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". Ahmad Y Hassan. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ^ Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries". Ahmad Y Hassan. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Bradbury, p 293

- ^ Gat, p 461

- ^ Bag, p 431–436

- ^ "Gunpowder". Encyclopedia Britannica. London. 1771.

frier Bacon, our countryman, mentions the compoſition in expreſs terms, in his treatiſe De nullitate magiæ, publiſhed at Oxford, in the year 1216.

; Note the Long s. - ^ Braun, p 28

- ^ "King's Mirror, Chapter XXXVII: The duties, activities and amusements of the Royal Guardsmen". Mediumaevum.com. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Manucy, p 3

- ^ Partington, p 191

- ^ Mariana

- ^ Watson, p 331

- ^ Hoffmeyer, p. 217.

- ^ a b Bottomley, p24

- ^ a b Carman, W.Y.

- ^ Brodie, Fawn McKay; Brodie, Bernard

- ^ Nossov (2006), pp 205-208

- ^ Bottomley, p 24-25

- ^ a b c d Nicolle, p 21

- ^ Nicolle

- ^ Nicolle

- ^ a b c d e f g Sadler, p 22-23

- ^ a b c d e Bottomley, p 43

- ^ a b c d Bennet, p 91

- ^ a b Bottomley, p 25

- ^ a b Bottomley, p 17

- ^ Bottomley, p 16-17

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller, p 18

- ^ a b c Sadler, p 15

- ^ a b c d e Nossov (2007), p 52

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Turnbull, p 39-41

- ^ Wallechinsky, David. "Military and War Weapons: the Cannon". Reproduced from "The People's Almanac" series of books. Trivia-library.com. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Chartrand, p 8

- ^ Wilkinson, Castles (Pocket Guides)

- ^ Bottomley, p 45

References

- Encyclopedia Britannica (1771). London.

- Bag, A. K. (2005). "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu". Indian Journal of History of Science.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Bennet, Matthew (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. contributors John Gillingham and John Lazenby. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1579581161.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Bottomley, Frank (1983). The Castle Explorer's Guide. Crown Publishers. ISBN 0517421720.

- Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. Rochester, New York: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-85115-312-7. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- Braun, Wernher Von (1967). History of Rocketry & Space Travel. Thomas Y. Crowell Co. ISBN 0690005881.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Brodie, Fawn McKay; Brodie, Bernard (1973). From Crossbow to H-Bomb. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20161-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Carman, W.Y. A History of Firearms: From Earliest Times to 1914. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43390-0.

- Chartrand, René (2005-03-20). French Fortresses in North America 1535–1763: Quebec, Montreal, Louisbourg and New Orleans. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781841767147.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Gat, Azar (2006). War in Human Civilization. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926213-6.

- Hoffmeyer, Ada Bruhn de (1972). Arms and Armour in Spain. Madrid: Instituto do Estudios sobre Armas Antiguas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Patronato Menendez y Pelayo. ISBN 0435–029x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49781-7.

- Manucy, Albert (1994). Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America. Diane publishing. ISBN 0788107453. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

- Mariana, Juan de. Historia general de Espana, 2 volumes, Madrid, 1608, ii, 27; English translation by Captain John Stephens, The General History of Spain, 2 parts, London, 1699, p 2 64

- Miller, Douglas (1979). The Swiss at War 1300-1500. Illustrated by Gerry Embleton. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-334-8.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Nossov, Konstantin; Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons, UK: Spellmount Ltd, 2006. ISBN 186227343X

- Nossov, Konstantin (2007). Medieval Russian Fortresses AD 862–1480. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781846030932.

- Partington, J. R., A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, reprint by Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 191 (Latin text of Zurita)

- Sadler, John (2006). Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781841769592.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2004). The Walls of Constantinople AD 413–1453. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-759-X.

- Watson, R. Chemical Essays, vol. I, London, 1787, 1999.

- Wilkinson, Philip (1997-09-09). Pockets: Castles. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0789420473.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)