Indus Valley Civilisation

Template:South Asian history The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1700 BCE, flourished 2600–1900 BCE), abbreviated IVC, was an ancient civilization that flourished in the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra river valleys primarily in what is now Pakistan and western India, parts of Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. Another name for this civilization is the Harappan Civilization, after the first of its cities to be excavated, Harappa. Although the IVC might have been known to the Sumerians as Meluhha, the modern world discovered it only in the 1920s as a result of archaeological excavations.

The IVC is a likely candidate for a Proto-Dravidian culture.[1] Alternatively, Proto-Munda, Proto-Indo-Iranian or a "lost phylum" are sometimes suggested for the language of the IVC (see Substratum in Vedic Sanskrit).[2]

The civilization is sometimes referred to as the Indus Ghaggar-Hakra civilization[3] or the Indus-Saraswati civilization. The appellation Indus-Saraswati is based on the possible identification of the Ghaggar-Hakra River with the ancient Saraswati river of the Rig Veda,[4] but this usage is disputed.[5]

Discovery and excavation

The ruins of Harappa were first described in 1842 by Charles Masson in his Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, where locals talked of an ancient city extending "thirteen cosses" (about 25 miles), but no archaeological interest would attach to this for nearly a century.[6]

In 1856, British engineers John and William Brunton were laying the East Indian Railway Company line connecting Karachi and Lahore. John wrote: "[I] was much exercised in my mind how we were to get ballast for the line of the railway." They were told of an ancient ruined city near the lines, called Brahminabad. Visiting the city, he found it full of hard well-burnt bricks; and "convinced that there was a grand quarry for the ballast I wanted", the city of Brahminabad was reduced to ballast.[7]. A few months later, further north, John's brother William Brunton's "section of the line ran near another ruined city, bricks from which had already been used by villagers in the nearby village of Harappa at the same site. These bricks now provided ballast along 93 miles of the railroad track running from Karachi to Lahore." [7]

It was more than half a century later, in 1912, that Harappan seals—with the then unknown symbols—were discovered by J. Fleet, prompting an excavation campaign under Sir John Hubert Marshall in 1921/22, and resulting in the discovery of the hitherto unknown civilization at Harappa by Sir John Marshall, Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni and Madho Sarup Vats, and at Mohenjo-daro by Rakhal Das Banerjee, E. J. H. MacKay, and Sir John Marshall. By 1931, much of Mohenjo-Daro had been excavated, but excavations continued, such as that led by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, director of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1944. Among other archaeologists who worked on IVC sites before the partition of the subcontinent in 1947 were Ahmad Hasan Dani, Brij Basi Lal, Nani Gopal Majumdar, and Sir Aurel Stein.

Following the partition of British India, the area of the IVC was divided between Pakistan and the India and excavations from this time include those led by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in 1949, archaeological adviser to the Government of Pakistan. Outposts of the Indus Valley civilization were excavated as far west as Sutkagan Dor in Baluchistan, as far north as the Oxus river in Afghanistan.

Periodisation

The mature phase of the Harappan civilization lasted from c. 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. With the inclusion of the predecessor and successor cultures—Early Harappan and Late Harappan, respectively—the entire Indus Valley Civilization may be taken to have lasted from the 33rd to the 14th centuries BCE. Two terms are employed for the periodization of the IVC: Phases and Eras.[8][9] The Early Harappan, Mature Harappan, and Late Harappan phases are also called the "Regionalisation," "Integration," and "Localisation" eras, respectively, with the Regionalization era reaching back to the Neolithic Mehrgarh II period. "Discoveries at Mehrgarh changed the entire concept of the Indus civilization," according to Ahmad Hasan Dani, professor emeritus at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, "There we have the whole sequence, right from the beginning of settled village life."[10]

| Date range | Phase | Era |

| 5500-3300 | Mehrgarh II-VI (Pottery Neolithic) | Regionalisation Era |

|---|---|---|

| 3300-2600 | Early Harappan (Early Bronze Age) | |

| 3300-2800 | Harappan 1 (Ravi Phase) | |

| 2800-2600 | Harappan 2 (Kot Diji Phase, Nausharo I, Mehrgarh VII) | |

| 2600-1900 | Mature Harappan (Middle Bronze Age) | Integration Era |

| 2600-2450 | Harappan 3A (Nausharo II) | |

| 2450-2200 | Harappan 3B | |

| 2200-1900 | Harappan 3C | |

| 1900-1300 | Late Harappan (Cemetery H, Late Bronze Age) | Localisation Era |

| 1900-1700 | Harappan 4 | |

| 1700-1300 | Harappan 5 |

Geography

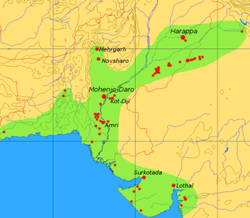

The Indus Valley Civilization extended from Balochistan to Gujarat, with an upward reach to Punjab from east of the river Jhelum to Rupar on the upper Sutlej; Recently, Indus sites have been discovered in Pakistan's NW Frontier Province as well. Coastal settlements extended from Sutkagan Dor[11] in Western Baluchistan to Lothal[12] in Gujarat. The Indus Valley Civilization encompassed most of Pakistan as well as the western states of India. An Indus Valley site has been found on the Oxus river at Shortughai in northern Afghanistan,[13] in the Gomal river valley in north-west Pakistan,[14] at Manda on the Beas River near Jammu,[15] India, and at Alamgirpur on the Hindon River, only 28 km from Delhi.[16] Indus Valley sites have been found most often on rivers, but also on the ancient sea-coast,[17] for example Balakot,[18] and on islands, for example, Dholavira.[19]

There is evidence of dry river beds overlapping with the Hakra channel in Pakistan and the seasonal Ghaggar River in India. Many Indus Valley (or Harappan) sites have been discovered along the Ghaggar-Hakra beds.[20] Among them are: Rupar, Rakhigarhi, Sothi, Kalibangan, and Ganwariwala.[21] According to J. G. Shaffer and D. A. Lichtenstein[22] the Harappan Civilization "is a fusion of the Bagor, Hakra, and Koti Dij traditions or 'ethnic groups' in the Ghaggar-Hakra valley on the borders of India and Pakistan."[20]

According to some archaeologists over 500 Harappan sites have been discovered along the dried up river beds of the Ghaggar-Hakra River and its tributaries,[23] in contrast to only about 100 along the Indus and its tributaries,[24] consequently, in their opinion, the appellation Indus Ghaggar-Hakra civilisation or Indus-Saraswati civilisation is justified. However, these arguments are disputed by other archaeologists who state that the Ghaggar-Hakra desert area has been left untouched by settlements and agriculture since the end of the Indus period and hence shows more sites than found in the alluvium of the Indus valley; second, that the number of Harappan sites along the Ghaggar-Hakra river beds have been exaggerated and that the Ghaggar-Hakra, when it existed, was a tributary of the Indus, so the new nomenclature is redundant.[25]

Early Harappan

The Early Harappan Ravi Phase, named after the nearby Ravi River, lasted from circa 3300 BCE until 2800 BCE. It is related to the Hakra Phase, identified in the Ghaggar-Hakra River Valley to the west, and predates the Kot Diji Phase (2800-2600 BCE, Harappan 2), named after a site in northern Sindh, Pakistan, near Mohenjo Daro. The earliest examples of the "Indus script" date from around 3000 BCE.[2]

The mature phase of earlier village cultures is represented by Rehman Dheri and Amri in Pakistan.[26] Kot Diji (Harappan 2) represents the phase leading up to Mature Harappan, with the citadel representing centralised authority and an increasingly urban quality of life. Another town of this stage was found at Kalibangan in India on the Hakra River.[27]

Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. Villagers had, by this time, domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates and cotton, as well as various animals, including the water buffalo.

Mature Harappan

By 2600 BCE, the Early Harappan communities had been turned into large urban centers. Such urban centers include Harappa and Mohenjo Daro in Pakistan and Lothal in India. In total, over 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Ghaggar and Indus Rivers and their tributaries.

By 2500 BCE, irrigation had transformed the region. [citation needed]

Cities

A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture is evident in the Indus Valley Civilization. The quality of municipal town planning suggests knowledge of urban planning and efficient municipal governments which placed a high priority on hygiene. The streets of major cities such as Mohenjo-daro or Harappa were laid out in perfect grid patterns. The houses were protected from noise, odors, and thieves.[citation needed]

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and the recently discovered Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's first urban sanitation systems. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. The house-building in some villages in the region still resembles in some respects the house-building of the Harappans.[28]

The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage that were developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region, were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than those in some areas of Pakistan and India today. The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms and protective walls. The massive citadels of Indus cities, that protected the Harappans from floods and attackers, were larger than most Mesopotamian ziggurats.[citation needed]

The purpose of the citadel remains debated. In sharp contrast to this civilization's contemporaries, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built. There is no conclusive evidence of palaces or temples - or of kings, armies, or priests. Some structures are thought to have been granaries. Found at one city is an enormous well-built bath, which may have been a public bath. Although the citadels were walled, it is far from clear that these structures were defensive. They may have been built to divert flood waters.

Most city dwellers appear to have been traders or artisans, who lived with others pursuing the same occupation in well-defined neighborhoods. Materials from distant regions were used in the cities for constructing seals, beads and other objects. Among the artifacts discovered were beautiful beads of glazed stone called faïence. The seals have images of animals, gods and other types of inscriptions. Some of the seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods and most probably had other uses.

Although some houses were larger than others, Indus Civilization cities were remarkable for their apparent egalitarianism. All the houses had access to water and drainage facilities. This gives the impression of a society with low wealth concentration.

Science

The people of the Indus Civilization achieved great accuracy in measuring length, mass and time. They were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures. Their measurements were extremely precise. Their smallest division, which is marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal, was approximately 1.704 mm, the smallest division ever recorded on a scale of the Bronze Age. Harappan engineers followed the decimal division of measurement for all practical purposes, including the measurement of mass as revealed by their hexahedron weights.

These brick weights were in a perfect ratio of 4:2:1 with weights of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 units, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English Imperial ounce or Greek uncia, and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871. However, actual weights were not uniform throughout the area. The weights and measures later used in Kautilya's Arthashastra (4th century BC) are the same as those used in Lothal.[29]

Unique Harappan inventions include an instrument which was used to measure whole sections of the horizon and the tidal dock. In addition, Harappans evolved new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead and tin. The engineering skill of the Harappans was remarkable, especially in building docks after a careful study of tides, waves and currents.

In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh, Pakistan made the discovery that the people of the Indus Valley Civilisation, from the early Harappan periods, had knowledge of proto-dentistry. Later, in April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. Eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults were discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Mehrgarh that dates from 7,500-9,000 years ago. According to the authors, their discoveries point to a tradition of proto-dentistry in the early farming cultures of that region."[30]

A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali, which was probably used for testing the purity of gold (such a technique is still used in some parts of India).[31]

Arts and culture

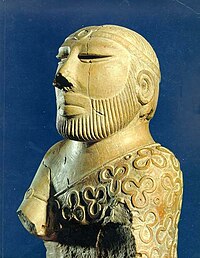

Various sculptures, seals, pottery, gold jewelry and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze and steatite have been found at the excavation sites.

A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form. Sir John Marshall is known to have reacted with surprise when he saw the famous Indus bronze statuette of a slender-limbed "dancing girl" in Mohenjo-daro:

… When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture.. Modeling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3000 years older than those to which they properly belonged. … Now, in these statuettes, it is just this anatomical truth which is so startling; that makes us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus.

Many crafts "such as shell working, ceramics, and agate and glazed steatite bead making" were used in the making of necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments from all phases of Harappan sites and some of these crafts are still practiced in the subcontinent today.[32] Some make-up and toiletry items (a special kind of combs (kakai), the use of collyrium and a special three-in-one toiletry gadget) that were found in Harappan contexts have similar counterparts in modern India.[33] Terracotta female figurines were found (ca. 2800-2600 BCE) which had red color applied to the "manga" (line of partition of the hair), a tradition which is still seen in India.[33]

Seals have been found at Mohenjo-daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another sitting cross-legged in a yoga-like pose (see image, Pashupati, below right).

A harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects found at Lothal indicate the use of stringed musical instruments. The Harappans also made various toys and games, among them cubical dices (with one to six holes on the faces) which were found in sites like Mohenjo-Daro.[34]

Trade and transportation

The Indus civilization's economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. These advances included bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today, as well as boats. Most of these boats were probably small, flat-bottomed craft, perhaps driven by sail, similar to those one can see on the Indus River today; however, there is secondary evidence of sea-going craft. Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal.

During 4300 - 3200 BC of chalcolithic period ( copper age ), Indus Valley Civilization area shows ceramic similarities with southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran which suggest considerable mobility and trade. During Early Harappan period about 3200–2600 BCE, similarities in pottery, seals, figurines, ornaments etc. document intensive caravan trade with Central Asia and the Iranian plateau.[35]

Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilisation artifacts, the trade networks, economically, integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and central India, and Mesopotamia.

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilisations as early as the middle Harappan Phase, with much commerce being handled by "middlemen merchants from Dilmun" (modern Bahrain and Failaka located in the Persian Gulf).[36] Such long-distance sea-trade became feasible with the innovative development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

Several coastal settlements like Sotkagen-dor (astride Dasht River, north of Jiwani), Sokhta Koh (astride Shadi River, north of Pasni) and Balakot (near Sonmiani) in Pakistan along with Lothal in India testify to their role as Harappan trading outposts. Shallow harbours located at the estuary of rivers opening into the sea, allowed brisk maritime trade with Mesopotamian cities.

Agriculture

Post 1980 studies indicate that food production was largely indigenous to the Indus Valley. It is known that the people of Mehrgarh used domesticated wheats and barley[37] and the major cultivated cereal crop was naked six-row barley, a crop derived from two-row barley (see Shaffer and Liechtenstein 1995, 1999). Archaeologist Jim G. Shaffer (1999: 245) writes that the Mehrgarh site "demonstrates that food production was an indigenous South Asian phenomenon" and that the data support interpretation of "the prehistoric urbanization and complex social organization in South Asia as based on indigenous, but not isolated, cultural developments."

This article or section appears to contradict itself. |

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Indus civilization agriculture must have been highly productive; after all, it was capable of generating surpluses sufficient to support tens of thousands of urban residents who were not primarily engaged in agriculture. It relied on the considerable technological achievements of the pre-Harappan culture, including the plough. Still, very little is known about the farmers who supported the cities or their agricultural methods. Some of them undoubtedly made use of the fertile alluvial soil left by rivers after the flood season, but this simple method of agriculture is not thought to be productive enough to support cities. There is no evidence of irrigation, but such evidence could have been obliterated by repeated, catastrophic floods.[citation needed]

The Indus civilization appears to contradict the hydraulic despotism hypothesis of the origin of urban civilization and the state. According to this hypothesis, all early, large-scale civilizations arose as a by-product of irrigation systems capable of generating massive agricultural surpluses. [citation needed]

It is often assumed that intensive agricultural production requires dams and canals. This assumption is easily refuted. Throughout Asia, rice farmers produce significant agricultural surpluses from terraced, hillside rice paddies, which result not from slavery but rather the accumulated labor of many generations of people. Instead of building canals, Indus civilization people may have built water diversion schemes, which—like terrace agriculture—can be elaborated by generations of small-scale labour investments. It should be noted that only the easternmost section of the Indus Civilisation people could build their lives around the monsoon, a weather pattern in which the bulk of a year's rainfall occurs in a four-month period; others had to depend on the seasonal flooding of rivers caused by snow melt at high elevations.[citation needed]

Writing or symbol system

Well over 400 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals or ceramic pots and over a dozen other materials, including a "signboard" that apparently once hung over the gate of the inner citadel of the Indus city of Dholavira. Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which (aside from the Dholavira "signboard") are exquisitely tiny; the longest on a single surface, which is less than 1 inch (2.54 cm) square, is 17 signs long; the longest on any object (found on three different faces of a mass-produced object) has a length of 26 symbols.

While the Indus Valley Civilization is often characterized as a "literate society" on the evidence of these inscriptions, this description has been challenged on linguistic and archaeological grounds: it has been pointed out that the brevity of the inscriptions is unparalleled in any known premodern literate society. Based partly on this evidence, a controversial paper by Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel (2004)[38] argues that the Indus system did not encode language, but was instead similar to a variety of non-linguistic sign systems used extensively in the Near East and other societies. It has also been claimed on occasion that the symbols were exclusively used for economic transactions, but this claim leaves unexplained the appearance of Indus symbols on many ritual objects, many of which were mass produced in molds. No parallels to these mass-produced inscriptions are known in any other early ancient civilizations.[39]

Photos of many of the thousands of extant inscriptions are published in the Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (1987, 1991), edited by A. Parpola and his colleagues. Publication of a final third volume, which will reportedly republish photos taken in the 1920s and 1930s of hundreds of lost or stolen inscriptions, along with many discovered in the last few decades, has been announced for several years, but has not yet found its way into print. For now, researchers must supplement the materials in the Corpus by study of the tiny photos in the excavation reports of Marshall (1931), Mackay (1938, 1943), Wheeler (1947), or reproductions in more recent scattered sources.

Religion

In view of the large number of figurines found in the Indus valley, it has been suggested that the Harappan people worshipped a Mother goddess symbolizing fertility; however, this interpretation is not unanimously accepted. Some Indus valley seals show swastikas which are found in other later religions and mythologies. In the earlier phases of their culture, the Harappans buried their dead; however, later, especially in the cemetery H culture of the late Harrapan period, they also cremated their dead and buried the ashes in burial urns. Many Indus valley seals show animals; for example, a seal showing a figure seated in a yoga-like posture and surrounded by animals has been compared to the "lord of creatures," Pashupati.

Late Harappan

Around 1800 BCE, signs of a gradual decline began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned. However, the Indus Valley Civilization did not disappear suddenly, and many elements of the Indus Civilization can be found in later cultures. Current archaeological data suggests that material culture classified as Late Harappan may have persisted until at least c. 1000-900 BCE, and was partially contemporaneous with the Painted Grey Ware and perhaps early NBP cultures.[40] Archaeologists have emphasised that just as in most areas of the world, there was a continuous series of cultural developments. These link "the so-called two major phases of urbanisation in South Asia".[40]

A possible natural reason for the IVC's decline is connected with climate change: The Indus valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE. A crucial factor may have been the disappearance of substantial portions of the Ghaggar Hakra river system. A tectonic event may have diverted the system's sources toward the Ganges Plain, though there is some uncertainty about the date of this event. Although this particular factor is speculative, and not generally accepted, the decline of the IVC, as with any other civilisation, will have been due to a combination of various reasons.[citation needed]

Legacy

This article may need to be cleaned up. It has been merged from (link). |

In the course of the 2nd millennium BCE, remnants of the IVC's culture would (the so-called Cemetery H culture) amalgamate with those of Indo-Aryan peoples according to Indo Aryan Invasion or Migration theory, likely contributing to what eventually resulted in the rise of Vedic culture and eventually historical Hinduism. Judging from the abundant figurines, which may depict female fertility, that they left behind, some assume that IVC people worshipped a Mother goddess (compare Shakti and Kali, several thousands years later). However, there is no firm agreement among experts as to whether or not these figurines actually depict female fertility, or if they depict something else. Also these people ate beef and buried their dead. IVC seals depict animals, perhaps as the objects of veneration, comparable to the zoomorphic aspects of some Hindu gods. Seals that some think resemble Pashupati in a yogic posture have also been discovered.

In the aftermath of the Indus Civilization's collapse, regional cultures emerged, to varying degrees showing the influence of the Indus Civilization. In the formerly great city of Harappa, burials have been found that correspond to a regional culture called the Cemetery H culture. At the same time, the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture expanded from Rajasthan into the Gangetic Plain. The Cemetery H culture has the earliest evidence for cremation, a practice dominant in Hinduism until today.

See also

- Sokhta Koh - A Coastal Harappan Settlement

- Meluhha - a place name used in Mesopotamia which may have referred to the Indus Civilisation

- Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures

Notes

- ^ "Indus civilization". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-16.

- ^ a b Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521430798.

- ^ Ching, Francis D. K. (2006). A Global History of Architecture. Hoboken, N.J.: J. Wiley & Sons. pp. pp. 28–32. ISBN 0471268925.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ Ratnagar, Shereen (2006). Trading Encounters: From the Euphrates to the Indus in the Bronze Age. Oxford University Press, India. ISBN 019568088X.

- ^ Masson, Charles (1842). "Chapter 2: Haripah". Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab; including a residence in those countries from 1826 to 1838. London: Richard Bentley. pp. p. 472.

A long march preceded our arrival at Haripah, through jangal of the closest description.... When I joined the camp I found it in front of the village and ruinous brick castle. Behind us was a large circular mound, or eminence, and to the west was an irregular rocky height, crowned with the remains of buildings, in fragments of walls, with niches, after the eastern manner.... Tradition affirms the existence here of a city, so considerable that it extended to Chicha Watni, thirteen cosses distant, and that it was destroyed by a particular visitation of Providence, brought down by the lust and crimes of the sovereign.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) Note that the coss, a measure of distance used from Vedic to Mughal times, is approximately 2 miles. - ^ a b

Indus Valley (1976). "Robert Davreau". In World's Last Mysteries, Reader's Digest.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1991). "The Indus Valley tradition of Pakistan and Western India". Journal of World Prehistory. 5: 1–64.

- ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ Chandler, Graham (1999). "Traders of the Plain". Saudi Aramco World: 34–42.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dales, George F. (1962). "Harappan Outposts on the Makran Coast". Antiquity. 36 (142): 86.

- ^ Rao, Shikaripura Ranganatha (1973). Lothal and the Indus civilization. London: Asia Publishing House. ISBN 0210222786.

- ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hassan (1970–1971). "Excavations in the Gomal Valley". Ancient Pakistan (5): 1–177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Joshi, J. P. (1982). "Manda: A Harappan site in Jammu and Kashmir". In Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.) (ed.). Harappan Civilization: A recent perspective. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 185–95.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Indian Archaeology, A Review. 1958-1959. Excavations at Alamgirpur. Delhi: Archaeol. Surv. India, pp. 51-52.

- ^ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2003). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0521011094.

- ^ Dales, George F. (1979). "The Balakot Project: summary of four years excavations in Pakistan". In Maurizio Taddei (ed.) (ed.). South Asian Archaeology 1977. Naples: Seminario di Studi Asiatici Series Minor 6. Instituto Universitario Orientate. pp. 241–274.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Bisht, R. S. (1989). "A new model of the Harappan town planning as revealed at Dholavira in Kutch: a surface study of its plan and architecture". In Chatterjee, Bhaskar (ed.) (ed.). History and Archaeology. New Delhi: Ramanand Vidya Bhawan. pp. 379–408. ISBN 8185205469.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Possehl, Gregory L. (1990). "Revolution in the Urban Revolution: The Emergence of Indus Urbanization". Annual Reviews of Anthropology (19): 261–282 (Map on page 263).

- ^ Mughal, M. R. 1982. "Recent archaeological research in the Cholistan desert". In Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.) (ed.). Harappan Civilization. Delhi: Oxford & IBH &

A.I.1.S. pp. 85–95.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); line feed character in|publisher=at position 15 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Shaffer, Jim G. (1989). "Ethnicity and Change in the Indus Valley Cultural Tradition". Old Problems and New Perspectives in the Archaeology of South Asia. Wisconsin Archaeological Reports 2. pp. 117–126.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ e.g. Misra, Virendra Nath (1992). Indus Civilization, a special Number of the Eastern Anthropologist. pp. 1–19.

- ^ Ratnagar, Shereen (2006). Understanding Harappa: Civilization in the Greater Indus Valley. New Delhi: Tulika Books. ISBN 8189487027.

- ^ Durrani, F. A. (1984). "Some Early Harappan sites in Gomal and Bannu Valleys". In Lal, B. B. and Gupta, S. P. (ed.). Frontiers of Indus Civilisation. Delhi: Books & Books. pp. 505–510.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Thapar, B. K. (1975). "Kalibangan: A Harappan Metropolis Beyond the Indus Valley". Expedition. 17 (2): 19–32.

- ^ It has been noted that the courtyard-pattern and techniques of flooring of Harappan houses has similarities to the way house-building is still done in some villages of the region. Template:Wikiref

- ^ Sergent, Bernard (1997). Genèse de l'Inde (in French). p. 113. ISBN 2228891169.

- ^ Coppa, A. (2006-04-06). "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population" (PDF). Nature. 440.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Bisht, R. S. (1982). "Excavations at Banawali: 1974-77". In Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.) (ed.). Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. pp. 113–124.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1997). "Trade and Technology of the Indus Valley: New Insights from Harappa, Pakistan". World Archaeology. 29 (2: "High-Definition Archaeology: Threads Through the Past"): 262–280.

- ^ a b Template:Wikiref

- ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ Template:Wikiref

- ^ Neyland, R. S. (1992). "The seagoing vessels on Dilmun seals". In Keith, D.H.; Carrell, T.L. (eds.) (ed.). Underwater archaeology proceedings of the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference at Kingston, Jamaica 1992. Tucson, AZ: Society for Historical Archaeology. pp. 68–74.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Jarrige, J.-F. (1986). "Excavations at Mehrgarh-Nausharo". Pakistan Archaeology. 10 (22): 63–131.

- ^ Farmer, Steve; Sproat, Richard; Witzel, Michael. "The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ These and other issues are addressed in Template:Wikiref

- ^ a b Shaffer, Jim (1993). "Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond". In Spodek, Howard; Srinivasan, Doris M. (ed.). Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

Bibliography

- Allchin, Bridget (1997). Origins of a Civilization: The Prehistory and Early Archaeology of South Asia. New York: Viking.

- Allchin, Raymond (ed.) (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Aronovsky, Ilona (2005). The Indus Valley. Chicago: Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Basham, A. L. (1967). The Wonder That Was India. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 11–14.

- Chakrabarti, D. K. (2004). Indus Civilization Sites in India: New Discoveries. Mumbai: Marg Publications. ISBN 81-85026-63-7.

- Dani, Ahmad Hassan (1984). Short History of Pakistan (Book 1). University of Karachi.

- Dani, Ahmad Hassan (1996). History of Humanity, Volume III, From the Third Millennium to the Seventh Century BC. New York/Paris: Routledge/UNESCO. ISBN 0415093066.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gupta, S. P. (1996). The Indus-Saraswati Civilization: Origins, Problems and Issues. ISBN 81-85268-46-0.

- Gupta, S. P. (ed.) (1995). The lost Sarasvati and the Indus Civilisation. Jodhpur: Kusumanjali Prakashan.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Kathiroli (2004). "Recent Marine Archaeological Finds in Khambhat, Gujarat". Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology (1): 141–149.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998). Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-577940-1.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1991). "The Indus Valley tradition of Pakistan and Western India". Journal of World Prehistory. 5: 1–64.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195174224.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kirkpatrick, Naida (2002). The Indus Valley. Chicago: Heinemann.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (ed.) (2000). The Decline and Fall of the Indus Civilisation. ISBN 81-7530-034-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Lal, B. B. (1998). India 1947-1997: New Light on the Indus Civilization. ISBN 81-7305-129-1.

- Lal, B. B. (1997). The Earliest Civilisation of South Asia (Rise, Maturity and Decline).

- Lal, B. B. (2002). The Sarasvati flows on.

- McIntosh, Jane (2001). A Peaceful Realm: The Rise And Fall of the Indus Civilization. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0813335329.

- Mughal, Mohammad Rafique (1997). Ancient Cholistan, Archaeology and Architecture. Ferozesons. ISBN 9690013505.

- Parpola, Asko (2005-05-19). "Study of the Indus Script" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) (50th ICES Tokyo Session) - Possehl, Gregory (2002). The Indus Civilisation. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press.

- Rao, Shikaripura Ranganatha (1991). Dawn and Devolution of the Indus Civilisation. ISBN 81-85179-74-3.

- Shaffer, Jim G. (1995). "Cultural tradition and Palaeoethnicity in South Asian Archaeology". In George Erdosy (ed.) (ed.). Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia. ISBN 3-11-014447-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Shaffer, Jim G. (1999). "Migration, Philology and South Asian Archaeology". In Bronkhorst and Deshpande (eds.) (ed.). Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia. ISBN 1-888789-04-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Shaffer, Jim G. (1992). "The Indus Valley, Baluchistan and Helmand Traditions: Neolithic Through Bronze Age". In R. W. Ehrich (ed.) (ed.). Chronologies in Old World Archaeology (Second Edition ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|editor=has generic name (help) - Witzel, Michael (2000). "The Languages of Harappa" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Harrapa and Indus Valley Civilisation at harrapa.com

- An invitation to the Indus Civilisation (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum)

- The Harappan Civilisation

- Why Perpetuate Myths ? - A Fresh Look at Ancient Indian History - By B. B. Lal - Director General (Retd.) - Archaeological Survey of India

- The Homeland of Indo-European Languages and Culture: Some Thoughts By B.B. Lal

- The Indus-Sarasvati Civilization Essay by Michel Danino

- Indus Artifacts

- Indus-Sarasvati Resources Index

- Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilisation

- Cache of Seal Impressions Discovered in Western India