Watchmen

| Watchmen | |

|---|---|

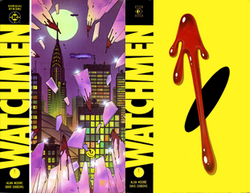

Cover art for the 1987 U.S. (left) and UK (right) collected editions of Watchmen, published by DC Comics and Titan Books. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Format | Limited series |

| Publication date | September 1986 – October 1987 |

| No. of issues | Twelve |

| Main character(s) | Second Nite Owl Dr. Manhattan Rorschach Second Silk Spectre Ozymandias Comedian |

| Creative team | |

| Written by | Alan Moore |

| Artist(s) | Dave Gibbons |

| Colorist(s) | John Higgins |

Watchmen was a twelve-issue comic book written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons. Originally published by DC Comics as a monthly limited series from 1986 to 1987,[1] it was later republished as a trade paperback.[2] It was one of the first superhero comics to present itself as serious literature, and it also popularized the more adult-oriented "graphic novel" format. Watchmen is the only graphic novel to win a Hugo Award,[3] and is also the only graphic novel to appear on Time magazine's 2005 list of "the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to the present."[1]

Watchmen is set in 1985 in an alternative history United States where costumed adventurers are real and the country is edging closer to a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. It tells the story of the last remaining superheroes and the events surrounding the mysterious murder of one of their own. In Watchmen, superheroes are presented as real people who must confront ethical and personal issues, who have neuroses and failings, and who are largely lacking in superpowers. Watchmen's deconstruction of the conventional superhero archetype, combined with its innovative adaptation of cinematic techniques and heavy use of symbolism and multi-layered dialogue, has changed both comics and film.

Background

Alan Moore, who wanted to transcend the perceptions of the comic book medium as something juvenile, created Watchmen as an attempt to make "a superhero Moby Dick; something that had that sort of weight, that sort of density."[4] Moore also named William S. Burroughs as one of his "main influences" during the conception of Watchmen and admired Burroughs' use "of repeated symbols that would become laden with meaning" in Burroughs's one and only comic strip, which appeared in the British underground magazine Cyclops.[4]

Moore and Gibbons originally conceived of a story that would take "familiar old-fashioned superheroes into a completely new realm."[5] Dick Giordano, who had worked for Charlton Comics, suggested using a cast of old Charlton characters that had recently been acquired by DC; but since Moore and Gibbons wanted to do a serious story-line in which some of the newly acquired characters would die, this was not feasible. Giordano then suggested that Moore and Gibbons simply start from scratch and create their own characters. So while certain characters in Watchmen are loosely based upon the Charlton characters (such as Dr. Manhattan, who was inspired by Captain Atom; Rorschach, who was loosely based upon the Question; and Nite Owl, who was loosely based on the Blue Beetle), Moore decided to create characters that ultimately would scarcely resemble their Charlton counterparts.

Originally, Moore and Gibbons only had enough plot for six issues, so they compensated "by interspersing the more plot-driven issues with issues that gave kind of a biographical portrait of one of the main characters."[6] During the process, Gibbons had a great deal of autonomy in developing the visual look of Watchmen and inserted details that Moore admits he did not notice until later, as Watchmen was written to be read and fully understood only after several readings.[4]

Composition

Title

The title Watchmen is derived from the phrase quis custodiet ipsos custodes, from Juvenal's Satire VI, "Against women" (c. AD 60-127), often translated as "Who watches the watchmen?"

|

|

Juvenal was credited with exposing the vice of Roman society through his satires,[7] and in a similar fashion, Watchmen examines the trope of the costumed adventurer, or superhero, by examining the human flaws of its "superhero" characters in lieu of the traditional comic book focus on its characters' strengths.[8] In Watchmen, Moore shows a "grittier" side to the conceived notion of the superhero.[9]

The graffito "WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN" appears scrawled upon walls throughout New York City during the story, but the complete phrase is never seen; the sentence is always partially obscured or cut out of the panel. The graffito occurs following the proposition of legislation which would require superhero registration, depicting the change of public opinion towards the practice of vigilantism. This viewpoint is exemplified by the character of the second Nite Owl, who asks, during an anti-vigilantism riot, "Who are we protecting [society] from?"[10] As if to illustrate the many problems with vigilantes who sometimes serve as judge, jury and executioner, the Comedian glibly replies, "From themselves."[10]

The title, therefore, refers to the idea of superheroes, police, the government, any who assume the responsibility of protecting the people from themselves. It does not refer to any group of characters within the Watchmen universe. The heroes belong to either the 30's-era supergroup The Minutemen or the short-lived 60's group The Crime-Busters.

Structure

The graphic novel Watchmen is composed of twelve chapters. These chapters were originally separate issues of the comic book series, which were released sequentially starting in 1986. Each chapter begins with a close-up of the first panel, originally the cover to each issue. Each chapter has an epigraph from classical or pop literature, which appears in abbreviated form early on, and acts as the chapter's heading or title. The quote is given in its entirety at the end of the chapter, summarising the events that have just occurred.

Watchmen also contains many fictional primary documents, which are appended to the end of every chapter (except the final one), and represented as being a part of the Watchmen universe's media. Biographies of retired costumed adventurers, such as the retrospective Under the Hood by the retired first Nite Owl, are used to help the reader understand the chronology of events, and also the changes in public opinion and representation of costumed adventurers through the decades. These documents are also used to reveal personal details of the costumed adventurers' private lives, such as Rorschach's arrest record and psychiatric report. Other documents used in this way include military reports and newspaper and magazine articles.

Watchmen's structure has been analysed by many reviewers, with The Friday Review calling Watchmen "a complex, multi-layered narrative, populated with well-realised characters and set against a background that is simultaneously believable and unfamiliar".[11]

Perspective

When reading Watchmen, the reader is mostly presented with only an objective Point of View, able to see all the characters' actions, facial expressions, and body language; but, in a move unusual for comic books of its time, Moore did not rely much upon thought balloons to clarify his characters' thoughts[12], although several sections comprise large episodes dedicated to the characters' memories. The documents that are appended to the end of each chapter (except the last), as well as media such as Rorschach's diary, help to elucidate characters' thoughts and feelings throughout the novel, without mentioning them explicitly.[13] This is in keeping with Watchmen's largely cinematic presentation.

First person perspective is also used, albeit more infrequently. Flashbacks are employed to help facilitate the reader's understanding of events occurring in the present, but also as a means of chronicling the differences in history between the Watchmen universe and our own. Thus, Dr. Manhattan's flashback to the Vietnam War highlights how both his and the Comedian's existence altered their world's history in comparison to our own.[14]

"Watchmen Observations" notes that Watchmen uses a three by three panel structure and that there is little variation in this format. The effect is to "reduce the scope for authorial voice--the reader has fewer clues how she should react to each scene; also, they heighten the feeling of realism and distance the novel from standard action comics."

Story

Characters

The cast of Watchmen was initially based upon old Charlton Comics characters. Moore and Gibbons agreed that Watchmen required a cast of characters that had continuity and a history upon which a story could be based. DC Comics had recently acquired the rights to some old Charlton Comics characters. This prompted former DC Editing Manager Dick Giordano to suggest that Moore use some of these characters. However, to avoid continuity issues with the recently acquired characters, and due to the fact that some of them would have become useless for future series, Moore decided to create new characters, using the recently acquired Charlton Comics characters as templates. This allowed for a more dynamic and unique set of characters. The Comedian (Edward Blake) is based on Peacemaker with elements of Marvel Comics' Nick Fury. Doctor Manhattan (Jon Osterman) is derived from Captain Atom, while the first and second Nite Owls (Hollis Mason and Dan Dreiberg) are based upon Blue Beetle. Thunderbolt serves as the inspiration for Ozymandias (Adrian Veidt), while the Question and Mr. A do the same for Rorschach (Walter Kovacs). Finally, the first and second Silk Spectres (Sally Jupiter and Laurie Juspeczyk) are based on Nightshade with elements of Black Canary and Phantom Lady.[15][16]

Although the cast of Watchmen are commonly called "superheroes," the only superhuman character in the principal cast is Dr. Manhattan — the others are normal human beings with no special abilities aside from peak physical condition and access to high-class technology and weapons. In the comic, they refer to themselves as "costumed adventurers."

Plot summary

In October 1985, Walter Kovacs (Rorschach) investigates the murder of New Yorker Edward Blake and discovers that Blake was the "Comedian," a veteran costumed adventurer and government agent. Forming a theory that Blake's murder is part of a greater plot to eliminate costumed adventurers (or "masks," as Rorschach calls them), Kovacs warns others: Jon Osterman (Dr. Manhattan), Laurel Jane Juspeczyk (the second Silk Spectre), Dan Dreiberg (the second Nite Owl) and Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias). Veidt, Juspeczyk and Dreiberg are long retired from crime-fighting, the latter two because of the 1977 passage of the Keene Act, which had banned costumed vigilantes (a law that Kovacs, deeply immersed in his Rorschach identity and uncompromising moral code, ignores). Veidt retired voluntarily in 1975, disclosing his identity publicly and using his reputation and intelligence to build a successful commercial enterprise and a large personal fortune. Like Blake, Osterman remained exempt from the Keene Act as an agent of the U.S. government. He no longer engages in crimefighting, having become an important element of the ongoing Cold War.

The United States and the Soviet Union have been edging toward a nuclear showdown since the 1959 nuclear accident that transformed Osterman into the super-powered Dr. Manhattan. Due to Osterman's near-godlike powers and allegiance to the American government, the U.S. has enjoyed a distinct strategic advantage, allowing it to defeat the Soviet Union in a series of proxy wars -- most notably in Vietnam. This imbalance dramatically increased global tension. In seeming anticipation of global war, American society has assumed a general sense of fatalism about the future. Signs of this in daily life range from "Meltdowns" candy to graffiti inspired by the Hiroshima bombing to the designation of many buildings in New York as fallout shelters.

Veidt, observing Osterman's increasing emotional detachment from humanity, forms a theory that military expenditures and environmental damage will lead to global catastrophe no later than the mid-1990s. As part of an elaborate plot to avert this, Veidt acts to accelerate Osterman's isolation by secretly exposing more than two dozen of Osterman's former associates to harmful radiation, inflicting a variety of cancers on them. Meanwhile, Veidt manipulates the press into speculating that Osterman himself was the cause of these cancers.

Now hounded by media allegations and quarantined as a result, Osterman teleports himself to the planet Mars to contemplate the events of his life. His break with the U.S. government prompts Soviet opportunism in the form of an invasion of Afghanistan (a delayed version of the real-life event), greatly aggravating the global crisis; as the situation continues to escalate, the U.S. government and public alike realize that nuclear war could be only days away. Investigating the calamities that have befallen other heroes, Dreiberg and Kovacs discover information incriminating Veidt; Kovacs, Juspeczyk, Osterman and Dreiberg confront Veidt at his Antarctic retreat, but too late to prevent the final phase of his plan. Using a teleportation device, Veidt moves a massive, genetically-engineered, psionic creature into the heart of New York City, knowing that the teleportation process would kill it. In its death-throes, the creature releases a "psychic shockwave" containing imagery designed to be so violent and alien as to kill half the residents of the city and drive many survivors insane. With the world convinced that the creature is the first of a potential alien invasion force, the United States and Soviet Union withdraw from the brink of war and form an accord to face this apparent extraterrestrial threat.

The murderer of Blake is revealed to be Veidt himself, acting after Blake had accidentally discovered details of Veidt's plot. Veidt has also eliminated numerous employees and minions. At the end, the only people aware of the truth are Veidt, Dreiberg, Juspeczyk, Kovacs and Osterman. Dreiberg, Juspeczyk and Osterman agree to keep silent out of concern that revealing the plot could re-ignite U.S.–Soviet tensions, but Kovacs refuses to compromise and is killed by Osterman.

The ending is deliberately ambiguous about the long-term success of Veidt's plan to lead the world to utopia. After killing Kovacs, Osterman talks briefly to Veidt. Professing his guilt and doubt, Veidt asks the omniscient Osterman for closure: "I did the right thing, didn't I? It all worked out in the end." Osterman, standing within Veidt's mechanical model of the solar system, replies cryptically: "In the end? Nothing ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends." He then disappears, leaving Earth forever and leaving the entire orrery framed by a residue appearing distinctly similar to an atomic mushroom cloud.

However, before confronting Veidt, Kovacs had mailed his journal detailing his suspicions to The New Frontiersman, a far right-wing magazine Kovacs frequently read. The final frame of the series shows a New Frontiersman editor contemplating which item from the "crank file" (to which Kovacs's journal had been consigned) to use as filler for the upcoming issue.

Tales of the Black Freighter

Tales of the Black Freighter is a comic book within the Watchmen universe, an example of post-modern metafiction that also serves as a foil for the main plot. The specific issues shown in Watchmen chronicle a castaway's increasingly desperate attempts to return home to warn his family of the impending arrival of the Black Freighter, a phantom pirate ship which houses the souls of the dead. As the man's journey progresses, he becomes more and more unscrupulous, attempting to justify his increasingly irrational, paranoid disposition, and his criminal acts.

A pirate comic book was conceived by Moore because he and Gibbons thought that since the inhabitants of the Watchmen universe experience superheroes in real life, then "they probably wouldn't be at all interested in superhero comics."[17] A pirate theme was suggested by Gibbons, and Moore agreed because he is "a big Brecht fan."

The comic is being read by a teenage boy whilst he sits beside a newsstand, whose proprietor, meanwhile, contemplates the latest news headlines and discusses them with his customers. This juxtaposition of text and images from the story within a story and its framing sequence uses the former to act as a parallel commentary to the latter — which is the plot of Watchmen itself.[18] Specifically, Moore has said that the story of The Black Freighter ends up describing "the story of Adrian Veidt" (who admits, in his final scene, to having a recurring nightmare resembling a prominent image from The Black Freighter. In addition, the comic can also be seen to relate "to Rorschach and his capture; it relates to the self-marooning of Dr. Manhattan on Mars; it can be used as a counterpoint to all these different parts of the story."[17] Moore also intended the opening panel in Chapter III to reinforce the reader's identification with the radioactive warning trefoil; Moore thought that the close-up of the trefoil in the first panel looked like a "stylised picture of a black ship". The trefoil then came to represent "a black ship against a yellow sky."

Artwork

Penciller and inker Dave Gibbons and colorist John Higgins are credited with giving life to the various characters in Watchmen. They employed a variety of innovative techniques, a style that contained elements of the Golden Age of Comics and a deliberate attempt to inject cinematic realism, uncommon in comic-books in the 1980s. Gibbons, who had worked with Moore on previous occasions, including a notable 1985 Superman story (Annual 11, "For the Man Who Has Everything"), avoided convention in his work and developed a storyboard-like style to present the dialogue written by Moore. Nearly every panel includes significant details of the story-line or visual motifs (such as triangles and pyramids) with themes important to the plot.[19] Gregory J. Golda describes the artwork as "both a tribute to the Gold and Silver Age style[s] of super hero comics." He also writes that there "are symbols embedded in this work that require a book to fully discover."[20] Gibbons used other cinematic techniques such as having two main characters somewhat obscured by their surroundings and background characters in order to avoid the usual extreme focus upon the primary characters prevalent in most comicbook art.[21] Moreover, Watchmen rarely uses motion lines to indicate motion, another technique often utilised in the comic book industry.[22] In Watchmen, motion lines are only used to indicate small actions, and are not utilised in fight scenes. Instead, Gibbons uses "posture and blood" to highlight the motion and movement of the characters, which "[adds] to the feel of realism and [limits the] authorial voice"[23] Also missing are the written, onomatopoetic sound effects that are a traditional comic book storytelling technique.

Gibbons described his design of the characters as his own, derived from Moore's character notes. Moore credits Gibbons with coming up with many of the signature symbols in Watchmen, including the iconic smiley face, which was "derived from behavioural psychology tests. They tried to find the simplest abstraction that would make a baby smile."[4] Contrary to popular opinion, Gibbons contends that Rorschach's subtle body language and not his Rorschach test-inspired mask are the real indications of his mood.[24] In addition, John Higgins' colouring technique was to rely upon primary colors, again indicative of the Golden Age style, rather than a wider colour selection.[25]

Gibbons, who had no formal art training, notes among his inspirations Norman Rockwell, who was sometimes described as an illustrator with an idealized portraiture style, and Jack Kirby.[26] The art, while deriving inspiration from various predecessors including Will Eisner and Wally Wood (also named by Gibbons as major influences), is at once original in its execution and can be seen as a precursor to later 'realistic' comic book artists such as Alex Ross.

Themes

Realism is a primary mode in Watchmen, which features themes that relate superheroes to the human condition. Moore explores the fantastic world of costumed adventurers by raising various social issues that begin with the perception of authority. The novel's examination of trust in authority can be summed up in the phrase, "Who watches the Watchmen?" In a Weberian sense, authority is seldom endorsed morally by those who do not have it, with institutionalized authority being unchallenged simply due to intrinsic aspects of social power. The vigilantes in Watchmen, before the Keene Act, represent superheroes as an institution, generally unquestioned until the issues of responsibility and culpability are raised. This questioning of authority mirrors the Opposition to the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement, both of which are discussed in Watchmen.

These ideas are also apparent in what post-modernist Gregory J. Golda calls the "anti-veneration" throughout the novel, illustrated by depicting superheroes as "cranky and inept old timers". Golda's anti-veneration "treats destructive societal norms as the direct responsibility of the viewer by attacking the principles society holds most dear. This lack of respect for the past is the crux of the Watchmen."[20]

The subject of anti-veneration explores superheroes who are treated as veritable gods to be worshipped at one point (with Dr. Manhattan taking on the literal manifestation of a deity) and then are deconstructed in order to reveal flaws, which makes them less worthy of hero worship in the eyes of the public. Nonetheless, heroes can still be worthy within the valetism form of hero worship as theorised by essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle and expressed in Watchmen.[27] Carlyle, who was influential on early fascist philosophy, developed a concept of hero worship that was meant to overlook human flaws, as he contended that there was no need for "moral perfection."[28] Along these lines, Rorschach even belittles what he terms as "moral lapses" when discussing the Comedian's past acts of violence.[29] These Carlyle-inspired ideas are depicted throughout Watchmen, as Ozymandias, during a discussion with Rorschach, refers to the Comedian as "a Nazi."[30] To further exemplify this issue of superheroes as fascists, the extreme right-wing publication New Frontiersman appears to be the most ardent supporter of masked vigilantism with one headline reading, "Honor is like the Hawk: Sometimes it must go Hooded."[31]

Apocalypticism and conspiracy theory are elements of both plot and mood in the series. The threat of nuclear annihilation is ever-present throughout the novel. According to an interpretation by director Darren Aronofsky, "the whole motivation for Ozymandias is the impending doom of the world."[32] The plot is based around a conspiracy. Rorschach is obsessed with conspiracy theories, and appears to derive much of his thinking from the New Frontiersman. Aronofsky argues that Watchmen's treatment of the subject was pioneering, but has since "become so 'pop' because of JFK and The X-Files, it’s entered pop culture consciousness, and Rorschach’s vision is not that wacky any more."[32]

Conspiracy theories invoke a lack of control on the part of characters like Rorschach and lead to the examination of other themes in Watchmen, such as determinism. Gregory J. Golda describes the relationship between the philosophy of determinism and Dr. Manhattan, who "lives his now immortal life with a perception of time and events as unchangeable. He becomes the symbol of Determinism" and "lives his own life under this illusion of determinism[,] failing to see that there was a superior intellect that could outsmart even an 'all knowing' being."[20] This ties into notions of free will as discussed by Thomas Hobbes, a prominent philosopher of determinism and human nature. Hobbesian views tended to support the notion that there was no absolute free will as Hobbes "was a determinist in the sense that [he espoused that] although one's actions are free, one's will is not."[33] It is often Dr. Manhattan who discusses issues of determinism and free will, as when he explains to Silk Spectre II, "We're all puppets, Laurie. I'm just a puppet who can see the strings."[34]

Watchmen also explores issues dealing with memory by utilizing flashbacks, which define the characters and how they are remembered by their peers.[35] For example, the past actions of the Comedian are all selectively recalled by Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and Nite Owl II as each recalls some significant event that defined who the Comedian was to them and how he influenced them. Further flashbacks by Dr. Manhattan and the first and second Silk Spectres also relate to the power of memories as they serve to provide epiphanies or an idealised past. "Even the grimy parts of it, well, it just keeps on getting brighter all the time," as the retired first Silk Spectre explains to her daughter.[36] It is Rorschach, though, who constructs the most idyllic past, with a father he never knew and an idealized portrayal of President Truman.[37]

Megalomania is also addressed in Watchmen, but not with conventional "villains". Instead, Ozymandias is presented as an idealist who looks to the past for inspiration so that he may better utilise his prodigious intellect to help mankind. At first idolising Alexander the Great, he later relates himself to Ramses II (and adopts his Greek name Ozymandias) and the golden age of the Pharaohs.[38] This has parallels with the Golden Age superhero Hawkman, who believed himself to be the reincarnation of an Egyptian prince as well. Ozymandias exhibits various aspects of Narcissistic Personality Disorder including behavioural grandiosity and a lack of empathy.[39]

Many of the themes in Watchmen are explored in Moore's other works, including V for Vendetta, which also dealt with issues relating to fascism and hero worship. In addition, Nietzchian themes are often evidenced: the Übermensch (literally, "Overman," but more colloquially and to the point, "Superman") recurs throughout much of Moore's work, including Dr. Manhattan in Watchmen, Miracleman, and Tom Strong. Likewise, Osterman's final words in regards to the nature of the universe, "Nothing ever ends," are a succinct expression of Nietzsche's philosophy of eternal recurrence.

Significance

Reception and criticism

In 2005, Time magazine placed Watchmen on its list of the 100 Greatest English Language Novels from 1923 to the Present, stating that it was "told with ruthless psychological realism, in fugal, overlapping plotlines and gorgeous, cinematic panels rich with repeating motifs...a heart-pounding, heartbreaking read and a watershed in the evolution of a young medium." Watchmen was the only graphic novel to be listed.[1] Watchmen has also received several awards spanning different categories and genres including: Kirby Awards for Best Finite Series, Best New Series, Best Writer, and Best Writer/Artist, Eisner Awards for Best Finite Series, Best Graphic Album, Best Writer, and Best Writer/Artist, and a Hugo Award for Special Achievement.

Watchmen received praise from those working within the comic book industry, as well as external reviewers, for its avant-garde portrayal of the traditional superhero. Watchmen became known as a novel which allowed the comic book to be recognised as "great art," rather than a low brow or unsophisticated genre.[40] Don Markstein of Toonopedia wrote that, "What The Maltese Falcon did for detective stories and Shane did for Westerns, Watchmen did for superheroes. It transcended its origins in what was previously considered a low brow form of fiction."[41]

Watchmen's status as a seminal book in the comic book field was recently boosted when acclaimed comic book author Stan Lee called it his "all-time favorite comic book outside of Marvel."[42] A review by "Revolution SF" goes on to say that Watchmen is "one of the most important stories in comic book history..."[42]

There has also been some criticism of Watchmen. In terms of the artwork, the colours have been characterized as "flat" and too "contrasting" by one reviewer.[43] There has been some questioning of the complexity of Watchmen, as well as Gibbons' involvement in it, saying that he "always felt a bit like the fill-in guy." The same source criticizes the long-term influence of the work, and Alan Moore generally, and asks "did the comic book have to 'grow up'?"[44]

References in other works

Watchmen was parodied by The Simpsons's comic book series Radioactive Man in issue #679 "Who Washes The Washmen's Infinite Secrets Of Legendary Crossover Knight Wars?" (September 1994).

Nite Owl and his ship make a cameo appearance in the third issue of Marvels by Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross. Under the Hood, the book written by original Nite Owl, Hollis Mason, is seen in a shop window, Rorschach is visible in the background of the superhero bar and the recurring graffiti 'Who watches the watchmen' all appear in Kingdom Come, also illustrated by Alex Ross.

In issue 17 of the late-eighties DC series The Question, by Dennis O'Neil and Denys Cowan, the Question reads a Watchmen trade paperback and then contemplates Rorschach's crimefighting ideas and their relationship to his own, finally concluding that "Rorschach sucks" after attempting to employ his methods. This was an intentional irony, as Rorschach's character is partly based on the original Charlton Comics' version of The Question.

In 2004, the movie The Incredibles was released, with reviewers commenting upon themes expressed in the film which seemed to pay homage to Watchmen.[45][46]

The now-defunct Canadian rock band The Watchmen took their name from the comic series; Joey Serlin, their guitarist, is an avowed comics fan.

The British band Pop Will Eat Itself make numerous reference to Watchmen in their songs. "Def Con One" includes the lyric Watchmen, we love you all, and a number of quotes from the comic such as Hup hup heads up, Ground floor coming up and How sick is Dick?. Another of their hits, "Can U Dig It", contains the line, "Alan Moore knows the score," with the video for the song featuring several panels from the comic.

Merchandising and adaptations

- See also: Watchmen (film)

In 1987, Mayfair Games produced two adventure modules based on Watchmen for its DC Heroes role-playing game. These modules, entitled "Who Watches the Watchmen?" and "Taking out the Trash", included background information about the fictional Watchmen universe, approved by Alan Moore. His approval made these publications valuable to fans as the only outside source of supplemental information about the characters in the story (especially minor characters, such as the Minutemen and Moloch).[47]

DC Comics also released a limited edition badge set featuring characters and images from the series, including a replica of the blood-stained smiley face badge worn by The Comedian that was featured so prominently in the story. It is claimed that this badge set caused friction between Moore and DC Comics — DC claimed that they were a "promotional item" and not merchandising, and therefore the company did not have to pay Moore or Gibbons royalties on the sets.[48] Although neither party has stated the exact reason for the withdrawal of the figures, DC Comics did say in a press release that they would not go forward without the author's approval.[49]

A film adaptation has been attempted several times, with none reaching even the casting phase. When Terry Gilliam was attached to direct in the late 1980s he met with Moore and after Gilliam asked "How would you make a film of 'Watchmen'?" Moore responded "Don't."[50] Gilliam eventually abandoned the project declaring it "unmakeable."[51] While Moore said that he felt David Hayter's screenplay to be "as close as I could imagine anyone getting to Watchmen", he stated that he would not have gone to see the final film version, had it ever been made.[52] Alan Moore "refuses to have his name attached to any...films."[53] On June 23 2006 it was confirmed by Warner Bros. Studios that Zack Snyder would direct the big screen adaptation of Watchmen.[54]

Editions

Originally published as twelve individual issues, Watchmen was later reprinted as a graphic novel (ISBN 0930289234). A special hardcover edition was produced by Graphitti Designs in 1987, containing 48 pages of bonus material, including the original proposal and concept art. On 5 October 2005, DC released Absolute Watchmen (ISBN 1401207138), a hardcover edition of Watchmen in the Absolute Edition series, to celebrate its upcoming 20th anniversary. The book features a slipcase as well as restored and recoloured art by John Higgins at Wildstorm FX, under the direction of Dave Gibbons. The new book also includes the bonus material from the Graphitti edition, marking the first time this material has been widely available.

Footnotes and references

- ^ a b c "Time Magazine - ALL-TIME 100 Novels" — A synopsis describing Watchmen (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ Moore, Alan (2006). Watchmen. Titan. ISBN 1852860243.

- ^ "AwardWeb: Hugo Award Winners" - Watchmen listed as a winner of the Hugo Award (retrieved 20 April 2006)

- ^ a b c d "Alan Moore Interview 1988" Johncoulthart.com (retrieved 6 June 2006)

- ^ "The Alan Moore Interview" Blather.net (retrieved 6 June 2006)

- ^ "In League with Alan Moore" Locus Online (retrieved 6 June 2006)

- ^ "MSN Encarta: Satire" - A discussion on "Satire" (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "Ninth Art - Alan Moore" - retrieved 20 April 2006

- ^ "The Craft - an interview with Alan Moore" (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ a b - Watchmen page 17, panel 6 (ISBN 0930289234) Cite error: The named reference "Watchmen pg17" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "The Friday Review" A review of Watchmen - (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "Fanboy Radio" - a discussion on the thought balloon in comic books (retrieved 20 April 2006

- ^ "Shotgun Reviews" - an essay discussing Watchmen (retrieved 20 April 2006)

- ^ Watchmen pages 19 & 20

- ^ "Alan Moore Interview - Comic Book Artist #9" — An interview with Alan Moore (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "Watchmen — Introduction" — An overview of the plot and characters in Watchmen (retrieved 12 March 2006)

- ^ a b "The Alan Moore Interview: Watchmen, microcosms and details" — An interview with Alan Moore (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "Review of Graphic Novels" — A review which describes Tales of the Black Freighter (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "The Annotated Watchmen, Chapter 1: "At Midnight, All the Agents..."" — A panel by panel analysis of Watchmen by Ralf Hildebrandt (retrieved 2 June 2006)

- ^ a b c Golda, Gregory J. (1997). ""Post-modern graphic novels"". Retrieved 2006-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Absolute Watchmen Review, The greatest comic-book ever written has been made even better." — Review by Hilary Goldstein (retrieved 2 June 2006)

- ^ "Comics-Like Motion Depiction in Stereo" - An essay discussing the portrayal of motion in comic books (retrieved 22 April 2006)

- ^ "Watchmen Observations" - retrieved (22 April 2006)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "BBC Book Review, May 2004, 'Midnight In The Garden Of Good And Evil'" — Watchmen reviewed by DJ Bu & The Astrons (retrieved 2 June 2006)

- ^ "Sequential Tart, Volume II, Issue 7, July 1999, 'Under the Hood, Dave Gibbons'" — Interview with Dave Gibbons by Christy Kallies (retrieved 2 June 2006)

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (1997). ""Thomas Carlyle: On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History"". Retrieved 2006-06-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Fascism, Characteristics of Fascist Philosophy," — Columbia Encyclopedia: Fascism (retrieved 4 June 2006)

- ^ - Watchmen chapter 1, page 21, panel 8 (ISBN 0930289234)

- ^ Ibid., Chapter 1, page 17, panel 5

- ^ Ibid., Chapter 8, page 29

- ^ a b Hughes, David (2001). ""Who Watches the Watchmen?"" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thomas Hobbes: 1588-1679, Quotations — Island of Freedom (retrieved 4 June 2006)

- ^ - Watchmen chapter 9, page 5, panel 4 (ISBN 0930289234)

- ^ "Four Color Commentary" — Watchmen (retrieved 5 June 2006)

- ^ - Watchmen chapter 2, page 4, panels 5-6 (ISBN 0930289234)

- ^ "The Annotated Watchmen: Your complete guide to the classic series" — Chapter 1: "At Midnight, All the Agents...", p. 1, panel 4. (retrieved 5 June 2006)

- ^ "Watchmen by Alan Moore" — Celinus (retrieved 5 June 2006)

- ^ "Narcissistic Personality Disorder" — Behavenet Clinical Capsule (retrieved 5 June 2006)

- ^ "PopImage" - retrieved (22 April 2006)

- ^ "Don Markstein's Toonopedia: Watchmen" — Markstein's Comments on Toonopedia.com - (retrieved 12 March 2006)

- ^ a b "RevolutionSF: Watchmen — A review of Watchmen (retrieved 14 April 2006)

- ^ "Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons: Watchmen". Bob's Comic Reviews. zompist.com. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Shone, Tom (2005-11-30). "Fighting Evil, Quoting Nietzsche: Did the comic book really need to grow up?". Slate. Retrieved 2006-04-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "THE INCREDIBLES (WIDESCREEN 2-DISC COLLECTOR'S EDITION) (2004)". Scifi Movie Page. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "Film Rotation - Update: Watchmen" - retrieved 22 April 2006

- ^ "The Annotated Watchmen" - information regarding Mayfair Games' release of Watchmen' related material.

- ^ "PeterDavid.net" - a personal blog entry where fans discuss Alan Moore

- ^ "Comics Continuum" DC Comics statement regarding Alan Moore's refusal to be involved with their proposed line of action figures - (retrieved 15 April 2006).

- ^ "Alan Moore: The Last Angry Man" - Interview with Moore for MTV.com that covers his views of adapting Watchmen into a film (retrieved August 23 2006

- ^ "Interview with Terry Gilliam" - Interview with Terry Gilliam by Kenneth Plume (retrieved August 23 2006

- ^ "Watchmen: An Oral History" - Provides commentary from Moore, Gibbons and others regarding the comic and film (retrieved May 28 2006)

- ^ "Moore Leaves DC for Top Shelf" - An article speaking of Alan Moore's decision to leave DC Comics (retrieved 15 April 2006)

- ^ Borys Kit (June 23, 2006). "Zack Snyder attached to direct Watchmen". Hollywood Reporter. Reuters.

External links

- Ralf Hildebrandt's Annotations

- Doug Atkinson's Annotations

- Samuel Effron's Analysis

- Spanish article about the comic, its authors and its repercussions

- Alan Moore Interview

- Watching the Detectives: An Internet Companion for Readers of Watchmen

- Watchmen at IMDb

- Tales Of The Black Freighter: "Marooned" (The Reconstruction), an attempt to recreate the comic as it may have looked.

- Original Alan Moore Interview regarding his decision to leave DC Comics for Top Shelf.