Chondrichthyes: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 71.224.108.48 identified as vandalism to last revision by 12.214.32.40. (TW) |

Isaidnoway (talk | contribs) Undid edit by 173.196.189.82 (talk) — reverting unexplained partial removal of reference that then created a citation error, clean up pages with incorrect ref formatting |

||

| (791 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Class of jawed cartilaginous fishes}} |

|||

{{Taxobox |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2020}} |

|||

| name = Cartilaginous fish<nowiki>es</nowiki> |

|||

{{Automatic taxobox |

|||

| fossil_range = Early [[Silurian]] - Recent |

|||

| name = Cartilaginous fishes |

|||

| image = White shark.jpg |

|||

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|439|0}} Early [[Silurian]] ([[Aeronian]]) - Present |

|||

| image_width = 250px |

|||

| image = Chondrichthyes.jpg |

|||

| image_caption = [[Great white shark]], ''Carcharodon carcharias'' |

|||

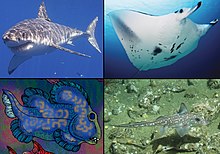

| image_caption = Example of cartilaginous fishes: [[Elasmobranchii]] at the top of the image and [[Holocephali]] at the bottom of the image. |

|||

| regnum = [[Animalia]] |

|||

| display_parents = 3 |

|||

| phylum = [[Chordata]] |

|||

| taxon = Chondrichthyes |

|||

| subphylum = |

|||

| authority = [[Thomas Henry Huxley|Huxley]], 1880 |

|||

| infraphylum = [[Gnathostomata]] |

|||

| subdivision_ranks = Living subclasses and orders |

|||

| classis = '''Chondrichthyes''' |

|||

| subdivision = * Subclass [[Elasmobranchii]] |

|||

| classis_authority = [[Thomas Henry Huxley|Huxley]], 1880 |

|||

** Superorder [[Selachimorpha]] |

|||

| subdivision_ranks = [[Subclass]]es and [[Orders (biology)|Orders]] |

|||

*** Order [[Carcharhiniformes]] |

|||

| subdivision = |

|||

*** Order [[Lamniformes]] |

|||

See text. |

|||

*** Order [[Orectolobiformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Heterodontiformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Squaliformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Squatiniformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Pristiophoriformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Hexanchiformes]] |

|||

** Superorder [[Batoidea]] |

|||

*** Order [[Myliobatiformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Rajiformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Rhinopristiformes]] |

|||

*** Order [[Torpediniformes]] |

|||

* Subclass [[Holocephali]] |

|||

** Superorder [[Holocephalimorpha]] |

|||

*** Order [[Chimaeriformes]] |

|||

* ''[[Incertae sedis]]'' |

|||

**†''[[Bandringa]]''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Mazon Monday #19: Species Spotlight: Bandringa rayi #MazonCreek #fossils #MazonMonday #shark |url=https://www.esconi.org/esconi_earth_science_club/2020/08/mazon-monday-19-species-spotlight-bandringa-rayi-mazoncreek-fossils-mazonmonday-shark.html |access-date=2020-10-04 |website=Earth Science Club of Northern Illinois - ESCONI}}</ref> |

|||

**†''[[Delphyodontos]]''<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://people.sju.edu/~egrogan/BearGulch/pages_fish_species/Delphyodontos_dacriformes.html|title=Bear Gulch - Delphyodontos dacriformes|work=Fossil Fishes of Bear Gulch|access-date=2019-05-15|archive-date=25 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150225041927/http://people.sju.edu/~egrogan/BearGulch/pages_fish_species/Delphyodontos_dacriformes.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

**†[[Listracanthidae]]<ref name="mutter2006">{{cite journal | first1 = R.J. | last1 = Mutter | first2 = A.G. | last2 = Neuman | title = An enigmatic chondrichthyan with Paleozoic affinities from the Lower Triassic of western Canada | journal = Acta Palaeontologica Polonica | volume = 51 | issue = 2 | pages = 271–282 | url = https://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app51-271.html}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Fossilworks: Acanthorhachis|url=http://www.fossilworks.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=289828|access-date=17 December 2021|website=fossilworks.org}}</ref> |

|||

** †[[Mcmurdodontidae]]<ref>{{Citation |last1=Long |first1=John |title=Fossil chondrichthyan remains from the Middle Devonian Kevington Creek Formation, South Blue Range, Victoria |date=2021-10-28 |url=https://researchnow-admin.flinders.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/48435020/Long_et_al_2021_MId_dev_sharks_Victoria_JOHN_MAISEY_VOLUME.pdf|work=Ancient Fishes and their Living Relatives |pages=239–245 |editor-last=Pradel |editor-first=Alan |access-date=2023-11-30 |place=Munich, Germany |publisher=Verlag, Dr Friedrich Pfeil |isbn=978-3-89937-269-4 |last2=Thomson |first2=Victoria |last3=Burrow |first3=Carole |last4=Turner |first4=Susan |editor2-last=Denton |editor2-first=John S.S. |editor3-last=Janvier |editor3-first=Philippe}}</ref> |

|||

** †''[[Nanocetorhinus]]''<ref name=UnderwoodetSchlogl>{{cite journal |author=Charlie J. Underwood and Jan Schlogl |year=2012 |title=Deep water chondrichthyans from the Early Miocene of the Vienna Basin (Central Paratethys, Slovakia) |journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica |volume=58 |issue=3 |pages=487–509 |url=http://app.pan.pl/article/item/app20110101.html |doi=10.4202/app.2011.0101|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

** †''[[Plesioselachus]]''<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |last1=Anderson |first1=M. Eric |last2=Long |first2=John A. |last3=Gess |first3=Robert W. |last4=Hiller |first4=Norton |year=1999 |title=An unusual new fossil shark (Pisces: Chondrichthyes) from the Late Devonian of South Africa |url=http://museum.wa.gov.au/research/records-supplements/records/unusual-new-fossil-shark-pisces-chondrichthyes-late-devonian-so |journal=Records of the Western Australian Museum |volume=57 |pages=151–156}}</ref> |

|||

** †[[Psammodontiformes]] |

|||

** †''[[Xiphodolamia]]''<ref name="adnet2009">{{Cite journal|last1=Adnet|first1=S.|last2=Hosseinzadeh|first2=R.|last3=Antunes|first3=M. T.|last4=Balbino|first4=A. C.|last5=Kozlov|first5=V. A.|last6=Cappetta|first6=H.|date=2009-10-01|title=Review of the enigmatic Eocene shark genus Xiphodolamia (Chondrichthyes, Lamniformes) and description of a new species recovered from Angola, Iran and Jordan|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1464343X09000752|journal=Journal of African Earth Sciences|language=en|volume=55|issue=3|pages=197–204|doi=10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2009.04.005|bibcode=2009JAfES..55..197A |issn=1464-343X}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Chondrichthyes or '''cartilaginous fishes''' are jawed [[fish]] with paired fins, paired nostrils, scales, two-chambered hearts, and skeletons made of [[cartilage]] rather than [[bone]]. They are divided into two subclasses: [[Elasmobranchii]] (sharks, rays and skates) and Holocephali ([[chimaera]], sometimes called ghost sharks). |

|||

'''Chondrichthyes''' ({{IPAc-en|k|ɒ|n|ˈ|d|r|ɪ|k|θ|i|.|iː|z}}; {{etymology|grc|''{{wikt-lang|grc|χόνδρος}}'' (khóndros)|cartilage||''{{wikt-lang|grc|ἰχθύς}}'' (ikhthús)|fish}}) is a [[class (biology)|class]] of [[jawed fish]] that contains the '''cartilaginous fish''' or '''chondrichthyians''', which all have [[skeleton]]s primarily composed of [[cartilage]]. They can be contrasted with the [[Osteichthyes]] or ''bony fish'', which have skeletons primarily composed of [[bone tissue]]. Chondrichthyes are [[aquatic animal|aquatic]] [[vertebrate]]s with [[paired fins]], paired [[nare]]s, [[placoid scale]]s, [[conus arteriosus]] in the [[heart]], and a lack of [[operculum (fish)|opecula]] and [[swim bladder]]s. Within the infraphylum [[Gnathostomata]], cartilaginous fishes are distinct from all other jawed vertebrates. |

|||

== Characteristics == |

|||

Animals from this group have a brain weight relative to body size that comes close to that of mammals, and is about 10 times that of [[Osteichthyes|bony fishes]]. There are exceptions: the [[mormyrid]] bony fish have a relative brain size comparable to humans, while the primitive [[megamouth shark]] has a brain of only 0.002 percent of its body weight. One of the explanations for their relatively large brains is that the density of nerve cells is much lower than in the brains of bony fishes, making the brain less energy demanding and allowing it to be bigger. Extant cartilaginous fishes range in size from the [[Dwarf lanternshark]], at 16 cm (6.3 in), to the [[Whale Shark]], growing to at least 13.6 m (45 feet). |

|||

The class is divided into two subclasses: [[Elasmobranchii]] ([[shark]]s, [[Batoidea|ray]]s, [[skate (fish)|skate]]s and [[sawfish]]) and [[Holocephali]] ([[chimaera]]s, sometimes called ghost sharks, which are sometimes separated into their own class). Extant Chondrichthyes range in size from the {{cvt|10|cm}} [[finless sleeper ray]] to the over {{cvt|10|m}} [[whale shark]]. |

|||

Their digestive systems have [[spiral valve]]s, and with the exception of Holocephali, they also have a [[cloaca]]. |

|||

==Anatomy== |

|||

As they do not have bone [[marrow]], [[red blood cell]]s are produced in the [[spleen]] and special tissue around the [[gonad]]s. They are also produced in an organ called [[Leydig's Organ]] which is only found in cartilaginous fishes, although some have lost it. Another unique organ is the epigonal organ which probably has a role in the immune system. The subclass Holocephali, which is a very specialized group, lacks both of these organs. Originally the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which do not contain any dermal elements, did not connect. In later forms, each pair of fins became ventrally connected in the middle when scapulocoracoid and pubioischiadic bars evolved. In [[Batoidea|ray]]s, the pectoral fins have connected to the head and are very flexible. |

|||

{{See also|Cartilaginous versus bony fishes}} |

|||

===Skeleton=== |

|||

A [[spiracle]] is found behind each eye on most species. |

|||

The skeleton is cartilaginous. The [[notochord]] is gradually replaced by a vertebral column during development, except in [[Holocephali]], where the notochord stays intact. In some deepwater sharks, the column is reduced.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cxxSN4YA2i8C&dq=Notochord:+Chimaeroids+%22Some+deepwater+squaloid,+hexanchoid,+and+lamnoid+sharks+%22&pg=PA23|title=Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date|first1=Leonard J. V.|last1=Compagno|first2=Food and Agriculture Organization of the United|last2=Nations|date=20 November 2001|publisher=Food & Agriculture Org.|isbn=9789251045435 |via=Google Books}}</ref> |

|||

As they do not have [[bone marrow]], [[red blood cell]]s are produced in the [[spleen]] and the epigonal organ (special tissue around the [[gonad]]s, which is also thought to play a role in the immune system). They are also produced in the [[Leydig's organ]], which is only found in certain cartilaginous fishes. The subclass [[Holocephali]], which is a very specialized group, lacks both the Leydig's and epigonal organs. |

|||

Their tough skin is covered with [[Denticle|dermal teeth]] (again with Holocephali as an exception as the teeth are lost in adults, only kept on the clasping organ seen on the front of the male's head), also called placoid scales or [[dermal denticle]]s, making it feel like sandpaper. It is assumed that their oral teeth evolved from dermal denticles which migrated into the mouth. But it could be the other way around as the [[Teleostei|teleost]] bony fish ''[[Denticeps clupeoides]]'' has most of its head covered by dermal teeth (as do probably ''[[Atherion elymus]]'', another bony fish). This is most probably a secondary evolved characteristic which means there is not necessarily a connection between the teeth and the original dermal scales. The old [[placoderms]] did not have teeth at all, but had sharp bony plates in their mouth. Thus, it is unknown which of the dermal or oral teeth evolved first. Neither is it sure how many times it has happened if it turns out to be the case. It has even been suggested that the original bony plates of all the vertebrates are gone and that the present scales are just modified teeth, even if both teeth and the body armour have a common origin a long time ago. But for the moment there is no evidence of this. |

|||

===Appendages=== |

|||

==Respiratory system== |

|||

Apart from [[electric ray]]s, which have a thick and flabby body, with soft, loose skin, chondrichthyans have tough skin covered with dermal teeth (again, Holocephali is an exception, as the teeth are lost in adults, only kept on the clasping organ seen on the caudal ventral surface of the male), also called [[placoid scale]]s (or ''dermal denticles''), making it feel like sandpaper. In most species, all dermal denticles are oriented in one direction, making the skin feel very smooth if rubbed in one direction and very rough if rubbed in the other. |

|||

Chondrichthyes all breathe through [[gills]]. However, they differ on how they get water to pass over the gills. Sharks mostly use their throat, as do chimaeras and skates, but rays get water through [[spiracles]]. |

|||

Originally, the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which do not contain any dermal elements, did not connect. In later forms, each pair of fins became ventrally connected in the middle when scapulocoracoid and puboischiadic bars evolved. In [[Batoidea|rays]], the pectoral fins are connected to the head and are very flexible. |

|||

==Metabolism== |

|||

Chondrichthyes are [[ectothermic]] or cold blooded, meaning they do not have to warm themselves through eating. Therefore, metabolism is slow as well as the fact that Chondrichthyes members do not have to eat as much. They have no stomach. |

|||

One of the primary characteristics present in most sharks is the heterocercal tail, which aids in locomotion.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=C. D. |last1=Wilga |first2=G. V. |last2=Lauder |title=Function of the heterocercal tail in sharks: quantitative wake dynamics during steady horizontal swimming and vertical maneuvering |journal=[[Journal of Experimental Biology]] |volume=205 |issue=16 |pages=2365–2374 |year=2002 |doi=10.1242/jeb.205.16.2365 |url=http://jeb.biologists.org/content/205/16/2365.short |pmid=12124362}}</ref> |

|||

==Body covering== |

|||

Chondrichthyes have toothlike scales called [[denticles]/placoid scales. Mucous glands exist as well. |

|||

== |

===Body covering=== |

||

Chondrichthyans have tooth-like scales called [[dermal denticle]]s or placoid scales. Denticles usually provide protection, and in most cases, streamlining. Mucous glands exist in some species, as well. |

|||

Chondrichthyes have paired fins and paired nostrils. |

|||

It is assumed that their oral teeth evolved from dermal denticles that migrated into the mouth, but it could be the other way around, as the [[Teleostei|teleost]] bony fish ''[[Denticeps clupeoides]]'' has most of its head covered by dermal teeth (as does, probably, ''[[Atherion elymus]]'', another bony fish). This is most likely a secondary evolved characteristic, which means there is not necessarily a connection between the teeth and the original dermal scales. |

|||

==Skeleton== |

|||

The skeleton is cartilaginous. The [[notochord]], which is present in the young, is gradually replaced by cartilage. |

|||

The old [[placoderms]] did not have teeth at all, but had sharp bony plates in their mouth. Thus, it is unknown whether the dermal or oral teeth evolved first. It has even been suggested{{by whom|date=August 2018}} that the original bony plates of ''all'' vertebrates are now gone and that the present scales are just modified teeth, even if both the teeth and body armor had a common origin a long time ago. However, there is currently no evidence of this. |

|||

===Respiratory system=== |

|||

All chondrichthyans breathe through five to seven pairs of [[gill]]s, depending on the species. In general, pelagic species must keep swimming to keep oxygenated water moving through their gills, whilst demersal species can actively pump water in through their [[Spiracle (vertebrates)|spiracles]] and out through their gills. However, this is only a general rule and many species differ. |

|||

A spiracle is a small hole found behind each eye. These can be tiny and circular, such as found on the nurse shark (''Ginglymostoma cirratum''), to extended and slit-like, such as found on the wobbegongs (Orectolobidae). Many larger, pelagic species, such as the mackerel sharks (Lamnidae) and the thresher sharks (Alopiidae), no longer possess them. |

|||

===Nervous system=== |

|||

[[File:Skate Brain Regions.png|thumb|Regions of a Chondrichthyes brain colored and labeled on dissected skate. The [[Anatomical terms of location#Cranial and caudal|rostral]] end of the skate is to the right.]] |

|||

In chondrichthyans, the nervous system is composed of a small brain, 8–10 pairs of cranial nerves, and a spinal cord with spinal nerves.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Collin|first=Shaun P.|date=2012|title=The Neuroecology of Cartilaginous Fishes: Sensory Strategies for Survival|journal=Brain, Behavior and Evolution|language=en|volume=80|issue=2|pages=80–96|doi=10.1159/000339870|pmid=22986825|s2cid=207717002|issn=1421-9743}}</ref> They have several sensory organs which provide information to be processed. [[Ampullae of Lorenzini]] are a network of small jelly filled pores called [[Electroreception|electroreceptors]] which help the fish sense electric fields in water. This aids in finding prey, navigation, and sensing temperature. The [[Lateral line]] system has modified epithelial cells located externally which sense motion, vibration, and pressure in the water around them. Most species have large well-developed eyes. Also, they have very powerful nostrils and [[Olfactory bulb|olfactory]] organs. Their inner ears consist of 3 large [[semicircular canals]] which aid in balance and orientation. Their sound detecting apparatus has limited range and is typically more powerful at lower frequencies. Some species have [[Electric organ (biology)|electric organs]] which can be used for defense and predation. They have relatively simple brains with the forebrain not greatly enlarged. The structure and formation of myelin in their nervous systems are nearly identical to that of tetrapods, which has led evolutionary biologists to believe that Chondrichthyes were a cornerstone group in the evolutionary timeline of myelin development.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=de Bellard|first=Maria Elena|date=2016-06-15|title=Myelin in cartilaginous fish|journal=Brain Research|volume=1641|issue=Pt A|pages=34–42|doi=10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.013|issn=0006-8993|pmc=4909530|pmid=26776480}}</ref> |

|||

===Immune system=== |

|||

Like all other jawed vertebrates, members of Chondrichthyes have an [[adaptive immune system#Evolution|adaptive immune system]].<ref name=ref1>{{cite journal |last1=Flajnik |first1=M. F. |first2=M. |last2=Kasahara |title=Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: genetic events and selective pressures |journal=[[Nature Reviews Genetics]] |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=47–59 |year=2009 |doi=10.1038/nrg2703 |pmid=19997068 |pmc=3805090}}</ref> |

|||

==Reproduction== |

==Reproduction== |

||

Fertilization is internal. Development is usually live birth ([[ovoviviparous]] species) but can be through eggs ([[oviparous]]). Some rare species are [[viviparous]]. There is no parental care after birth, however, some Chondrichthyes do guard their eggs. |

|||

Fertilization is internal. Development is usually live birth ([[ovoviviparous]] species) but can be through eggs ([[oviparous]]). Some rare species are [[viviparous]]. There is no parental care after birth; however, some chondrichthyans do guard their eggs. |

|||

==Members== |

|||

*[[Chimaeras]] |

|||

*[[Sharks]] |

|||

*[[Skates]] |

|||

*[[Rays]] |

|||

Capture-induced premature birth and abortion (collectively called capture-induced parturition) occurs frequently in sharks/rays when fished.<ref name="Adams">{{cite journal|last1=Adams|first1=Kye R.|last2=Fetterplace|first2=Lachlan C.|last3=Davis|first3=Andrew R.|last4=Taylor|first4=Matthew D.|last5=Knott|first5=Nathan A.|title=Sharks, rays and abortion: The prevalence of capture-induced parturition in elasmobranchs|journal=Biological Conservation|date=January 2018|volume=217|pages=11–27|doi=10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.010|s2cid=90834034 |url=http://marxiv.org/k2qvy/|access-date=18 January 2019|archive-date=23 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190223020619/https://marxiv.org/k2qvy/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Capture-induced parturition is often mistaken for natural birth by recreational fishers and is rarely considered in commercial fisheries management despite being shown to occur in at least 12% of live bearing sharks and rays (88 species to date).<ref name="Adams" /> |

|||

== Taxonomy == |

|||

* Class '''Chondrichthyes''' |

|||

** Subclass [[Elasmobranchii]] (sharks, rays and skates) |

|||

*** Superorder [[Batoidea]] (rays and skates), containing the orders: |

|||

***# [[Rajiformes]] (common rays and skates) |

|||

***# [[Pristiformes]] ([[Sawfish (fish)|Sawfishes]]) |

|||

***# [[Torpediniformes]] ([[electric ray]]s) |

|||

*** Superorder [[Selachimorpha]] ([[shark]]s), containing the orders: |

|||

***# [[Hexanchiformes]] Two families are found within this order. Species of this order are distinguished from other sharks by having additional gill slits (either six or seven). Examples from this group include the [[cow shark]]s, [[frilled shark]] and even a shark that looks on first inspection to be a marine snake. |

|||

***# [[Squaliformes]] Three families and more than 80 species are found within this order. These sharks have two dorsal fins, often with spines, and no anal fin. They have teeth designed for cutting in both the upper and lower jaws. Examples from this group include the [[bramble shark]]s, [[dogfish]] and [[roughshark]]s. |

|||

***# [[Pristiophoriformes]] One family is found within this order. These are the ''sawsharks'', with an elongate, toothed snout that they use for slashing the fishes that they then eat. |

|||

***# [[Squatiniformes]] One family is found within this order. These are flattened sharks that can be distinguished from the similar appearing skates and rays by the fact that they have the gill slits along the side of the head like all other sharks. They have a caudal fin (tail) with the lower lobe being much longer in length than the upper, and are commonly referred to as ''angel sharks''. |

|||

***# [[Heterodontiformes]] One family is found within this order. They are commonly referred to as the ''bullhead'', or ''horn sharks''. They have a variety of teeth allowing them to grasp and then crush [[shellfish]]es. |

|||

***# [[Orectolobiformes]] Seven families are found within this order. They are commonly referred to as the ''carpet sharks'', including [[zebra shark]]s, [[nurse sharks]], [[wobbegong]]s and the largest of all fishes, the [[whale shark]]s. They are distinguished by having [[barbels]] at the edge of the nostrils. Most, but not all are nocturnal. These things rock. |

|||

***# [[Carcharhiniformes]] Eight families are found within this order. It is the largest order, containing almost 200 species. They are commonly referred to as the ''groundsharks'', and some of the species include the [[blue shark|blue]], [[tiger shark|tiger]], [[bull shark|bull]], [[reef shark|reef]] and [[oceanic whitetip shark]]s (collectively called the [[requiem shark]]s) along with the [[houndshark]]s, [[catshark]]s and [[hammerhead shark]]s. They are distinguished by an elongated snout and a nictitating membrane which protects the eyes during an attack. |

|||

***# [[Lamniformes]] Seven families are found within this order. They are commonly referred to as the ''mackerel sharks''. They include the [[goblin shark]], [[basking shark]], [[megamouth]], the [[Thresher Shark|thresher]], [[mako shark]] and [[great white shark]]. They are distinguished by their large jaws and [[Ovoviviparity|ovoviviparous]] reproduction. The Lamniformes contains the extinct [[Megalodon]] (''Carcharodon megalodon''), which like most extinct sharks is only known by the teeth (the only bone found in these cartilaginous fishes, and therefore are often the only [[fossil]]s produced) and a few [[vertebrae]]. The largest of the teeth of this shark can measure (up to more than 7 inch in length) and through modern research, it has been determined that this shark could exceed 50 feet in length. |

|||

==Classification== |

|||

** Subclass [[Holocephali]] ([[chimaera]]) |

|||

The class Chondrichthyes has two subclasses: the subclass [[Elasmobranchii]] ([[shark]]s, [[Batoidea|rays, skates, and sawfish]]) and the subclass [[Holocephali]] ([[chimaera]]s). To see the [[full list of cartilaginous fish|full list of the species]], click [[full list of cartilaginous fish|here]]. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=3 | [[Subclass (biology)|Subclasses]] of cartilaginous fishes |

|||

|- |

|||

! [[Elasmobranchii]] |

|||

| <span style="{{MirrorH}}">[[File:White shark (Duane Raver).png|140px]]</span>{{center|[[Sharks]]}} |

|||

[[File:Myliobatis aquila sasrája.jpg|140px|right]]{{center|and [[Batoidea|rays, skates, and sawfish]]}} |

|||

| valign=top | [[Elasmobranchii]] is a subclass that includes the [[shark]]s and the [[Batoidea|rays and skates]]. Members of the elasmobranchii have no [[swim bladders]], five to seven pairs of [[gill]] clefts opening individually to the exterior, rigid [[dorsal fins]], and small [[placoid scale]]s. The teeth are in several series; the upper jaw is not fused to the cranium, and the lower jaw is articulated with the upper. The [[Vision in fishes|eyes]] have a [[tapetum lucidum]]. The inner margin of each pelvic fin in the male fish is grooved to constitute a [[clasper]] for the transmission of [[sperm]]. These fish are widely distributed in [[tropical]] and [[temperate]] waters.<ref>{{cite book | |

|||

last = Bigelow| first = Henry B. | |

|||

authorlink = Henry Bryant Bigelow|author2=Schroeder, William C. | |

|||

title = Fishes of the Western North Atlantic | |

|||

publisher = Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University | |

|||

year = 1948 | |

|||

pages = 64–65 | |

|||

asin= B000J0D9X6| author-link2 = Schroeder, William C }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! [[Holocephali]] |

|||

| [[File:Chimaera monstrosa1.jpg|140px]]{{center|[[Chimaeras]]}} |

|||

| [[Holocephali]] ''(complete-heads)'' is a subclass of which the [[order (biology)|order]] [[Chimaeriformes]] is the only surviving group. This group includes the rat fishes (e.g., ''[[Chimaera]]''), rabbit-fishes (e.g., ''[[Hydrolagus]]'') and elephant-fishes (''[[Callorhynchus]]''). Today, they preserve some features of elasmobranch life in Paleaozoic times, though in other respects they are aberrant. They live close to the bottom and feed on molluscs and other invertebrates. The tail is long and thin and they move by sweeping movements of the large pectoral fins. There is an erectile spine in front of the dorsal fin, sometimes poisonous. There is no stomach (that is, the gut is simplified and the 'stomach' is merged with the intestine), and the mouth is a small aperture surrounded by lips, giving the head a parrot-like appearance. |

|||

The fossil record of the Holocephali starts in the [[Devonian]] period. The record is extensive, but most fossils are teeth, and the body forms of numerous species are not known, or at best poorly understood. |

|||

|} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=13 | Extant [[Order (biology)|orders]] of cartilaginous fishes |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Group |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Order |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Image |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Common name |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Authority |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Families |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Genera |

|||

! colspan=4 | Species |

|||

! rowspan=2 | Note |

|||

|- |

|||

! Total |

|||

! [[File:CR IUCN 3 1.svg]] |

|||

! [[File:EN IUCN 3 1.svg]] |

|||

! [[File:VU IUCN 3 1.svg]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(110,110,170)" rowspan=4 | [[Galean shark|<span style="color:white;">Galean<br />sharks</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Carcharhiniformes|<span style="color:white;">Carcharhiniformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Sphyrna mokarran at georgia.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[ground sharks|ground<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Leonard Compagno|Compagno]], 1977</small> |

|||

| align=center | 8 |

|||

| align=center | 51 |

|||

| align=center | >270 |

|||

| align=center | 7 |

|||

| align=center | 10 |

|||

| align=center | 21 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Heterodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">Heterodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Hornhai (Heterodontus francisci).JPG|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[bullhead sharks|bullhead<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Lev Berg|L. S. Berg]], 1940</small> |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 9 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Lamniformes|<span style="color:white;">Lamniformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:White shark.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[mackerel sharks|mackerel<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Lev Berg|L. S. Berg]], 1958</small> |

|||

| align=center | 7<br /><small>+2 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | 10 |

|||

| align=center | 16 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | 10 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Orectolobiformes|<span style="color:white;">Orectolobiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Whale shark Georgia aquarium.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[carpet sharks|carpet<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>Applegate, 1972</small> |

|||

| align=center | 7 |

|||

| align=center | 13 |

|||

| align=center | 43 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | 7 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(110,110,170)" rowspan=4 | [[Squalomorphii|<span style="color:white;">Squalomorph<br />sharks</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Hexanchiformes|<span style="color:white;">Hexanchiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Hexanchus griseus Gervais.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Hexanchiformes|frilled<br />and<br />cow sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Don Fernando de Buen y Lozano|de Buen]], 1926</small> |

|||

| align=center | 2<br /><small>+3 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | 4<br /><small>+11 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | 7<br /><small>+33 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Pristiophoriformes|<span style="color:white;">Pristiophoriformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Pristiophorus japonicus cropped.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[sawsharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Lev Berg|L. S. Berg]], 1958</small> |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | 6 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Squaliformes|<span style="color:white;">Squaliformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Spiny dogfish.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[dogfish sharks|dogfish<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Edwin Stephen Goodrich|Goodrich]], 1909</small> |

|||

| align=center | 7 |

|||

| align=center | 23 |

|||

| align=center | 126 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | 6 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Squatiniformes|<span style="color:white;">Squatiniformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Squatina angelus - Gervais.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[angel sharks|angel<br />sharks]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Don Fernando de Buen y Lozano|Buen]], 1926</small> |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 24 |

|||

| align=center | 3 |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | 5 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(110,110,170)" rowspan=4 | [[Batoidea|<span style="color:white;">Rays</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Myliobatiformes|<span style="color:white;">Myliobatiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Myliobatis aquila sasrája.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Myliobatiformes|stingrays<br />and<br />relatives]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Leonard Joseph Victor Compagno|Compagno]], 1973</small> |

|||

| align=center | 10 |

|||

| align=center | 29 |

|||

| align=center | 223 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 16 |

|||

| align=center | 33 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Rhinopristiformes|<span style="color:white;">Rhinopristiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Sawfish genova.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[sawfishes]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | 5–7 |

|||

| align=center | 5–7 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Rajiformes|<span style="color:white;">Rajiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Amblyraja hyperborea1.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Rajiformes|skates<br />and<br />guitarfishes]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Lev Berg|L. S. Berg]], 1940</small> |

|||

| align=center | 5 |

|||

| align=center | 36 |

|||

| align=center | >270 |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | 12 |

|||

| align=center | 26 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(125,125,180)" | [[Torpediniformes|<span style="color:white;">Torpediniformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Torpedo torpedo corsica2.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[electric rays|electric<br />rays]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Don Fernando de Buen y Lozano|de Buen]], 1926</small> |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | 12 |

|||

| align=center | 69 |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | 9 |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(110,110,170)" rowspan=1 | [[Holocephali|<span style="color:white;">Holocephali</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(140,140,190)" | [[Chimaeriformes|<span style="color:white;">Chimaeriformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Chimaera mon.JPG|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[chimaera]] |

|||

| align=center | <small>[[Dmitry Obruchev|Obruchev]], 1953</small> |

|||

| align=center | 3<br /><small>+2 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | 6<br /><small>+3 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | 39<br /><small>+17 extinct</small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|} |

|||

{| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" |

|||

! width=450px | Taxonomy according to [[Leonard Compagno]], 2005<ref>{{cite book|publisher = Princeton University Press|author1-link =Leonard Compagno|first1= Leonard|last1 = Compagno|first2= Marc |last2 =Dando|first3= Sarah L.|last3 = Fowler |date = 2005|title =Sharks of the World|isbn = 9780691120720}}</ref> with additions from <ref>{{cite book|last=Haaramo, Mikko|title=''Chondrichthyes – Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras'' |access-date=22 October 2013 | url=http://www.helsinki.fi/~mhaaramo/metazoa/deuterostoma/chordata/chondrichthyes/chondrichthyes.html#Elasmobranchii}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

*†Order [[Mongolepidiformes]] <small>Karatajüte-Talimaa & Novitskaya, 1990</small> |

|||

*†Order [[Omalodontiformes]] <small>Turner, 1997</small> |

|||

*†Order [[Coronodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

*†Order [[Symmoriiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

*Subclass [[Holocephali]] |

|||

**†Superorder Paraselachimorpha |

|||

***†Order [[Desmiodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Polysentoriformes]] <small>Cappetta, 1993</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Orodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Petalodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Helodontiformes]] <small>Patterson, 1965</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Iniopterygiformes]] <small>Zanger, 1973</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Debeeriiformes]] <small>Grogan & Lund, 2000</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Eugeneodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

**Superorder Holocephalimorpha <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Psammodontiformes]]* <small>Obruchev, 1953</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Copodontiformes]] <small>Obručhev, 1953</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Squalorajiformes]] <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Chondrenchelyiformes]] <small>[[J. A. Moy-Thomas|Moy-Thomas]], 1939</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Menaspiformes]] <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Cochliodontiformes]] <small>Obručhev, 1953</small> |

|||

***Order [[Chimaeriformes]] <small>Berg, 1940 sensu Obručhev, 1953</small> (chimaeras) |

|||

*Subclass [[Elasmobranchii]] |

|||

**†''[[Plesioselachus]]'' <small></small> |

|||

**†Order [[Antarctilamniformes]] <small>Ginter, Liao & Valenzuela-Rios, 2008</small> |

|||

**†Order [[Elegestolepidiformes]] <small>Andreev ''et al.'', 2016</small> |

|||

**†Order [[Lugalepidida]] <small>Karatajute-Talimaa, 1997</small> |

|||

**†Order [[Squatinactiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

**†Order [[Protacrodontiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

**†Infraclass Cladoselachimorpha <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Cladoselachiformes]] <small>Dean, 1909</small> |

|||

**†Infraclass Xenacanthimorpha <small>Berg, 1940</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Bransonelliformes]] <small>Hampe & Ivanov, 2007</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Xenacanthiformes]] <small>Berg, 1940</small> |

|||

**Infraclass Euselachii (sharks and rays) |

|||

***†Order [[Altholepidiformes]] <small>Andreev ''et al.'', 2015</small> |

|||

***†Order [[Polymerolepidiformes]] <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Ptychodontiformes]] <small></small> |

|||

***†Order [[Ctenacanthiformes]] <small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

***†Division Hybodonta |

|||

****†Order [[Hybodontiformes]] <small>Owen, 1846</small> |

|||

***Division Neoselachii <small>Compagno, 1977</small> |

|||

****Subdivision Selachii (modern sharks) |

|||

*****Superorder Galeomorphi <small>Compagno, 1977</small> |

|||

******Order [[Heterodontiformes]] (bullhead sharks) |

|||

******Order [[Orectolobiformes]] (carpet sharks) |

|||

******Order [[Lamniformes]] (mackerel sharks) |

|||

******Order [[Carcharhiniformes]] (ground sharks) |

|||

*****Superorder Squalomorphi |

|||

******Order [[Chlamydoselachiformes]] |

|||

******Order [[Hexanchiformes]] (frilled and cow sharks) |

|||

******Order [[Squaliformes]] (dogfish sharks) |

|||

******†Order [[Protospinaciformes]] |

|||

******†Order [[Synechodontiformes]] |

|||

******Order [[Squatiniformes]] (angel sharks) |

|||

******Order [[Pristiophoriformes]] (sawsharks) |

|||

****Subdivision Batoidea |

|||

*****Order [[Torpediniformes]] (electric rays) |

|||

*****Order [[Pristiformes]] (sawfishes) |

|||

*****Order [[Rajiformes]] (skates and guitarfishes) |

|||

*****Order [[Myliobatiformes]] (stingrays and relatives) |

|||

<small>* position uncertain</small> |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

==Evolution== |

|||

{{See also|Evolution of fish}} |

|||

{{Further|List of transitional fossils#Chondrichthyes|List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish}} |

|||

Cartilaginous fish are considered to have evolved from [[acanthodians]]. The discovery of ''[[Entelognathus]]'' and several examinations of acanthodian characteristics indicate that bony fish evolved directly from placoderm like ancestors, while acanthodians represent a paraphyletic assemblage leading to Chondrichthyes. Some characteristics previously thought to be exclusive to acanthodians are also present in basal cartilaginous fish.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Min Zhu |author2=Xiaobo Yu |author3=Per Erik Ahlberg |author4=Brian Choo |author5=Jing Lu |author6=Tuo Qiao |author7=Qingming Qu |author8=Wenjin Zhao |author9=Liantao Jia |author10=Henning Blom |author11=You'an Zhu |year=2013 |title=A Silurian placoderm with osteichthyan-like marginal jaw bones |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=502 |issue=7470 |pages=188–193 |doi=10.1038/nature12617 |pmid=24067611|bibcode=2013Natur.502..188Z |s2cid=4462506 }}</ref> In particular, new phylogenetic studies find cartilaginous fish to be well nested among acanthodians, with ''[[Doliodus]]'' and ''[[Tamiobatis]]'' being the closest relatives to Chondrichthyes.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.26879/601|title=The diplacanthid fishes (Acanthodii, Diplacanthiformes, Diplacanthidae) from the Middle Devonian of Scotland|journal=Palaeontologia Electronica|year=2016|last1=Burrow|first1=CJ|last2=Den Blaauwen|first2=J.|last3=Newman|first3=MJ|last4=Davidson|first4=RG|doi-access=free}}</ref> Recent studies vindicate this, as ''[[Doliodus]]'' had a mosaic of chondrichthyan and acanthodian traits.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1206/3875.1|title=Pectoral Morphology in ''Doliodus'': Bridging the 'Acanthodian'-Chondrichthyan Divide|journal=American Museum Novitates|issue=3875|pages=1–15|year=2017|last1=Maisey|first1=John G.|last2=Miller|first2=Randall|last3=Pradel|first3=Alan|last4=Denton|first4=John S.S.|last5=Bronson|first5=Allison|last6=Janvier|first6=Philippe|s2cid=44127090|url=https://www.archive.org/download/pectoralmorphol00mais/pectoralmorphol00mais.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.archive.org/download/pectoralmorphol00mais/pectoralmorphol00mais.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live}}</ref> Dating back to the Middle and Late [[Ordovician]] Period, many isolated scales, made of [[dentine]] and bone, have a structure and growth form that is chondrichthyan-like. They may be the remains of [[stem group|stem]]-chondrichthyans, but their classification remains uncertain.<ref name="Andreev2015">{{cite journal |last1 = Andreev |first1 = Plamen S.|last2=Coates |first2 =Michael I. |last3=Shelton |first3=Richard M. |last4=Cooper |first4=Paul R. |last5=Smith |first5=M. Paul |last6=Sansom |first6=Ivan J. |year=2015 |title=Ordovician chondrichthyan-like scales from North America |journal=[[Palaeontology (journal)|Palaeontology]] |volume=58 |issue=4 |pages=691–704 |doi=10.1111/pala.12167|s2cid = 140675923|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Sansom2012">{{cite journal |last1=Sansom |first1=Ivan J. |last2=Davies |first2= Neil S. |last3=Coates |first3=Michael I. |last4=Nicoll |first4=Robert S. |last5=Ritchie |first5=Alex |year=2012 |title=Chondrichthyan-like scales from the Middle Ordovician of Australia |journal=[[Palaeontology (journal)|Palaeontology]] |volume=55 |issue=2 |pages=243–247 |doi=10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01127.x|bibcode=2012Palgy..55..243S |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Andreev2016">{{cite journal |last1=Andreev |first1=Plamen |last2=Coates |first2=Michael I. |last3=Karatajūtė-Talimaa |first3=Valentina |last4=Shelton |first4=Richard M. |last5=Cooper |first5=Paul R. |last6=Wang |first6=Nian-Zhong |last7=Sansom |first7=Ivan J. |year=2016 |title=The systematics of the Mongolepidida (Chondrichthyes) and the Ordovician origins of the clade |journal=PeerJ |volume=4 |page=e1850 |doi=10.7717/peerj.1850|pmid=27350896 |pmc=4918221 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

The earliest unequivocal fossils of acanthodian-grade cartilaginous fishes are ''[[Qianodus]]'' and ''[[Fanjingshania]]'' from the early Silurian ([[Aeronian]]) of [[Guizhou]], China around 439 million years ago, which are also the oldest unambiguous remains of any jawed vertebrates.<ref name=":12">{{cite journal |last1=Andreev |first1=Plamen S. |last2=Sansom |first2=Ivan J. |last3=Li |first3=Qiang |last4=Zhao |first4=Wenjin |last5=Wang |first5=Jianhua |last6=Wang |first6=Chun-Chieh |last7=Peng |first7=Lijian |last8=Jia |first8=Liantao |last9=Qiao |first9=Tuo |last10=Zhu |first10=Min |date=September 2022 |title=Spiny chondrichthyan from the lower Silurian of South China |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05233-8 |journal=Nature |volume=609 |issue=7929 |pages=969–974 |doi=10.1038/s41586-022-05233-8 |pmid=36171377 |bibcode=2022Natur.609..969A |s2cid=252570103}}</ref><ref name=":02">{{Cite journal |last1=Andreev |first1=Plamen S. |last2=Sansom |first2=Ivan J. |last3=Li |first3=Qiang |last4=Zhao |first4=Wenjin |last5=Wang |first5=Jianhua |last6=Wang |first6=Chun-Chieh |last7=Peng |first7=Lijian |last8=Jia |first8=Liantao |last9=Qiao |first9=Tuo |last10=Zhu |first10=Min |date=2022-09-28 |title=The oldest gnathostome teeth |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05166-2 |journal=Nature |volume=609 |issue=7929 |pages=964–968 |bibcode=2022Natur.609..964A |doi=10.1038/s41586-022-05166-2 |issn=0028-0836 |pmid=36171375 |s2cid=252569771}}</ref> ''Shenacanthus vermiformis'', which lived 436 million years ago, had thoracic armour plates resembling those of placoderms.<ref>{{cite journal | url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36171378/ | pmid=36171378 | year=2022 | last1=Zhu | first1=Y. A. | last2=Li | first2=Q. | last3=Lu | first3=J. | last4=Chen | first4=Y. | last5=Wang | first5=J. | last6=Gai | first6=Z. | last7=Zhao | first7=W. | last8=Wei | first8=G. | last9=Yu | first9=Y. | last10=Ahlberg | first10=P. E. | last11=Zhu | first11=M. | title=The oldest complete jawed vertebrates from the early Silurian of China | journal=Nature | volume=609 | issue=7929 | pages=954–958 | doi=10.1038/s41586-022-05136-8 | bibcode=2022Natur.609..954Z | s2cid=252569910 }}</ref> |

|||

By the start of the Early Devonian, 419 million years ago, [[jawed fish]]es had divided into three distinct groups: the now extinct [[placoderm]]s (a paraphyletic assemblage of ancient armoured fishes), the [[bony fish]]es, and the clade that includes [[spiny sharks]] and early [[cartilaginous fish]]. The modern bony fishes, class [[Osteichthyes]], appeared in the late [[Silurian]] or early Devonian, about 416 million years ago. The first abundant genus of shark, ''[[Cladoselache]]'', appeared in the oceans during the Devonian Period. The first Cartilaginous fishes evolved from ''[[Doliodus]]''-like [[spiny shark]] ancestors. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=10 | Extinct [[Order (biology)|orders]] of cartilaginous fishes |

|||

|- |

|||

! Group |

|||

! Order |

|||

! Image |

|||

! Common name |

|||

! Authority |

|||

! Families |

|||

! Genera |

|||

! Species |

|||

! Note |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(150,80,150)" rowspan=13 | [[Holocephali|<span style="color:white;">Holocephali</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Orodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Orodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Orodus sp1DB.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Petalodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Petalodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Strigilodus tollesonae-novataxa 2023-Hodnett Toomey Olson.jpg|147x147px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Petalodontiformes|Petalodonts]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Zangerl, 1981 |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Members of the holocephali, some genera resembled parrot fish, but some members of the [[Janassidae]] resembled skates. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Helodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Helodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Iniopterygiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Iniopterygiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Iniopteryxrushlaui.JPG|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Members of the holocephali that resembled flying fish, are often characterized by large eyes, large upturned pectoral fins, and club-like tails. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Debeeriiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Debeeriiformes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Symmoriida|<span style="color:white;">†Symmoriida</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Symmorium1DB.jpg|147x147px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Symmoriidae|Symmoriids]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Zangerl, 1981 (sensu Maisey, 2007) |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Members of the holocephali, they were heavily [[sexually dimorphic]].<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Coates | first1 = M. | last2 = Gess | first2 = R. | last3 = Finarelli | first3 = J. | last4 = Criswell | first4 = K. | last5 = Tietjen | first5 = K. | year = 2016 | title = A symmoriiform chondrichthyan braincase and the origin of chimaeroid fishes | journal = Nature | volume = 541| issue = 7636| pages = 208–211| doi = 10.1038/nature20806 | pmid = 28052054 | bibcode = 2017Natur.541..208C | s2cid = 4455946 }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Eugeneodontida|<span style="color:white;">†Eugeneodontida</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Helicoprion_reccon.png|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Eugeneodontida|Eugeneodonts]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Eugeneodontida |

|||

<small></small><small>Zangerl, 1981</small> |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Members of the holocephali, they are characterized by large tooth whorls in their jaws.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tapanila |first1=L |last2=Pruitt |first2=J |last3=Pradel |first3=A |last4=Wilga |first4=C |last5=Ramsay |first5=J |last6=Schlader |first6=R |last7=Didier |first7=D |year=2013 |title=Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion |journal=Biology Letters |volume=9 |issue= 2|page=20130057 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057 |pmid=23445952 |pmc=3639784 }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Psammodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Psammodonti-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Position uncertain |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Copodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Copodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Squalorajiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Squalorajiformes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Chondrenchelyiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Chondrenchelyi-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Chondrenchelys problematica.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Menaspiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Menaspiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:MenaspidDB17.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Cochliodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Cochliodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(150,80,150)" rowspan=1 | [[Squalomorphi|<span style="color:white;">Squalomorph<br />sharks</span>]] |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Protospinaciformes|<span style="color:white;">†Protospinaci-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(150,80,150)" rowspan=6 | <span style="color:white;">Other</span> |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Squatinactiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Squatinactiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Squatinactis NT small.jpg|140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Cappetta et al., 1993 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Protacrodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Protacrodonti-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small> |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Cladoselachiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Cladoselachi-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Cladoselache.png|140x140px]] |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Dean, 1894 |

|||

| align=center | 1 |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Holocephalans, and potential members of the symmoriida. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Xenacanthiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Xenacanthiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Xenacanth.png|147x147px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Xenacanthida|Xenacanths]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Glikman, 1964 |

|||

| align=center | 4 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Eel-like elasmobranchs that were some of the top freshwater predators of the late Paleozoic. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(180,120,180)" | [[Ctenacanthiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Ctenacanthi-<br />formes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Dracopristis hoffmanorum.png|147x147px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Ctenacanthiformes|Ctenacanths]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Glikman, 1964 |

|||

| align=center | 2 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Shark-like elasmobranchs characterized by their robust heads and large dorsal fin spines. |

|||

|- |

|||

| align=center style="background:rgb(165,100,165)" | [[Hybodontiformes|<span style="color:white;">†Hybodontiformes</span>]] |

|||

| [[File:Hybodus hauffianus.png|147x147px]] |

|||

| align=center | [[Hybodontiformes|Hybodonts]] |

|||

| align=center | <small></small>Patterson, 1966 |

|||

| align=center | 5 |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| align=center | |

|||

| valign=top | Shark-like elasmobranchs distinguished by their conical tooth shape, and the presence of a spine on each of their two dorsal fins. |

|||

|} |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

Subphylum '''[[Vertebrata]]''' |

|||

└─'''Infraphylum Gnathostomata''' |

|||

├─[[Placodermi]] — ''extinct'' (armored gnathostomes) |

|||

└'''[[Eugnathostomata]]''' (true jawed vertebrates) |

|||

├─[[Acanthodii]] (stem cartilaginous fish) |

|||

└─Chondrichthyes (true cartilaginous fish) |

|||

├─[[Holocephali]] (chimaeras + several extinct clades) |

|||

└[[Elasmobranchii]] (shark and rays) |

|||

├─[[Selachii]] (true sharks) |

|||

└─[[Batoidea]] (rays and relatives) |

|||

|

|||

*'''Note''': Lines show evolutionary relationships. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[List of cartilaginous fish]] |

|||

* [[Cartilaginous versus bony fishes]] |

|||

* [[Largest organisms#Cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes)|Largest cartilaginous fishes]] |

|||

* [[Threatened rays]] |

|||

* [[Threatened sharks]] |

|||

* [[Placodermi]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

<!------------------------------------------------------------ |

|||

This article uses list-defined references in conjunction with |

|||

the {{r}} and {{sfn}} templates to keep the body |

|||

text clean. Please follow existing examples within the text |

|||

and refer to the following documentation pages if needed: |

|||

List-defined references: |

|||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:LDR |

|||

Template {{r}}: |

|||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:R |

|||

Template {{sfn}}: |

|||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Sfn |

|||

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Footnotes for a |

|||

discussion of different citation methods and how to generate |

|||

footnotes using the <ref> tags. |

|||

-------------------------------------------------------------> |

|||

{{Reflist|30em|refs= |

|||

<!--<ref name="Baez2006">[[John Baez|Baez. John]] (2006) [http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/extinction/ Extinction] University of California. Retrieved 20 January 2013.</ref>--> |

|||

}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{Wikispecies|Chondrichthyes}} |

{{Wikispecies|Chondrichthyes}} |

||

{{ |

{{Wikibooks|Dichotomous Key|Chondrichthyes}} |

||

* [http://www.fmnh.helsinki.fi/users/haaramo/Metazoa/Deuterostoma/Chordata/Chondrichthyes/Chondrichthyes.htm#Elasmobranchii Taxonomy of Chondrichthyes] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20040817003309/http://www.fmnh.helsinki.fi/users/haaramo/Metazoa/Deuterostoma/Chordata/Chondrichthyes/Chondrichthyes.htm#Elasmobranchii Taxonomy of Chondrichthyes] |

||

* [http://www.morphbank.net/Browse/ByImage/?tsn=159785 Images of many sharks, skates and rays on Morphbank] |

* [http://www.morphbank.net/Browse/ByImage/?tsn=159785 Images of many sharks, skates and rays on Morphbank] |

||

{{Chordata}} |

|||

{{Chondrichthyes}} |

|||

{{Evolution of fish}} |

|||

{{Taxonbar|from=Q25371}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Cartilaginous |

[[Category:Cartilaginous fish| ]] |

||

[[Category:Fish classes]] |

|||

[[Category:Pridoli first appearances]] |

|||

[[bs:Rušljoribe]] |

|||

[[Category:Extant Silurian first appearances]] |

|||

[[bg:Хрущялни риби]] |

|||

[[ca:Condricti]] |

|||

[[cs:Paryby]] |

|||

[[da:Bruskfisk]] |

|||

[[de:Knorpelfische]] |

|||

[[et:Kõhrkalad]] |

|||

[[es:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[eo:Kartilagaj fiŝoj]] |

|||

[[fr:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[ko:연골어류]] |

|||

[[hr:Hrskavičnjače]] |

|||

[[is:Brjóskfiskar]] |

|||

[[it:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[he:דגי סחוס]] |

|||

[[la:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[lv:Skrimšļzivis]] |

|||

[[lb:Knorpelfësch]] |

|||

[[lt:Kremzlinės žuvys]] |

|||

[[hu:Porcos halak]] |

|||

[[mk:‘Рскавични риби]] |

|||

[[nl:Kraakbeenvissen]] |

|||

[[ja:軟骨魚綱]] |

|||

[[no:Bruskfisker]] |

|||

[[nn:Bruskfisk]] |

|||

[[oc:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[pl:Ryby chrzęstnoszkieletowe]] |

|||

[[pt:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[qu:K'apa challwa]] |

|||

[[ru:Хрящевые рыбы]] |

|||

[[simple:Chondrichthyes]] |

|||

[[sk:Drsnokožce]] |

|||

[[sr:Рушљорибе]] |

|||

[[fi:Rustokalat]] |

|||

[[sv:Broskfiskar]] |

|||

[[th:ปลากระดูกอ่อน]] |

|||

[[tr:Kıkırdaklı balıklar]] |

|||

[[uk:Хрящові риби]] |

|||

[[zh-yue:軟骨魚綱]] |

|||

[[zh:軟骨魚綱]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 04:21, 21 March 2024

| Cartilaginous fishes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Example of cartilaginous fishes: Elasmobranchii at the top of the image and Holocephali at the bottom of the image. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Clade: | Eugnathostomata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes Huxley, 1880 |

| Living subclasses and orders | |

| |

Chondrichthyes (/kɒnˈdrɪkθi.iːz/; from Ancient Greek χόνδρος (khóndros) 'cartilage', and ἰχθύς (ikhthús) 'fish') is a class of jawed fish that contains the cartilaginous fish or chondrichthyians, which all have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage. They can be contrasted with the Osteichthyes or bony fish, which have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. Chondrichthyes are aquatic vertebrates with paired fins, paired nares, placoid scales, conus arteriosus in the heart, and a lack of opecula and swim bladders. Within the infraphylum Gnathostomata, cartilaginous fishes are distinct from all other jawed vertebrates.

The class is divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, skates and sawfish) and Holocephali (chimaeras, sometimes called ghost sharks, which are sometimes separated into their own class). Extant Chondrichthyes range in size from the 10 cm (3.9 in) finless sleeper ray to the over 10 m (33 ft) whale shark.

Anatomy[edit]

Skeleton[edit]

The skeleton is cartilaginous. The notochord is gradually replaced by a vertebral column during development, except in Holocephali, where the notochord stays intact. In some deepwater sharks, the column is reduced.[9]

As they do not have bone marrow, red blood cells are produced in the spleen and the epigonal organ (special tissue around the gonads, which is also thought to play a role in the immune system). They are also produced in the Leydig's organ, which is only found in certain cartilaginous fishes. The subclass Holocephali, which is a very specialized group, lacks both the Leydig's and epigonal organs.

Appendages[edit]

Apart from electric rays, which have a thick and flabby body, with soft, loose skin, chondrichthyans have tough skin covered with dermal teeth (again, Holocephali is an exception, as the teeth are lost in adults, only kept on the clasping organ seen on the caudal ventral surface of the male), also called placoid scales (or dermal denticles), making it feel like sandpaper. In most species, all dermal denticles are oriented in one direction, making the skin feel very smooth if rubbed in one direction and very rough if rubbed in the other.

Originally, the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which do not contain any dermal elements, did not connect. In later forms, each pair of fins became ventrally connected in the middle when scapulocoracoid and puboischiadic bars evolved. In rays, the pectoral fins are connected to the head and are very flexible.

One of the primary characteristics present in most sharks is the heterocercal tail, which aids in locomotion.[10]

Body covering[edit]

Chondrichthyans have tooth-like scales called dermal denticles or placoid scales. Denticles usually provide protection, and in most cases, streamlining. Mucous glands exist in some species, as well.

It is assumed that their oral teeth evolved from dermal denticles that migrated into the mouth, but it could be the other way around, as the teleost bony fish Denticeps clupeoides has most of its head covered by dermal teeth (as does, probably, Atherion elymus, another bony fish). This is most likely a secondary evolved characteristic, which means there is not necessarily a connection between the teeth and the original dermal scales.

The old placoderms did not have teeth at all, but had sharp bony plates in their mouth. Thus, it is unknown whether the dermal or oral teeth evolved first. It has even been suggested[by whom?] that the original bony plates of all vertebrates are now gone and that the present scales are just modified teeth, even if both the teeth and body armor had a common origin a long time ago. However, there is currently no evidence of this.

Respiratory system[edit]

All chondrichthyans breathe through five to seven pairs of gills, depending on the species. In general, pelagic species must keep swimming to keep oxygenated water moving through their gills, whilst demersal species can actively pump water in through their spiracles and out through their gills. However, this is only a general rule and many species differ.

A spiracle is a small hole found behind each eye. These can be tiny and circular, such as found on the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum), to extended and slit-like, such as found on the wobbegongs (Orectolobidae). Many larger, pelagic species, such as the mackerel sharks (Lamnidae) and the thresher sharks (Alopiidae), no longer possess them.

Nervous system[edit]

In chondrichthyans, the nervous system is composed of a small brain, 8–10 pairs of cranial nerves, and a spinal cord with spinal nerves.[11] They have several sensory organs which provide information to be processed. Ampullae of Lorenzini are a network of small jelly filled pores called electroreceptors which help the fish sense electric fields in water. This aids in finding prey, navigation, and sensing temperature. The Lateral line system has modified epithelial cells located externally which sense motion, vibration, and pressure in the water around them. Most species have large well-developed eyes. Also, they have very powerful nostrils and olfactory organs. Their inner ears consist of 3 large semicircular canals which aid in balance and orientation. Their sound detecting apparatus has limited range and is typically more powerful at lower frequencies. Some species have electric organs which can be used for defense and predation. They have relatively simple brains with the forebrain not greatly enlarged. The structure and formation of myelin in their nervous systems are nearly identical to that of tetrapods, which has led evolutionary biologists to believe that Chondrichthyes were a cornerstone group in the evolutionary timeline of myelin development.[12]

Immune system[edit]

Like all other jawed vertebrates, members of Chondrichthyes have an adaptive immune system.[13]

Reproduction[edit]

Fertilization is internal. Development is usually live birth (ovoviviparous species) but can be through eggs (oviparous). Some rare species are viviparous. There is no parental care after birth; however, some chondrichthyans do guard their eggs.

Capture-induced premature birth and abortion (collectively called capture-induced parturition) occurs frequently in sharks/rays when fished.[14] Capture-induced parturition is often mistaken for natural birth by recreational fishers and is rarely considered in commercial fisheries management despite being shown to occur in at least 12% of live bearing sharks and rays (88 species to date).[14]

Classification[edit]

The class Chondrichthyes has two subclasses: the subclass Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, skates, and sawfish) and the subclass Holocephali (chimaeras). To see the full list of the species, click here.

| Subclasses of cartilaginous fishes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elasmobranchii |

|

Elasmobranchii is a subclass that includes the sharks and the rays and skates. Members of the elasmobranchii have no swim bladders, five to seven pairs of gill clefts opening individually to the exterior, rigid dorsal fins, and small placoid scales. The teeth are in several series; the upper jaw is not fused to the cranium, and the lower jaw is articulated with the upper. The eyes have a tapetum lucidum. The inner margin of each pelvic fin in the male fish is grooved to constitute a clasper for the transmission of sperm. These fish are widely distributed in tropical and temperate waters.[15] |

| Holocephali |

|

Holocephali (complete-heads) is a subclass of which the order Chimaeriformes is the only surviving group. This group includes the rat fishes (e.g., Chimaera), rabbit-fishes (e.g., Hydrolagus) and elephant-fishes (Callorhynchus). Today, they preserve some features of elasmobranch life in Paleaozoic times, though in other respects they are aberrant. They live close to the bottom and feed on molluscs and other invertebrates. The tail is long and thin and they move by sweeping movements of the large pectoral fins. There is an erectile spine in front of the dorsal fin, sometimes poisonous. There is no stomach (that is, the gut is simplified and the 'stomach' is merged with the intestine), and the mouth is a small aperture surrounded by lips, giving the head a parrot-like appearance.

The fossil record of the Holocephali starts in the Devonian period. The record is extensive, but most fossils are teeth, and the body forms of numerous species are not known, or at best poorly understood. |

| Extant orders of cartilaginous fishes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Order | Image | Common name | Authority | Families | Genera | Species | Note | ||||

| Total | ||||||||||||

| Galean sharks |

Carcharhiniformes |

|

ground sharks |

Compagno, 1977 | 8 | 51 | >270 | 7 | 10 | 21 | ||

| Heterodontiformes |

|

bullhead sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||||||

| Lamniformes |

|

mackerel sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1958 | 7 +2 extinct |

10 | 16 | 10 | |||||

| Orectolobiformes |

|

carpet sharks |

Applegate, 1972 | 7 | 13 | 43 | 7 | |||||

| Squalomorph sharks |

Hexanchiformes |

|

frilled and cow sharks |

de Buen, 1926 | 2 +3 extinct |

4 +11 extinct |

7 +33 extinct |

|||||

| Pristiophoriformes | sawsharks | L. S. Berg, 1958 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||||||

| Squaliformes |

|

dogfish sharks |

Goodrich, 1909 | 7 | 23 | 126 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Squatiniformes |

|

angel sharks |

Buen, 1926 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Rays | Myliobatiformes |

|

stingrays and relatives |

Compagno, 1973 | 10 | 29 | 223 | 1 | 16 | 33 | ||

| Rhinopristiformes |

|

sawfishes | 1 | 2 | 5–7 | 5–7 | ||||||

| Rajiformes |

|

skates and guitarfishes |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 5 | 36 | >270 | 4 | 12 | 26 | |||

| Torpediniformes |

|

electric rays |

de Buen, 1926 | 2 | 12 | 69 | 2 | 9 | ||||

| Holocephali | Chimaeriformes |

|

chimaera | Obruchev, 1953 | 3 +2 extinct |

6 +3 extinct |

39 +17 extinct |

|||||

| Taxonomy according to Leonard Compagno, 2005[16] with additions from [17] |

|---|

* position uncertain |

Evolution[edit]