Human cannibalism: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1224611878 by Rich Farmbrough (talk) – not strictly needed, but it's always good to avoid long sections of text without images – if you disagree, let's take it to the talk page |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Practice of humans eating other humans}} |

|||

{{redirect|Cannibal}} |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{otheruses4|consuming one's own species|usage about marketing and mechanical recycling|Cannibalization}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Use Oxford spelling|date=April 2024}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=April 2024}} |

|||

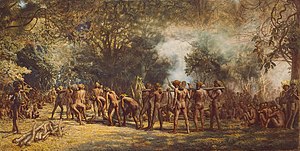

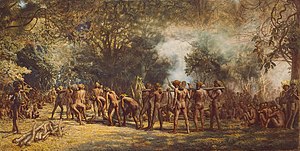

[[File:Cannibalism on Tanna.jpeg|thumb|right|upright=1.35|A cannibal feast on [[Tanna (island)|Tanna]], Vanuatu, {{circa|1885–1889}}]] |

|||

{{homicide}} |

|||

'''Human cannibalism''' is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices [[cannibalism]] is called a '''cannibal'''. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into [[zoology]] to describe animals consuming parts of individuals of the same species as food. |

|||

Both [[Early modern human|anatomically modern humans]] and [[Neanderthal]]s practised cannibalism to some extent in the [[Pleistocene]],<ref>{{cite journal|title=Neanderthals Were Cannibals, Bones Show |doi=10.1126/science.286.5437.18b |publisher=Sciencemag.org |date=October 1, 1999 |last1=Culotta|first1=E.|journal=Science|volume=286|issue=5437|pages=18b–19|pmid=10532879 |s2cid=5696570 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Archaeologists Rediscover Cannibals |doi=10.1126/science.277.5326.635 |publisher=Sciencemag.org |date=August 1, 1997 |last1=Gibbons|first1=A.|journal=Science|volume=277|issue=5326|pages=635–637|pmid=9254427|s2cid=38802004 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rougier |first1=Hélène |last2=Crevecoeur |first2=Isabelle |last3=Beauval |first3=Cédric |last4=Posth |first4=Cosimo |last5=Flas |first5=Damien |last6=Wißing |first6=Christoph |last7=Furtwängler |first7=Anja |last8=Germonpré |first8=Mietje |last9=Gómez-Olivencia |first9=Asier |last10=Semal |first10=Patrick |last11=van der Plicht |first11=Johannes |last12=Bocherens |first12=Hervé |last13=Krause |first13=Johannes |date=July 6, 2016 |title=Neandertal cannibalism and Neandertal bones used as tools in Northern Europe |journal=Scientific Reports |language=en |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=29005 |doi=10.1038/srep29005 |pmid=27381450 |pmc=4933918 |bibcode=2016NatSR...629005R |issn=2045-2322}}</ref><ref name=nhm-oldest-evidence>{{cite web |last1=Davis |first1=Josh |title=Oldest evidence of human cannibalism as a funerary practice |url=https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/october/oldest-evidence-of-human-cannibalism-as-a-funerary-practice.html |website=Natural History Museum – Science News |access-date=February 26, 2024 |language=en |date=October 4, 2023}}</ref> and Neanderthals may have been eaten by modern humans as the latter spread into [[Europe]].<ref>{{Cite news|first=Robin |last=McKie |date=May 17, 2009 |title=How Neanderthals Met a Grisly Fate: Devoured by Humans |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2009/may/17/neanderthals-cannibalism-anthropological-sciences-journal |work=The Observer |access-date=May 18, 2009 | location=London}}</ref> Cannibalism was occasionally practised in [[Egypt]] during [[ancient Egypt|ancient]] and [[Roman Egypt|Roman times]], as well as later during severe famines.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HbcCqIC5358C&q=copts+practicing+cannibalism&pg=PA149|title=A History of Egypt: From Earliest Times to the Present|last=Thompson|first=Jason|date=2008|publisher=American University in Cairo Press|isbn=978-977-416-091-2|language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|pp=47–55}} |

|||

[[Image:Cannibals.23232.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Cannibalism in [[Brazil]] in 1557 as alleged by [[Hans Staden]].]] |

|||

The [[Island Carib]]s of the [[Lesser Antilles]], whose name is the origin of the word ''cannibal'', acquired a long-standing reputation as eaters of human flesh, reconfirmed when their legends were recorded in the 17th century.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Myers|first=Rovert A. |title=Island Carib Cannibalism |date=1984 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41849170 |journal=Nieuwe West-Indische Gids / New West Indian Guide |volume=58 |issue=3/4 |pages=147–184 |jstor=41849170 |issn=0028-9930}}</ref> Some controversy exists over the accuracy of these legends and the prevalence of actual cannibalism in the culture. |

|||

'''Cannibalism''' (from [[Spanish language|Spanish]] {{lang|es|''caníbal''}}, in connection with alleged cannibalism among the [[Carib]]s), also called '''anthropophagy''' (from [[Greek language|Greek]] [[wiktionary:ἄνθρωπος|{{lang|grc|''anthropos''}}]] "man" and [[wiktionary:-phage|{{lang|el|''phagein''}}]] "to consume") is the act or practice of [[human]]s consuming other humans. In [[zoology]], the term cannibalism is extended to refer to any [[species]] consuming members of its own kind. |

|||

Cannibalism has been well documented in much of the world, including [[Fiji]] (once nicknamed the "Cannibal Isles"),<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sanday |first1=Peggy Reeves |title=Divine Hunger: Cannibalism as a Cultural System |date=1986 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge, UK |isbn=978-0-521-31114-4 |page=151 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SYW6EzB9rYkC |language=en}}</ref> the [[Amazon Basin]], the [[Congo Basin|Congo]], and the [[Māori people]] of New Zealand.<ref name="history">{{Cite book |

|||

Care should be taken to distinguish among ritual cannibalism sanctioned by a [[cultural code]], cannibalism by necessity occurring in extreme situations of [[famine]], and cannibalism by [[Mental illness|mentally disturbed]] people. |

|||

| last = Rubinstein |

|||

| first = William D. |

|||

| author-link1 = William Rubinstein |

|||

| title = Genocide: A History |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=nMMAk4VwLLwC&pg=PA17 |

|||

| publisher = Routledge |

|||

| location = New York |

|||

| year = 2014 |

|||

| pages = 17–18 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-582-50601-5 }} |

|||

</ref> Cannibalism was also practised in [[New Guinea]] and in parts of the [[Solomon Islands (archipelago)|Solomon Islands]], and human flesh was sold at markets in some parts of [[Melanesia]]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Knauft |first1=Bruce M. |title=From ''Primitive'' to ''Postcolonial'' in Melanesia and Anthropology |date=1999 |publisher=[[University of Michigan Press]] |isbn=978-0-472-06687-2 |page=104 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YM18gG16Z7YC&pg=PA104 |language=en}}</ref> and of the [[Congo Basin]].{{sfn|Edgerton|2002|p=109}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=118–121}} A form of cannibalism popular in early modern Europe was the consumption of body parts or blood for [[Medical cannibalism|medical purposes]]. Reaching its height during the 17th century, this practice continued in some cases into the second half of the 19th century.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sugg |first1=Richard |title=Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians |date=2015 |publisher=Routledge |pages=122–125 and passim}}</ref> |

|||

Cannibalism has occasionally been practised as a last resort by people suffering from [[famine]]. Well-known examples include the ill-fated [[Donner Party]] (1846–1847), the [[Holodomor]] (1932–1933), and the crash of [[Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571]] (1972), after which the survivors ate the bodies of the dead. Additionally, there are cases of people engaging in cannibalism for sexual pleasure, such as [[Albert Fish]], [[Issei Sagawa]], [[Jeffrey Dahmer]], and [[Armin Meiwes]]. Cannibalism has been both practised and fiercely condemned in recent several wars, especially in [[Liberia]]<ref>{{cite web |last1=Schmall |first1=Emily |title=Liberia's elections, ritual killings and cannibalism |url=https://theworld.org/dispatch/news/regions/africa/110728/ritual-killing-liberia-elections-politics |website=GlobalPost |access-date=November 22, 2023 |date=August 1, 2011}}</ref> and the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/2661365.stm|title=UN Condemns DR Congo Cannibalism|publisher=BBC|date=January 15, 2003|access-date=October 29, 2011}}</ref> It was still practised in [[Papua New Guinea]] as of 2012, for cultural reasons.<ref name="nzherald.co.nz">{{Cite news|title = Cannibal Cult Members Arrested in PNG|url = http://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=10817610|work= [[The New Zealand Herald]] |date = July 5, 2012|access-date = November 28, 2015|issn = 1170-0777|language = en-NZ}}</ref><ref name="Sleeping with Cannibals">{{cite web |last=Raffaele |first=Paul |date=September 2006 |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/sleeping-with-cannibals-128958913/ |title=Sleeping with Cannibals |work=[[Smithsonian (magazine)|Smithsonian Magazine]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Origin of the term== |

|||

[[Richard Hakluyt]]'s ''Voyages'' introduced the word to English. Shakespeare transposed it, anagram-fashion, to name his monster servant in ''[[The Tempest (play)|The Tempest]]'' '[[Caliban (character)|Caliban]]'. |

|||

Cannibalism has been said to test the bounds of [[cultural relativism]] because it challenges anthropologists "to define what is or is not beyond the pale of acceptable human behavior".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Conklin |first1=Beth A. |title=Consuming Grief: Compassionate Cannibalism in an Amazonian Society |date=2001 |publisher=University of Texas Press |location=Austin |isbn=0-292-71232-4 |page=3}}</ref> A few scholars argue that no firm evidence exists that cannibalism has ever been a socially acceptable practice anywhere in the world,{{sfn|Arens|1979}} but such views have been largely rejected as irreconcilable with the actual evidence.<ref name="Lévi-Strauss-p87">{{cite book |last1=Lévi-Strauss |first1=Claude |title=We Are All Cannibals, and Other Essays |date=2016 |publisher=Columbia University Press |location=New York |page=87}}</ref>{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|pp=475–476, 491}} |

|||

[[Image:Cannibalism 1571.PNG|266px|thumb|right|Cannibalism in [[Muscovy]] and [[Lithuania]] [[1571]]]] |

|||

== |

==Etymology== |

||

The word "cannibal" is derived from Spanish ''caníbal'' or ''caríbal'', originally used as a name variant for the [[Kalinago]] (Island Caribs), a people from the [[West Indies]] said to have eaten human flesh.<ref>{{cite web |title=Cannibal Definition |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/cannibal |website=Dictionary.com |access-date=June 25, 2023 |language=en}}</ref> The older term ''anthropophagy'', meaning "eating humans", is also used for human cannibalism.<ref name="britannica cannibalism">{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/92701/cannibalism |title=Cannibalism (human behaviour) |website=Britannica |access-date=June 25, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

The [[social stigma]] against cannibalism has been used as an aspect of propaganda against an enemy by accusing them of acts of cannibalism to separate them from their [[humanity]]. New research points to the fact that early man practiced cannibalism. Genetic markers commonly found in modern humans all over the world could be evidence that our earliest ancestors were cannibals, according to new research. Scientists suggest that today some people carry a gene that evolved as protection against brain diseases that can be spread by consuming human flesh.<ref name="Cannibalism Normal in the Past">{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/04/0410_030410_cannibal.html|publisher="National Geographic"|title="Cannibalism Normal?"|}}</ref> |

|||

==Reasons and types== |

|||

The [[Carib]] tribe acquired a longstanding reputation as cannibals following the recording of their legends by [[Fr. Breton]] in the 17th century. Some controversy exists over the accuracy of these legends and the prevalence of actual cannibalism in the culture. |

|||

Cannibalism has been practised under a variety of circumstances and for various motives. To adequately express this diversity, [[Shirley Lindenbaum]] suggests that "it might be better to talk about 'cannibalisms{{' "}} in the plural.{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=480}} |

|||

According to a decree by Queen [[Isabella of Castile]] and also later under British colonial rule, [[slavery]] was considered to be illegal unless the people involved were so depraved that their conditions as slaves would be better than as free men. Demonstrations of cannibalistic tendencies were considered evidence of such depravity, and hence reports of cannibalism became widespread.<ref>Brief history of cannibal controversies; David F. Salisbury, August 15, 2001</ref> This legal requirement might have led to conquerors exaggerating the extent of cannibalistic practices, or inventing them altogether. |

|||

===Institutionalized, survival, and pathological cannibalism=== |

|||

The [[Korowai]] tribe of southeastern [[Papua (Indonesian province)|Papua]] could be one of the last surviving tribes in the world engaging in cannibalism. |

|||

One major distinction is whether cannibal acts are accepted by the culture in which they occur – ''institutionalized cannibalism'' – or whether they are merely practised under starvation conditions to ensure one's immediate survival – ''survival cannibalism'' – or by isolated individuals considered criminal and often pathological by society at large – ''cannibalism as psychopathology'' or "aberrant behavior".{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|pp=475, 477}} |

|||

[[Marvin Harris]] has analysed cannibalism and other [[taboo food and drink|food taboos]]. |

|||

Institutionalized cannibalism, sometimes also called "learned cannibalism", is the consumption of human body parts as "an institutionalized practice" generally accepted in the culture where it occurs.{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=2}} |

|||

He argued that it was common when humans lived in small bands, but disappeared in the transition to states, the [[Aztecs]] being an exception. |

|||

[[File:Mignonette.jpg|thumb|Sketch of the ''Mignonette'' by Tom Dudley. In English common law, the [[R v Dudley and Stephens|R v Dudley and Stephens (1884)]] case banned survival cannibalism after maritime disasters, which had been a widely accepted [[custom of the sea]].]] |

|||

By contrast, survival cannibalism means "the consumption of others under conditions of starvation such as shipwreck, military siege, and famine, in which persons normally averse to the idea are driven [to it] by the will to live".{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=477}} Also known as ''famine cannibalism'',<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ó Gráda |first1=Cormac |title=Eating People Is Wrong, and Other Essays on Famine, Its Past, and Its Future |date=2015 |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton |isbn=978-1-4008-6581-9 |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FICSBQAAQBAJ}}</ref>{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=18–20}} such forms of cannibalism resorted to only in situations of extreme necessity have occurred in many cultures where cannibalism is otherwise clearly rejected. The survivors of the shipwrecks of the ''[[Essex (whaleship)|Essex]]'' and ''[[French frigate Méduse (1810)|Méduse]]'' in the 19th century are said to have engaged in cannibalism, as did the members of [[Franklin's lost expedition]] and the [[Donner Party]]. |

|||

Such cases often involve only ''necro-cannibalism'' (eating the corpse of someone already dead) as opposed to ''homicidal cannibalism'' (killing someone for food). In modern English law, the latter is always considered a crime, even in the most trying circumstances. The case of ''[[R v Dudley and Stephens]]'', in which two men were found guilty of murder for killing and eating a cabin boy while adrift at sea in a lifeboat, set the precedent that [[necessity in English criminal law|necessity]] is no defence to a charge of murder. This decision outlawed and effectively ended the practice of shipwrecked sailors drawing lots in order to determine who would be killed and eaten to prevent the others from starving, a time-honoured practice formerly known as a "[[custom of the sea]]".<ref>{{cite book |last=Simpson |first=A. W. B. |title=Cannibalism and the Common Law: The Story of the Tragic Last Voyage of the Mignonette and the Strange Legal Proceedings to Which It Gave Rise |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1984 |isbn=978-0-226-75942-5 |location=Chicago |url=https://archive.org/details/cannibalismcommo0000simp |url-access = registration}}</ref> |

|||

A well known case of mortuary cannibalism is that of the [[Fore (people)|Fore]] tribe in [[New Guinea]] which resulted in the spread of the disease [[Kuru epidemic|Kuru]]. It is often believed to be well-documented, although no eyewitnesses have ever been at hand. Some scholars argue that although post-mortem dismemberment was the practice during funeral rites, cannibalism was not. [[Marvin Harris]] theorizes that it happened during a famine period coincident with the arrival of Europeans and was rationalized as a religious rite. |

|||

In other cases, cannibalism is an expression of a psychopathology or [[mental disorder]], condemned by the society in which it occurs and "considered to be an indicator of [a] severe personality disorder or psychosis".{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=477}} Well-known cases include [[Albert Fish]], [[Issei Sagawa]], and [[Armin Meiwes]]. Fantasies of cannibalism, whether acted out or not, are not specifically mentioned in manuals of mental disorders such as the ''[[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders|DSM]]'', presumably because at least serious cases (that lead to murder) are very rare.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Adams |first1=Cecil |title=Eat or Be Eaten: Is Cannibalism a Pathology as Listed in the DSM-IV? |url=http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2515/eat-or-be-eaten |website=[[The Straight Dope]] |access-date=March 16, 2010 |language=en |date=July 2, 2004}}</ref> |

|||

In pre-modern medicine, an explanation for cannibalism stated that it came about within a black acrimonious [[Four humours|humour]], which, being lodged in the linings of the [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricle]], produced the voracity for human flesh.<ref>{{1728}} [http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/HistSciTech/HistSciTech-idx?type=turn&entity=HistSciTech000900240147&isize=L Anthropophagy].</ref> |

|||

===Exo-, endo-, and autocannibalism=== |

|||

==Historical accounts== |

|||

===Early history era=== |

|||

*In [[Germany]] some experts like Emil Carthaus and Dr. Bruno Bernhard found 1,891 signs of cannibalism in the [[caves]] at the [[Hönne]] (BC 1000 - 700). |

|||

Within institutionalized cannibalism, ''exocannibalism'' is often distinguished from ''endocannibalism''. [[Endocannibalism]] refers to the consumption of a person from the same community. Often it is a part of a [[funeral|funerary]] ceremony, similar to [[burial]] or [[cremation]] in other cultures. The consumption of the recently deceased in such rites can be considered "an act of affection"{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=478}} and a major part of the grieving process.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Woznicki |first=Andrew N. |year=1998 |title=Endocannibalism of the Yanomami |url=http://users.rcn.com/salski/No18-19Folder/Endocannibalism.htm |journal=The Summit Times |volume=6 |issue=18–19}}</ref> It has also been explained as a way of guiding the souls of the dead into the bodies of living descendants.<ref name=DowEncyc>{{cite book |last=Dow |first=James W. |editor-last=Tenenbaum |editor-first=Barbara A. |chapter-url=https://files.oakland.edu/users/dow/web/personal/papers/cannibal/cannibal.html |chapter=Cannibalism |title=Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture – Volume 1 |pages=535–537 |publisher=Charles Scribner's Sons |location=New York |access-date=September 30, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111007090705/https://files.oakland.edu/users/dow/web/personal/papers/cannibal/cannibal.html |archive-date=October 7, 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

* Cannibalism is reported in the [[Bible]] during the siege [[Samaria]] (2 Kings 6:25-30). Two women made a pact to eat their children, but after the first mother cooked her child, the second mother ate it but refused to reciprocate by cooking her own child. Almost exactly the same story is reported by [[Flavius Josephus]] during the siege of Jerusalem by Rome in 70AD. |

|||

[[File:Theodore de Bry - America tertia pars 4.jpg|thumb|upright=1.15|Enemies being killed and roasted in South America – engraving by [[Theodor de Bry]] (1592)]] |

|||

* Cannibalism was documented in [[Egypt]] during a famine caused by the failure of the [[Nile]] to flood for eight years (AD 1064-1073). |

|||

In contrast, [[exocannibalism]] is the consumption of a person from outside the community. It is frequently "an act of aggression, often in the context of warfare",{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=478}} where the flesh of killed or captured enemies may be eaten to celebrate one's victory over them.<ref name=DowEncyc/> |

|||

Some scholars explain both types of cannibalism as due to a belief that eating a person's flesh or internal organs will endow the cannibal with some of the positive characteristics of the deceased.<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Goldman |editor-first=Laurence |year=1999 |title=The Anthropology of Cannibalism |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QyiDClqjwSUC&pg=PA16 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |page=16 |isbn=978-0-89789-596-5}}</ref> However, several authors investigating exocannibalism in [[New Zealand]], [[New Guinea]], and the [[Congo Basin]] observe that such beliefs were absent in these regions.{{sfn|Moon|2008|p=157}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Seligman |first1=Charles Gabriel |title=The Melanesians of British New Guinea |author1-link=Charles Gabriel Seligman |date=1910 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |pages=552 |url=https://archive.org/details/melanesiansofbri00seli}}</ref>{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=38, 102}} |

|||

* [[St. Jerome]], in his letter ''[[Against Jovinianus]]'', tells of meeting members of a British tribe, the [[Atticoti]], while traveling in [[Gaul]]. According to Jerome, the Britons claimed that they enjoyed eating "the buttocks of the shepherds and the breasts of their women" as a delicacy (ca. 360 AD). In 2001, archaeologists at the University of Bristol found evidence of [[Iron Age]] cannibalism in Gloucestershire[http://www.bristol.ac.uk/news/2001/cannibal.htm] |

|||

A further type, different from both exo- and endocannibalism, is ''[[autocannibalism]]'' (also called ''autophagy'' or ''self-cannibalism''), "the act of eating parts of oneself".{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=479}} It does not ever seem to have been an institutionalized practice, but occasionally occurs as pathological behaviour, or due to other reasons such as curiosity. Also on record are instances of forced autocannibalism committed as acts of aggression, where individuals are forced to eat parts of their own bodies as a form of [[torture]].{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=479}} |

|||

===Middle Ages=== |

|||

* Cannibalism was practiced by the participants of the [[First Crusade]]. Due to lack of food some of the crusaders fed on the bodies of their dead opponents after the capture of the Arab town of [[Ma'arrat al-Numan]]. [[Amin Maalouf]] also discusses further cannibalism incidents on the march to [[Jerusalem]], and to the efforts made to delete mention of these from western history. (Amin Maalouf, The Crusades through Arab Eyes. Schocken, 1989, ISBN 0-8052-0898-4). |

|||

===Additional motives and explanations=== |

|||

* In Europe during the [[Great Famine of 1315–1317]], at a time when [[Dante]] was writing one of the most significant pieces of literature in western history and the [[Renaissance]] was just beginning, there were widespread reports of cannibalism throughout Europe. However, many historians have since dismissed these reports as fanciful and ambiguous. The ''canto'' 33 of [[The Divine Comedy|Dante's Inferno]] ambiguously refers to [[Ugolino della Gherardesca]] eating his own sons while starving in prison. |

|||

Exocannibalism is thus often associated with the consumption of enemies as an act of aggression, a practice also known as ''war cannibalism''.{{sfn|Boulestin|Coupey|2015|p=120}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=15}} Endocannibalism is often associated with the consumption of deceased relatives in funerary rites driven by affection – a practice known as ''funerary''{{sfn|Boulestin|Coupey|2015|p=120}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=14}} or ''mortuary cannibalism''.<ref name=petrinovich-p6>{{cite book |last1=Petrinovich |first1=Lewis F. |title=The Cannibal Within |date=2000 |publisher=Aldine Transaction |location=New York |isbn=0-202-02048-7 |page=6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QauRWfX4NTcC}}</ref> But acts of institutionalized cannibalism can also be driven by various other motives, for which additional names have been coined.'' |

|||

* Cannibalism was reported in [[Mexico]], the [[flower war]]s of the [[Aztec]] Empire being considered as the most massive manifestation of cannibalism, but the Aztec accounts, written after the conquest, reported that human flesh was considered by itself to be of no value, and usually thrown away and replaced with turkey. There are only two Aztec accounts on this subject: one comes from the [[Ramirez codex]], and the most elaborated account on this subject comes from [[Juan Bautista de Pomar]], the grandson of [[Netzahualcoyotl]], [[tlatoani]] of [[Texcoco (Aztec site)|Texcoco]]. The accounts differ little. Juan Bautista wrote that after the sacrifice, the Aztec warriors received the body of the victim, then they boiled it to separate the flesh from the bones, then they would cut the meat in very little pieces, and send them to important people, even from other towns; the recipient would rarely eat the meat, since they considered it an honour, but the meat had no value by itself. In exchange, the warrior would get jewels, decorated blankets, precious feathers and slaves; the purpose was to encourage successful warriors. There were only two ceremonies a year where war captives were sacrificed. Although the Aztec empire has been called "The Cannibal Kingdom", there is no evidence in support of its being a widespread custom. |

|||

[[File:Albarello_MUMIA_18Jh.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.85|An 18th-century [[albarello]] used for storing [[mummia]]. [[Medicinal cannibalism]] was widespread in many countries of early modern Europe.]] |

|||

* Aztecs believed that there were man-eating tribes in the south of Mexico; the only illustration known showing an act of cannibalism shows an Aztec being eaten by a tribe from the south ([[Florentine Codex]]). In the [[siege of Tenochtitlan]], there was a severe hunger in the city; people reportedly ate lizards, grass, insects, and mud from the lake, but there are no reports on cannibalism of the dead bodies. |

|||

''[[Medicinal cannibalism]]'' (also called ''medical cannibalism'') means "the ingestion of human tissue ... as a supposed medicine or tonic". In contrast to other forms of cannibalism, which Europeans generally frowned upon, the "medicinal ingestion" of various "human body parts was widely practiced throughout [[Europe]] from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries", with early records of the practice going back to the first century CE.{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=478}} It was also frequently practised in [[China]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pettersson |first1=Bengt |title=Cannibalism in the Dynastic Histories |journal=Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities |date=1999 |volume=71 |pages=121, 167–180}}</ref> |

|||

''Sacrificial cannibalism'' refers the consumption of the flesh of victims of [[human sacrifice]], for example among the [[Aztecs]].{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=479}} Human and animal remains excavated in [[Knossos]], [[Crete]], have been interpreted as evidence of a ritual in which children and sheep were sacrificed and eaten together during the [[Bronze Age]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Recht |first1=Laerke |title=Symbolic Order: Liminality and Simulation in Human Sacrifice in the Bronze-Age Aegean and Near East |journal=Journal of Religion and Violence |date=2014 |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=411–412 |doi=10.5840/jrv20153101 |jstor=26671439 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26671439 |issn=2159-6808}}</ref> According to [[Ancient Rome|Ancient Roman]] reports, the [[Celts]] in [[Great Britain|Britain]] practised sacrificial cannibalism,<ref name=druids-sacrifice>{{cite web |last1=Owen |first1=James |title=Druids Committed Human Sacrifice, Cannibalism? |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/druids-sacrifice-cannibalism |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210320080851/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/druids-sacrifice-cannibalism |url-status=dead |archive-date=March 20, 2021 |website=National Geographic |access-date=May 1, 2023 |language=en |date=March 20, 2009}}</ref> and archaeological evidence backing these claims has by now been found.<ref name=cannibalistic-celts>{{cite web |title=Cannibalistic Celts discovered in South Gloucestershire |url=http://www.bristol.ac.uk/news/2001/cannibal.htm |website=University of Bristol |access-date=May 1, 2023 |date=March 7, 2001}}</ref> |

|||

* The friar [[Diego de Landa]] reported about [[Yucatán]] instances, ''Yucatan before and after the Conquest'', translated from ''Relación de las cosas de Yucatan, 1566'' (New York: Dover Publications, 1978: 4), and there have been similar reports by Purchas from Popayán, [[Colombia]], and from the [[Marquesas Islands]] of [[Polynesia]], where human flesh was called ''long-pig'' (Alanna King, ed., ''Robert Louis Stevenson in the South Seas,'' London: Luzac Paragon House, 1987: 45-50). It is recorded about the natives of the captaincy of [[Sergipe]] in [[Brazil]], ''They eat [[human flesh]] when they can get it, and if a woman miscarries devour the abortive immediately. If she goes her time out, she herself cuts the [[umbilical cord|navel-string]] with a [[seashell|shell]], which she boils along with the secondine, and eats them both.'' (See E. Bowen, 1747: 532.)]] |

|||

''Infanticidal cannibalism'' or ''cannibalistic infanticide'' refers to cases where newborns or infants are killed because they are "considered unwanted or unfit to live" and then "consumed by the mother, father, both parents or close relatives".{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=14}}{{sfn|Travis-Henikoff|2008|p=196}} |

|||

===Early modern era=== |

|||

[[Infanticide]] followed by cannibalism was practised in various regions, but is particularly well documented among [[Aboriginal Australians]].{{sfn|Travis-Henikoff|2008|p=196}}{{sfn|Bates|1938|loc=chapters 10, 17}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Róheim |first1=Géza |author-link1= Géza Róheim |title=Children of the Desert: The Western Tribes of Central Australia |volume=1 |date=1976 |publisher=Harper & Row |location=New York |pages=69, 71–72}}</ref> Among animals, such behaviour is called ''[[filial cannibalism]]'', and it is common in many species, especially among fish.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bose |first=Aneesh P. H. |date=2022 |title=Parent–Offspring Cannibalism throughout the Animal Kingdom: A Review of Adaptive Hypotheses |journal=Biological Reviews |language=en |volume=97 |issue=5 |pages=1868–1885 |doi=10.1111/brv.12868 |pmid=35748275 |s2cid=249989939 |issn=1464-7931|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Forbes |first1=Scott |title=A Natural History of Families |date=2005 |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton |isbn=978-1-4008-3723-6 |page=171 |doi=10.1515/9781400837236 |url=https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400837236}}</ref> |

|||

''Human predation'' is the hunting of people from unrelated and possibly hostile groups in order to eat them. In parts of the [[Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests]], hunting people "was an opportunistic extension of seasonal [[foraging]] or pillaging strategies", with human bodies just as welcome as those of animals as sources of protein, according to the anthropologist Bruce M. Knauft. As populations living near coasts and rivers were usually better nourished and hence often physically larger and stronger than those living inland, they "raided inland 'bush' peoples with impunity and often with little fear of retaliation".{{sfn|Knauft|1999|p=139}} Cases of human predation are also on record for the neighbouring [[Bismarck Archipelago]]{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=190–192}} and for [[Australia]].{{sfn|Bates|1938|loc=ch. 11}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lumholtz |first1=Carl |author-link1=Carl Sofus Lumholtz |title=Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years' Travels in Australia and of Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland |date=1889 |publisher=C. Scribner's Sons |location=New York |pages=72, 176, 271–274 |url=https://archive.org/details/amongcannibalsac1889lumh}}</ref> In the Congo Basin, there lived groups such as the [[Zappo Zap]]s who hunted humans for food even when game was plentiful.<ref name=Phipps-pp138-139>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KsX_G2FQ078C |title=William Sheppard: Congo's African American Livingstone |first=William E. |last=Phipps |publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |date=2002 |pages=138–139 |isbn=0-664-50203-2}}</ref>{{sfn|Edgerton|2002|p=87}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=216–221}} |

|||

* In the [[Netherlands|Dutch]] ''[[rampjaar]]'' (disaster year) of [[1672]], when [[France]] and [[England]] attacked the republic during the [[Franco-Dutch War]]/[[Third Anglo-Dutch War]], [[Johan de Witt]] (a significant [[Netherlands|Dutch]] [[political figure]]) was killed by a shot in the neck; his naked body was hung and mutilated and the heart was carved out to be exhibited. His brother was shot, stabbed, [[eviscerate]]d alive, hanged naked, brained and partly eaten. |

|||

[[File:A cannibal scene with human flesh roasting by Herbert Ward.jpg|thumb|upright=0.85|"A cannibal scene with human flesh roasting over the fire" – drawing from the [[Congo Basin]] by [[Herbert Ward (sculptor)|Herbert Ward]] (1891)]] |

|||

* Howard Zinn describes cannibalism by early [[Jamestown, Virginia|Jamestown]] settlers in his book ''A'' ''People's History of the United States''. |

|||

The term ''gastronomic cannibalism'' has been suggested for cases where human flesh is eaten to "provide a supplement to the regular diet"<ref name=petrinovich-p6/> – thus essentially for its nutritional value – or, in an alternative definition, for cases where it is "eaten without ceremony (other than culinary), in the same manner as the flesh of any other animal".{{sfn|Travis-Henikoff|2008|p=24}} While the term has been criticized as being too vague to clearly identify a specific type of cannibalism,{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=16–17}} various records indicate that nutritional or culinary concerns could indeed play a role in such acts even outside of periods of starvation. Referring to the Congo Basin, where many of the eaten were butchered [[slavery|slaves]] rather than enemies killed in war, the anthropologist [[Emil Torday]] notes that "the most common [reason for cannibalism] was simply gastronomic: the natives loved 'the flesh that speaks' [as human flesh was commonly called] and paid for it".<ref name="Siefkes 2022 97">Torday cited in {{harvnb|Siefkes|2022|p=97}}.</ref> The historian Key Ray Chong observes that, throughout Chinese history, "learned cannibalism was often practiced ... for culinary appreciation".{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=viii}} |

|||

* An event occurring in the western New York territory ("Seneca Country") U.S.A., during 1687 was later described in this letter sent to France: “On the 13th (of July) about four o’clock in the afternoon, having passed through two dangerous defiles (narrow gorges), we arrived at the third where we were vigorously attacked by 800 Senecas, 200 of whom fired, wishing to attack our rear whilst the remainder of their force would attack our front, but the resistance they met produced such a great consternation that they soon resolved to fly. All our troops were so overpowered by the extreme heat and the long journey we had made that we were obliged to bivouac (camp) on the field until the morrow. We witnessed the painful Sight of the usual cruelties of the savages who cut the dead into quarters, as in slaughter houses, in order to put them into the pot (dinner); the greater number were opened while still warm that their blood might be drank. our rascally ''outaouais'' (Ottawa Indians) distinguished themselves particularly by these barbarities and by their poltroonery (cowardice), for they withdrew from the combat;..." -- Canadian Governor, the [[Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville, Marquis de Denonville|Marquis de Denonville]]. |

|||

In his popular book ''[[Guns, Germs and Steel]]'', [[Jared Diamond]] suggests that "protein starvation is probably also the ultimate reason why cannibalism was widespread in traditional New Guinea highland societies",<ref>{{cite book |last1=Diamond |first1=Jared |author1-link=Jared Diamond |title=Guns, Germs and Steel |title-link=Guns, Germs and Steel |date=2017 |publisher=Vintage |isbn=978-0-09-930278-0 |edition=UK |page=149 |orig-date=1997}}</ref> and both in New Zealand and [[Fiji]], cannibals explained their acts as due to a lack of animal meat.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=29, 213}} In [[Liberia]], a former cannibal argued that it would have been wasteful to let the flesh of killed enemies spoil,{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=126}} and eaters of human flesh in the Bismarck Archipelago expressed the same sentiment.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=236, 243–244}} In many cases, human flesh was also described as particularly delicious, especially when it came from women, children, or both. Such statements are on record for various regions and peoples, including the Aztecs,{{sfn|Travis-Henikoff|2008|p=158}} today's Liberia{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=105}} and [[Nigeria]],{{sfn|Hogg|1958|pp=89–90}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=62, 105}} the [[Fang people]] in west-central Africa,{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=105}} the Congo Basin,{{sfn|Edgerton|2002|p=86}}<ref name=Phipps-pp138-139/>{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=62, 64, 105–106, 114, 125, 142}} China up to the 14th century,{{sfn|Chong|1990|pp=128, 137, 144}}{{sfn|Pettersson|1999|p=141}} [[Sumatra]],{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=48}} [[Borneo]],<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bickmore |first1=Albert S. |author-link1=Albert S. Bickmore |title=Travels in the East Indian Archipelago |date=1868 |publisher=John Murray |location=London |page=425 |url=https://archive.org/details/travelsineastind00bick}}</ref> Australia,{{sfn|Bates|1938|loc=ch. 11}}{{sfn|Lumholtz|1889|pp=271–272}} New Guinea,{{sfn|Hogg|1958|p=130}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=193}} New Zealand,{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=36}} and Fiji{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=193, 213–215}} as well as various other [[Melanesia]]n and [[Polynesia]]n islands.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=193, 205, 246}} |

|||

* In [[1729]] [[Jonathan Swift]] wrote ''A Modest Proposal: For Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick'', commonly referred to as ''[[A Modest Proposal]]'', a [[satire|satirical]] [[pamphlet]] in which he proposed that poor [[Ireland|Irish]] families sell their children to be eaten, thereby earning income for the family. It was written as an attack on the indifference of landlords to the state of their tenants and on the political economists with their calculations on the schemes to raise income. |

|||

There is a debate among anthropologists on how important [[biological functionalism|functionalist]] reasons are for the understanding of institutionalized cannibalism. Diamond is not alone in suggesting "that the consumption of human flesh was of nutritional benefit for some populations in New Guinea" and the same case has been made for other "tropical peoples ... exploiting a diverse range of animal foods", including human flesh. The [[cultural materialism (anthropology)|materialist]] anthropologist [[Marvin Harris]] argued that a "shortage of animal protein" was also the underlying reason for Aztec cannibalism.{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=480}} The cultural anthropologist [[Marshall Sahlins]], on the other hand, rejected such explanations as overly simplistic, stressing that cannibal customs must be regarded as "complex phenomen[a]" with "myriad attributes" which can only be understood if one considers "symbolism, ritual, and cosmology" in addition to their "practical function".{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|pp=480–481, 483 (citing and summarizing Sahlins)}} |

|||

* The survivors of the sinking of the French ship [[The Raft of the Medusa|Medusa]] in 1816 resorted to cannibalism after four days adrift on a raft. |

|||

While not a motive, the term ''innocent cannibalism'' has been suggested for cases of people eating human flesh without knowing what they are eating. It is a subject of myths, such as the myth of [[Thyestes]] who unknowingly ate the flesh of his own sons.{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|p=479}} There are also actual cases on record, for example from the Congo Basin, where cannibalism had been quite widespread and where even in the 1950s travellers were sometimes served a meat dish, learning only afterwards that the meat had been of human origin.{{sfn|Edgerton|2002|p=109}}{{sfn|Hogg|1958|pp=114–115}} |

|||

* After the sinking of the [[Whaleship Essex|Whaleship ''Essex'']] of [[Nantucket]] by a whale, on [[November 20]], [[1820]], (an important source event for [[Herman Melville]]'s ''[[Moby Dick]]'') the survivors, in three small boats, resorted, by common consent, to cannibalism in order for some to survive [http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/alabaster/A671492]. See [[The Custom of the Sea]]. |

|||

In pre-modern medicine, an explanation given by the now-discredited theory of [[humorism]] for cannibalism was that it was caused by a black acrimonious humor, which, being lodged in the linings of the [[ventricle (heart)|ventricles]] of the heart, produced a voracity for human flesh.<ref>{{cite book |title=Cyclopædia |title-link=Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences |publisher=1728 |page=[https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/A4C5AV6Q7LZ5DY8E/pages/AERODNFSAGUB2N8X?view=one 107] |chapter=Anthropophagy}}</ref> On the other hand, the French philosopher [[Michel de Montaigne]] understood war cannibalism as a way of expressing vengeance and hatred towards one's enemies and celebrating one's victory over them, thus giving an interpretation that is close to modern explanations. He also pointed out that some acts of Europeans in his own time could be considered as equally barbarous, making his essay "[[Of Cannibals]]" ({{circa|1580}}) a precursor to later ideas of [[cultural relativism]].{{sfn|Lindenbaum|2004|pp=480, 484}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Montaigne |first1=Michel de |title=Essays |title-link=Essays (Montaigne) |date=1595 |chapter=On Cannibals |chapter-url=http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/montaignecannibals.htm |at=Book 1, ch. 31 }}</ref> |

|||

* The Acadian Recorder (a newspaper published out of [[Halifax, Nova Scotia|Halifax]] in the early 1800s) published an article in its May 27, 1826, issue telling of the wreck of the ship 'Francis Mary', en route from New Brunswick to Liverpool, England, with a load of timber. The article describes how the survivors sustained themselves by eating those who perished.<ref>''The Acadian Recorder'', Saturday, May 27, 1826</ref> |

|||

== Body parts and culinary practices == |

|||

* Sir [[John Franklin]]'s lost polar expedition and the [[Donner Party]] are other examples of human cannibalism from the [[1840s]]. |

|||

=== Nutritional value of the human body === |

|||

* The case of ''[[R v. Dudley and Stephens]]'' ([[1884]]) 14 QBD 273 (QB) is an [[England|English]] case which is said to be one of the origins of the defense of [[necessity]] in modern common law. The case dealt with four crewmembers of an English yacht which were cast away in a storm some 1600 miles from the [[Cape of Good Hope]]. After several days one of the crew fell unconscious due to a combination of the famine and drinking sea-water. The others (one objecting) decided then to kill him and eat him. They were picked up four days later. The fact that not everyone had agreed to draw lots contravened [[The Custom of the Sea]] and was held to be murder. At the trial was the first recorded use of the defense of necessity. |

|||

Archaeologist James Cole investigated the nutritional value of the human body and found it to be similar to that of animals of similar size.{{sfn|Cole|2017|p=1}} |

|||

He notes that, according to ethnographic and archaeological records, nearly all edible parts of humans were sometimes eaten – not only [[skeletal muscle]] tissue ("flesh" or "meat" in a narrow sense), but also "[[lung]]s, [[liver]], [[human brain|brain]], [[heart]], [[nervous tissue]], [[bone marrow]], [[genitalia]] and [[human skin|skin]]", as well as [[kidney]]s.{{sfn|Cole|2017|pp=2–3}} For a typical adult man, the combined nutritional value of all these edible parts is about 126,000 [[Calorie#Nutrition|kilocalorie]]s (kcal).{{sfn|Cole|2017|p=3}} The nutritional value of women and younger individuals is lower because of their lower body weight – for example, around 86% of a male adult for an adult woman and 30% for a boy aged around 5 or 6.{{sfn|Cole|2017|p=3}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=133}} |

|||

As the daily energy need of an adult man is about 2,400 kilocalories, a dead male body could thus have feed a group of 25 men for a bit more than two days, provided they ate nothing but the human flesh alone – longer if it was part of a mixed diet.{{sfn|Cole|2017|pp=5, 7}} The nutritional value of the human body is thus not insubstantial, though Cole notes that for prehistoric hunters, large [[megafauna]] such as [[mammoth]]s, [[rhinoceros]], and [[bisons]] would have been an even better deal as long as they were available and could be caught, because of their much higher body weight.{{sfn|Cole|2017|pp=6–7}} |

|||

* In the [[1870s]], in the U.S. state of [[Colorado]], a man named [[Alfred Packer]] was accused of killing and eating his travelling companions. He was later released due to a legal technicality, and throughout his life maintained that he was innocent of the murders. However, modern forensic evidence, unavailable during Packer's lifetime, indicates that he did murder and/or eat several of his companions. The story of Alfred Packer was satirically told in the [[Trey Parker]] comedy/horror/musical film, ''[[Cannibal! The Musical]]'', released in 1996 by [[Troma]] Studios. The main food court at the [[University of Colorado at Boulder]] is named the Alferd Packer Grill. |

|||

=== Hearts and livers === |

|||

* In [[1884]], the [[Mignonette]], a small [[yacht]] bound for [[Australia]], was overturned. The three survivors drifted on a [[dinghy]] for four weeks, fed by the remains of a cabin boy whom they had murdered. When they returned to [[England]], they were found guilty of murder on the argument that hunger, like poverty, does not justify murder (''Albany Law Journal'', [[13 December]] 1884). |

|||

Cases of people eating human [[liver]]s and [[heart]]s, especially of enemies, have been reported from across the world. After the [[Battle of Uhud]] (625), [[Hind bint Utba]] ate (or at least attempted to) the liver of [[Hamza ibn Abd al-Muttalib]], an uncle of [[Muhammad]]. At that time, the liver was considered "the seat of life".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Orlandi |first1=Riccardo |last2=Cianci |first2=Nicole |last3=Invernizzi |first3=Pietro |last4=Cesana |first4=Giancarlo |date=August 2018 |title='I Miss My Liver.' Nonmedical Sources in the History of Hepatocentrism |journal=Hepatology Communications |volume=2 |issue=8 |page=989 |doi=10.1002/hep4.1224|pmid=30094408 |pmc=6078213 }}</ref> |

|||

French Catholics ate livers and hearts of [[Huguenots]] at the [[St. Bartholomew's Day massacre]] in 1572, in some cases also offering them for sale.<ref>{{cite book |last=Roberts |first=Penny |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5sahCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT53 |title=Crowd Actions in Britain and France from the Middle Ages to the Modern World |date=2015 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-137-31651-6 |editor-last=Davis |editor-first=Michael T. |edition=illustrated |chapter=Riot and Religion in Sixteenth-Century France |pages=35–36}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Vandenberg |first1=Vincent |title=De chair et de sang: Images et pratiques du cannibalisme de l'Antiquité au Moyen Âge |series=Tables des hommes |date=2014 |publisher=Presses universitaires François-Rabelais |location=Tours |isbn=978-2-86906-828-5 |url=https://books.openedition.org/pufr/23892 |language=fr |at=ch. 2}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Tang Wuzong.jpg|thumb|upright=.85|[[Emperor Wuzong of Tang]] supposedly ate [[heart]]s and [[liver]]s of teenagers to cure his illness]] |

|||

===Modern era=== |

|||

In China, [[medical cannibalism]] was practised over centuries. People voluntary cut their own body parts, including parts of their livers, and boiled them to cure ailing relatives.{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=102}} Children were sometimes killed because eating their boiled hearts was considered a good way of extending one's life.{{sfn|Chong|1990|pp=143–144}} [[Emperor Wuzong of Tang]] supposedly ordered provincial officials to send him "the hearts and livers of fifteen-year-old boys and girls" when he had become seriously ill, hoping in vain this medicine would cure him. Later private individuals sometimes followed his example, paying soldiers who kidnapped preteen children for their kitchen.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=275–276}} |

|||

[[Image:Maaselkä cannibalism.jpg|thumb|220px|[[Finland|Finnish]] soldiers displaying the skins of the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] soldiers who were eaten by their fellow soldiers at Maaselkä. Original caption: "An enemy recon patrol that was cutten out of food supplies had butchered a few members of their own patrol group, and had eaten most of them."]] |

|||

* A well-documented case occurred in [[Chichijima]] in 1945,{{Fact|date=February 2007}} when Japanese soldiers killed and ate eight downed American airmen. This case was investigated in 1947 in a war-crimes trial, and of 30 Japanese soldiers prosecuted, five (Maj. Matoba, Gen. Tachibana, Adm. Mori, Capt. Yoshii and Dr. Teraki) were found guilty and hanged. |

|||

When "human flesh and organs were sold openly at the marketplace" during the [[Taiping Rebellion]] in 1850–1864, human hearts became a popular dish, according to some who afterwards freely admitted having consumed them.{{sfn|Chong|1990|pp=106}} |

|||

* [[John F. Kennedy]] during his service in World War II believed that a boy from the [[Solomon Islands]] that was his servant bragged of eating a Japanese soldier. Native islanders also in their historical culture also practiced [[headhunting]].<ref> PT 109 by Donovan (book)</ref> |

|||

According to a missionary's report from the brutal suppression of the [[Dungan Revolt (1895–1896)|Dungan Revolt of 1895–1896]] in northwestern China, "thousands of men, women and children were ruthlessly massacred by the imperial soldiers" and "many a meal of human hearts and livers was partaken of by soldiers", supposedly out of a belief that this would give them "the courage their enemies had displayed".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Rijnhart |first1=Susie Carson |title=With the Tibetans in Tent and Temple: Narrative of Four Years' Residence on the Tibetan Border, and of a Journey into the Far Interior |date=1901 |publisher=Foreign Christian Missionary Society |location=Cincinnati |page=92 |edition=5 |url=https://archive.org/details/withtibetansinte00rijn}}</ref> |

|||

In World War II, Japanese soldiers ate the livers of killed Americans in the [[Chichijima incident]].<ref>{{Cite web |author-last1=Budge |author-first1=Kent G. |title=Mori Kunizo (1890–1949) |url=http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/M/o/Mori_Kunizo.htm |date=2012 |access-date=August 18, 2021 |website=The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia}}</ref> |

|||

* ''[[The New York Times]]'' reporter [[William Buehler Seabrook]], in the interests of research, obtained from a hospital intern at the [[Sorbonne]] a chunk of human meat from the body of a healthy human killed by accident, and cooked and ate it. He reported that, "It was like good, fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef. It was very definitely like that, and it was not like any other meat I had ever tasted. It was so nearly like good, fully developed veal that I think no person with a palate of ordinary, normal sensitiveness could distinguish it from veal. It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy, but not too tough or stringy to be agreeably edible. The roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable."<ref>William Bueller Seabrook. ''Jungle Ways'' London, Bombay, Sydney: George G. Harrap and Company, 1931</ref> |

|||

Many Japanese soldiers who died during the occupation of [[Jolo]] Island in the [[Philippines]] had their livers eaten by local [[Moro people|Moro]] fighters, according to Japanese soldier Fujioka Akiyoshi.<ref name=Matthiessen-Pan-Asianism-p172>{{cite book |last=Matthiessen |first=Sven |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=llPeCgAAQBAJ&dq=%22Fujioka+described+the+utmost+brutality+of+the+Moros,+who+had+killed%22&pg=PA172 |title=Japanese Pan-Asianism and the Philippines from the Late Nineteenth Century to the End of World War II: Going to the Philippines Is Like Coming Home? |date=2015 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-30572-4 |series=Brill's Japanese Studies Library |location= |page=172}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Cultural Revolution]] (1966–1976), hundreds of incidents of cannibalism occurred, mostly motivated by hatred against supposed "class enemies", but sometimes also by health concerns.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Song|first=Yongyi|author-link=Song Yongyi|date=August 25, 2011|title=Chronology of Mass Killings during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976)|url=https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/chronology-mass-killings-during-chinese-cultural-revolution-1966-1976|access-date=July 12, 2023|website=[[Sciences Po]]|language=en}}</ref> In a case recorded by the local authorities, a school teacher in [[Mengshan County]] "heard that consuming a 'beauty's heart' could cure disease". He then chose a 13- or 14-year-old student of his and publicly denounced her as a member of the enemy faction, which was enough to get her killed by an angry mob. After the others had left, he "cut open the girl's chest ..., dug out her heart, and took it home to enjoy".{{sfn|Zheng|2018|p=53}} |

|||

*References to cannibalizing the enemy has also been seen in poetry written when China was repressed in the [[Song Dynasty]], though the cannibalizing sounds more like poetic symbolism to express the hatred towards the enemy. (See ''[[Man Jiang Hong]]'') The Chinese hate-cannibalism was reported during WWII also. (Key Ray Chong:Cannibalism in China, 1990) |

|||

In a further case that took place in [[Wuxuan County]], likewise in the [[Guangxi]] region, three brothers were beaten to death as supposed enemies; afterwards their livers were cut out, baked, and consumed "as medicine".{{sfn|Zheng|2018|p=89}} |

|||

According to the Chinese author Zheng Yi, who researched these events, "the consumption of human liver was mentioned at least fifty or sixty times" in just a small number of archival documents.{{sfn|Zheng|2018|p=26}} He talked with a man who had eaten human liver and told him that "barbecued liver is delicious".{{sfn|Zheng|2018|p=30}} |

|||

During a massacre of the [[Madurese people|Madurese]] minority in the [[Indonesia]]n part of [[Borneo]] in 1999, reporter Richard Lloyd Parry met a young cannibal who had just participated in a "human barbecue" and told him without hesitation: "It tastes just like chicken. Especially the liver – just the same as chicken."<ref name=Parry-Apocalypse>{{cite web |last1=Parry |first1=Richard Lloyd |title=Apocalypse now: With the cannibals of Borneo |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/apocalypse-now-1082766.html |website=The Independent |access-date=December 13, 2023 |language=en |date=March 25, 1999}}</ref> In 2013, during the [[Syrian civil war]], Syrian rebel Abu Sakkar was filmed eating parts of the lung or liver of a government soldier while declaring that "We will eat your hearts and your livers you soldiers of [[Bashar al-Assad|Bashar]] the dog".<ref>{{Cite news |last=Wood |first=Paul |date=July 5, 2013 |title=Face-to-face with Abu Sakkar, Syria's 'heart-eating cannibal' |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-23190533}}</ref> |

|||

* During the [[1930s]], anecdotal accounts of cannibalism were reported from the [[Ukraine]] during the [[Holodomor]]. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/3229000.stm] |

|||

=== Breasts, palms, and soles === |

|||

*In his book [[Flyboys: A True Story of Courage]], James Bradley details several instances of cannibalism of WWII Allied prisoners by their Japanese captors. The author claims that this included not only ritual cannibalization of the livers of freshly-killed prisoners, but also the cannibalization-for-sustenance of living prisoners over the course of several days, amputating limbs only as needed to keep the meat fresh. |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| total_width = 150 |

|||

| image1 = Breasts close-up (4).jpg |

|||

| alt1 = Photography of female breasts |

|||

| image2 = Palm, fingers.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = Front of a human's left hand |

|||

| image3 = Bare soles soft.jpg |

|||

| alt3 = Bare soles on the beach |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| footer = Women's [[breast]]s as well as human [[Palm of the hand|palms]] and sometimes [[Sole (foot)|soles]] made popular eating in various parts of the world |

|||

}} |

|||

Various accounts from around the world mention women's [[breast]]s as a |

|||

* [[Alexander Solzhenitsyn]] in ''[[The Gulag Archipelago]]'', amongst others, retold how cannibalism was rife amongst Soviet prisoners in German [[prisoner of war]] camps. |

|||

favourite body part. Also frequently mentioned are the [[palm of the hand|palms of the hand]]s and sometimes the [[sole (foot)|soles of the foots]], regardless of the victim's gender. |

|||

[[Jerome]], in his treatise ''[[Against Jovinianus]]'', claimed that the British [[Attacotti]] were cannibals who |

|||

*Cannibalism was reported by at least one reliable witness, the journalist Neil Davis during the South East Asian wars of the 1960s and 1970s. Davis reported that Khmer (Cambodian) troops ritually ate portions of the slain enemy, typically the liver. However he, and many refugees, also report that cannibalism was practised non-ritually when there was no food to be found. This usually occurred when towns and villages were under [[Khmer Rouge]] control, and food was strictly rationed, leading to widespread starvation. Any civilian caught participating in cannibalism would have been immediately executed.<ref>Tim Bowden. ''One Crowded Hour''. ISBN 0-00-217496-0</ref> |

|||

regarded the [[buttocks]] of men and the breasts of women as delicacies.<ref name=Jerome-Jovinianus>{{Cite book |

|||

|title=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church |

|||

|volume=6 |

|||

|contribution=Against Jovinianus – Book II |

|||

|date=1893 |

|||

|publisher=The Christian Literature Company |

|||

|location=New York |

|||

|access-date=May 20, 2023 |

|||

|page=[https://archive.org/details/selectlibraryofn06schauoft/page/394 394] |

|||

|url=https://archive.org/details/selectlibraryofn06schauoft |

|||

|editor1-first=Philip |

|||

|editor1-last=Schaff |

|||

|editor2-first=Henry |

|||

|editor2-last=Wace |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Mongol invasion of Europe]] in the 13h century and their subsequent rule over China during the [[Yuan dynasty]] (1271–1368), some [[Mongols|Mongol]] fighters practised cannibalism and both European and Chinese observers record a preference for women's breasts, which were considered "delicacies" and, if there were many corpses, sometimes the only part of a female body that was eaten (of men, only the [[thigh]]s were said to be eaten in such circumstances).{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=270–271}} |

|||

After meeting a group of cannibals in West Africa in the 14th century, the Moroccan explorer [[Ibn Battuta]] recorded that, according to their preferences, "the tastiest part of women's flesh is the palms and the breast."<ref name=Levtzion-Hopkins-p298>{{cite book |editor1-last=Levtzion |editor1-first=N. |editor2-last=Hopkins |editor2-first=J. F. P. |title=Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History |date=1981 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |pages=298}}</ref> |

|||

*Cannibalism has been reported in several recent [[Africa]]n conflicts, including the [[Second Congo War]], and the civil wars in [[Liberia]] and [[Sierra Leone]]. Typically, this is apparently done in desperation, as during peacetime cannibalism is much less frequent. Even so, it is sometimes directed at certain groups believed to be relatively helpless, such as Congo [[Pygmies]]. It is also reported by some that [[witch doctor|African traditional healers]] sometimes use the body parts of children in their medicine. In the 1970s the Ugandan dictator [[Idi Amin]] was reputed to practise cannibalism, but the stories were never conclusively proved.{{Fact|date=March 2007}} |

|||

Centuries later, the anthropologist {{interlanguage link|Percy Amaury Talbot|fr}} wrote that, in southern [[Nigeria]], "the parts in greatest favour are the palms of the hands, the fingers and toes, and, of a woman, the breast."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Talbot |first1=Percy Amaury |title=The Peoples of Southern Nigeria |date=1926 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=London |volume=3 |page=827}}</ref> |

|||

Regarding the north of the country, his colleague [[Charles Kingsley Meek]] added: "Among all the cannibal tribes the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet were considered the tit-bits of the body."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Meek |first1=C. K. |author-link1=Charles Kingsley Meek |title=The Northern Tribes of Nigeria |volume=2 |date=1925 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=London |page=55 |url=https://archive.org/details/the-northern-tribes-of-nigeria_202208}}</ref> |

|||

Among the Apambia, a cannibalistic clan of the [[Azande people]] in Central Africa, the palms of the hands and the soles of the foots were considered the best parts of the human body, while their favourite dish was prepared with "fat from a woman's breast", according to the missionary and ethnographer F. Gero.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gero |first1=F. |title=Cannibalism in Zandeland: Truth and Falsehood |publisher=Editrice Missionaria Italiana |location=Bologna |pages=79, 82}}</ref> |

|||

Similar preferences are on record throughout [[Melanesia]]. According to the anthropologists [[Bernard Deacon (anthropologist)|Bernard Deacon]] and [[Camilla Wedgwood]], women were "specially fattened for eating" in [[Vanuatu]], "the breasts being the great delicacy". A missionary confirmed that "a body of a female usually formed the principal part of the repast" at feasts for chiefs and warriors.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=195}} |

|||

* On [[October 13]], [[1972]], a [[Uruguay]]an [[Rugby union|rugby]] team flew across the [[Andes]] to play a game in [[Chile]]. The plane crashed near the border between Chile and [[Argentina]]. After several weeks of [[starvation]] and struggle for [[Survival skills|survival]], the numerous survivors decided to eat the frozen bodies of the deceased in order to survive. They were rescued over two months later. ''See [[Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571]].'' The 1993 film [[Alive: The Miracle of the Andes|''Alive'']] tells the story of this ordeal. |

|||

The ethnologist {{interlanguage link|Felix Speiser|de}} writes: "Apart from the breasts of women and the genitals of men, palms of hands and soles of feet were the most coveted morsels." He knew a chief on [[Ambae]], one of the islands of Vanuatu, who, "according to fairly reliably sources", dined on a young girl's breasts every few days.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Speiser |first1=Felix |title=Ethnology of Vanuatu: An Early Twentieth Century Study |date=1991 |publisher=Crawford House |location=Bathurst, New South Wales |page=217}}</ref>{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=195}} |

|||

When visiting the [[Solomon Islands]] in the 1980s, anthropologist Michael Krieger met a former cannibal who told him that women's breasts had been considered the best part of the human body because they were so fatty, with fat being a rare and sought delicacy.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Krieger |first1=Michael |title=Conversations with the Cannibals: The End of the Old South Pacific |date=1994 |publisher=Ecco |location=Hopewell, NJ |page=187}}</ref>{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=195}} |

|||

They were also considered among the best parts in [[New Guinea]] and the [[Bismarck Archipelago]].{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=194}}{{sfn|Hogg|1958|p=151}} |

|||

=== Modes of preparation === |

|||

* It has been reported by defectors and refugees that, at the height of the famine in the [[1990s]], cannibalism was sometimes practiced in [[North Korea]]. |

|||

Based on theoretical considerations, the [[structuralism|structuralist]] anthropologist [[Claude Lévi-Strauss]] suggested that human flesh was most typically [[Boiling#In cooking|boiled]], with [[roasting]] also used to prepare the bodies of enemies and other outsiders in [[exocannibalism]], but rarely in funerary [[endocannibalism]] (when eating deceased relatives).{{sfn|Shankman|1969|p=58}} |

|||

* [[Médecins Sans Frontières]], the international medical charity, supplied photographic and other documentary evidence of ritualised cannibal feasts among the participants in [[Liberia]]'s internecine strife in the 1980s to representatives of [[Amnesty International]] who were on a fact-finding mission to the neighbouring state of [[Guinea]]. However, Amnesty International declined to publicise this material, the Secretary-General of the organization, [[Pierre Sane]], stating at the time in an internal communication that "what they do with the bodies after human rights violations are committed is not part of our mandate or concern". The existence of cannibalism on a wide scale in Liberia was subsequently verified in video documentaries by [[Journeyman Pictures]] of [[London]]. |

|||

But an analysis of 60 sufficiently detailed and credible descriptions of institutionalized cannibalism by anthropologist Paul Shankman failed to confirm this hypothesis.{{sfn|Shankman|1969|pp=60–63}} Shankman found that roasting and boiling together accounted for only about half of the cases, with roasting being slightly more common. In contrast to Lévi-Strauss's predictions, boiling was more often used in exocannibalism, while roasting was about equally common for both.{{sfn|Shankman|1969|pp=60–62}} |

|||

Shankman observed that various other "ways of preparing people" were repeatedly employed as well; in one third of all cases, two or more modes where used together (e.g. some bodies or body parts were boiled or baked, while others were roasted).{{sfn|Shankman|1969|pp=61–62}} Human flesh was [[steaming|baked in steam]] on preheated rocks or in [[earth oven]]s (a technique widely used in the Pacific), [[smoking (cooking)|smoked]] (which allowed to preserve it for later consumption), or eaten raw.{{sfn|Shankman|1969|pp=60–62}} While these modes were used in both exo- and endocannibalism, another method that was only used in the latter and only in the Americas was to burn the bones or bodies of deceased relatives and then to consume the bone ash.{{sfn|Shankman|1969|pp=61–62}} |

|||

* In September 2006, Australian television crews from ''[[60 Minutes (Australia)|60 Minutes]]'' and ''[[Today Tonight]]'' attempted to rescue a 6-year-old boy who they believed would be ritually cannibalised by his tribe, the [[Korowai]], from Papua, Indonesia. |

|||

After analysing numerous accounts from China, Key Ray Chong similarly concludes that "a variety of methods for cooking human flesh" were used in this country. Most popular were "[[broiling]], roasting, boiling and steaming", followed by "[[pickling]] in salt, wine, sauce and the like".{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=157}} Human flesh was also often "cooked into [[soup]]" or [[stew]]ed in cauldrons.{{sfn|Chong|1990|pp=153–155}} Eating human flesh raw was the "least popular" method, but a few cases are on record too.{{sfn|Chong|1990|pp=156–157}} Chong notes that human flesh was typically cooked in the same way as "ordinary foodstuffs for daily consumption" – no principal distinction from the treatment of animal meat is detectable, and nearly any mode of preparation used for animals could also be used for people.{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=157}} |

|||

* On [[April 13]], [[1995]], it was reported by the Electronic Telegraph that there are hospitals in [[Shenzhen]], P.R.C., that sell aborted [[fetus|fetuses]] for human consumption. Several of the doctors at the hospitals openly admitted to consuming the fetuses regularly for "health benefits;" one added that the "best" were first-born males of young women. Another said that the fetuses were sometimes sent to factories for use in the production of medicines. [http://www.churchofeuthanasia.org/snuffit3/eatfetus.html] |

|||

=== Whole-body roasting and baking === |

|||

==Cannibalism by necessity== |

|||

Though human corpses, like those of animals, were usually cut into pieces for further processing, reports of people being roasted or baked whole are on record throughout the world. |

|||

Cannibalism is also sometimes practiced as a last resort by people suffering from [[famine]]. In the [[United States|US]], the group of settlers known as the [[Donner party]] resorted to cannibalism while snowbound in the mountains for the winter. The last survivors of Sir [[John Franklin]]'s Expedition were found to have resorted to cannibalism in their final push across King William Island towards the Back River.<ref>Beattie, Owen and Geiger, John (2004). ''Frozen in Time.'' ISBN 1-55365-060-3.</ref> There are disputed claims that cannibalism was widespread during the famine in [[Ukraine]] in the [[1930s]], during the [[Siege of Leningrad]] in [[World War II]],<ref>http://observer.guardian.co.uk/life/story/0,6903,605454,00.html</ref><ref>http://condor.depaul.edu/~rrotenbe/aeer/aeer13_2/Dickenson.html</ref><ref>http://www.sovietarmy.com/books/leningrad.html</ref> and during the [[Chinese Civil War]] and the [[Great Leap Forward]] in the [[People's Republic of China]]. There were also rumours of several cannibalism outbreaks durining World War II in the concentration camps where the Jews were malnurished. Cannibalism was also practiced by Japanese troops as recently as WWII in the Pacific theater.<ref>Tanaka, Toshiyuki, and Tanaka, Yuki (1996). ''Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II.'' ISBN 0-8133-2717-2.</ref> A more recent example is of leaked stories from [[North Korean]] refugees of cannibalism practiced during and after a famine that occurred sometime between 1995 and 1997.<ref>http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A41966-2003Oct3?language=printer</ref> |

|||

At the [[Herxheim (archaeological site)|archaeological site of Herxheim]], Germany, more than a thousand people were killed and eaten about 7000 years ago, and the evidence indicates that many of them were [[rotisserie|spit-roasted]] whole over open fires.{{sfn|Boulestin|Coupey|2015|pp=101, 115}} |

|||

During severe famines in [[China]] and [[Egypt]] during the 12th and early 13th centuries, there was a black-market trade in corpses of little children that were roasted or boiled whole. |

|||

[[Lowell Thomas]] records the cannibalisation of some of the surviving crew members of the ''Dumaru'' after the ship exploded and sank during the [[First World War]] in his book, ''The Wreck of the Dumaru'' (1930). |

|||

In China, human-flesh sellers advertised such corpses as good for being boiled or steamed whole, "including their bones", and praised their particular tenderness.{{sfn|Chong|1990|p=137}}{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=260}} |

|||

In [[Cairo]], Egypt, the Arab physician [[Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi]] repeatedly saw "little children, roasted or boiled", offered for sale in baskets on street corners during a heavy famine that started in 1200 CE.{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|pp=47–51}} |

|||

Older children sometimes suffered the same fate: Once he saw "a child nearing the age of puberty, who had been found roasted"; two young people confessed to having killed and cooked the child.{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|p=50}} |

|||

In some cases children were roasted and offered for sale by their own parents; other victims were street children, who had become very numerous and were often kidnapped and cooked by people looking for food or extra income. Al-Latif states that "the guilty were rarely caught in the act, and only when they were careless."{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|pp=49–51}} |

|||

Documentary and forensic evidence supports eyewitness accounts of cannibalism by Japanese troops during World War II. This practice was resorted to when food ran out, with Japanese soldiers killing and eating each other when enemy civilians were not available. In other cases, enemy soldiers were executed and then dissected. A well-documented case occurred in Chichi Jima in 1945, when Japanese soldiers killed and ate eight downed American airmen. This case was investigated in 1947 in a war-crimes trial, and of 30 Japanese soldiers prosecuted, five (Maj. Matoba, Gen. Tachibana, Adm. Mori, Capt. Yoshii and Dr. Teraki) were found guilty and hanged. |

|||

The victims were so numerous that sometimes "two or three children, even more, would be found in a single cooking pot."{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|p=54}} |

|||

Al-Latif notes that, while initially people were shocked by such acts, they "eventually ... grew accustomed, and some conceived such a taste for these detestable meats that they made them their ordinary provender, eating them for enjoyment and ... [thinking] up a variety of preparation methods.... The horror people had felt at first vanished entirely; one spoke if it, and heard it spoken of, as a matter of everyday indifference."{{sfn|Tannahill|1975|p=49}} |

|||

[[File:Tartar cannibalism illumination Matthew Paris Chronica Majora.jpg|Depiction of [[Mongols|Mongol]] cannibalism from the ''[[Chronica Majora]]''|thumb|left|upright=1.15]] |

|||

When [[Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571]] crashed into the [[Andes]] on [[October 13]], [[1972]], the survivors resorted to eating the deceased during their 72 days in the mountains. Their story was later recounted in the books [[Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors]] and [[Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home|Miracle in the Andes]] as well as the film [[Alive (1993 film)|Alive]] by Frank Marshall and the documentary [[Alive: 20 Years Later]]. |

|||

After the end of the Mongol-led [[Yuan dynasty]] (1271–1368), a Chinese writer criticized in his recollections of the period that some [[Mongol]] soldiers ate human flesh because of its taste rather than (as had also occurred in other times) merely in cases of necessary. He added that they enjoyed torturing their victims (often children or women, whose flesh was preferred over that of men) by roasting them alive, in "large jars whose outside touched the fire [or] on an iron grate". |

|||

Other victims were placed "inside a double bag ... which was put into a large pot" and so boiled alive.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|p=270}} |

|||

While not mentioning live roasting or boiling, European authors also complained about cannibalism and cruelty during the [[Mongol invasion of Europe]], and a drawing in the ''[[Chronica Majora]]'' (compiled by [[Matthew Paris]]) shows Mongol fighters spit-roasting a human victim.{{sfn|Siefkes|2022|pp=270–271}}<ref>{{cite book |last= Andrea |first=Alfred J. |date=2020 |title=Medieval Record: Sources of Medieval History |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nznRDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA338 |publisher=Hackett |pages=338–339 |isbn=978-1-62466-870-8}}</ref> |

|||

{{interlanguage link|Pedro de Margarit|es}}, who accompanied [[Christopher Columbus]] during his [[Voyages of Christopher Columbus#Second voyage (1493–1496)|second voyage]], afterwards stated "that he saw there with his own eyes several Indians skewered on spits being roasted over burning coals as a treat for the gluttonous."<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Symcox |editor1-first=Geoffrey |editor2-last=Formisano |editor2-first=Luciano |title=Italian Reports on America, 1493–1522: Accounts by Contemporary Observers |date=2002 |publisher=Brepols |location=Turnhout |page=39}}</ref> |

|||

==Cannibalism as cultural libel== |

|||

[[Jean de Léry]], who lived for several months among the [[Tupinambá people|Tupinambá]] in Brazil, writes that several of his companions reported "that they had seen not only a number of men and women cut in pieces and grilled on the ''[[buccan|boucans]]'', but also little unweaned children roasted whole" after a successful attack on an enemy village.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Léry |first1=Jean de |title=History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America |date=1992 |publisher=University of California Press |location=Berkeley |page=130 |author-link1=Jean de Léry |title-link=History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil}}</ref> |

|||

{{seealso|Blood libel}} |

|||