Joyce Kilmer

Alfred Joyce Kilmer | |

|---|---|

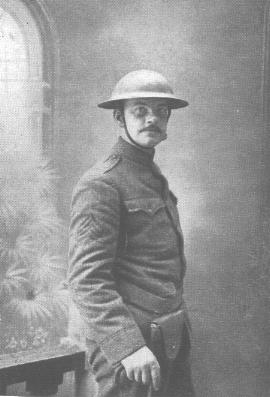

Sgt. Joyce Kilmer, as a member of the 69th Volunteer Infantry Unit, circa 1918. | |

| Born | 6 December 1886. New Brunswick, New Jersey (USA) |

| Died | 30 July 1918 near Seringes, France |

| Occupation | poet, journalist, editor, lecturer, soldier |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1909-1918 |

| Genre | poetry, literary criticism, catholicism |

| Signature | |

| |

Alfred Joyce Kilmer (6 December 1886 – 30 July 1918), known familiarly as Joyce Kilmer, was an American journalist, poet, literary critic, lecturer and editor. Though a prolific poet whose works celebrated the common beauty of the natural world as well as his religious faith, Kilmer is remembered most for a poem entitled "Trees" (1913) which was published in the collection Trees and Other Poems in 1914. At the time of his deployment to Europe during the first World War (1914-1918), Kilmer was considered the leading American Roman Catholic poet and lecturer of his generation whom critics often compared to British contemporaries G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936) and Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953). A sergeant in the famous 69th Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Kilmer was killed at the Second Battle of Marne in 1918 at the age of 31.

Biography

Early years: 1886-1908

Kilmer was born on 6 December 1886 in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the fourth and youngest child of Annie Ellen Kilburn (1849–1932) and Dr. Frederick Barnett Kilmer (1851–1934), a physician and chemist employed by the Johnson and Johnson Company and inventor of the company's famed Baby Powder.[1][2] He was named Alfred Joyce Kilmer after the Rev. Dr. Alfred Stowe and the Rev. Dr. Elisha Brooks Joyce, two consecutive rectors of Christ Church, the oldest episcopal parish in New Brunswick, where the Kilmer family were parishioners.[3] Rector Joyce, who served the parish from 1883 to 1916, (Stowe served from 1839 to 1883) baptised the young Kilmer.[4] Kilmer would later convert from the Anglican church to Roman Catholicism in 1913.

Kilmer's birthplace in New Brunswick, where the Kilmer family lived from 1886 to 1892, is still standing, and houses a small museum to Kilmer, as well as a few Middlesex County government offices.[5]

Kilmer entered the Rutgers College Grammar School (now Rutgers Preparatory School) in 1895 at the age of 8. During his years at the Grammar School, he...

- "...won the Lane prize in public speaking and was editor-in-chief of the Argo, the school paper. He loved the classics, although he had considerable difficulty with Greek. In his last year at Rutgers, he won the first Lane Classical Prize, a free scholarship for the academic course at Rutgers College, and one hundred dollars in money. Despite his difficulties with mathematics and Greek, he stood at the head of his class in preparatory school."[6]

After graduating from the Rutgers College Grammar School in 1904, he continued his education at Rutgers College from 1904 to 1906. At Rutgers, Kilmer was associate editor of the Targum, the campus newspaper and a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity. Unable to complete the rigorous mathematics requirement in the curriculum at Rutgers, facing a repeat of his sophomore year and under pressure from his mother, Kilmer transferred to Columbia University in New York City.[7]

At Columbia, Kilmer was vice-president of the Philolexian Society, associate editor of Columbia Spectator, the campus newspaper and was a member of the Debating Union. He completed his Bachelor of Arts (A.B.) degree and was graduated from Columbia on 23 May 1908.[8] Shortly after graduation, on 9 June 1908, he married Aline Murray (1888–1941), a fellow poet to whom he had been engaged since his sophomore year at Rutgers.[9] Five children were born to the marriage: Kenton Sinclair Kilmer (1909–1995), Michael Barry Kilmer (1916–1927), Deborah ("Sister Michael") Clanton Kilmer (1914–1999), Rose Kilburn Kilmer (1912–1917), and Christopher Kilmer (1917–1984).[10]

Years of writing and faith: 1909-1917

Shortly after his marriage and graduation from Columbia, Kilmer sought teaching positions. In the Autumn of 1908, Kilmer obtained a position teaching Latin in Morristown, New Jersey, and finding that teaching did not demand much of his time, he found considerable time to dedicate to writing. At this time, he submitted essays to Red Cross Notes (including his first published piece, an essay on the "Psychology of Advertising") and poems to Moods, Smart Set, The Sun, The Pathfinder and The Bang. In addition to all this, he wrote book reviews for The Literary Digest, Town & Country, The Nation, and The New York Times. By June 1909, Kilmer had abandoned any aspirations to continue teaching and relocated to New York City, the literary and publishing mecca of the United States, deciding to focus solely on a career as a writer.[11]

From 1909 to 1912, Kilmer was employed by Funk and Wagnalls which was preparing an edition of "The Standard Dictionary". According to Hillis,

- "[Kilmer's] job was to define ordinary words assigned to him at five cents for each word defined. This was a job at which one would ordinarily earn ten to twelve dollars a week, but Kilmer attacked the task with such vigor and speed that it was soon thought wisest to put him on a regular salary."[12]

Shortly after the publication of The Standard Dictionary in 1912, Kilmer became a special writer for the New York Times Review of Books]] and the New York Times Sunday Magazine and was often engaged in lecturing. Kilmer and his family then moved to Mahwah, New Jersey, where he resided until his service and death in World War I. Kilmer at this time was established as a published poet, and as a popular lecturer. According to Robert Holliday, Kilmer "frequently neglected to make any preparation for his speeches, not even choosing a subject until the beginning of the dinner which was to culminate in a specimen of his oratory. His constant research for the dictionary, and, later on, for his New York Times articles, must have given him a store of knowledge at his fingertips to be produced at a moment's notice for these emergencies."[13]

In 1911, Kilmer first book of verse, entitled Summer of Love was published. Kilmer would later write that "...some of the poems in it, those inspired by genuine love, are not things of which to be ashamed, and you, understanding, would not be offended by the others."

Shortly after the birth of the Kilmer's daughter Rose (1912–1917), she was stricken with infantile paralysis. The Kilmer's turned to their religious faith, and in correspondence between Joyce Kilmer and Father James J. Daly, Joyce and Aline began a conversion to Roman Catholicism into which church they were received in 1913. In one of these letters, Kilmer writes:

- "Of course you understand my conversion. I am beginning to understand it. I believed in the Catholic position, the Catholic view of ethics and aesthetics, for a long time. But I wanted something not intellectual, some conviction not mental - in fact I wanted Faith.

- "Just off Broadway, on the way from the Hudson Tube Station to the Times Building, there is a Church, called the Church of the Holy Innocents. Since it is in the heart of the Tenderloin, this name is strangely appropriate - for there surely is need of youth and innocence. Well, every morning for months I stopped on my way to the office and prayed in this Church for faith. When faith did come, it came, I think, by way of my little paralysed daughter. Her lifeless hands led me; I think her tiny feet know beautiful paths. You understand this and it gives me a selfish pleasure to write it down."[14]

The year 1913 approached Kilmer in trials of suffering and faith but also in success. With the publication of "Trees" in the magazine Poetry, Kilmer gained immense popularity as a poet across the United States. Also at this time, according to Robert Holliday, his popularity and success as a lecturer, particularly one seeking to reach a Catholic audience, "It is not an unsupported assertion to say that he was in his time and place the laureate of the Catholic Church." [15] "Trees" and other Kilmer poetry was published the following year, in Trees and Other Poems (1914). The next few years saw an immense output of work, continuing his lecturing, his literary criticism and essays, writing poetry, and finding the time in 1915 to become poetry editor of Current Literature and contributing editor of Warner's Library of the World's Best Literature. After the publication of The Circus and Other Essays in 1916, the following year would see the publication of three books, Literature in the Making (1917), Main Street and Other Poems (1917), and Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets (1917).

War years: 1917-1918

Within a few days after the United States declared war on Germany and entered the first World War in April 1917, Kilmer enlisted in the Seventh Regiment of the New York National Guard. In August, Kilmer was assigned, initially, as a statistician with the 69th Volunteer Infantry Regiment (better known as the "Fighting 69th" and later redesignated the 165th Infantry Regiment), of the 42nd "Rainbow" Division and quickly rose to the rank of Sergeant. Though he was eligible for commission as an officer and often recommended for such posts during the course of the war, Kilmer refused stating that he would rather be a sergeant in the Fighting 69th than an officer in any other regiment.[16]

In September, before Kilmer was deployed, the Kilmer family was met with both with the contrary emotions of tragedy and rejoicing. The Kilmer's daughter Rose had died, and twelve days later, their son Christopher was born.[17]. Kilmer sailed to Europe with his regiment on 31 October 1917, arriving in France two weeks later. Before his departure, Kilmer had contracted with publishers to write a book about the war, deciding upon the title Here and There with the Fighting Sixty-Ninth. Kilmer wrote home, stating "I haven't written anything in prose or verse since I got here - except statistics - but I've stored up a lot of memories to turn into copy when I get a chance."[18] Unfortunately, Kilmer never was to write such a book. During his time in Europe, Kilmer did write prose sketches and poetry, most notably the poem "Rouge Bouquet" which was written after the First Battalion of the 42nd Division, which had been occupying the Rouge Bouquet a forest northeast of the French village of Baccarat, which at the time was a quiet sector of the front—was struck by a heavy artillery bombardment on the afternoon of 12 March 1918 that buried 21 men of the unit, of which 14 remained entombed.[19][20][21]

Kilmer sought more hazardous duty and was transferred to the Regimental Intelligence Section, in April 1918. He wrote to his wife, Aline that, "Now I'm doing work I love - and work you may be proud of. None of the drudgery of soldiering, but a double share of glory and thrills." According to Hillis:

- Kilmer's companions wrote: "He was worshipped by the men about him. I have heard them speak with awe of his coolness and his nerve in scouting patrols in No Man's Land.” This coolness and his habit of choosing, with typical enthusiasm, the most dangerous and difficult missions, led to his death.[22]

During the Second Battle of Marne, there was heavy fighting throughout the last days of July 1918, and on 30 July 1918, Kilmer volunteered to accompany Major William "Wild Bill" Donovan when Donovan's First Battalion was sent to lead the day's attack.

During the course of the day, Kilmer led a scouting party to find the position of a German machine gun position. When his comrades found him, some time later, they thought at first that he was peering over the edge of a little hill, where he had crawled for a better view. When he did not answer their call, they ran to him and found him dead. According to Father Duffy wrote: “A bullet had pierced his brain. His body was carried in and buried by the side of Ames. God rest his dear and gallant soul.”[23] Kilmer died, likely immediately, from a sniper's bullet to the head near Muercy Farm, beside the Oureq River near the village of Seringes, in France, on 30 July 1918 at the age of 31. For his valour, Kilmer was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre (Cross of War) by the French Republic.

Kilmer was buried in the Oise-Aisne Cemetery, near Fere-en-Tardenois, Aisne, Picardy, France. Although Kilmer is buried in France in an American military cemetery, a cenotaph is located on the Kilmer family plot in Elmwood Cemetery, in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

In the 1940 film, The Fighting 69th directed by William Keighley and starring James Cagney, Kilmer is depicted as a minor character played by actor Jeffrey Lynn (1909–1995).

Works

- Summer of Love. (New York: Baker and Taylor, 1911).

- Trees and Other Poems. (New York: Doubleday Doran and Co., 1914).

- The Circus and Other Essays. (New York: Lawrence J. Gomme, 1916).

- Main Street and Other Poems. (New York: George H. Doran, 1917).

- The Courage of Enlightenment. An address delivered in Campion College, Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, to the members of the graduating class, 15 June 1917. (Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin: 1917).

- Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets. (ed. by Joyce Kilmer). (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1917).

- Literature in the Making by some of its Makers. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1917).

- Poems, Essays and Letters in Two Volumes. Robert Cortes Holliday (ed.). (Volume One: Memoir and Poems, Volume Two: Prose Works) (New York: George H. Doran, 1918 - published posthumously).

- The Circus and Other Essays and Fugitive Pieces. (New York: George H. Doran, 1921 - published posthumously).

"Trees"

Though a prolific poet, Joyce Kilmer is chiefly known for a poem entitled "Trees" published in a collection entitled Trees and Other Poems (1914) after debuting in Poetry magazine in August 1913. The poem was written on 2 February 1913, in the Kilmer home in Mahwah, New Jersey.[24] Other sources, which state is was written in Chicago, are unsubstantiated. "Trees" has been given several musical settings that were quite popular in the 1940s and 1950s, the most popular written by Oscar Rasbach in 1922, with renditions performed by Ernestine Schumann-Heink, John Charles Thomas, Nelson Eddy, Robert Merrill and Paul Robeson.

The belowstated is the original text written by Kilmer.

- I think that I shall never see

- A poem lovely as a tree.

- A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

- Against the earth's sweet flowing breast;

- A tree that looks at God all day,

- And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

- A tree that may in summer wear

- A nest of robins in her hair;

- Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

- Who intimately lives with rain.

- Poems are made by fools like me,

- But only God can make a tree.

There have been several variations on the text, including many parody texts substituted to mimic Kilmer's seemingly simple rhyme and meter. Of the often repeated parodies, the most known is "Song of the Open Road" by Ogden Nash (1902–1971) in which Nash wrote:

- I think that I shall never see

- A billboard lovely as a tree.

- Indeed, unless the billboards fall,

- I shall not see a tree at all.

Inspiration

According to Kilmer's son, Kenton, the poem—which was not inspired by any tree in particular but about trees in general—was written "...in an upstairs bedroom... which served as Mother's and Dad's bedroom and also as Dad's office.... The window looked out down a hill, on our well-wooded lawn - trees of many kinds, from mature trees to thin saplings: oaks, maples, black and white birches, and I don't know what else." [25] However, a 1915 interview with Kilmer "pointed out that while Kilmer might be widely known for his affection for trees, his affection was certainly not sentimental - the most distinguished feature of Kilmer's property was a colossal woodpile outside his home. The house stood in the middle of a forest and what lawn it possessed was obtained only after Kilmer had spent months of weekend toil in chopping down trees, pulling up stumps, and splitting logs. Kilmer's neighbors had difficulty in believing that a man who could do that could also be a poet."[26]

Many locations across the United States maintain legends that certain trees in their localities inspired Kilmer to write the poem. Most noted among them is the tradition in Kilmer's birthplace, New Brunswick, New Jersey, states that Kilmer wrote the poem "Trees" after a large white oak (Quercus alba) tree that was located on the outskirts of town on the campus of Cook College (now known as the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences), at Rutgers University.[27] This tree, estimated to be over three hundred years old, was so weakened by age and disease that it had to be removed in 1963.[28] Currently, sapplings grown from acorns of the historic tree are being grown at the site, throughout the Middlesex County area, and in major arborteums around the United States. The remains of the original Kilmer Oak are currently kept in storage at Rutgers University.[29][30]

Scansion and analysis

"Trees" is a poem comprised of twelve lines—with the exception of the eleventh line which possesses seven syllables—each line consists of eight syllables in strict iambic tetrameter. The poem's rhyme scheme is organized in a series of rhyming couplets rendered aa bb cc dd ee aa.

Despite its deceptive simiplicity in rhyme and meter, "Trees" is notable for its use of personification and anthropomorphic imagery: the tree of the poem, which Kilmer depicts as female, is depicted as pressing its mouth to the earth's breast, looking at God and raising its "leafy arms" to pray. The tree of the poem also is given human physical attributes, namely Kilmer's description of the tree possessing a "hungry mouth", arms, hair (in which Robins nest), and a bosom.

Criticism and influence

Joyce Kilmer is a poet whose reputation is staked largely on the widespread popularity of one poem, namely "Trees", and who because of an untimely and early death did not have the opportunity to develop from his early work into a more mature poet and expand the amount of material within the corpus of his work. Because "Trees" is often dismissed by critics and scholars as simple verse, much of Kilmer's work, especially his literary criticism, has slipped into obscurity and as a result is ignored. Only a very few of his poems have appear in anthologies, and with the exception of "Trees" and to a much lesser extent "Rouge Bouquet", even have obtained lasting widespread popularity.

The entire corpus of Kilmer's work appears before the birth of the modernist movement, especially before the influence of the Lost Generation. In the years after Kilmer's death, poetry entered new directions, driven by the works of T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) and Ezra Pound.

Joyce Kilmer is often criticized for poetry that does not break free of the traditional modes, rhyme and meter, or themes.

Influences on his work

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Early works were inspired by and imitative of, Swinburne, Ernest Dowson, Aubrey Beardsley, and W.B. Yeats.

- I have come to regard them with intense admiration. Patmore seems to me to be a greater poet than Francis Thompson. He has not the rich vocabulary, the decorative erudition, the Shelleyan enthusiasm, which distinguish the 'Sister Songs' and the 'Hound of Heaven,' but he has a classical simplicity, a restraint and sincerity which make his poems satisfying.

It was later through Patmore, Francis Thompson, and the Meynells, that he seems to have become interested in Catholicism.

Kilmer, in 1912 became literary editor of an Anglican weekly, The Churchman and did considerable research into 16th and 17th century Anglican poets and metaphysical or mystic poets, including George Herbert, Thomas Traherne, Robert Herrick, Bishop Coxe, and Robert Stephen Hawker, the Vicar of Morwenstow, "a coast life-guard in a cassock."

Influences on others and popular culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Notable places and things named for Kilmer

Several municipalities across the United States have named parks, schools and streets in honour of Joyce Kilmer, including his hometown of New Brunswick, New Jersey, which renamed the street on which he was born "Joyce Kilmer Avenue."

- Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest (3,800 acres/15km²) located in the Nantahala National Forest, near Robbinsville in Graham County, North Carolina was dedicated in Kilmer's memory on 10 July 1936.

- Camp Kilmer, opened in 1942 in what is now Edison, New Jersey, an embarcation center for soldiers going to the European theatre during World War II. Many of the original buildings remain, and it is now the location of the Livingston campus of Rutgers University where a library is named after him.

- The State of New Jersey and the New Jersey Turnpike Authority have named a rest area on the New Jersey Turnpike, located in East Brunswick Township after him.

- The Philolexian Society of Columbia University, a collegiate literary society of which Kilmer was Vice President, holds the annual Joyce Kilmer Memorial Bad Poetry Contest in his honor.

External links and other resources

Notes and citations

- ^ Certificate of Birth for Alfred Joyce Kilmer, 6 December 1886, on microfilm at the Archives of the State of New Jersey, 225 West State Street, Trenton, New Jersey.

- ^ Joyce Kilmer: FAQ and Fancies with Kilmer genealogical information, accessed 26 December 2006.

- ^ List of Missionaries and Rectors - Christ Church in New Brunswick, NJ accessed 17 August 2006.

- ^ Baptismal Records for Christ Church, New Brunswick, New Jersey.

- ^ Historic New Brunswick accessed 17 August 2006.

- ^ Hillis, John. Joyce Kilmer: A Bio-Bibliography. Master of Science (Library Science) Thesis. Catholic University of America. (Washington, DC: 1962).

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Certificate of Marriage for Aline Murray and Alfred Joyce Kilmer, 9 June 1908, on microfilm at the Archives of the State of New Jersey, 225 West State Street, Trenton, New Jersey. Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Joyce Kilmer: FAQ and Fancies with Kilmer genealogical information, accessed 26 December 2006.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Holliday, Robert Cortes (ed.). "Memoir" in Joyce Kilmer: Poems, Essays and Letters. 2 volumes. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918), 1:24.; Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Letter from Joyce Kilmer to Father James J. Daly, 9 January 1914.

- ^ Holliday, loc. cit.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Letter from Joyce Kilmer to Aline Kilmer, 24 November 1917.

- ^ World War I Diary of Joseph J. Jones Sr., accessed 27 December 2006.

- ^ The History of the Fighting 69th: Rouge Bouquet, accessed 27 December 2006.

- ^ Duffy, Francis Patrick. Father Duffy’s Story. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1919).

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ Duffy, op. cit.

- ^ Joyce Kilmer (1886 - 1918) - Author of Trees and Other Poems, which cites Kilmer, Kenton. Memories of my Father, Joyce Kilmer (Joyce Kilmer Centennial, 1993) ISBN 978-0963752406 . Accessed 25 December 2006.

- ^ Joyce Kilmer (1886 - 1918) - Author of Trees and Other Poems, which cites Kilmer, Kenton. Memories of my Father, Joyce Kilmer (Joyce Kilmer Centennial, 1993) ISBN 978-0963752406. Accessed 25 December 2006.

- ^ Hillis, op. cit.

- ^ What a Difference a Tree Makes citing Lax, Roer and Smith, Frederick. The Great Song Thesaurus. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). ISBN 0195054083. Accessed 25 December 2006.

- ^ The New York Times, 19 September 1963. Of note, in an article reporting the demise of the "Kilmer Oak" is a quote that "Rutgers said it could not prove that Kilmer...had been inspired by the oak." which further confirms this attribution is unsubstantiated and its dissemination within the realm of rumour and urban (or in this case, provincial) legend.

- ^ Kilmer Oak Tree: Highland Park (NJ) Environmental Commission, accessed 26 December 2006.

- ^ Press Release: "Cook Student Named New Jersey Cooperative Education and Internship Association Student of the Year" (13 June 2006), accessed 26 December 2006.

Books and printed materials

- Duffy, Francis Patrick. Father Duffy’s Story. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1919). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Hillis, John. Joyce Kilmer: A Bio-Bibliography. Master of Science (Library Science) Thesis. Catholic University of America. (Washington, DC: 1962). NO ISBN.

- Holliday, Robert Cortes (ed.). “Memoir,” in Joyce Kilmer: Poems, Essays and Letters, 2 volumes. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918), 1:17ff. NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Kilmer, Annie Kilburn. Whimsies, More Whimsies. (New York: Frye Publishing Co., 1929). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Kilmer, Annie Kilburn. Memories of My Son, Sergeant Joyce Kilmer. (New York: Brentano's, 1920). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Kilmer, Annie Kilburn. Leaves of My Life. (New York: Frye Publishing Co., 1925). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Kilmer, Kenton. Memories of my Father, Joyce Kilmer (Joyce Kilmer Centennial, 1993). ISBN 978-0963752406

External links

- Tribute page at Rising Dove (a site by his grand-daughter)

- Tribute Page at the University of Notre Dame

- A Tribute to Joyce Kilmer by a Kilmer biographer

- Works by Joyce Kilmer at Project Gutenberg

- Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest website

- Philolexian Society of Columbia University

- Reelyredd's Poetry Pagesaudio version of Trees(with Jimmy Stewart voice impression)

- 1886 births

- 1918 deaths

- American poets

- American World War I killed in action

- Catholic poets

- Columbia University alumni

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Croix de guerre recipients

- Knights of Columbus

- New Jersey writers

- People from New Brunswick, New Jersey

- Roman Catholic writers

- Rutgers University alumni

- United States Army soldiers