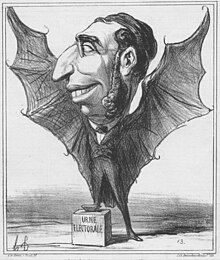

Émile Ollivier

Émile Ollivier (born July 2, 1825 in Marseille , † August 20, 1913 in Saint-Gervais-les-Bains ) was a French politician and statesman . Although he was originally a liberal, he came to terms with the politics of Emperor Napoleon III . In 1869/1870 he was a chairman of the French Council of Ministers. During the Spanish succession crisis, in July 1870, he joined those in the government who supported a declaration of war on Prussia. He was released before the fall of the Empire in September.

Political career

Member of Parliament in the Republic and the Empire

Ollivier's father, Demosthènes Ollivier (1799-1884), was a vehement opponent of the July monarchy of King Louis-Philippe I and was sent to the constituent assembly as a representative of Marseilles after the February Revolution of 1848 . After the end of the short-lived Second Republic with the coup d'état of Louis Napoléon on December 2, 1851, he was exiled and did not return to France until 1860. However, his influence on Ledru-Rollin during the republic gave his son Émile a post as general commissioner of the Bouches-du-Rhône department . The 23-year-old Ollivier had just been admitted to the Paris bar. His political views were less radical than those of his father; he put down a socialist uprising in Marseilles and recommended himself to General Cavaignac , who appointed him prefect of the département. A little later he was transferred to the relatively insignificant prefecture of Chaumont ( Département Haute-Marne ), a slight disparagement that may have been promoted by enemies of his father. He resigned from the public service to practice as a lawyer, which he did with success thanks to his outstanding skills.

Ollivier returned to politics in 1857 as a member of the 3rd arrondissement in the Seine department . He joined the constitutional opposition and, together with Alfred Darimon , Jules Favre , Jacques-Louis Hénon and Ernest Picard, formed a group that came to be known as Les Cinq (the Five), and which was able to win some concessions from Emperor Napoléon to a constitutional government. He welcomed the imperial decree of November 24 of the same year, which allowed parliamentary reports to be printed in the official bulletin Moniteur , and a replica of the Corps Législatif to the speech from the throne as the first steps in reform.

This consents changed Ollivier's attitude considerably. A year earlier, a violent attack against the imperial government, brought forward in the trial of Étienne Vacherot , who was charged with publishing the newspaper La Démocratie , resulted in a three-month suspension of his license to practice as a lawyer. Now he gradually turned away from his old allies, who rallied around Jules Favre, and during the session of 1866/1867 he formed a third party that pursued the idea of an Empire libéral (liberal empire) as an alternative to liberals and conservatives .

On the last day of December 1866, Count Walewski offered him the Ministry of Education, with the additional task of representing general government policy before the Chamber (there was no prime minister). He was continuing negotiations that Charles de Morny had started earlier. Ollivier did not want to be satisfied with the imperial decree of January 19, 1867 and the promise published in the Moniteur , which promised a relaxation of the press laws and concessions with regard to freedom of assembly , and therefore rejected the office. On the eve of the 1869 election, he published a policy statement, Le 19 janvier , in which he justified his policy. The sénatus-consulte (Senate decision) of September 8th gave the two houses normal parliamentary rights, and a little later the reactionary Eugène Rouher was dismissed. This paved the way for a responsible cabinet that was formed in the last week of 1869 and in which Ollivier was de facto, if not formally, prime minister.

Prime Minister 1869/1870

The new cabinet, also known as the January 2 Ministry, had difficult tasks ahead of it. The situation became even more complicated when Prince Pierre Bonaparte , cousin of Emperor Napoléon III, murdered the journalist Victor Noir on January 10th . Ollivier immediately called the Supreme Court to hear Bonaparte. The riots that followed his acquittal were bloodlessly put down; a circular prohibiting the prefects from putting pressure on the electors in favor of official candidates; the controversial Paris city planner Baron Haussmann , whose plans incurred boundless costs, was fired; the arrest of the prominent journalist Henri Rochefort put an end to heated press attacks against the emperor; on April 20, a sénatus-consulte was finally passed, with which the transition to a constitutional monarchy was achieved.

But neither concessions nor harshness could satisfy the “irreconcilable” in the opposition, who had directly influenced the electorate since the loosening of the press laws. Nevertheless, on the advice of Rouher, a plebiscite was held on May 8th on the amended constitution, from which the government emerged victorious with over 80 percent approval. The most prominent members of the left in Ollivier's cabinet - Louis-Joseph Buffet , Napoléon Daru and Talhouët Roy - resigned in April over the plebiscite. On May 15, 1870, Jacques Mège became Minister of Education (Ministre de l'Instruction publique) and Charles Plichon became Ministre des Travaux publics ; both were conservatives. Ollivier took over the duties of Foreign Minister Daru himself for a few weeks until the Duc de Gramont took his place. His doing and leaving contributed to the conclusion of the Ems dispatch and the declaration of war by Napoléon III. to Prussia on July 19, 1870.

Ollivier's plans were mixed up in the summer of 1870 when Leopold von Hohenzollern wanted to take over the throne in Spain . On Gramont's advice, the French ambassador to Prussia , Vincent Benedetti , was instructed to require the Prussian king to formally renounce the Hohenzollern candidacy for an unlimited period, which Wilhelm I refused. Ollivier let himself be won over to the war party. He probably could not have prevented the war for good, but he might have achieved a postponement if he had taken the time to hear Benedetti's own account of the outcome of his mission.

The North German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck anticipated him with a press release (" Emser Depesche "), whose presentation of the Ems conversation, which was unflattering for France, heated the French public opinion. On July 15, Ollivier rushed to appear before the Chamber and received a war loan of 500 million francs. He said there that he took responsibility for the war "lightly" (d'un cœur léger), since the war had been forced upon France. After the first French defeats in the Franco-Prussian War ( at Weißenburg (4th), at Spichern and at Wörth (both August 6th)) the Ollivier cabinet was dismissed on August 9th.

Third Republic

Ollivier fled to Italy and did not return to France until 1873. He continued the political struggle in the Bonapartist newspaper Estafette , but had no more political power and in 1880 clashed with Paul de Cassagnac in his own party .

Ollivier had many connections in the world of literature and the arts and was one of Richard Wagner's first advocates in Paris . He was accepted into the Académie française in 1870 , but never took office.

In retirement he wrote a history of L'Empire liberal , the first volume of which appeared in 1895. The work actually dealt with the distant and immediate causes of the war and was Ollivier's justification for his actions. In the 13th volume he showed that the blame for the disaster could not be blamed on him alone.

family

Émile Ollivier was married to Blandine Liszt († 1862), the eldest daughter of Franz Liszt and Marie d'Agoult .

Fonts

-

L'Empire Libéral

- Volume 1 (1895): le principe des Nationalités ( online )

- Volume 2 (1897): Louis-Napoléon et le coup d'état ( online )

- Volume 3 (1898): Napoléon III ( online )

- Volume 4 (1899): Napoléon III et Cavour ( online )

- Volume 5 (1900): L'Inauguration de l'Empire libérale roi Guillaume ( online )

- Volume 6: La Pologne; les élections de 1863, la loi des coalitions ( online )

- Volume 7 (1903): Le démembrement du Danemark; Le syllabus; La mort de Morny; L'entrevue de Biarritz ( online )

- Volume 8 (1903): L 'Année fatale - Sadowa (1866) ( online )

- Volume 9 (1904): Le Désarroi ( online )

- Volume 10 (1905): l 'Agonie de l' Empire autoritaire ( online )

- Volume 11 (1907): La veillée des armes. L'affaire Baudin. Preparation militaire prussienne. Le plan de Moltke. Réorganization de l'armée française par l'empereur et le maréchal Niel. Les élections en 1869. L'origine du complot Hohenzollern ( online )

- Volume 12 (1908): Le ministère du 2 janvier. Formation du ministère. L'affaire Victor Noir. Suite du complot Hohenzollern. ( online )

- Volume 13 (1909): Le guet-apens Hohenzollern. Le concile œcuménique. Le plébiscite ( online )

- Volume 14 (1909): La guerre. Explosion du complot Hohenzollern. Declaration you 6 juillet. Retrait de la candidature Hohenzollern. Demande de garantie. Soufflet de Bismarck. Notre réponse au soufflet de Bismarck. La déclaration de guerre ( online )

- Volume 15 (1911): Étions-nous prêts? Preparation. Mobilization. Sarrebruck. Alliances ( online )

- Volume 16 (1912): Le suicide. Premier acte: Woerth. Forbach. Renversement du ministère ( online )

- Volume 17 (1915): La fin ( online )

- Volume 18 (1918): Table générale et analytique ( online )

- Democratie et liberté (1867, [1] )

- Le Ministère du 2 janvier, mes discours (1875)

- Principes et conduite (1875)

- L'Eglise et l'Etat au concile du Vatican (2 vols., 1879)

- Solutions politiques et sociales (1893)

- Nouveau Manuel du droit ecclésiastique français (1885).

literature

- Lise Gauvin Ed .: Émile Ollivier. Un destin example. Mémoire d'Encrier, Montréal 2012

Web links

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

Footnotes

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Napoleon, Comte Daru |

Foreign Minister of France April 14, 1870 - May 15, 1870 |

Antoine Alfred Agénor de Gramont |

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Jean-Baptiste Duvergier |

Minister of Justice of France January 2, 1870 - August 10, 1870 |

Michel Grandperret |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ollivier, Émile |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French politician and statesman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 2, 1825 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Marseille , France |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 20, 1913 |

| Place of death | Saint-Gervais-les-Bains , France |