Altıntepe

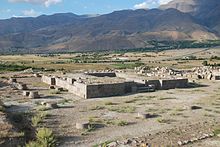

Altıntepe ( Turkish golden hill ) is the settlement hill of a fortified Urartean residence with a tower temple and well-preserved burial chambers from the second half of the 8th to the second half of the 7th century BC. The hill is located near Erzincan in the Anatolian highlands in eastern Turkey . The layout of the westernmost Urartian city was discovered in 1938, and the excavations from 1959 onwards revealed important finds from the heyday of the empire, especially bronze vessels and fragments of wall paintings. Altıntepe was settled from the Early Bronze Age to the Middle Ages.

location

Coordinates: 39 ° 41 ′ 47.6 " N , 39 ° 38 ′ 47.9" E

Altıntepe is located in the district of Üzümlü in the province of Erzincan , 20 kilometers east of the provincial capital on the northern edge of a wide plain through which the Karasu , a source river of the Euphrates , flows in a north-westerly direction . The 60 meter high frustoconical hill of volcanic origin can be seen north of the E80 motorway between Erzincan and Erzurum . Its summit reaches 1215 meters above sea level. The foot of the hill is 500 meters in diameter, a little more than the distance to the road. In the western area of the hill, as in the Urartian period, cattle and sheep graze on meadows that are criss-crossed by numerous irrigation channels, other small watercourses and swamps. The only access is therefore a road that branches off the highway and heads in an arc of about two kilometers from the north towards the hill.

In the direct vicinity of Altıntepe, two kilometers to the west as the crow flies, the Saztepe hill towering 40 meters from the plain with remains of Iron Age settlement belongs . The hill with a water pumping station at its top is also only accessible via a driveway from the main road. Opposite this junction is the small agricultural settlement Saztepe in the south of the highway. Between the two hills, a concrete factory and a brick factory produce on the main road. In this area, archaeologists found another 140 × 200 meter settlement mound 500 meters west of Altıntepe, which is called Küpesik Höyük after the name of a village nearby . It is not visible to the untrained eye. The swampy grassland must have been a species-rich animal enclosure ( Paradeisos ) in ancient times , mainly a gathering place for wild birds. Due to the construction of canals, the marshland has significantly decreased compared to then. The Paradeisos can be found on the floor mosaic of a church from the 6th century, which was uncovered on the lower east side of Altıntepe. Küçük Höyük is another hill in the north that lies in the middle of a stream.

To the east of Altıntepe, small parcels of arable land (sugar beet), vegetable gardens and rows of trees near small villages make soil investigation difficult. In the south, sandy alluvial land and floods near the Karasu disturb.

Research history

During the construction of the Erzincan-Erzurum railway line, workers are said to have discovered the first bronze vessels on Altıntepe in 1938. However, the railway line runs a few kilometers away and does not go over the hill. Therefore, another version is at least as plausible, according to which residents of a nearby village opened and looted one of the chamber tombs. In any case, some of the finds were sold to the Archaeological Museum in Ankara. In April 1938, Turkish newspapers in Istanbul and Ankara made the site known through illustrated articles. Hans Henning von der Osten published a report on his visit in 1939 and described the bronze finds from the open rock grave. In the following years treasure hunters were repeatedly active. In 1956, road workers broke open the northeast of the three burial chambers, leaving behind some of the grave goods. The first scientific excavations took place between 1959 and 1968 under Tahsin Özgüç from the University of Ankara . He concentrated his work on the castle and the main temples and living areas on the hill. At the end of the investigation, the excavation area was not filled in as a security measure, as is usually the case, but was left to its own devices and other predatory graves and gradually overgrown with grass.

A second excavation campaign began in 2003, led by Mehmet Karaosmanoğlu, also on behalf of Ankara University. The church on the east side of the hill was exposed. In addition to clarifying some unanswered questions from the previous excavations, especially in 2006 and 2007 the focus was on soil exploration of the surrounding area, on the economic relationships between the fortress and its satellite settlements or the temporary camps where cattle were kept within a radius of five kilometers to explore. The natural boundaries of the area are the foot of the mountains to the north and the Karasu River to the south.

The study area also includes the flat Küpesik Höyük, which over time disappeared into the plain consisting of soft, sandy-gravelly alluvial soils . The holes in the robbery graves, which are up to six meters deep, however, show a correspondingly far-reaching sequence of cultural layers.

In addition, an exploratory excavation was carried out in 2007 on the north-western edge of the fortress, during which a masonry made of mighty blocks came to light under a high layer of rubble from the Middle Ages, which is interpreted as a terrace.

Saztepe was first examined by Charles Burney in the mid-1950s, and in 1993 Geoffrey D. Summers reevaluated the material he found and dated the ceramic. He referred to a large part as Triangle Ware and assigned them to the post-Urartian, Achaemenid period. The building layer in Altıntepe, defined as phase II , also dated Summers to the Achaemenid period.

history

The oldest excavation finds date from the early Bronze Age. On the smaller neighboring hills, ceramics from the early Iron Age predominate, while on Saztepe, finds from the late Iron Age predominate, i.e. after the fall of the Urartian Empire.

Urartu is inscribed from the beginning of the 9th century BC. Known. Its capital was in the highlands of Van in southeastern Turkey. The largest area of the settlement area extended in the east to Lake Urmia and Sabalan , a mountain range in the Iranian province of East Azerbaijan , in the north to the mountains of northern Armenia and in the south it was bordered by Assyria .

Altıntepe was the westernmost settlement on the border with the Phrygian Empire. During the expansion under King Sarduri II (ruled around 760–730 BC) the area of power extended at least to this point. The temple complex was probably built in the 2nd half of the 8th century, the burial chambers are dated to the end of the 8th and beginning of the 7th century. An incised inscription mentions King Argišti II (r. 714–680). Little is known about his reign, except that he left some inscriptions in the most eastern places. Beginning of the 6th century BC The Urartian state collapsed in its heartland. It is not clear whether Altıntepe and the surrounding area were still inhabited by Urartian settlers at this time, or whether the pottery ( triangle ware ) found mainly on the Saztepe is due to the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire . It is clear that the residents of Altıntepe left around this time and took some of the movable goods with them.

The excavated church from the 6th century AD documents a settlement in the early Byzantine period , the upper levels of settlement extend into the late Middle Ages. The Urartian name of the fortress is not known.

Description of the plant

The summit of Altıntepe was surrounded by a ring of walls with bastions and gates that led to a large palace in the southern center. Its size shows that the settlement must have been a local administrative center. A large part of the hilltop north-west of the palace was filled with a walled temple area with a portico. Since the surrounding wall, which ran along the edge of the flat surface, cuts through some building plans on the north and east sides, it is likely to have been erected later, towards the end of the Urartean period, when the increasingly militarily unstable situation made fortification necessary. The basic rectangular shape of the bastions with entrances from the inside also suggest a Hellenistic period when the wall was built.

temple

Altıntepe owned the westernmost tower temple of the Urartian Empire, which, like all others, was dedicated to the high god Ḫaldi . A portico was built in front of the four outer walls of a rectangular courtyard , the roof of which was supported by six wooden columns on each side, a total of 20, whose stone bases were preserved. Judging by the diameter of the column bases, the Urartean wooden columns were 43 centimeters in diameter. On the flat roof, the spaces between the beams were filled with reeds and covered with a layer of rammed earth.

The tower temple (susi) stood a little to the rear in the longitudinal axis of the courtyard, its entrance was in the southeast. It was square and measured 14 meters on the outside with a wall thickness of 4.75 meters. On the inside and outside of the well-preserved base zone, the excavators prepared a curtain wall made of carefully hewn and seamlessly laid stone blocks in two rows. The walls above the foundation walls were made of clay bricks and are no longer preserved. They had corner risers according to the classic pattern . Two steps led up to the entrance, a hole was drilled into the stone blocks on both sides, into which lances were probably once inserted. In front of the back wall in the cella was a base for the statue of the gods. Numerous offerings in the form of vases and spearheads were found in the vicinity. Such temples, which look like a tower, seem to have existed in all Urartian cities.

The entrance to the temple courtyard was originally located opposite the temple facade in the middle of the south-east wall, but was no longer usable when the adjacent palace complex was built. At this point a rectangular low stone altar was uncovered. Between it and the southeast wall, most of the ivory objects found came to light during excavations. Three rooms were built along the entire length of the south-western wall. After the building of the palace, the entrance to the temple courtyard was presumably located in the outer wall of the central room, which is twice as large as the side room. Side rooms and the Tempelhof wall belong to the same construction phase and together resulted in a square basic plan with an edge length of 27 meters. A free-standing building with two rooms of different sizes west of the Tempelhof does not have to be from the same period. It can be used as a priestly apartment or treasury.

palace

The rectangular building complex from the second layer, oriented from southwest to northeast, was a little higher and bordered the Tempelhof at an acute angle. The large pillared hall ( Apadana ) measured 44 × 25 meters inside. Three pillars in each of the two rows supported a flat wooden roof. The column bases that have been preserved have the unusual diameter of 1.5 meters, so it would be possible that the columns were not made of wood, but of clay. The outer mud walls were also quite massive, at least three meters thick, they stood on a foundation made of large, rough stone blocks. There was only one entrance on the northeast corner.

Apart from Altıntepe, only Teišebai URU and Erebuni , both in Armenia, have preserved fragments of wall paintings. The hall walls were probably decorated with wall paintings from the first half of the 7th century up to an average height of 2.35 meters. The pictures were applied in al secco on a thin layer of plaster, consisting of a clay slurry with which the clay walls were covered . Pomegranates and rosettes were depicted in a frieze in all the rooms below. Horizontal fields in the middle of the wall contained winged sphinxes , sitting bulls, geometric patterns, palmettes and genii around a tree of life . A special motif shows a sequence of images 60 centimeters high with a lion watching a deer. Both stand under a tree with a blue trunk with red leaves. In the next scene with the same tree, the lion is about to eat the deer.

Similar to the Tempelhof, three storage rooms were built on the north-western long side. In one room there were eleven pithoi (storage jugs) in three rows on the floor, in the second room there were 60 pithoi in rows of ten. One of the three adjoining rooms in the southeast was cut off halfway during the construction of the later (Hellenistic?) City wall. The defensive wall made of rough stone blocks sloped slightly inwards.

Chamber graves

Outside the wall on the southern slope, the entrances to three chamber graves were hidden under a four-meter-high layer of earth and stones. In 1938 predatory graves opened the first grave cave, which consisted of a two meter high, northwest-southeast oriented corridor, which was widened by three consecutive chambers, in the walls of which rectangular niches were sunk. A cantilever vault formed the upper end . A 40-centimeter-high layer of large rubble stones provided the necessary bearing weight, which in turn was covered by a layer of rammed earth interspersed with smaller stones.

At the same time as grave 1, a platform called an open-air shrine with a clay floor on the slope is dated. A row of steles on the back of this flat surface indicates a cultic connection with the tomb. In front of this row of four unlabeled steles, a libation basin was uncovered. A jug, as it is depicted on a stone weight made of Toprakkale together with an altar, a person praying or offering sacrifices and a sacred tree , was used to pour the libation on the altar. Most of the time bloodless sacrifices were made at the altars in front of the temple entrances. The place of sacrifice in Altıntepe is the only one known for the connection between libations and the cult of the dead. Grave goods such as a candelabra with a tripod seem to have been used for the death ceremony and then placed in the grave.

Grave 2 is from a later time, as it blocks a previously created path to the first grave. An exit ( dromos ) to the tomb from the southeast led to a single rectangular chamber with two rows of niches on all three walls. Depressions in the bottom of the niches speak for urns with cremations placed in them. Such depressions were also found in other Urartian burial chambers. Cremations seem to have been common practice not only among the common population and soldiers, as was previously assumed, but also in all classes of the population. As with grave 1, the entrance was closed with a precisely fitting stone slab and another rough stone in front of it.

In the third grave a few meters to the west, three chambers were lined up, the direction of the third deviating slightly from the straight line to the southwest. The rear two contained stone sarcophagi. In the anteroom, the entrance of which was in the northeast, there was a large cauldron in the middle and inside it an ornate bronze belt, horse figures, harness, parts of a chariot and two bronze disks, one of which contains an engraving of a winged deity and, at an angle below it, a smaller winged horse. The belt bears a cuneiform script from the time of King Argišti II. A man was buried in the sarcophagus of the second chamber, who was naked, as is usual for a warrior. There were plenty of gold and silver buttons and an iron shield next to it. The sarcophagus in the third chamber contained the remains of a woman dressed in a pompous robe and numerous jewelry additions made of gold and precious stones. The room was furnished with a wooden table and bench; all things intended for use in the world beyond.

Buildings from Byzantine times

The Byzantine church halfway up on the east side of the hill was exposed from 2003. One meter thick foundation walls remained, which formed a rectangle with external dimensions of 19.6 × 11.3 meters. The roof of the three-aisled basilica supported three columns in each row. The semicircular apse within the straight east wall (orientation northeast) was surrounded on both sides by adjoining rooms ( pastophoria ). The mosaic floor of the nave, which is unique in Eastern Anatolia, was largely preserved. In addition to strictly geometric motifs, there are also floral motifs and animal figures. The walls were adorned with Christian saints, who were decorated with colored stones and broken glass. The layer of a medieval cemetery lay over the destroyed church. The mosaic is protected by a corrugated iron roof with mesh walls on all sides.

The north half of the palace was partially covered by a chapel with a semicircular apse protruding from the east wall, the remains of which were removed. Foundation walls from Byzantine times were preserved to the east outside the defensive wall.

Finds

In Altıntepe, the only Urartian inscriptions with Luwian hieroglyphs were found alongside a large number of cuneiform scripts. Due to the two incised inscriptions in Luwian hieroglyphs, which can be read on the bronzes from the burial chambers, it can be dated to the reign of Argišti II.

Ivory figures and bronze objects from Altıntepe are among the most important Urartian finds. A very well-preserved bronze cauldron, 51 centimeters high and 72 centimeters in diameter, which comes from the first chamber grave discovered in 1938, attracted attention. It is decorated with four bulls' heads on the edge and stands on a tripod with bull hooves. A similar cauldron was recovered from the burial site of the Phrygian king Midas in Gordion at around the same time . In addition, mixing jugs, quivers, furniture fittings and candelabras with tripods made of bronze came from this grave in 1938. Grave 2 contained fragments of silver belts decorated with geometric designs.

The ivory objects around the altar at the southeast portico of the palace all belonged to a throne, for example a seated lion and a deer with a tree. Other finds from there were shields, numerous helmets and arrow and bow tips. The very colorful wall paintings from the palace are a specialty.

The archaeological sites of Altıntepe, Karmir Blur and Değirmentepe near Patnos provide information about the jewelry of the Urartians . Altıntepe jewelry found in women's and men's graves consists of gold and silver buttons and precious stones. Apart from Değirmentepe, Altıntepe had the richest selection of gemstones in Eastern Anatolia. These include jewelry objects made of carnelian , jasper , agate , frit porcelain , faience , amber , soapstone and rock crystal .

From the 8th and 7th centuries BC BC Urartian belt plates made of bronze were found in several places. Only one copy from Altıntepe can be clearly dated, because a cuneiform script indicates that its owner was a contemporary of Argišti I. It shows winged centaurs , which resemble the bird men of Anipemza , only that the latter do not hold bows in their hands.

literature

- Mehmet Işikli: The Results of Surveys in the Environs of the Urartian Fortress of Altintepe in Erzincan, Eastern Anatolia. (Investigations of Public Settlement Areas and Observations on the Post-Urartian Period.) In: Paolo Matthiae, Frances Pinnock, Licia Romano (Eds.): Icaane. Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of the Archeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 2. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 265-277

- Cengiz Işik: New observations on the depiction of cult scenes on Urartian roller stamp seals. In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute. Volume 101. De Gruyter, Berlin 1986, pp. 1-22

- Thomas Alexander Sinclair: Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey. Vol. II. The Pindar Press, London 1989, pp. 430-434

Web links

- Altıntepe Kazısı Sitesine Hoş Geldiniz! altintepekazisi.com. Website of the excavation team around Mehmet Karaosmanoğlu (Turkish)

- A. Cem Erkman: Examinations of found human teeth near Altıntepe (Turkish) (PDF file; 323 kB)

- Tahsin Özgüç: Altintepe'de Urartu Mımarlik Eserlerı. (Turkish) (PDF file; 5.51 MB)

- S. Özel et al. a .: Archeogeophysical studies in Altıntepe Urartu Castle. International Earthquake Symposium Kocaeli 2007. Map on p. 3 (Turkish) (PDF file; 293 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz Steinherr: The Urartian bronzes from Altintepe. (PDF; 4.0 MB) In: Anatolia III, 1958, pp. 97-102

- ^ Hans Henning von der Osten : New Urartean bronzes from Erzincan. In: VI. International Congress of Archeology, 1939, pp. 225–229

- ↑ Mirjo Salvini: History and Culture of the Urartians. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 14f

- ^ Antonio Sagona, Paul Zimansky: Ancient Turkey. Routledge, London / New York 2009, p. 328

- ↑ Işikli, pp. 270f

- ^ Salvini, p. 136

- ↑ Astrid Nunn: The wall painting and the glazed wall decorations in the ancient Orient. In: Handbook of Oriental Studies. 7th department. The old orient. Section 2, volume 6. Brill, Leiden 1988, p. 137

- ↑ Işik, pp. 13-16, Salvini, p. 188

- ↑ Veli Sevin: A rock-cut columbarium from Van Kale and the Urartian cremation rite . In: Anadolu Araştırmaları . Istanbul 1982, p. 159–165 ( Online [PDF; 2.6 MB ]).

- ↑ Sinclair, pp. 431-433

- ↑ According to the information board on site

- ^ Sagona / Zimansky, p. 360

- ^ Tahsin Özgüç: Jewelery, Gold Votive Plaques and a Silver Belt from Altıntepe. In: Anatolian Studies , Vol. 33, (Special Number in Honor of the Seventy-Fifth Birthday of Dr. Richard Barnett) 1983, pp. 33–37, here p. 35

- ↑ RW Hamilton: The Decorated Bronze Strip from Gushchi . In: Anatolian Studies, Vol. 15, 1965, pp. 41–51, here p. 49