Luwian language

| Luwish | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

formerly in Anatolia , Northern Syria | |

| speaker | none ( language extinct ) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-3 | ||

Luwian was probably the most widely used Anatolian language . It was made in the 2nd and 1st millennium BC. Spoken in Anatolia . Luwisch is divided into the two dialects cuneiform Luwisch and hieroglyphic Luwisch , which use different writing systems.

In addition to the two Luwian dialects, the term Luwian languages also includes the languages Lycian , Carian , Pisidian and Sidetic , which are closely related to Luwian within the Anatolian languages . Of these languages, Luwian is the best documented and researched.

classification

The Luwian languages, together with Hittite , Palaic and Lydian, form the Anatolian languages, a language that dates back to the 1st millennium BC. Extinct branch of the Indo-European language family . Closest related to Luwian is Lycian; some linguists consider it possible that Lycian is even a direct successor or dialect of Luwian, others firmly reject this hypothesis. It is difficult to distinguish Luwian from Pisidic and Sidetic, two little-known languages, and it cannot be ruled out that these are later forms of Luwian. On the other hand, Carian is the only Luwian language that can be more clearly distinguished from the actual Luwian.

Luwisch has typical features of an older Indo-European language and is an inflected accusative language with some agglutinating elements. The morphology shows great similarities with the Hittite.

History and dissemination

In the 2nd millennium BC In BC Luwish was spoken in large parts of the Hittite Empire , mainly in south and south-west Anatolia ; Evidence of the language can also be found in the other areas of Anatolia and in northern Syria . An exact geographical delimitation of the language area is difficult and a reconstruction is practically only possible on the basis of the inscriptions found. This results in overlaps with the presumed Hittite language area. The exact position of the Luwian language within the Hittite empire is unclear. There was a linguistic exchange between Luwian and Hittite early on, which reached its peak in the 13th century. This influence is attested by numerous Luwian loanwords in Hittite.

The Luwian is still alive after the collapse of the Hittite Empire (around 1200 BC) until the 7th century BC. Chr. Attested. Some linguists even argue that in the late period of the Hethic Empire in the 13th century BC The Hittite was replaced by the Luwian as everyday language.

In 1995 a Luwian seal came to light during excavations in Troy . This find led to speculation that Luwish was also spoken in Troy; in this case, however, Troy would be isolated outside the previously assumed Luwian language area. It is likely, however, that there were closer contacts between the Luwians and Troy.

Script and dialects

The Luwian language is divided into several dialects, which were recorded in two different writing systems: on the one hand the cuneiform Luwian in the old Babylonian cuneiform adapted for Hittite , on the other hand the hieroglyphic Luwian in the so-called Luwian hieroglyphic script . The differences between the dialects are minimal, affecting vocabulary, style and grammar. The different orthography of the two writing systems, however, hides certain differences. Other dialects that are counted as Luwian are Ištanuwisch and - possibly a closely related sister language - the language of Arzawa .

Cuneiform Luwish

Cuneiform Luwish was used by Hittite scribes, who used the cuneiform script common for Hittite and the associated writing conventions. In contrast to the Hittite, logograms , i.e. characters with a certain symbolic value, are less common. Above all, the syllable characters of the cuneiform are used. These are of the type V, VK or KV (V = vowel, K = consonant). A noticeable feature is the plene spelling of extended vowels, also at the beginning of a word. For this purpose, the vowel is repeated in the script, for example ii-ti (instead of i-ti ) for īdi “he goes” or a-an-ta (instead of an-ta ) for ānda “in / into”.

Hieroglyphics Luwish

Hieroglyphic Luwish was written in a hieroglyphic script that - unlike cuneiform script - was invented for the Luwian language. The font, which comprises a total of around 350 characters, consists of both logograms and syllable characters, whereby the logograms are primary and only then have the syllable characters developed from them. This can be seen, for example, in the tarri "three" logogram , from which the syllable tara / i developed. In addition to a few characters of the form KVKV, only syllable characters for V or KV appear. In contrast to the cuneiform Luwian, no plene spelling is used, but additional vowel symbols can be used for aesthetic reasons.

![]()

The use of logograms and syllable characters results in different ways of writing a word (as in other comparable writing systems, for example the Sumerian cuneiform or the Egyptian hieroglyphs ), shown here using the example of the Luwian word for “cow” (in the nominative singular). In transliteration, logograms are usually represented with a Latin term in capital letters, in this case with “bos”, the gender-neutral Latin term for “cattle”.

-

BOS - only with logogram

BOS - only with logogram -

wa / i-wa / i-sa - only in syllabary

wa / i-wa / i-sa - only in syllabary -

BOS-wa / i-sa - logogram with phonetic complement , which clarifies the pronunciation of the logogram

BOS-wa / i-sa - logogram with phonetic complement , which clarifies the pronunciation of the logogram -

(BOS) wa / i-wa / i-sa - syllabary with a preceding logogram, which acts as a determinative and shows that the name of a cow follows

(BOS) wa / i-wa / i-sa - syllabary with a preceding logogram, which acts as a determinative and shows that the name of a cow follows

A special word separator ![]() can be used to identify the beginning of a word , but its use is optional and inconsistent even within individual texts. Logograms can (as in Egyptian ) be

can be used to identify the beginning of a word , but its use is optional and inconsistent even within individual texts. Logograms can (as in Egyptian ) be ![]() distinguished from the syllable characters by a special logogram marker , but this distinction is only made sporadically.

distinguished from the syllable characters by a special logogram marker , but this distinction is only made sporadically.

The writing direction of the font is not clearly defined. Left-to-right and right-to-left writing are just as possible as the bus trophy , i.e. the direction changes with each line. The alignment of the characters follows the direction of writing. For aesthetic reasons, the order of characters may also be reversed.

In hieroglyphic writing, an n is not expressed before other consonants. For example, the spelling a-mi-za stands for aminza . The consonant r has a special position: only the syllable ru has its own character; the other characters containing r are formed by modifying other syllable characters by adding a slash to them. For example, the syllable tu becomes tura or turi . Syllable signs for Ka and Ki often match: for example, the sign wa can also stand for wi . In the course of the development of the font, however, new characters were created for some syllables, which also distinguish a - and i -vocalization: by underlining a character twice, it becomes clear that it is of the form Ka , with the non-underlined character form then only the value Ki retains, for example za versus zi .

![]()

![]()

The font is contained in Unicode in the block Anatolian hieroglyphs and is therefore standardized for use on computer systems.

History of science

Luwian in the form of the cuneiform Luwian was recognized by Emil Forrer as an independent but related language as early as 1919 when he deciphered Hittite . Further great advances in the study of the language came after the Second World War with the publication and analysis of a large number of texts; this includes works by Bernhard Rosenkranz, Heinrich Otten and Emmanuel Laroche . An important impulse came from Frank Starke in 1985 with the reorganization of the text corpus.

The decipherment and classification of the hieroglyphic Luwian caused much greater difficulties. In the 1920s, various attempts failed, in the 30s the correct assignment of individual logograms and syllable characters succeeded. At that time there was still no agreement on the classification of the language, but it was regarded as a form of Hittite and consequently referred to as Hieroglyphic Hittite . After an interruption of research activities during the Second World War, the decisive breakthrough came in 1947 with the discovery and publication of a Phoenician- hieroglyphic Luwian bilingualism by Helmuth Theodor Bossert . According to today's understanding, the reading of many syllable characters remained incorrect, and so the close relationship between the two Luwian dialects was not yet recognized.

In the 1970s, after a thorough revision of the reading of many hieroglyphs by John David Hawkins , Anna Morpurgo Davies and Günter Neumann, it became clear that the hieroglyphic Luwian was a dialect closely related to the cuneiform Luwian. Curiously, this revision goes back to a find outside the settlement area of the Luwians, namely to measurements of Urartian vessels, which were written in hieroglyphic Luwian script, but in Urartian language : the sound value za could be assigned to the sign previously read as ī , what started a chain reaction and resulted in a whole new series of readings. Since then, research has focused on working out the similarities between the two Luwian dialects, which has led to a much better understanding of Luwian.

![]()

Phonology

The reconstruction of the Luwian phoneme is mainly based on the written tradition and on comparisons with known Indo-European language developments.

The following table shows a minimal set of consonants that can be reconstructed from the script. The existence of further consonants, which are not differentiated in the script, is possible. The pharyngeal fricatives ħ and ʕ represent a possibility of how -h- and -hh- could be represented, as well as velar fricatives x and ɣ would be conceivable. In cuneiform Luwian transliteration, š is traditionally differentiated from an s , since it was originally different characters for two different sounds; in Luwian the characters probably represent the same sound s .

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar | palatal | velar |

phase- ryngal |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | stl. | sth. | |

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | k | G | ||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||||||

| Vibrants | r | |||||||||||

| Fricatives | s | z | H | ʕ | ||||||||

| Approximants | j | |||||||||||

| lateral approximants | w | l | ||||||||||

Luwian only knows three vowels, namely a , i and u , which appear briefly or elongated. However, different lengths do not distinguish the meaning, but are related to the stress and word order. For example, annan appears independently as an adverb ānnan "under" or as a preposition annān pātanza "under the feet".

In terms of phonetic developments in Luwian, Rhotazism is worth mentioning: seldom d , l and n can become r , for example īdi “he goes” to īri or wala- “to die” to wara- . In addition, a d can be lost at the end of a word and an s can be inserted between two dental consonants , * ad-tuwari becomes aztuwari "you eat" ( ds and z are phonetically equivalent).

grammar

Nominal morphology

A distinction is made between two genders: animate or communal (commune, utrum ) and inanimate or neuter (neutral, neuter ). There are two numbers: singular and plural; some animate nouns can form a collective plural in addition to the pure counting plural. Luwian knows six different cases: nominative , genitive , dative - locative , accusative , ablative - instrumental and vocative . In terms of their function, nominative, genitive, dative and accusative essentially correspond to those that they use in German. The ablative instrumental is used to indicate means and ends. The vocative as a salutation case occurs rarely and only in the singular.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative communis | -s | -anzi, -inzi |

| Accusative communis | -n, -an | |

| Nominative / accusative neuter | -Ø, -n | -a, -aya |

| Genitive | -s, -si | - |

| Dative-locative | -i, -iya, -a | -anza |

| Ablative instrumental | -ati | |

In the genus commune there is an additional -i- between the root and the case ending . In hieroglyphic Luwian the ending of nominative / accusative neuter is supplemented by a particle -sa / -za . In the genitive case, cuneiform Luwish and hieroglyphic Luwish differ more from each other. Only the hieroglyphic Luwian has a case ending for the genitive. In cuneiform Luwian, the genitive has to be replaced by a reference adjective. To do this, an adjective word formation morpheme is added to the stem of the noun and the new word declined like an adjective. This construction is also possible in hieroglyphic Luwian, where it can even occur in combination with the genitive ending.

Adjectives

| case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative communis | -asis | -asinzi |

| Accusative communis | -asin | |

| Nominative / accusative neuter | -asanza | -asa |

| Dative-locative | -asan | -asanza |

| Ablative instrumental | -asati | |

Adjectives match their reference word in number and gender. Forms for nominative and accusative are only differentiated for the genus commune, and there only in the singular. For the sake of clarity, only the word endings beginning with -a are shown in the table ; depending on the root of the word, -a can also become -i . The forms are based mainly on the forms of the noun declension, with an -as- occurring before the case ending that would be expected with a noun.

Pronouns

Luwian has the personal pronouns typical of Anatolian languages as well as demonstrative pronouns based on apa and za / zi . The declension is similar to that in Hittite, but not all cases are attested for the personal pronoun. In the 3rd person, the demonstrative pronoun apa- takes the place of the personal pronoun .

| Personal pronouns | possessive pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| independent | enclitic | independent | ||

| Singular | 1st person | amu , mu | -mu , -mi | ama- |

| 2nd person | tu , ti | -tu , -ti | tuwa- | |

| 3rd person | ( apa- ) | -as , -ata , -an , -du | apasa- | |

| Plural | 1st person | anza , anza | -anza | anza- |

| 2nd person | unzas , unza | -manza | unza- | |

| 3rd person | ( apa- ) | -ata , -manza | apasa- | |

Possessive pronouns and the demonstrative pronoun on apa- are declined like adjectives; The known forms of the personal pronouns are given, although the different use of the various personal pronouns is not entirely clear, nor is the distinction between different cases.

In addition to the forms shown in the table, Luwian has a demonstrative pronoun from the stem za- / zi- , of which not all case forms are known, and the regularly declined relative and interrogative pronouns kwis (nom. Sing. Com .), Kwin ( Akk. Sing. Com .), Kwinzi (Nom./Akk. Plur. Com.), Kwati (Dat./Abl. Sing.), Kwanza (Nom./Akk. Plur. Neut.), Kwaya . Some indefinite pronouns with a meaning that is not yet completely clear have also been handed down.

Verbal morphology

As is customary in Indo-European languages, Luwian distinguishes between two numbers: singular and plural, as well as three persons. There are two modes: indicative and imperative, but no subjunctive. Only active forms are known so far, but the existence of a medio-passive is suspected. A distinction is made between two tenses: present tense and past tense; the present tense also takes on the function of the future.

| Present | preterite | imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1st person | -wi | -Ha | - |

| 2nd person | -si | -ta | O | |

| 3rd person | -ti (r) | -ta (r) | -door) | |

| Plural | 1st person | -mina | -hana | - |

| 2nd person | -tani | -tan | -tanu | |

| 3rd person | -nti | -nta | -ntu | |

The conjugation is very similar to the Hittite ḫḫi conjugation . In the present indicative, there are also forms in -tisa for the 2nd person singular and forms in -i and -ia for the 3rd person singular .

A single participle can be formed with the suffix -a (i) mma . It has passive meaning for transitive verbs and static meaning for intransitive verbs. The infinitive ends in -una .

syntax

The usual word order is subject-object-verb , but to emphasize words or parts of sentences they can be placed at the beginning. Relative clauses are usually placed in front of the main clause, but the reverse order is also possible. Dependent reference words or adjectives usually come before the word they refer to.

Various conjunctions with temporal or conditional meaning serve to coordinate the subordinate clauses. There is no associative conjunction; However, main clauses can be coordinated by enclitic -ha , which is appended to the first word of the following sentence. In narratives, sentences are connected with predictive conjunctions : a- , added before the first word of the sentence, is to be understood as "and then"; pā as an independent conjunction at the beginning of a sentence or enclitic -pa indicate opposition or a change of subject in the story.

Vocabulary and texts

The well-known Luwian vocabulary consists for the most part of the purely Indo-European hereditary vocabulary. Foreign words for various technical and religious areas come mainly from Hurrian , although these were later adopted into the Hittite language via Luwian.

The surviving text corpus of the Luwian consists mainly of cuneiform ritual texts from the 16th and 15th centuries BC. Chr. And hieroglyphic monumental inscriptions together. There are also some letters and business documents. Most hieroglyphic inscriptions date from the 12th to 7th centuries BC. BC, i.e. from the time after the collapse of the Hittite empire.

Further written evidence are hieroglyphic Luwian seals from the 16th century to the 7th century. Seals from the time of the Hittite Empire are often written digraphically , both in Luwian hieroglyphs and in cuneiform. However, practically only logograms are used on the seals. The lack of syllables makes it impossible to draw any conclusions about the pronunciation of the names and titles mentioned on the seals, i.e. also a reliable assignment to one of the different languages.

Didactics of the Luwian

The study of the Luwian language falls into the area of the subject Hittitology or Ancient Anatolian Studies , which is mostly represented at German-speaking universities by the subjects Ancient Oriental and Indo-European Studies , which give introductions to the Luwian language at irregular intervals. Knowledge of cuneiform and Hittite is usually required in ancient oriental studies . In addition, representatives of Near Eastern archeology , epigraphy , ancient history , palaeography and religious history are interested in the language, archeology, history, culture and religion of the Luwians.

Text example

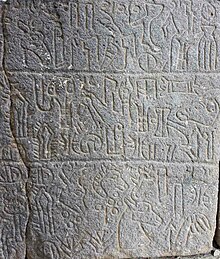

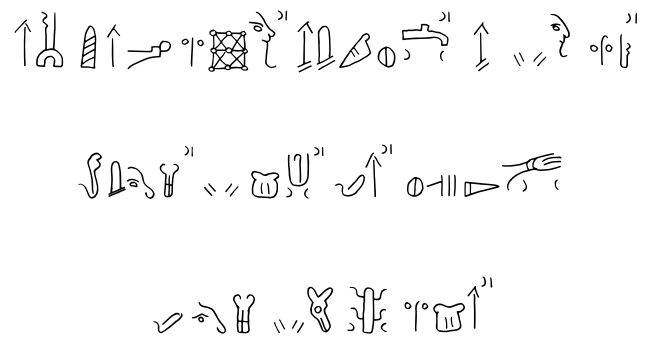

The text example comes from the Phoenician-hieroglyphic Luwian bilingualism of Karatepe . These hieroglyphs can be read from right to left. Various typical features of the hieroglyphic Luwian emerge:

- The characters are aligned from right to left according to the direction of writing.

- The lines are centered; emphasis is placed on an overall aesthetic appearance of the text.

- The beginning of a new word is only

indicated irregularly by .

indicated irregularly by . - Logograms are sometimes ( THIS in the first line) but not always ( URBS also in the first line) with the logogram markers

.

. - There are different spellings for the same words; tawiyan as VERSUS-na as well as VERSUS-ia-na , with the na symbol also being varied.

Redrawing:

| Transliteration | a 3 -wa / i | a 2 -mi-za | (THIS) ha-li-ia-za | a 3 -tana-wa / i-ni 2 -zi (URBS) | FINES-zi |

| analysis | a + wa | am-inza | haliy-anza | Adana + wann-inzi | irh-inzi |

| grammar | Conjunction + direct speech | "My" 1st Sg. Poss. Locomotive. | "Days" locomotive. Pl. | "Adana" + adjectivator, acc. Pl. | "Borders" acc. Pl. |

| Transliteration | (MANUS) la-tara / i-ha | zi-na | OCCIDENS-pa-mi | VERSUS-ia-na |

| analysis | ladara-ha | zina | ipam-i | tawiyan |

| grammar | "expand" 1st Sg. Prät. | "on the one hand"(*) | "West" locomotive. Sg. | "Direction" post position |

| Transliteration | zi-pa-wa / i | ORIENS-ta-mi | VERSUS-na |

| analysis | interest + pa + wa | isatam-i | tawiyan |

| grammar | “On the other hand” (*) + “but” + direct speech | "East" locomotive. Sg. | "Direction" post position |

* zin (a) is actually the adverb "here", which is derived from the demonstrative pronoun za- / zi- ; in the connection zin (a) ... zin (a) ... it takes on the function of a conjunction, which in German is best rendered as "on the one hand ... on the other hand ...".

Translation:

"In my day, I expanded the Adanic area on the one hand to the west, but on the other hand also to the east."

See also

literature

- John David Hawkins, Anna Morpurgo-Davies, Günter Neumann: Hittite hieroglyphs and Luwian. New evidence for the connection (= news from the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class . 1973, No. 6). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1973, ISBN 3-525-85116-2 .

- John David Hawkins: Inscriptions of the Iron Age (= Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions Vol. 1 = Studies on Indo-European Linguistics and Cultural Studies NF 8, 1). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York NY 2000, ISBN 3-11-010864-X .

- Massimiliano Marazzi: Il geroglifico anatolico. Problemi di analisi e prospettive di ricerca (= Biblioteca di ricerche linguistiche e filologiche 24). Herder, Rome 1990, ISBN 88-85134-23-8 .

- H. Craig Melchert: Anatolian Hieroglyphs. In: Peter T. Daniels, William Bright: The world's writing systems. Oxford University Press, New York NY / Oxford 1996, ISBN 0-19-507993-0 , pp. 120-124, online (PDF; 81 kB) .

- H. Craig Melchert (Ed.): The Luwians (= Handbook of oriental Studies . Sect. 1: The Near and Middle East. Vol. 68). Brill, Leiden et al. 2003, ISBN 90-04-13009-8 .

- H. Craig Melchert: Luvian. In: Roger D. Woodard (Ed.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, ISBN 0-521-56256-2 , pp. 576-584.

- H. Craig Melchert: Cuneiform Luvian Lexicon (= Lexica Anatolica 2). Melchert, Chapel-Hill 1993.

- Reinhold Plöchl: Introduction to Hieroglyphic Luwian (= Dresden Contributions to Hethitology. Vol. 8 Instrumenta ). Verlag der TU Dresden, Dresden 2003, ISBN 3-86005-351-5 .

- Annick Payne: Hieroglyphic Luwian. An Introduction with Original Texts (= Subsidia et instrumenta linguarum Orientis 2). 2nd revised edition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-447-06109-4 .

- Elisabeth Rieken : Hittite. In: Michael P. Streck (Ed.): Languages of the Old Orient. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-17996-X , pp. 80–127.

- Frank Starke : The cuneiform Luwian texts in transcription (= studies on the Boğazköy texts. Vol. 30). Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-447-02349-X .

- Luwian Identities: Culture, Language and Religion between Anatolia and the Aegean . Brill, 2013. ISBN 978-90-04-25279-0 (Hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25341-4 (e-book)

Web links

- Digital etymological-philological Dictionary of the Ancient Anatolian Corpus Languages (eDiAna) . Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich . Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- List of Luwian hieroglyphs (pdf; 244 kB)

- extensive list of words Luwisch-Englisch by H. Craig Melchert, 1993 (pdf; 2.13 MB)

- Text corpus of the cuneiform Luwischen, H. Craig Melchert, 2001 (pdf; 1.34 MB)

- Ancient writings: Luwian hieroglyphs

- Luwian (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Trevor R. Bryce : The Kingdom of the Hittites. , Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-928132-7

- ↑ Frank Starke: Troy in the context of the historical, political and linguistic environment of Asia Minor in the 2nd millennium. in Studia Troica Vol. 7, 1997 p. 457

- ^ H. Craig Melchert: Language. In: H. Craig Melchert (Ed.): The Luwians. Brill, Boston 2003, ISBN 90-04-13009-8

- ^ Manfred Korfmann: Troy in the light of the new research results. (PDF; 2.7 MB) Trier 2003, p. 40. ISSN 1611-9754

- ^ John Hawkins, A. Morpurgo Davies, Günter Neumann: Hittite hieroglyphs and Luwian, new evidence for the connection. In: News of the Academy of Sciences. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1973, 6, pp. 146-197. ISSN 0065-5287