Amatl

Amatl ( Spanish : amate from Nahuatl : āmatl) is a type of paper that was made in Mexico as far back as pre- Hispanic times . Amatl paper was produced on a large scale during the Aztec Triple Alliance and was used for communication, record keeping and rites; however, after the Spanish conquest of Mexico , its production was largely banned and replaced by European paper. The making of Amatl paper never died completely from nor the rituals associated with it. It remained widespread in the rugged, often inaccessible mountain regions of the northern Puebla and northern Veracruz states, with the small village of San Pablito in Puebla being known for the production of paper with "magical" properties by its shamans . This ritual use of paper took off in the middle of the 20th century. attracted the attention of foreign academics, which in turn drew the attention of the Otomí people of the region to the commercial opportunities of paper. They began selling it in major cities such as Mexico City , where the paper was used by Nahua Guerrero painters to create "new" local crafts, which the Mexican government then promoted.

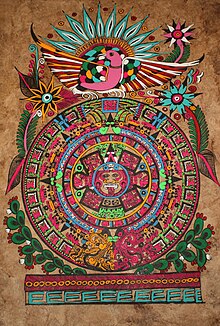

As a result of this and other innovations, Amatl paper is one of the Mexican local handicrafts available almost everywhere and sold both nationally and internationally. The Nahua paintings of the paper, also called "Amatl", attract a lot of attention , but Otomi paper makers have drawn attention not only because of the paper, but also because of the handicrafts that are created with it, such as elaborate cuts.

history

Amatl paper has a long history. This story exists not only because the raw materials are still there, but also because the craft, distribution and uses have been adapted to the needs and constraints of different eras. This history can be roughly divided into three periods: the pre- Hispanic times, the Spanish colonial times up to the 20th century and from the end of the 20th century to the present day, each characterized by the use of paper as a commodity.

Pre-Hispanic time

The development of paper in Mesoamerica shows parallels to the cultures in China and ancient Egypt , where rice fibers and papyrus were used. It is unknown where and when papermaking began in Mesoamerica. Some scholars give a date between 500 and 1000 AD, while others suggest it much earlier: at least before 300 AD.

Iconographies (in stone) from this period are provided with drawings that presumably show the manufacture of paper. For example, Monument 52 of the Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán illustrates a person who is adorned with pennants made of folded paper.

However, there is no more detailed information about papermaking from the pre-Hispanic times. Stone Dutchmen dating from the 6th century AD have been found and these tools are mostly found where Amatl trees ( Ficus cotinifolia was most popular, Ficus pertusa (Syn .: Ficus padifolia ), Ficus) citrifolia (Syn .: Ficus laevigata ), Ficus lapathifolia , Ficus maxima (Syn .: Ficus mexicana ) (Syn .: Ficus radula ), Ficus crocata (Syn .: Ficus yucatanensis ), Ficus obtusifolia (Syn .: Ficus bonplandiana ) (Syn .: Ficus involuta ) as well as Ficus glabrata (Syn .: Ficus insipidia ) and Ficus petiolaris , from the genus of figs and white mulberry Morus alba , black mulberry Morus nigra , red mulberry Morus rubra ) grow.

Most Dutch are made of volcanic rock , but some are also made of marble and granite . They are usually rectangular or circular with flutes on one or both sides to macerate the fibers . Such dutchers were always used by the Otomí artisans and were made entirely of volcanic rock with additional grooves on one side to hold the stone in place. According to some Spanish records, the tree bark was placed in water overnight so that it could soak up. The finer inner fibers were then separated from the coarser outer fibers and tapped into flat sheets. But you don't know who did the work or how the work was divided .

Paper also had a sacred aspect and was used in rituals together with other objects such as B. incense or incense, copal , Maguey thorns and rubber used. Tree bark paper was used in various ways for ceremonial and religious events: as decorations for fertility rituals, yiataztli , a kind of bag, and as an amatltéuitl , a badge that symbolized the soul of a prisoner after sacrifice. It has also been used to idols (idols), Priest and Victim candidates to dress in the form of crowns, stoles, feathers, wigs, belts and bracelets. Paper items such as flags, skeletons, and very long paper (the size of a person) were used as gifts, often by burning them. Another important paper item for rituals was paper, cut in the shape of long flags or trapezoids and painted with black rubber stains to mark the character of the god to be worshiped. At certain times of the year, they were also used to solicit rain. The paper was dyed blue with a plumage on the tip of the spear .

Maya

Debate from the 1940s through the 1970s has centered around AD 300 on the use of tree bark clothing among the Maya . Ethnolinguistic studies lead to the names of two villages in the Maya area, the reference to the use of tree bark paper have: Excachaché (place where white bark collars are smoothed) and Yokzachuún (over the white paper). The anthropologist Marion mentions that in Lacandones , in Chiapas , the Maya were still making and using tree bark clothing in the 1980s. For these reasons, it was probably the Maya who first propagated knowledge of the manufacture of tree bark paper (the Mayans called their paper "Huun") by using them throughout southern Mexico, Guatemala , Belize , Honduras and El Salvador widespread, in the heyday of the pre-classical period According to the researcher Hans Lenz, this Maya paper (Huun) was almost certainly not the Amatl paper that was known in later Mesoamerica. The difference is actually only in the surface treatment, the Aztecs improved Mayan paper by using heated stones to press the paper and thus closing the pores of the base paper, this corresponds to satinizing in modern paper production .

Aztecs

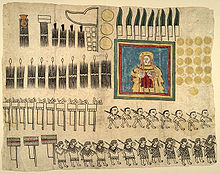

Amatl paper was used extensively during the Aztec Empire . This paper was produced in over 40 villages in the Aztec-controlled territory and then given as a tribute by the conquered peoples. The tribute was approximately 480,000 sheets annually. Most of the production was concentrated in what is now Morelos state , where ficus trees grow in abundance because of the climate. This paper was assigned to the royal sector to serve as gifts on special occasions or as a reward for warriors. It was also sent to religious elites for ritual purposes. The remaining part was assigned to the royal scribes to write codices and other records.

As a tribute item, Amatl belonged to the royal realm as it was not considered an everyday item. This paper was related to power and religion, the method by which the Aztecs imposed and justified their dominance in Central America . As a tribute, it stood for a transaction between the ruling group and the ruled villages. In the second phase, the paper used by the royal authorities and priests for sacred and political purposes was a method of authorizing or authorizing and often registering all other exclusive luxury items.

Amatl paper was manufactured as part of a line of technology aimed at satisfying the human need to express oneself and communicate. Its predecessors were stone, clay and leather for the transmission of knowledge, initially in the form of images, later among the Olmecs and Maya using a form of hieroglyphics . Bark paper had important advantages as it was easier to obtain than animal skins and easier to work with than other fibers. It could be bent, curled, glued and mixed for specific fine work and decoration. Two other advantages promoted the extensive use of bark paper: its low weight and easy portability, which resulted in great savings in time, space and labor compared to other raw materials. In the Aztec region, Amatl paper retained its importance as a writing surface, especially in the production of chronicles and records such as inventories and bookkeeping. Codices became "books" by folding them like an accordion . Of the approx. 500 codices that have survived, around 16 date before the conquest and are made of tree bark paper or bark paper. These include the Dresden Codex from Yucatán , the Fejérváry-Mayer Codex from the Mixteca region and the Borgia Codex from Oaxaca .

From colonial times to the 20th century

When the Spaniards arrived, they noticed the production of codices and paper made from maguey (Ixtli) and palm fibers as well as from tree bark and (Amoxtli) from various rushes Juncus spp. , was manufactured. It was mentioned in particular by Pedro Mártir de Anglería . After the Spanish conquest of Mexico , native paper, especially tree bark paper, lost its value as a tribute item, not only because the Spanish preferred European paper, but also because it was banned because of its connection to the local religion. The justification for the banishment of Amatl was that it was used for magic and witchcraft. This was part of the efforts of the Spanish to convert the locals en masse to Catholicism , which involved the mass burning of codices which contained most of the indigenous history as well as cultural and scientific knowledge.

Only 16 of the 500 codices that survived were written before the conquest. These cocices, written after the conquest, were written on tree bark paper, a few also on European paper, cotton fabric or leather. For the most part, they were the work of missionaries such as B. by Bernardino de Sahagún , who was interested in recording the traditions and knowledge of the local people. The important codices of this type include a. the Codex Sierra , the Codex La Cruz Badiano and the Codex Florentino . The Codex Mendocino was commissioned by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in 1525 to learn about the tribute system and other indigenous traditions in order to adapt them to Spanish rule. However, this was written on European paper.

Although tree bark paper was banned, it did not go away completely. In the early colonial days there was a shortage of European paper, which made it necessary to use the local version occasionally. During the evangelization process, Amatl was approved by the missionaries together with a paste made of corn cane for the production of Christian images, mainly in the 16th and 17th centuries. In addition, the paper was still secretly produced among the locals for ritual purposes. In 1569, the friar Diego de Mendoza observed several locals who were carrying gifts made of paper, copal and woven mats to the lake in the interior of the " Nevado de Toluca " volcano as gifts. Most successful in keeping the papermaking tradition alive have been certain indigenous groups living in La Huasteca , Ixhuatlán and Chicontepec in northern Veracruz and some villages in Hidalgo . The only records of bark papermaking after the early 1800s refer to these areas. Most of these areas are ruled by the Otomí and the roughness and isolation from central Spanish authority allowed small villages to produce small quantities of paper. In fact, the secrecy helped the paper to survive and so defy Spanish culture and reaffirm its own identity.

Late 20th century to the present day

Until the middle of the 20th century. Knowledge of the production of Amatl paper was only found in a few small towns in the rugged mountains of Puebla and Veracruz such as B. San Pablito, an Otomi village, and Chicontepec, a Nahua village, are kept alive. This was particularly strong in San Pablito in Puebla, as many of the surrounding villages believed that this paper had special power when used ritually. The production of paper fell here exclusively into the realm of the shamans, who kept the process secret and mainly made paper to cut out gods and other figures for rituals. However, these shamans came into contact with anthropologists and learned of the interest that people from outside have in their paper and their culture. But although ritual paper-cutting continued to be important to the Otomi people of northern Puebla, the use of Amatl paper gradually declined as industrial paper or tissue paper gradually replaced Amatl paper in rituals. An incentive for the commercialization of Amatl paper was that the shamans became more and more aware of the commercial value of their paper: They began to sell small-scale cutouts of bark paper figures in Mexico City, along with other Otomi handicrafts.

The sale of these figures made bark paper an object of daily use. The paper only became sacred when a shaman cut it as part of a ritual. The manufacture of paper and non-ritual cutting did not conflict with the ritual aspects of paper in general. This allowed the Amatl, previously only used for rituals, to also become something with a market value. It also allowed papermaking to become accessible to the people of San Pablito and not restricted to the shamans.

However, most of the Amatl paper is sold as backing reinforcement for paintings made by Nahua artists from Guerrero state. There are different stories about how the painting on bark paper came about, but the main difference is whether the Nahua or the Otomi came up with the idea. Both the Nahua and Otomi are known to sell handicrafts in the Bazar del Sábado in San Ángel, Mexico City in the 1960s. The Otomi sold their paper and other handicrafts, the Nahua their traditionally painted pottery. The Nahua transferred many of their pottery painting designs onto Amatl paper, which is easier to transport and sell. The Nahua named their paintings after their word for bark paper, namely "Amatl." Today this word is applied to all works of art that use this paper. The new form of painting met with great demand from the beginning, and initially the Nahua bought up almost all of Otomi paper production. Painting on bark and towards the end of the 1960s it became the main economic activity in the eight Nahua villages of Ameyaltepec, Oapan, Ahuahuapan, Ahuelican, Analco, San Juan Tetelcingo, Xalitla and Maxela. Each Nahua village has developed its own style of painting from the tradition of ceramic painting and this allowed the work to be classified.

The triumphant advance of the Amatl came at a time when government policy towards the rural indigenous population and their crafts were changing, with the latter being encouraged, particularly to develop the tourism industry. FONART (Fondo Nacional Para El Fomento De Las Artesanias) became part of the consolidation of efforts to spread Amatl paper. For the most part, this included buying up the entire Otomi production of bark paper to ensure that the Nahua would have enough supplies. Although this intervention only lasted approximately two years, it was the crux of the matter in developing sales of Amatl handicrafts in national and international markets.

While the Nahua are still the main buyers of the Otomi Amatl paper, the Otomi have since branched out into different types of this paper and developed some of their own products for sale. Today, Amatl is one of the most widespread Mexican handicrafts nationally and internationally. It has also drawn artistic and academic attention on both levels. In 2006 an annual event called “Encuentro de Arte in Papel Amatl” was launched in the village and a. with processions, dance of the flies , Huapango music. The main attraction is the exhibition of works by various artists, such as B. Francisco Toledo, José Montiel, Jorge Lozano and many others. The Museo de Arte Popular and the Egyptian Embassy in Mexico City held an exhibition on Amatl and Papyrus in 2008 with over 60 objects comparing the two ancient traditions. One of the most notable artists in this medium is the shaman Alfonso Margarito García Téllez, who exhibited his work in museums such as the San Pedro Museo de Arte in Puebla.

See also

literature

- Rosaura Citlalli López Binnqüist: The endurance of Mexican Amatl paper: Exploring additional dimensions to the sustainable development concept. (PDF; 8.6 MB) , 2003, University of Twente, Enschede.

- Mary Miller , Karl Taube : The gods and symbols of ancient Mexico and the Maya. 1993, Thames and Hudson, London, ISBN 0-500-05068-6 .

- Victor Wolfgang von Hagen : The Aztec and Maya Papermakers. Dover Publications, 1999, ISBN 0-486-40474-9 (reprint).

Web links

- The Construction of the Codex in Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization by Thomas J. Tobin. Maya codex and paper making.

- Codex Espangliensis: A modern art codex printed on amatl paper ( Memento from January 1, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lizeth Gómez De Anda: Papel Amatl, arte curativo (Spanish) . In: La Razón , September 30, 2010. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011 Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e El Papel Amatl Entre los Nahuas de Chicontepec ( Spanish ) Universidad Veracruzana. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Miller and Taube: p. 131.

- ↑ Victor Wolfgang Von Hagen: pp. 37, 67.

- ↑ a b c d Amatl y Papiro… un diálogo histórico Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. In: National Geographic en español . May 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Marna Burns: The Complete Book of Handcrafted Paper. Dover Publications, 1980, ISBN 0-486-43544-X , p. 201.

- ↑ a b Beatriz M. Oliver Vega: El papel de la tierra en el tiempo (German: Native paper in the course of time) ( Spanish ) In: Mexico Desconocido magazine . Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ Tania Damián Jiménez: A punto de extinguirse, el árbol del Amatl en San Pablito Pahuatlán: Libertad Mora (Spanish) . In: La Jornada del Orienta , October 13, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ FONART HOMES. ( Memento of the original from April 5, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ernesto Romero: Pahuatlán: Una historia en papel amatl (Spanish) . In: Periodico Digital , April 13, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2011. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Paula Carrizosa: Exhiben el uso del papel curativo amatl en el pueblo de San Pablito Pahuatlán (Spanish) . In: El Sur de Acapulco , December 6, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2011.