Anne Lister

Anne Lister (born April 3, 1791 , † September 22, 1840 ) was an English landowner and diary writer from Halifax . She kept a life-long diary detailing daily aspects, including her lesbian relationships, financial worries, industrial activities, and her work in developing the Shibden Hall house . Her diaries are 7,720 pages and over 5 million words. About a sixth of these - including those involving the intimate details of their romantic and sexual relationships - have been codedcomposed. This code was derived from a combination of algebra and ancient Greek and was not deciphered until the 1930s. Lister is often referred to as "the first modern lesbian" because of her clear self-awareness and openly lesbian lifestyle. Called Fred by one of her lovers and Gentleman Jack by some of the Halifax residents , she suffered harassment because of her sexuality, but saw what she had in common with the Ladies of Llangollen she was visiting.

Life

Anne Lister was the second child and eldest daughter of Jeremy Lister (1752-1836), who served as a young man in 1775 with the British 10th Regiment of Foot in the battles of Lexington and Concord in the American Revolutionary War. In August 1788 he married Rebecca Battle (1770-1817) from Welton in East Riding, Yorkshire. Their first child, John, was born in 1789 but died that same year. Anne Lister was born in Halifax on April 3, 1791. In 1793 the family moved to an estate called Skelfler House in Market Weighton . Skelfler was the place where young Anne spent her first years. A second son, Samuel, who was closely related to Anne, was born in 1793. The Listers had four sons and two daughters, but only Anne and her younger sister Marian survived the age of 20.

Between 1801 and 1805 Lister was homeschooled by Reverend George Skelding, Vicar of Market Weighton . At the age of seven she was sent to a school run by a Mrs. Hagues and a Mrs. Chettle in Agnesgate, Ripon. During her visits to Shibden Hall with her aunt Anne and uncle James, she was tutored by the Misses Mellin. In 1804 Anne Lister was sent to the Manor House School in York (in the buildings of King's Manor ), where Anne met her first love, Eliza Raine (1793-1860). Eliza and her sister Jane were the very wealthy daughters of an East India Company surgeon in Madras who came to Yorkshire after his death. Anne and Eliza met at boarding school when they were 13 and shared a room, but Anne was asked to leave school after two years. She went back to school after Eliza left. Eliza expected to live with Anne as adults, but Anne began affairs with Isabella Norcliffe and Mariana Belcombe, day pupils at the school. In desperation and frustration, Eliza became a patient at the Clifton Asylum run by Mariana's father, Dr. Belcombe, was headed. Eliza Raine was later moved to Terrace House in Osbaldwick and died there on January 31, 1860. She is buried in Osbaldwick churchyard. While she was home raised, Lister developed an interest in classical literature. In a received letter to her aunt dated February 3, 1803, the young Lister explains: "My library is my greatest pleasure ... I liked Greek history very much."

She inherited Shibden Hall after her aunt's death in 1836, but had owned it since 1826, and received a decent income from it (partly from tenants). This allowed her some degree of freedom to live the way she wanted. In addition to the income from the agricultural lease, Lister's financial portfolio also included real estate in the city, shares in the canal and railroad industries, mining and quarries. With the income from this diverse portfolio, Lister financed her two passions, Shibden Hall and European trips.

Lister is described as a "masculine appearance"; one of her lovers, Mariana Lawton (née Belcombe), was initially ashamed to be seen with her in public because there was commentary on her appearance. She dressed all in black and participated in many activities that were not considered to be the norm for women at the time, such as: B. opening and owning a mine . In some circles she was referred to as "Gentleman Jack". Lawton and Lister were lovers for several years, including a period when Lawton was married and her husband had given up.

Although Lister had met her on several occasions during the 1820s, Ann Walker , who had become a wealthy heiress in 1832, played a much more prominent role in Lister's life. Finally, on Easter Sunday (March 30th) 1834, the women went to Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, York, to communion together and were then considered married, albeit without legal recognition. The church is described as "an icon of what is interpreted as the site of the first lesbian marriage in Britain" and the building now has a blue plaque. The couple lived together at Shibden Hall until Lister's death in 1840. Walker's fortune was used to enhance Shibden Hall and the property's waterfall and lake. Lister made a major renovation of Shibden Hall from her own design. In 1838 she added a Gothic tower to the main house, which was to serve as her private library. She also had a tunnel dug under the building through which the staff could move without disturbing them. Throughout her life, Lister had a strong Anglican faith and a supporter of the Tory who "defended the privileges of the landed nobility."

to travel

Lister enjoyed traveling very much, although her biographer Angela Steidele suspects that her travels in later life were also a way of escaping the self-realization that she had failed in everything she tackled. She made her first trip to continental Europe in 1819 when she was 28 years old. She traveled to France for two months with her 54-year-old aunt, who was also called Anne Lister.

She returned to Paris in 1824 and stayed until the following year. In 1826 she was back with her aunt Anne in Paris, where she resumed an affair from her previous visit to the city with a widow named Maria Barlow. In 1827 she set out from Paris with Maria Barlow as well as with her aunt Anne on a trip to northern Italy and Switzerland. She did not return to Shibden Hall until 1828.

In 1829 she traveled to the continent again. From Paris, she visited Belgium and Germany before heading south to the Pyrenees. Here she went hiking and also crossed the border into Spain. There she demonstrated her strong thirst for adventure as well as her considerable physical fitness by climbing Monte Perdido (3,355 m), the third highest peak in the Pyrenees .

When she returned to Shibden Hall in 1831, she found life with her father Jeremy and sister Marian so uncomfortable that she left almost immediately and took a short trip to the Netherlands with Mariana Lawton. Overall, she only spent a few weeks at Shibden Hall between 1826 and 1832, with travel around the UK and Europe allowing her to avoid her family at home.

In 1834 she visited France and Switzerland again, this time for her honeymoon with Ann Walker. When she returned with Ann in 1838, she set out again south into the Pyrenees and completed the first "official" ascent of Vignemale (3,298 m), the highest peak in the French Pyrenees. This required a 10 hour hike to get to the top and another 7 to descend.

Their last and greatest journey began in 1839. They left Shibden Hall in June with Ann Walker and two servants and traveled in their own carriage through France, Denmark, Sweden and Russia, where they were in St. Petersburg in September and in Moscow in October arrived. With a reluctant Ann Walker in tow, she left Moscow in February 1840 in a new Russian carriage and very warm clothes. They traveled south, along the frozen Volga, to the Caucasus . Few Western Europeans had visited this area, let alone Western European women, partly because of the unrest among the local population against the Tsarist regime. At times they needed a military escort. The two women were a source of great curiosity to the people who visited them. Anne noted in her diary: "People come and stare at us as if we were strange animals that they have never seen".

death

Lister died of a fever on September 22, 1840 at the age of 49 in Koutais (now Kutaisi , Georgia ) while traveling with Ann Walker. Walker had Lister's body embalmed and brought back to Great Britain, where it was buried on April 29, 1841 in the parish church in Halifax, West Yorkshire. Her tombstone was rediscovered in 2010 after it was covered under a floor slab in 1879.

In her will, Lister's estate was bequeathed to her paternal cousins, but Walker received a portion for life. After she was declared insane, Walker spent several years in the care of Dr. Belcombe and was unable to make a valid will due to her mental condition. She died in 1854 at her childhood home, Cliff Hill in Lightcliffe, West Yorkshire.

More than 40 years after her death, the Leeds Times stated in an 1882 report of a dispute over ownership of Shibden Hall: "Miss Lister's masculine singularities of characters are still remembered."

Diaries

Lister wrote a diary throughout her life. It began in 1806 as scraps of paper recorded in secret code packets by and to Eliza Raine, and eventually grew into the 26 quarto volumes that ended with her death in 1840. Aside from the fact that her handwriting is difficult to decipher, about one sixth of the diary is encoded in a simple code she and Eliza came up with, which combines the Greek alphabet, the zodiac, punctuation and mathematical symbols. and it describes in great detail her lesbian identity and affairs, as well as the methods she used to seduce., The diaries also contain her thoughts on the weather, social events, national events, and her business interests. Most of her diary deals with her daily life, not just her sexuality, and provides detailed information about social, political and economic events of the time.

Again and again the diaries and correspondence were tracked down and then fell into oblivion again. The sheer amount of material made it difficult to fully develop. In addition to the diaries, there are over 1000 letters. In addition, Lister worked a lot with abbreviations and letter codes, which made it impossible to quickly skim through the text. Another reason lies in the wide range of topics in the diaries, that "they go beyond the categories commonly used by historians". The topics range from industrialization in the 19th century and the power of the landed aristocracy in this time, to the detailed description of their relationships with women and travel in Europe. It wasn't until 1984 that Lister's diaries caught national attention when an article in the Guardian entitled "The two million word enigma" alerted readers to Anne Lister's upcoming 1991 bicentenary made.

The code used in their diaries was deciphered by the last resident of Shibden Hall, John Lister (1847–1933) and a friend of his, Arthur Burrell. When the contents of the secret passages were revealed, Burrell advised John Lister to burn all diaries. Lister did not take this advice and continued to hide Anne Lister's diaries behind a blackboard in Shibden Hall.

In 2011 Lister's diaries were added to the UNESCO Memory of the World program register. The register quotation states that although the diaries are a valuable historical testimony, "the comprehensive and painfully honest portrayal of lesbian life and the reflections on their nature have made these diaries unique. They have shaped and continue to shape the direction of British gender studies and women's history . "

Lister's diaries have been described as part of a "trilogy of early 19th century diaries" covering the same period from different perspectives, along with those of Caroline Walker from 1812 to 1830 and Elizabeth Wadsworth from 1817 to 1829.

Anne Lister's diaries were also added to the United Kingdom's World Document Heritage List in 2011.

research

Helena Whitbread published some of the diaries in two volumes (1988 and 1992). Because of their imagery, they were initially thought by some to be a hoax, but their authenticity has now been proven by documents. A biography of the scientist Jill Liddington was published in 1994. In 2014, a conference took place in Shibden Hall that dealt with Lister's life as well as gender and sexuality in the 19th century.

A German-language biography of Angela Steidele was published in 2017 , which was published in English in 2018.

The work of Dorothy Thompson and Patricia Hughes in the late 1980s in the Department of Modern History at the University of Birmingham resulted in the translation of much of the code as well as the discovery of the first youthful Lister diaries and the deciphering of the other two Lister codes. Hughes self-published Anne Lister's Secret Diary for 1817 (2019) and The Early Life of Miss Anne Lister and the Curious Tale of Miss Eliza Raine (2015), both of which make extensive use of other materials in the Lister archives, including letters, Diaries and additional documents.

Popular culture

Julia Ford as Anne Lister and Sophie Thursfield as Marianna Belcombe appear in the first episode of BBC Two's 1994 series A Skirt Through History, "A Marriage ."

On May 31, 2010, BBC Two aired a production based on Lister's life, The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister , starring Maxine Peake as Lister. Revealing Anne Lister , a documentary starring Sue Perkins , aired on BBC Two that night.

Chamber folk duo O'Hooley & Tidow recorded a song about Anne Lister, "Gentleman Jack", on their 2012 album The Fragile.

The historic TV drama series Gentleman Jack, produced by BBC and HBO in 2019 and starring Suranne Jones as Lister, portrays her life as the "first modern lesbian". The series is said to be "inspired by" two books about Lister by Jill Liddington, Female Fortune and Nature's Domain . Liddington also acted as a consultant for the series. O'Hooley & Tidow's "Gentleman Jack" serves as the series' primary theme music. Penguin Books published a companion volume by Anne Choma, the series' lead advisor, which contains newly transcribed and decoded entries from Lister's diaries.

honors and awards

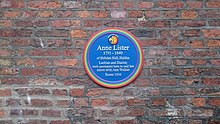

In 2018, a blue plaque in honor of Lister was unveiled at Holy Trinity Church in York; it was the first LGBT history plaque in York. The board had a rainbow border. The wording on the board was criticized for not mentioning Lister's sexuality. In 2019 it was replaced by a similar plaque with the wording "Anne Lister 1791-1840 of Shibden Hall, Halifax / Lesbian and Diarist; took sacrament here to seal her union with Ann Walker / Easter 1834".

See also

literature

- Choma, Anne, Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister. (Penguin Books & BBC Books, 2019)

- Green, Muriel, Miss Lister of Shibden Hall: Selected Letters (1800-1840) . (The Book Guild Ltd, 1992)

- Hughes, Patricia, Anne Lister's Secret Diary for 1817 . (Hues Books Ltd 2006)

- Hughes, Patricia, The Secret Life of Miss Anne Lister and the Curious Tale of Miss Eliza Raine . (Hues Books Ltd 2010)

- Liddington, Jill , Presenting the Past: Anne Lister of Halifax, 1791-1840 . (Pennine Pens, 1994)

- Liddington, Jill, Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: The Anne Lister Diaries and Other Writings, 1833–36 . (Rivers Oram Press, 1998)

- Steidele, Angela, Anne Lister. An erotic biography. (Matthes & Seitz Berlin, 2017)

- Steidele, Angela, time travel. four women, two centuries, one way (Matthes & Seitz Berlin, 2018)

- Vicinus, Martha, Intimate Friends: Women Who Loved Women, 1778-1928 . (University of Chicago Press, 2004)

- Whitbread, Helena , I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister 1791-1840 . ( Virago , 1988)

- Whitbread, Helena, No Priest But Love: Excerpts from the Diaries of Anne Lister . (NYU Press, 1993)

Web links

- Anne Lister's encoded diary - shows scanned images of Anne Lister's encoded diary pages

- Anne Lister page at From History to Her Story: Yorkshire Women's lives on-line - presents excerpts from her translated diaries, as well as pictures from the original

- The West Yorkshire Archive Service - keeps Anne Lister's diaries

- Doris Hermanns: Anne Lister. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

Individual evidence

- ^ The life and loves of Anne Lister . May 25, 2010 ( online [accessed January 16, 2021]).

- ^ Anne Lister - An Introduction - Catablogue <! - not a typo! ->. September 18, 2019, accessed November 10, 2019 .

- ^ Anne Lister - Diary Transcription Project. In: Catablogue. July 6, 2019, accessed January 17, 2021 .

- ↑ The Ladies of Llangollen. Accessed January 17, 2021 .

- ^ The London Gazette . A12162 ( online [PDF]).

- ^ A b Sir William Dugdale: Dugdale's Visitation of Yorkshire, with Additions . W. Pollard & Company, 1894, p. 118 (English, online [accessed December 6, 2018]).

- ↑ Muriel Green: Miss Lister of Shibden Hall: Selected Letters (1800-1840) . The Book Guild, Sussex, England 1992, ISBN 0-86332-672-2 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Patricia Hughes: The Early Life of Miss Anne Lister and the Curious Tale of Miss Eliza Raine . 2010.

- ↑ Muriel Green: Miss Lister of Shibden Hall: Selected Letters (1800-1840) . 1992, p. 7, 19 .

- ↑ | The parish of St Thomas Osbaldwick with St James Murton | About the Parish | St Thomas's |. Retrieved January 17, 2021 .

- ↑ Helena Whitbread: No Priest but Love: Excerpts from the Diaries of Anne Lister, 1824-1826 . New York University Press, 1992, pp. 2 .

- ↑ a b c d e The life and loves of Shibden Hall's Anne Lister . In: BBC . May 25, 2010 ( online [accessed January 17, 2021]).

- ^ A b c d Jill Liddington: Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax (1791-1840): Her Diaries and the Historians . In: History Workshop Journal . 35, No. 35, April, pp. 45-77. doi : 10.1093 / hwj / 35.1.45 .

- ^ A b c d Rictor Norton: Anne Lister: The First Modern Lesbian . In: Lesbian History . Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ Terry Castle: Review: The Pursuit of Love . In: The Women's Review of Books . 6, No. 4, April, pp. 6-7. doi : 10.2307 / 4020468 .

- ↑ Elizabeth Mavor: Gentleman Jack of Halifax . In: London Review of Books . 10, No. 3, April. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Anne Choma: Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister . Penguin Books, 2019, pp. 66 .

- ↑ Harriet Sherwood: Recognition at last for Gentleman Jack, Britain's 'first modern lesbian'. In: The Guardian . July 28, 2018, accessed January 17, 2021 .

- ↑ a b c Caroline Crampton: The lesbian Dead Sea Scrolls: Anne Lister's diaries. In: New Statesman . December 5, 2013, accessed January 17, 2021 .

- ^ Anna Clark: Anne Lister's Construction of Lesbian Identity . In: Journal of the History of Sexuality . 7, No. 1, p. 35, April.

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 302 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 376 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 99 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 172 .

- ↑ Nanou Saint-Lèbe: Les Femmes à la découverte des Pyrénées . Private, Toulouse 2002 (French).

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 245 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 245 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 242 .

- ↑ Vivien Ingham: Anne Lister's Ascent of Vignemale . In: Alpine Journal . 73, items 316-317, April. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 361-364 .

- ↑ a b Angela Steidele: Time travel. four women, two centuries, one way . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-95757-635-4 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 399 .

- ^ Angela Steidele: Anne Lister. An erotic biography . Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95757-445-9 , pp. 432 .

- ↑ a b c The Shibden Hall Estate. In: Leeds Times. July 22, 1882, Retrieved February 5, 2015 .

- ↑ The Story of Anne Lister ( EN )

- ^ Jill Liddington: Anne Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax (1791-1840): Her Diaries and the Historians . In: History Workshop Journal . 35, No. 1, April, pp. 45-77. doi : 10.1093 / hwj / 35.1.45 .

- ↑ Leila J. Rupp: A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America . The University of Chicago Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-226-73156-8 , pp. 10 .

- ↑ a b UK Memory of the World Register . In: UK National Commission for UNESCO . UNESCO . 2011. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- ^ WB Trigg: Miss Wadsworth's Diary . Halifax Antiquarian Society, West Yorkshire Archive Service 1943, p. 123 .

- ↑ Memory of the World - UNESCO in the UK , accessed January 17, 2021.

- ^ Anne Lister's diaries win United Nations recognition . In: BBC News . June 1, 2011 ( online [accessed January 17, 2021]).

- ↑ Anne Lister. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- ^ Anne Lister Conference The Inaugural Anne Lister Conference; women, gender and sexuality in the 19th Century . Archived from the original on May 25, 2014.

- ↑ Patricia Hughes: Anne Lister's Secret Diary for 1817 . Hues Books, 2019, ISBN 978-1-909275-30-0 ( online ).

- ↑ Eliza Raine, Patricia Hughes: The Early Life of Miss Anne Lister and the Curious Tale of Miss Eliza Raine . Hues Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1-909275-06-5 ( google.com ).

- ↑ Collections Search | BFI | British Film Institute. Retrieved January 18, 2021 .

- ^ A Skirt through History . In: The Radio Times . No. 3668 , April 28, 1994, ISSN 0033-8060 , p. 94 ( online [accessed January 18, 2021]).

- ^ Revealing Anne Lister . In: BBC Two Programs . BBC. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Music and Performance: Interview with O'Hooley and Tidow . When Sally Met Sally. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved on September 15, 2012.

- ↑ Jill Liddington: Who was Anne Lister? . Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Anne Choma: Gentleman Jack: The Real Anne Lister . Penguin Randomhouse, 2019, ISBN 978-0-14-313456-5 ( online [accessed March 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Anne Lister: plaque wording to change after 'lesbian' row . September 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ↑ Video: York's rainbow plaque to Anne Lister is back - with the word 'Lesbian' front and center . In: YorkMix . January 29, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Rainbow Plaque Unveiling | York Civic Trust ( en-GB )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lister, Anne |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English landowner and diary writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 3, 1791 |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 22, 1840 |