Saccharin

| Structural formula | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Surname | Saccharin | |||||||||||||||||||||

| other names | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 7 H 5 NO 3 S | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Brief description |

colorless and odorless, crystalline solid |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar mass | 183.19 g mol −1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical state |

firmly |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| density |

0.83 g cm −3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point |

228.8-229.7 ° C |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| solubility |

soluble in water: 3.3 g · l −1 (20 ° C), more soluble in boiling water and ethanol |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| safety instructions | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Saccharin ( old Gr . Σάκχαρον sakcharon "sugar") is the oldest synthetic sweetener . It was discovered in 1878 by the chemists Constantin Fahlberg and Ira Remsen at Johns Hopkins University (USA). They informed about this on February 27, 1879.

As a food additive , saccharin has the designation E 954, the permitted daily dose is 5 mg / kg body weight.

From a chemical point of view, saccharine is an o -benzoic acid sulfimide, it contains a lactam unit and a cyclic sulfonamide unit . It is derived from the phthalimide , in which a carbonyl group has been replaced by a sulfone group , thereby significantly increasing the NH acidity .

history

After Constantin Fahlberg's reaction got out of control and boiled over, he noticed a sweet taste on his hands. The substance that was responsible for this has come to be known as saccharin. A patent application was made for saccharin.

On the basis of this patent, Fahlberg and the businessman Adolph List founded the first saccharin factory in Magdeburg, the Fahlberg-List factory . In 1894 the annual production was 33 t and three years later it doubled to 66 t. In 1910, six saccharin manufacturers produced 175 t per year.

In terms of sweetening power, saccharin was around two thirds cheaper than conventional beet sugar around 1890 , so that the beet sugar industry was expected to be displaced. Due to the difficulties with handling, saccharin could not establish itself in the private kitchen at that time. Housewives complained that the amount for a cup of tea was practically impossible to dose and the powder was not suitable for dusting cakes.

As a result of interventions by the sugar industry, sweeteners were banned in Germany in 1902. Production was only allowed for the needs of diabetics. Similar bans existed in almost all European countries with the exception of Switzerland , where saccharin continued to be produced and illegally imported into Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary and Russia on a large scale ( saccharin smuggling ).

After the Second World War , sweeteners were allowed again.

In 1912, after tough negotiations, the US Department of Agriculture published Food Inspection Decision 142 based on the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1907. The decision bans saccharin as an ingredient in normal foods. During the First World War , saccharine was again allowed to be used as an ingredient. A lawsuit by the head of the USDA chemistry laboratory against Monsanto Chemical Works was unsuccessful in 1916. In 1920 the US government filed a lawsuit against Monsanto, which allegedly violated the Pure Food and Drug Act through extensive sales of the "unhealthy" saccharin . Since the government was unable to adequately prove its allegations, the jury did not reach a verdict. In 1924, too, a government action failed before a jury. The lawsuits were finally dismissed in 1925.

properties

Saccharin is 300 to 700 times sweeter than sugar . It can cause a bitter or metallic aftertaste, especially in higher concentrations. Unlike the newer artificial sweetener aspartame , saccharin remains stable when heated, even when acids are present. In addition, it does not react chemically with other substances and is easy to store.

Mixtures with other sweeteners such as cyclamate , thaumatin or acesulfame have the purpose of eliminating the disadvantages of the various sweeteners. A mixture of cyclamate and saccharin in a ratio of 10: 1 is common in countries where both sweeteners are legal - here both substances hide each other's (unpleasant) aftertaste.

Saccharin does not cause tooth decay . Saccharin is colorless, is quickly absorbed by the human body and excreted unchanged in the urine (after 24 hours already 90%). Saccharin has almost no physiological energy content and is therefore, like all sweeteners, also suitable for diabetics .

Manufacturing

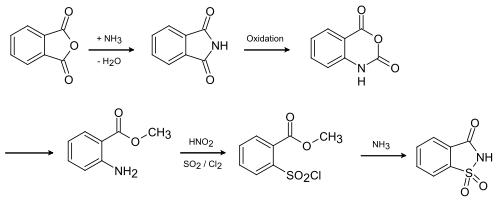

Saccharin is chemically produced from toluene using the Remsen-Fahlberg process .

In the last step, it is first oxidized with potassium permanganate before the imide is formed with elimination of water.

Another possibility is the production from phthalic anhydride according to the newer Maumee process , which, however, is less used.

use

Saccharin is used in diet foods, in light products and as a flavor enhancer. It may only be used in certain foods with a specified maximum value. For example, the maximum value in jams is 200 mg / kg, in canned fruit and vegetables 160 mg / kg and in energy-reduced drinks 80 mg / l.

In the production of feed for piglets, saccharine is used as a sweetener, but not to stimulate the appetite.

Dental care products ( toothpaste , dental care chewing gum) contain saccharine as a sweetening, non-caries-promoting substance.

In electroplating , saccharine is used for surface coating; it helps here for a uniform and tension-free nickel coating.

effect

In addition to the well-known sweetening effect of saccharin, effects on feelings of hunger and insulin release are also discussed; see the article sweetener . Saccharin acts as a carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitor in the test tube, type VII CA is most strongly inhibited. CA is an enzyme that is involved in numerous physiological processes in the body, CA-VII is localized in the brain. Saccharin also has an antibiotic effect on the intestinal flora, which is attributed to the sulfonamide unit . Studies have shown that it can trigger obesity and diabetes, suspected to be the altered intestinal flora . Saccharin is suspected of promoting the development of Alzheimer's disease .

Saccharin and cancer

Since its introduction, saccharin has been examined several times for its health safety.

In the 1960s, it was found in various studies that saccharin can have a carcinogenic (carcinogenic) effect in animals . In 1977 a study was published in which rats fed high doses of saccharin showed an increase in bladder cancer in the males . In the same year, saccharin was banned in Canada . The US FDA was also considering a ban, however saccharin was the only available artificial sweetener in the US at the time and this consideration met with strong public opposition, especially among diabetics. It was not banned, but food containing saccharine had to be given a warning from February 1978. In 2000 this regulation was repealed. Since then, the possible carcinogenic effect has been the subject of numerous studies. While some studies found a link between saccharin consumption and increased cancer rates (especially bladder cancer), other studies could not confirm this. A meta-study from 2004 rated a possible cancer risk as insignificant.

No study has been able to confidently confirm health risks in humans (when consuming normal doses). In addition, it was shown that the biological mechanism that causes cancer in rats cannot be directly transferred to humans due to the different urine composition. The influential studies of 1977 were also criticized for the very high doses of saccharin fed to the rats, which often exceeded the normal human consumption by a hundred times.

Others

An extremely potent nasopharyngeal irritant is derived from saccharin. It is the tri- n -propyllei- O -sulfobenzimid in which the imino hydrogen has been replaced by a tri- n -propyllei radical. The substance was described in 1947 by Saunders in the literature. In a dilution of 1: 25 million, it still causes irritation of the nasopharynx and leaves a sweet taste.

literature

- Klaus Roth , Erich Lück: The Saccharin Saga, Chemistry in Our Time , 2011, 45 (6), pp. 406-423, doi: 10.1002 / ciuz.201100574 .

- Hubert Olbrich : Saccharin, its production and handling: Contribution to the history of bans and the defense against smuggling, to the customs reform and the establishment of customs museums Technical University Berlin, German Museum of Technology Berlin, area: Sugar Museum, specialist department: Sugar and sugar industry, 2nd expanded edition , Berlin: Universitäts-Verlag der TU Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7983-2493-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ entry to SACCHARIN in CosIng database of the European Commission, accessed on February 26 2020th

- ↑ a b c d Data sheet saccharin (PDF) from Merck , accessed on December 25, 2019.

- ↑ a b entry on saccharin. In: Römpp Online . Georg Thieme Verlag, accessed on June 1, 2014.

- ^ The Merck Index. An Encyclopaedia of Chemicals, Drugs and Biologicals. 14th edition, 2006, ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1 .

- ↑ Bettina Neuse-Schwarz: Saccharin as a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor , Pharmazeutische Zeitung , 41/2007.

- ^ C. Fahlberg and I. Remsen: Ueber die Oxydation des Orthotoluolsulfamids , reports of the German Chemical Society , 12 (1879), pp. 469-473, doi: 10.1002 / cber.187901201135 .

- ↑ Clara von Studnitz, Fürs Haus, practical weekly paper for all housewives, August 31, 1889.

- ^ Christian Litz: Tour de sweetness. (PDF; 523 kB) 2008, accessed June 1, 2013 .

- ↑ Klaus Roth, Erich Lück: The Saccharin Saga. Translated by W. E. Russey. In: ChemistryViews . ( doi: 10.1002 / chemv.201500087 ).

- ↑ a b P. M. Priebe, GB Kauffman: Making governmental policy under conditions of scientific uncertainty: a century of controversy about saccharin in Congress and the laboratory. In: Minerva. Volume 18, Number 4, 1980, pp. 556-574, PMID 11611011 .

- ↑ Year book of the American Pharmaceutical Association Volume 9, American Pharmaceutical Association 1922, p. 588.

- ^ Williams Haynes (1948), American chemical industry, 4: 304.

- ↑ Christoph Drösser: That's right / Right: sweetener for piglets , Die Zeit, April 3, 2008 (about the myth of the appetizing effect of artificial sweeteners).

- ↑ Answer of the European Institute for Food and Nutritional Sciences Munich to the Die Zeit article ( Memento from July 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Carsten Thöne, Klaus Schmid, Martin Metzner: Influence of saccharine on the internal stresses in nickel layers . In: Galvanotechnik 98 (2007), No. 11, pp. 2650-2652.

- ↑ http://flexikon.doccheck.com/de/Carboanhydrase

- ↑ Udo Pollmer: Meal, Diabetes: Beware of Sweeteners , Deutschlandfunk Kultur, broadcast on February 9, 2018.

- ^ MR Weihrauch, V. Diehl: Artificial sweeteners - do they bear a carcinogenic risk? In: Annals of Oncology . Volume 15, Number 10, October 2004, pp. 1460-1465, doi : 10.1093 / annonc / mdh256 , PMID 15367404 (review).

- ↑ H. McCombie, BC Saunders: Toxic organo-lead compounds. In: Nature . Volume 159, Number 4041, April 1947, pp. 491-494, PMID 20295226 .