Mining in the Upper Palatinate

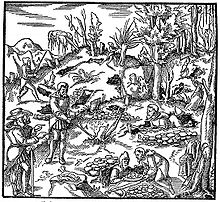

The mining industry in the Upper Palatinate had its economic heyday between the 14th and the 17th century. The region was considered one of the most lucrative principalities of Europe . In addition to Styria , Carinthia and Siegerland , the Upper Palatinate was one of the largest centers of iron ore mining and iron production in the German-speaking area at this time.

The advantage for this was that in the sparsely populated Upper Palatinate, the raw materials water and wood required for this were originally abundant. In the neighboring Fichtelgebirge there was also intensive mining for tin and silver .

In the middle of the 19th century, the region experienced a renewed boom, until mining finally came to a standstill in 1964.

Beginning and extent of ore mining in the Upper Palatinate

There is no reliable knowledge about the beginnings of the mining industry in the Upper Palatinate. However, new archaeological and settlement history research indicates that in the Amberg-Sulzbach area extensive iron ore was mined and further processed as early as the Carolingian period . For Amberg, for example, smelting in the Ottonian period, and for Sulzbach, in addition to iron smelting and processing, also highly specialized non-ferrous metal craft can be traced back to the late Carolingian period. It is conceivable that the high-quality chalk ores in this area were already known and mined in the Iron Age, but at the moment this cannot be directly proven by archaeologically researched smelting sites.

Iron production in the Upper Palatinate can be regarded as significantly far beyond the region from the middle of the 13th century at the latest. A few authors of the 20th century therefore tried to establish the term Ruhr area of the Middle Ages . In 1219 the Bergregal was transferred to Duke Ludwig I by the later Emperor Friedrich II . However, the sovereign initially left all mining powers to the mining centers of Amberg and Sulzbach. This was formally established in 1348 for Sulzbach and shortly thereafter in 1350 for Amberg. The sovereign reserved the mountain tithe, but in a few years it was also left to the cities, so that, for example, the city fortifications of Amberg could be completely financed with it. Beginning in 1455 and reinforced by the new mining regulations in 1457 and 1465, the urban mining privileges of Amberg and Sulzbach were increasingly curtailed, so that the sovereign was able to gain greater access to the proceeds of mining.

Two-wheeled carts were used to transport ore and coal. In 1475, 93,200 loads of ore had to be transported in the Upper Palatinate, with an average distance of 40 km. In addition, there were 20,000 loads for transporting iron and 122,000 loads for transporting charcoal. At the Erzberg zu Amberg , 121,000 t of iron ore were mined in 1595/96. Over 1000 miners worked here, as well as 173 horses. The ores extracted this year had a value of 118,000 Rhenish gold guilders . Most of the transports were made by the farmers in the winter months, which was a good extra income. With the flourishing of the industry, farmers increasingly abandoned their fields and drove for the hammers in summer too. Because of this, the sovereign government limited the number of mandates in the 16th century in order to curb driving outside the winter months, but this did not help much.

The industrial development gave the region an immense upswing in the Middle Ages. In mining , depths of 100 to 200 meters have already been reached. The centers of ore mining were in Amberg , Sulzbach , Auerbach and the surrounding area. Many steelworks developed around these centers and countless hammers and hammer mills throughout the Upper Palatinate . Place names such as Weiherhammer still bear witness to this time. In these hammers the products were made that established the reputation of the Upper Palatinate as the Ruhr area of the Middle Ages.

Consequences of the economic boom

However, the immense upswing caused by the numerous smelting works and hammer mills also brought disadvantages with it, after all they resulted in largely disordered forest felling with corresponding consequences. It is reported from Vilseck in 1348 that a number of iron hammers had to be shut down because the local forest had been used up by the charcoal burners to produce the charcoal they needed in large quantities , which was all the worse since the wood and other products of the forest ( honey , wax ) were used for an important raw material for the rural population for many other purposes. Ecologically problematic was that the forestry that was now emerging replaced the natural mixed forest of oaks and beeches with rapidly growing coniferous forests. This resulted in a large number of forest orders that tried to regulate logging. Auerbach even had its own forest dish . Wildlife and forest crime were punished with drastic penalties. The farmers' free logging for firewood and construction wood was restricted, although they had to pay taxes for the electoral and monastic forests. Over and over again there were conflicts. The demand for free logging was one of the most important demands of the farmers in the Peasants' War of 1525 .

The Hohenstaufen emperors, later the Nuremberg emperors, promoted the Upper Palatinate coal and steel industry, which remained dominant for over three centuries. At the turn of the 16th century, a third of all German ore mining was still provided in the Upper Palatinate.

end of an era

Due to the dramatic changes in the 16th century through the discovery of new continents, new technologies and finance, the Upper Palatinate lost its economic importance. The Hussite storms , the Thirty Years' War and the following political developments also contributed to this.

The Bavarian Iron Road , a holiday route from Pegnitz to Regensburg, is a reminder of the history of the East Bavarian mining industry .

Literature / sources

- Konrad Ackermann : The Upper Palatinate. Main features of their historical development. Bayer. Mortgage u. Wechsel-Bank, Munich 1987.

- Mathias Hensch : Mining archeology in the Upper Palatinate - forgotten by research? In: Reports on the Bavarian monument preservation. 43/44, 2002/3, Munich 2005, pp. 273-288.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Bingener, Christoph Bartels, Michael Fessner: The great time of silver . In: Christoph Bartels, Rainer Slotta (Ed.): The old European mining. From the beginning to the middle of the 18th century. (= History of German Mining . Volume 1 ). Aschendorff, Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-402-12901-2 , pp. 433 .

- ↑ a b Website of the Berg- und Industriemuseum Ostbayern

- ↑ Christoph Bartels, Lothar Klappauf : The Middle Ages . In: Christoph Bartels, Rainer Slotta (Ed.): The old European mining. From the beginning to the middle of the 18th century. (= History of German Mining . Volume 1 ). Aschendorff, Münster 2012, ISBN 978-3-402-12901-2 , pp. 188 .

- ^ Franz Michael Ress: The iron trade of the Upper Palatinate in old times. Oldenbourg, Munich 1951, p. 6.

- ^ Franz Michael Ress: Buildings, monuments and foundations of German ironworkers . Written on behalf of the Association of German Ironworkers . Verlag Stahleisen, Düsseldorf 1960, DNB 453998070 , p. 310 .

- ^ Homepage of the Bavarian Eisenstrasse