Carlton Club Meeting (1922)

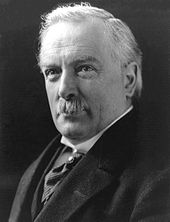

The Carlton Club meeting of 1922 was a meeting of the members of parliament of the British Conservative Party (German: Conservative Party) on October 19, 1922. It took place in the eponymous Carlton Club . The occasion was an open discussion about the question of whether the party should continue or end the coalition government with the part of the Liberal Party led by David Lloyd George beyond the next general election. While the party leadership around Austen Chamberlain advocated a continuation of the coalition, a backbencher group around Andrew Bonar Law and Stanley Baldwin campaigned for the upcoming general election as an independent force. The backbenchers were able to prevail and thus forced an end to the coalition. Lloyd George then resigned as prime minister, while the Conservatives formed a government under their new chairman Bonar Law.

The meeting had far-reaching implications. Lloyd George, who had dominated the British political scene in recent years, never held political office again. A possible split in the conservatives, however, was prevented, as was the merger of moderate conservatives and liberals into a new center party operated by Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead and Winston Churchill . In the British political landscape, in which two parties are traditionally opposed to each other due to majority voting rights, an inconsistent three-party system developed over the next few years, consisting of Conservatives, Liberals and Labor (German: Labor Party), with the Liberals in this phase as opponents of the Conservatives were gradually replaced by the rising Labor Party.

The Carlton Club meeting is also featured in today's political coverage in the British media and is regularly quoted to underscore the power of the conservative backbenchers.

background

Since its clear defeat in the 1906 general election, the Conservative Party had been in opposition for years. The social reform laws of the ruling liberals , which were largely promoted by Prime Minister HH Asquith and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George , met fierce resistance from the Conservatives. Above all the so-called “People's Budget” (a legislative package with extensive taxes on landowners to finance social measures), the subsequent Parliament Act 1911 , which radically curtailed the veto right of the conservatively dominated House of Lords , and the ongoing Home Rule -Questions about the Irish self-government caused bitter disputes. The Conservatives represented the interests of the landowners and traditionally defined themselves as resolute opponents of Irish self-government - that is how they officially called themselves, from 1912 onwards, the "Conservative and Unionist Party". The bitter conflicts over the House of Lords' right of veto ultimately led to internal party upheavals within the conservatives; a group around Lord Halsbury (unsuccessfully) demanded total opposition at all costs. This right wing was called "Ditchers" or "Die-hards" (derived from the English idiom die in the last ditch , German about fight to the bitter end ) because of its uncompromising attitude . The Halsbury group could not prevent the passage of the Parliament Act, but successfully agitated against what they saw as the all too hesitant party leader Arthur Balfour , who resigned in November 1911. He was succeeded by Andrew Bonar Law .

The beginning of World War I in August 1914 initially led to a standstill agreement in party politics to demonstrate national unity. The Conservatives themselves referred to this as "patriotic opposition". However, in the face of increasing military defeats and repeated setbacks, this agreement had increasingly reached its limits. Above all, Winston Churchill's relentlessly pursued “Dardanelles Strategy” with the aim of pushing the Ottoman Empire out of the war and thus creating a safe sea route to ally Russia was controversial; the resulting fatal and costly Battle of Gallipoli had led to violent clashes and ultimately to the resignation of the First Sea Lord John Arbuthnot Fisher . This and the so-called ammunition crisis of 1915 (a shortage of artillery shells among British troops on the Western Front) also caused severe criticism from the British press. Under these circumstances, a further sole government of the liberals and a standing still of the conservative opposition had become increasingly impossible. Therefore, in 1915, a coalition was formed between the Liberals, led by Prime Minister Asquith, and the Conservatives around their party leader Andrew Bonar Law. In addition, this government was supported by parts of the Labor Party - although parts of the Labor Party stayed away from the government because they did not want to betray their pacifist convictions.

While the leading members of the Conservatives willingly put aside their own ambitions in forming a government and, in the interests of the cause, were content with lower posts in several cases, many members of the party’s base showed great ambition, resulting in fierce competition for the few available Post resulted. Bonar Law, who, despite his role as a conservative party leader, had been content with the post of colonial minister, was bombarded with letters in which ambitious supporters asked for a subordinate office.

By the end of 1916, Prime Minister Asquith was also the focus of criticism; Asquith, who despised the press, declined to associate with it and promote his cause. The powerful newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe , owner of The Times and Daily Mail , on the other hand, worked towards his removal. Asquith was known in the press on the one hand because of his exalted wife Margot (who had spent part of her school days in Berlin and was still openly Germanophile during the war), on the other hand because of his wait-and-see strategy, which he himself previously called "Wait and see" (Wait and see) had been harshly criticized. Asquith's political opponents, which included Edward Carson and Alfred Milner , accused him of weakness in decision-making and indifference; This, lengthy, protracted discussions and numerous internal intrigues made a quick decision-making process in the cabinet impossible. In contrast, Lloyd George acquired a reputation for energetic and energetic action as ammunition minister and subsequently as minister of war. Carson, Lloyd George and Bonar Law met in mid-November 1916 and subsequently pushed a petition: A smaller war cabinet, consisting of four people headed by Lloyd George, was to be formed, while Asquith was not to be a member.

Asquith refused to accept this, whereupon Lloyd George submitted his resignation. However, since Bonar Law supported Lloyd George and threatened the resignation of all Conservative ministers, Asquith saw no other viable option and resigned from his office. This decision led to the split in the Liberal Party. While Asquith, ousted as Prime Minister, went into the opposition with his supporters, a (smaller) part of the Liberals remained in the coalition under the new Prime Minister Lloyd George.

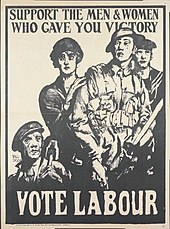

The “coupon election” in 1918

This coalition won the British General Election in 1918 , in which for the first time all men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30 had the right to vote. This election is also known as the “coupon election” - since the government had previously sent letters (coupons) to certain Liberal and Conservative politicians identifying them as supporters of the existing coalition. This exacerbated the already existing internal division in the Liberal Party and dealt it a severe blow. The coalition government won a clear majority in the election with the Conservatives as the main winner, while the Liberals under Asquith shrank to a rump party. The coalition liberals were also now clearly in the minority; the coalition consisted of three-quarters of Conservatives and one-fourth of Liberals on Lloyd George's side, while Asquith's Liberals had been replaced by the rising Labor Party as the leading opposition party. This had also left the coalition after the end of the war. In Ireland, the radical Sinn Féin party , which advocated the breakaway of Ireland from the United Kingdom and did not send any MPs to Westminster, won 73 seats for the first time at the expense of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party . The Irish Parliamentary Party, which had been allied with the Liberals in the lower house for many years, was all but wiped out in the election.

The difficult situation of the Liberals had also been exacerbated by the due reallocation of the constituencies, which took account of the new population distribution. Numerous seats, in which the Liberals traditionally won, had been dissolved and several new seats with a conservative majority had been created. Overall, the number of MPs in the lower house rose by 37; the new division gave the Conservatives in England, Scotland and Wales a total of 28 new seats in the lower house compared to the last lower house election in December 1910 , while the Liberals and Labor together only got a total of 8 new seats.

However, the new parliament not only differed considerably from its predecessor in terms of its relative party strength, the composition of the parties - especially the Conservatives - had also changed substantially. Businessmen, who often owed their prosperity to the war, were now strongly represented in the conservative parliamentary group. The conservative politician JCC Davidson , private secretary Bonar Laws and elected to the House of Commons in a by-election in 1920, described Lord Stamfordham , the secretary of King George V , that the old-fashioned gentleman of the country and the academic professions are hardly represented, but a high proportion of greedy, sober men would now have filled the ranks of the conservative party. Lloyd George also said on one occasion that he had the feeling that he was no longer speaking to the House of Commons, but to a Chamber of Commerce on the one hand and the Trades Union Congress on the other. The new group of conservative members of parliament showed little willingness to compromise and tended to see economic policy issues purely from the employer's perspective. In the social climate of the post-war period, in which profiteering was stigmatized in the face of the great victims of the war and the tensions between the social classes increased, this led to a loss of reputation for the coalition in the lower strata of the population.

Coalition government crises

The initial gratitude to David Lloyd George as "the man who won the war" had quickly given way to increasing disillusionment. The brief post-war economic boom in Great Britain had cooled off significantly by the end of 1920. By mid-1921, the number of unemployed had grown from an initial 300,000 to over two million people. There were a series of strikes by railroad workers and miners who (especially after the Russian Revolution ) fueled fear of Bolshevism . This and the associated fear of an increasingly strong Labor party that might drift into radical socialism was one of the main reasons for the increasingly reluctant adherence to the coalition government. The coalition was increasingly unpopular with the population, and several by-elections were lost for it. The main winner was the Labor Party, whose electorate was mainly fed by the working class and which was gradually able to consolidate itself as the leading opposition party. The Liberals, on the other hand, remained largely committed to their ideas (such as free trade and home rule) from the Victorian era and increasingly lost ground.

Many mistakes were personally blamed on Lloyd George, of whom the conservative backbenchers had harbored a strong suspicion for many years. Dissatisfaction also grew in the conservative local party organizations. This antipathy resulted partly from Lloyd George's leading role during the Parliament Act of 1911, but partly from his reputation for being a selfish politician who always put his own interests first. In particular, Lloyd George's foreign policy initiatives mostly turned out to be failures and were the subject of numerous internal disputes. The failure of the Genoa Conference and the Irish negotiations caused Lloyd George's prestige serious damage. In Genoa, Lloyd George was unable to achieve diplomatic success due to extensive differences between the German and French delegations and could not prevent the understanding between Germany and Russia that was achieved in Rapallo . While he himself viewed the Anglo-Irish Treaty as a personal success, the beginning of a terrorist campaign by Sinn Féins in the Northern Irish province of Ulster caused resentment among the Tories. The popular in large parts of the Conservative Party Andrew Bonar Law resigned for health reasons in March 1921 from the party chairmanship and resigned from the government; he was followed by Austen Chamberlain, who exercised nowhere near as close control over the backbenchers as his predecessor. Lloyd George relied on a tight circle of confidants in dealing with the Conservative Party and did not bother to advertise himself and his political concerns to the backbenchers.

In June 1922 a corruption scandal rocked the House of Lords ; Several times in the past few years men with dubious reputations had been ennobled, whose appointment was not considered permissible, but who had donated large sums to Lloyd Georges' agents. All parties have called for an investigation. Lloyd George had to, although he defended his practices, agree to the establishment of a royal commission in the House of Commons, which should deal in detail with the award of titles of nobility. Although Lloyd George had initially defused the matter, it added to the general anger of many Conservatives and marked a further step in the decline of the coalition. In July 1922 general discontent broke out in the Conservative Party. A group of junior ministers led by LS Amery confronted the coalition ministers with their request to end the coalition, but were haughty disgusted by Lord Birkenhead . In addition, Lord Salisbury played semi-publicly with some supporters with the idea of building an independent party to the right of the Conservatives. Salisbury had already played a leading role in the controversy over the Parliament Act of 1911 and, with around 50 supporters, formed the reactionary group known as "Die-hards", which still rejected many domestic political reforms that the liberals around Asquith and Lloyd had George in the period before the First World War. They opposed Lloyd George especially on the Irish question. At the beginning of August, Parliament adjourned to the usual summer recess.

As a result of the catastrophe in Asia Minor , the defeat of Greece in the war with Turkey , the Chanak crisis broke out in September 1922 , which again brought Lloyd George's foreign policy dilettantism into view . Lloyd George, Colonial Secretary Churchill and Lord Birkenhead single-handedly and without prior consultation with the Cabinet and Great Britain's allies, issue a statement threatening Turkey with war. The Conservative Foreign Minister Lord Curzon had to negotiate a compromise solution, the Mudanya Armistice , in difficult consultations . Curzon, who had been a regular victim of Lloyd George's biting ridicule in the cabinet and had often felt ignored, had more than once to correct his foreign policy mistakes. Curzon had submitted his resignation several times, but withdrew it again and again; after the Chanak crisis, however, he finally decided to resign, as he again saw himself duped by Lloyd George. In addition, the Chanak crisis exposed a schism in British politics that had existed for several decades , because since the days of Benjamin Disraeli the conservatives had been pro- Turkish on oriental issues such as the Bulgarian April Uprising, while the liberals had cultivated anti-Turkish resentment since Gladstone and were supporters of philhellenism .

In this situation, the temporarily recovered Andrew Bonar Law wrote a letter to the editor in the London Times , which was published on October 7th. He took the view that Great Britain could not act as the sole world policeman, as the financial and social conditions of the country would make this impossible. Numerous supporters of the Tories then asked Bonar Law to return to active politics.

On October 10, the cabinet agreed to schedule a lower house election and to contest it again together. The following day, Austen Chamberlain gave a speech in Birmingham in which he called for the coalition to be maintained in the face of the national crisis, otherwise the common enemy Labor would win. A day later, Lloyd George publicly defended his foreign policy, combined with an attack on Turkey, which he described as bloodthirsty; He also recalled that the Turks had already murdered thousands of Greeks and Armenians . On October 15, Chamberlain informed Conservative Chief Whip Leslie Wilson that he had decided to convene a meeting of all Conservative MPs to see their confidence as party leader. Chamberlain saw himself and his leadership circle as indispensable at this point and was convinced that his internal opponents would not be able to form another government.

The Carlton Club was chosen as the location ; Founded in 1832 by Tory Peers , this private London gentlemen's club was the traditional social meeting place for members of the Conservatives. In the mid-19th century, the Carlton Club had acted as the headquarters of the Conservative Party and on several occasions as the starting point for parliamentary initiatives Served by conservative backbenchers. In November 1911 he had been the scene of the election of Bonar Laws as the new party chairman, while in March 1921 Austen Chamberlain was unanimously elected to succeed Bonar Law at a meeting of the Conservative House of Commons held at the club.

Over the next few days, backbenchers from the Tories exchanged views at several informal meetings, in each of which a majority was against another coupon election and the resistance against the party leadership was already being coordinated; At one of these meetings, those present asked Sir Samuel Hoare , EG Pretyman and George Lane-Fox to see Bonar Law and persuade him to pull the party out of the coalition.

The role of Bonar Laws and the Newport by-election

Bonar Law has now been assaulted by several party friends to speak out for one of the sides. He hesitated for a long time, but finally agreed to attend the meeting. As a former party chairman, he played a key role because, apart from the unsteady Curzon, the other party leaders all voted to continue the coalition under the existing conditions and a newly formed government could only be formed by an experienced politician with high prestige. His open letter to the Times had already implicitly signaled that an alternative Conservative party leader and prime minister was ready.

In parallel to these events, there was a high-profile by-election in the Newport constituency. The conservative candidate, Reginald Clarry, one of the "die-hards", made his dislike for the coalition led by Lloyd George clear during his campaign appearances and openly mocked Lloyd George's "bumbling diplomacy" in a speech. While a victory for the Labor Party candidate was widely expected, the count on the evening of October 18 showed that Reginald Clarry, the Conservative candidate, had won the election, while the Liberal candidate was clearly beaten third. The influential London Times reported in detail on the front page of the by-election on the morning of October 19, classifying it as a complete condemnation of the coalition government and justification of those conservatives who spoke out against the coalition.

The meeting

The scheduled meeting began on October 19 at 11 a.m. with a large crowd of Conservative MPs. About 290 of them were present. Chamberlain grew cool, while Bonar Law was greeted with jubilation. Lord Birkenhead was greeted with loud expressions of discontent on his arrival. Chamberlain opened the meeting, criticizing that public criticism during the Chanak crisis had seriously damaged Britain's influence and prestige. He explained that the real conflict was not between liberals and conservatives, but between liberal forces and those who stood for socialism . It is impossible to win a majority against the Labor Party alone. Consequently, it is also madness to split the alliance with the Liberals at this point. Chamberlain's speech was received negatively by the majority.

Immediately after Chamberlain spoke the aspiring Stanley Baldwin . He criticized the cabinet decision on the next election, which had not been agreed with the party, threatened to resign from the government and to contest the upcoming election as an independent conservative candidate. Baldwin described Lloyd George as a dynamic force that could divide the Conservatives as much as the Liberals did before: "Take Mr. Chamberlain and myself. He is determined to venture into the political wilderness when forced to Let the Prime Minister down and I am prepared to go into the wilderness if I am forced to stay with him. ”Baldwin's speech met with much applause. It was followed by the deputy EG Pretyman, who spoke out against a continuation of the coalition; the current challenges can best be met through conservative principles. He introduced a resolution that the upcoming general election should be conducted as an independent party. This was supported by the next speaker, George Lane-Fox. FB Mildmay then spoke up with a conciliatory speech, whereupon Sir Henry Craik, one of the “die-hards”, also spoke out in favor of a break with Lloyd George's Liberals.

Then came Bonar Law, who warned against a continuation of the coalition and prophesied that otherwise there would be a split in the Conservative Party. In this situation, the unity of the party is more important to him than winning the next election. The feeling against continuing the coalition is now so strong that the party will split and a new party will be formed if Chamberlain's advice is followed. The moderate members would leave, the rest of the party would become more reactionary. He drew an analogy to the year 1846, when the dispute over the Corn Laws split the party: it would be a generation before the Conservative Party found its way back to the influence it deserved. The former party leader Arthur Balfour spoke out against the continuation of the coalition and called Pretyman's move dishonorable. Leslie Wilson, the Chief Whip and also a junior minister in the coalition, said that, following Chamberlain's statement, he still couldn't tell the electorate in his constituency whether there would be a Conservative Prime Minister in the event of a Conservative election victory. James Fitzalan Hope, a supporter of the coalition, suggested an adjournment, but Chamberlain pushed for an immediate decision.

The vote was held openly, with cards marked with the name of the MP. The result was clear, with 187 votes to 87 in favor of Pretyman's resolution. About a dozen of the MPs present had not cast a vote. A later analysis of the vote saw the coalition's strongest opponents in safe conservative constituencies, such as Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and especially Northern Ireland and London, where almost all MPs (present) voted against the coalition. The supporters of the coalition, however, were to be found in those contested constituencies where the Tories had to grapple with the Liberals, especially in Scotland, East Lancashire and the English south-west. The opponents of the coalition consisted of both the group of "die-hards" and the Tories, which are considered to be very moderate, such as Baldwin, Hoare and Edward Wood .

The Conservative Central Office , the headquarters of the Conservative Party, issued a detailed communiqué after the meeting, which the Times and other newspapers relied on in their reporting the following day. In this communiqué, only a casual remark by Andrew Bonar Law was left out at the end of the meeting, in which he admitted that he saw himself as an opportunist and was not in the least concerned about the destruction of the Liberal Party by David Lloyd George. The members of parliament present also gave an account of the meeting and their own voting behavior in their constituencies over the next few days.

Immediate aftermath

Immediately after the meeting, some Conservative cabinet members around Stanley Baldwin submitted their resignation to Prime Minister Lloyd George. Austen Chamberlain, however, first consulted with his supporters. Lloyd George drove to Buckingham Palace that afternoon and announced his resignation to King George V. In the expectation that no government could be formed against them, numerous well-known cabinet members - in addition to Chamberlain and Balfour, Lord Birkenhead, Sir Robert Horne and the Earl of Crawford - joined Lloyd George. The king then sent his secretary, Lord Stamfordham, to Bonar Law and invited him to form a new government. This initially refused with the formal note that he was not a party leader. On October 23, however, he was unanimously elected party leader of the Conservatives and, to the surprise of many observers, formed a new government over the next few days , relying primarily on Curzon as Foreign Minister and Baldwin as Chancellor of the Exchequer . To this end, he appointed several of those junior ministers and state secretaries from the previous government who had voted against the coalition. In addition, he appointed Lord Salisbury, the leader of the aristocratic right wing party, the "Die-hard" group, as Lord President of the Council ( Lord President of the Council ) in his cabinet. Since Chamberlain and his supporters had boycotted the formation of a government, Bonar Law's cabinet was made up of only a few experienced politicians. Winston Churchill, who was overthrown with Lloyd George, therefore disparagingly called the government “a government of the second eleven”.

Lloyd George attacked Bonar Law in the now beginning election campaign on his first appearance in Leeds; he called the Carlton Club meeting "a crime against the nation" and described it as a "reactionary meeting" that had been promoted from Mayfair and Belgravia (posh London neighborhoods where conservative high nobility and financial magnates had traditionally resided). Lord Birkenhead, who found himself largely isolated in his party, followed a little later in a similar way and called the meeting a revolt of the party machinery and of "second-rate minds" whose mediocrity frightened him. On the other hand, the Liberals under Asquith attacked the Conservative Party in the election campaign, but at the same time expressed satisfaction with the overthrow of Lloyd George. Bonar Law's election manifesto, on the other hand, promised a turn away from uncertainty and ruthlessness in foreign policy and a return to calm and stability in general government policy.

Historical significance

Due to the unstable and fluid situation in the British party landscape in the post-war years, contemporaries had actually expected the coalition to continue under changed conditions; However, the general election won by the Conservatives on November 15, 1922 led to stabilization and made a coalition government unlikely. As a result of the meeting, a split in the Conservative Party, which had previously been pursued by Salisbury and some supporters on the one hand, and Lloyd George (with the idea of forming a Center Party) on the other, was prevented. With the fall of the coalition, the previous British two-party system (with the Conservatives and the Liberals as antipodes) was replaced by a brief transition phase with three parties, in which the Liberals were increasingly ousted by the Labor Party as the leading opponent of the Conservatives. Lloyd George, one of the dominant politicians of the past decade, never held office again. Since then, the Liberal Party has never again provided the prime minister. The meeting marks the only time backbenchers toppled their party leader and the government. That is why it still occupies a prominent place in British party history to this day, and political reporting regularly refers to the meeting to emphasize the power of the conservative backbenchers.

The historian Robert Blake saw the Carlton Club meeting as a democratic process that expressed the lost trust not only of the Conservative MPs, but also broad sections of the party in Austen Chamberlain's leadership. A different vote would therefore have had a suspensive effect, because due to the prevailing mood in the party, a later party congress would ultimately also have resulted in Chamberlain's defeat. Michael Kinnear did not regard the meeting as a general rejection of a coalition, but merely as an expression of the Conservative Party's will to form a government in the event of a majority after the next election. Chamberlain's unsteady leadership decided the outcome of the Carlton Club meeting more than anything else; had the leadership of the conservatives remained firmly in the grip of Bonar Law after 1921, there would have been no break, according to Kinnear. John Campbell saw the outcome of the meeting as a corollary of the internal contradictions of the coalition and its unpopularity; the moment a real alternative appeared (with Bonar Law as Chamberlain's successor), it was brought down. It only took Bonar Law's return to active politics and Curzon's change of sides to rally the bulk of the Conservative party behind a new government. David Powell also saw the fall of the coalition as a result of the prime minister's unpopularity and the contradictions within the coalition. The meeting at the Carlton Club should be understood as a product of long-term tensions within the Conservative Party; in addition, the widespread distrust within the party against Lloyd George ultimately made the break of the coalition in its existing form inevitable. According to Powell, further cooperation with the Liberals would only have been possible through the previous removal of Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Research history

The Carlton Club meeting is very well documented and the subject of numerous publications, beginning with coverage in the UK press the following day. Numerous documents about the meeting can be found in the estate of various protagonists of the meeting; Above all, Austen Chamberlain's estate, which documents all requests to speak and a breakdown of the voting behavior of all participants in detail, is a valuable source. In the meantime, the diaries and memoirs of various participants can be used for evaluation, which results in a detailed picture.

Starting in the 1950s, the meeting was discussed in numerous biographies and memoirs. LS Amery published his three-volume memoir in 1953; in the second volume, My Political Life. Volume Two: War and Peace. 1914-1929. he devoted himself to the crisis of the coalition and its end, in which he had participated as Parliamentary Undersecretary and opponent of Lloyd George. In 1955, Lord Beaverbrook, as administrator of the estate, initiated Robert Blake's biography of Andrew Bonar Law. Beaverbrook published his book The Decline and Fall of Lloyd George in 1963 , in which he described how he witnessed Lloyd George's fall as a contemporary witness and marginally involved. Robert Rhodes James used 1969 as editor of the book Memoirs of a Conservative: JCC Davidson's memoirs and papers, 1910-37 his own listing of the voting behavior of the participants as a source, which shows some minor deviations compared to Austen Chamberlain's and Andrew Bonar Law's estate. (Davidson saw a final score of 185 votes to 88.)

Maurice Cowling described the decline of the coalition in his study The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics 1971 from the perspective of the appearance of the Labor Party as realistic competition to the two established parties. The challenge presented by Labor has led to the majority of the Conservatives opting to overthrow Lloyd George and then to position themselves as the main opponent of the Labor Party as defenders of the existing social order.

In 1973 Michaels Kinnear's book The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922 was published , which deals with the break of the coalition and the Carlton Club meeting. In it he also evaluated Chamberlain's estate in relation to the voting behavior of the MPs present and compared it to Davidson's records. Also in 1973 Chris Cook and John Ramsden published the book By-Elections in British Politics , in which John Ramsden in the chapter "The Newport By-Election and the Fall of the Coalition" the effects of the Newport by-election on the meeting and the fall of Coalition analyzed. In it he came to the conclusion that the result of the by-election was shaped by local characteristics, but the election victory of the conservative candidate Reginald Clarry had a major impact on the outcome of the Carlton Club meeting.

In 1977 John Campbell published the book Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922–1931 , a biographical study by David Lloyd George in the period from 1922 to 1931. The thesis of the book is the dominance of the politician and "phenomenon" David Lloyd George, who the political scene continued to dominate even after his fall as a result of the Carlton Club meeting; He also portrayed the coalition's domestic political achievements in a favorable light.

In 1979, the Welsh historian Kenneth O. Morgan published his book Consensus and Disunity - the Lloyd George Coalition Government 1918–1922 , in which he dealt in detail with the coalition government. Morgan argues that there were good reasons for the coalition to continue after the First World War and, contrary to its bad reputation, sought to rehabilitate the coalition at least partially.

In 1984 the historian John Vincent published the book The Crawford Papers: The journals of David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford and 10th Earl of Balcarres, 1871-1940, during the years 1892 to 1940 an edited version of the diaries of the Earl of Crawford . This also contains a detailed report on the meeting at the Carlton Club, which has been evaluated on various occasions by subsequent historians.

In 2004 David Powell published British Politics, 1910–1935: The Crisis of the Party System . He interpreted the years from 1910 to 1935 as a key phase in the political history of Great Britain and the increasing and violent party-political conflicts during this period as an immanent crisis in the British party system; He also dealt in detail with the coalition and the reasons for its break.

literature

- Robert Blake : The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955 (Reprinted 2010, ISBN 978-0-571-27266-2 ).

- Robert Blake: The Conservative Party from Peel to Major. Faber and Faber, London 1997, ISBN 0-571-28760-3 , pp. 184-211.

- John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape, London 1977, ISBN 0-224-01296-7 , pp. 17-46.

- Maurice Cowling: The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, ISBN 0-521-07969-1 , pp. 108-237.

- Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, ISBN 1-349-00522-3 .

- John Ramsden: The Newport By-Election and the Fall of the Coalition. In: Chris Cook, John Ramsden (Eds.): By-Elections in British Politics. Macmillan, London 1973, ISBN 1-349-01709-4 .

Web links

- The end of the 1922 coalition BBC Radio 4 discussion on the 90th anniversary of the Carlton Club meeting. BBC News, Oct. 28, 2012

- Alistair Lexden: The Carlton Club meeting and the fall of the Lloyd George Coalition Official Conservative Party historian Alistair Lexden on the Carlton Club meeting. Conservative Home, February 15, 2019

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 119 f.

- ^ Roy Jenkins : Mr. Balfour's Poodle. Bloomsbury Reader, London 2012, p. 221.

-

^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 70 ff.

Stephen Bates: Asquith (= 20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century ). Haus Publishing Ltd., London 2006, p. 68. - ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 227 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 242.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 243 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 253 f.

-

^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 294.

Stephen Bates: Asquith (= 20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century ). Haus Publishing Ltd., London 2006, p. 106. - ↑ Stephen Bates: Asquith (= 20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century ). Haus Publishing Ltd., London 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 162.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 302 ff.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 334.

- ↑ Stephen Bates: Asquith (= 20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century ). Haus Publishing Ltd., London 2006, p. 124 ff.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 179.

- ^ Maurice Cowling: The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, p. 23.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 73.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 52.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 412.

- ↑ John Campbell: Pistols at Dawn: Two Hundred Years of Political Rivalry from Pitt and Fox to Blair and Brown. Vintage Books, London 2009, p. 177.

- ↑ Gottfried Niedhart: History of England in the 19th and 20th centuries. CH Beck, Munich 1996, p. 154.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 414.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 415.

- ^ Maurice Cowling: The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, pp. 25 f.

-

↑ Stuart Ball: Portrait of a Party: The Conservative Party in Britain 1918–1945. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013, p. 479.

Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 4. - ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, pp. 63 ff.

- ^ Roy Hattersley : The Great Outsider. David Lloyd George. Abacus, London 2010, p. 550.

-

^ Hans Mommsen : Rise and Fall of the Republic of Weimar 1918–1933. Berlin 1998, p. 161.

Harold Nicolson: Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919–1925. A Study in Post-War Diplomacy. Faber Finds, London 1934, p. 269. - ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 436.

-

^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 31.

Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 119. -

^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 443.

Travis L. Crosby: The Unknown David Lloyd George: A Statesman in Conflict. IB Tauris, London 2014, p. 330. - ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 444.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 114.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 446.

- ↑ Harold Nicolson: Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919-1925. A Study in Post-War Diplomacy. Faber Finds, London 1934, p. 278.

-

^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 452.

Harold Nicolson: Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919-1925. A Study in Post-War Diplomacy. Faber Finds, London 1934, p. 279. - ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 446.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 448.

- ^ Roy Hattersley: The Great Outsider. David Lloyd George. Abacus, London 2010, p. 569.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 120.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 121.

-

^ Roy Hattersley: The Great Outsider. David Lloyd George. Abacus, London 2010, p. 571.

Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 122 f. - ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 451.

- ^ Seth Alexander Thévoz: Club Government: How the Early Victorian World Was Ruled from London Clubs. IB Tauris, London 2018.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Conservative Party from Peel to Major. Faber and Faber, London 1997, p. 137 ff.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 85 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 426.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 122 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 454 ff.

- ^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 26.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 122.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, pp. 456 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 457.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 126 f.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 127.

- ^ Roy Jenkins : Baldwin. William Collins, London 1987, p. 30.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 128.

- ^ Vernon Bogdanor: The Coalition and the Constitution. Hart Publishing, Oxford 2011, p. 78.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 129.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 130.

- ^ Roy Hattersley: The Great Outsider. David Lloyd George. Abacus, London 2010, p. 574.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The British Voter. Batsford, London 1968, pp. 104 f.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 129.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 458.

- ^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 39.

- ^ Maurice Cowling: The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, pp. 238 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 461 f.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 463.

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 464 ff.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 2.

- ^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 34.

- ^ David Powell: British Politics, 1910-1935: The Crisis of the Party System. Routledge, Abingdon 2004, p. 193 f.

-

^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 17.

Vernon Bogdanor: The Coalition and the Constitution. Hart Publishing, Oxford 2011, p. 76 ff. -

↑ 1922 and all that. The Guardian online, October 16, 2003, accessed February 27, 2019 . When the 1922 Committee comes calling, it's time to go. The Daily Telegraph online, October 17, 2012, accessed February 27, 2019 . How the 1922 Committee became the power behind a party. The Times online, October 17, 2018, accessed February 27, 2019 .

- ^ Robert Blake: The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life and Times of Andrew Bonar Law, 1858-1923. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London 1955, p. 458.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 133.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, p. 91 ff.

- ^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 29 f.

- ^ John Campbell: Lloyd George: The Goat in the Wilderness 1922-1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London 1977, p. 39.

- ^ David Powell: British Politics, 1910-1935: The Crisis of the Party System. Routledge, Abingdon 2004, p. 193.

- ^ David Powell: British Politics, 1910-1935: The Crisis of the Party System. Routledge, Abingdon 2004, p. 114 f.

- ^ Robert Rhodes James: Memoirs of a Conservative: JCC Davidson's memoirs and papers, 1910-37. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London 1969, pp. 130 ff.

- ^ Maurice Cowling: The Impact of Labor 1920-1924: The Beginning of Modern British Politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, p. 1.

- ↑ Michael Kinnear: The Fall of Lloyd George: The Political Crisis of 1922. Macmillan, London 1973, pp. 221 ff.

- ^ John Ramsden: Newport and the Fall of the Coalition. In: Chris Cook, John Ramsden (Eds.): Byelections in British Politics. Macmillan, London 1973, pp. 14-43.

- ^ David Powell: British Politics, 1910-1935: The Crisis of the Party System. Routledge, Abingdon 2004, pp. 2 ff.