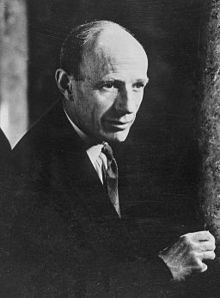

Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax KG , OM , GCSI , GCMG , GCIE , PC (born April 16, 1881 in Powderham Castle , Devon , England , † December 23, 1959 in Garrowby Hall , Yorkshire , England), between 1925 and 1934 also known as Lord Irwin and from 1934 to 1944 as Viscount Halifax , was a British politician of the Conservative party . From 1922 he held various ministerial offices and was Viceroy of India from 1926 to 1931 . In the 1930s he became one of the staunch advocates of the appeasement policy towards Nazi Germany , for which he was responsible as Foreign Minister from 1938 . His inner-party rival Winston Churchill pushed him at the end of 1940 to the post of ambassador to Washington for the duration of World War II .

Life

Origin and early career

Edward Wood, who later became Lord Halifax, was the fourth son of Charles Wood, 2nd Viscount Halifax . His West Country family was marked by illness and death. Three older brothers died in childhood, so that he finally inherited his father's title of Viscount . Halifax itself was born with a crippled left arm without a hand. Thanks to a prosthesis that he learned to use very skillfully, this disability did not affect his ability to ride, hunt, or shoot. Winston Churchill later nicknamed him "Holy Fox", an allusion to his name, his passion for hunting and his religiosity, since Halifax, like his father, was a devout Anglo-Catholic .

In Eton College and at Christ Church College trained, Wood belonged from 1910 to 1925 as a member of the constituency Ripon the lower house of. After receiving the peer rating , he moved to the House of Lords . As a young officer in the Yorkshire Dragoons, despite his disability, he took part in the First World War for a while . But he mostly stayed in the stage and took over a desk job in 1917. In 1918 he wrote the book " The Great Opportunity " with George Ambrose Lloyd , later Baron Lloyd . In it he championed the program of a reformed Conservative Party for the period after the war coalition led by the liberal David Lloyd George .

The coalition government planned to appoint Wood governor-general in South Africa , but Dominion leaders turned him down because they wanted a cabinet minister or a member of the royal family . At the same time, Winston Churchill, at that time still a member of the Liberals and a friend of Lloyd Georges, rebuked Wood because of his ambitions for the post of Secretary of State for the colonies. The disgruntled Wood therefore voted at the Carlton Club meeting in October 1922 for the overthrow of the Lloyd George cabinet and in 1922 became Minister of Education in the cabinet of the Conservative Andrew Bonar Law . Although he was not interested in this post, he kept it until 1924. Then he held the post of Agriculture Minister in the Conservative Cabinet Stanley Baldwin until 1925 with just as little commitment . His career seemed to have hit rock bottom.

Viceroy of India

Between 1926 and 1931, Wood succeeded Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading Viceroy of India. He was proposed in 1925 on the recommendation of King George V , probably because of his family background (his grandfather was India's minister) and his aristocratic origins. Raised Baron Irwin , he arrived in Bombay on April 1, 1926 with the hope of improving British-Indian relations and calming tensions between the various religious groups in the country. As a deeply religious person, he seemed the right choice to deal with Mahatma Gandhi . However, for the first 19 months of his calling, he ignored Gandhi.

His reign was marked by a period of great political unrest. The exclusion of Indians from the Simon Commission , who had to examine the country's maturity for self-government, provoked serious violence and so Wood was forced to concessions that were perceived as too extensive in London and half-hearted in India. During his reign he had to deal with various events such as the protest against the Simon Commission report, the Nehru report , the all-party conference, the 14 points of the head of the Muslim League Mohammed Ali Jinnah , the second civilian campaign led by the Indian National Congress Disobedience under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and the Round Table Conferences on the Future of British India .

As a strategy, Wood had all the leaders of Congress arrested and then opened negotiations with Gandhi. The criticism of Wood wasn't exactly fair, but he'd made a mistake the consequences of which were grave and the unrest grew. Wood tried to come to a modus vivendi with the Indian politicians ; this culminated in his advocacy of Dominion status . London refused any concessions.

With little room to maneuver, Wood fled into repression ; Using his emergency powers to arrest Gandhi, he banned public events and suppressed the rebellious opposition. Gandhi's arrest made things worse. Ultimately, Wood decided (by signing the Delhi Pact ) in January 1931 to negotiate, in which all interests were represented at the round table conference, to end civil disobedience and the boycott of British goods. The two-week discussions culminated in a treaty known as the Gandhi-Irwin Pact , which suspended the civil disobedience campaign.

The contract between Gandhi and Wood was signed on March 5, 1931. Decisive points were:

- Congress no longer continues the civil disobedience movement.

- The Congress takes part in the Round Table Conference.

- The government withdraws all orders to curb Congress.

- The government ends all non-violent criminal prosecutions.

- The government releases all those sentenced to prison terms in connection with their participation in the Campaign for Civil Disobedience.

It was also recognized that Gandhi attended the second round table conference as the sole representative of Congress.

Lord Irwin paid tribute to Gandhi's honesty, sincerity and patriotism on March 20, 1931 (at a dinner given by the reigning princes). A month after the Gandhi-Irwin Pact, he resigned and left India. When Irwin returned to England in April 1931, the situation was calm, but within a year the conference collapsed and Gandhi was arrested again.

Representative of the appeasement policy

In 1931, Wood turned down the offered office of Secretary of State to spend some time at home, but inexplicably followed in 1932 by his resurgence as Minister of Education in the cabinet of Labor Party Chairman Ramsay MacDonald , an office he enlivened with his continued role (now in the background) in Indian politics and legislation, obtaining the post of Master of the Middleton Hunt in the same year and his election as Chancellor of Oxford University in 1933.

In 1934, after the death of his father, he inherited the title of Viscount Halifax . In the following years he was a member of the Cabinet in various offices: five months in 1935 Minister of War, from 1935 to 1937 Lord Seal Keeper - at the same time he was President of the House of Lords - from 1937 to 1938 Lord President of the Council (the fourth highest office under the monarchy in terms of protocol) in Baldwin's cabinet and, after 1937, the Chamberlain cabinet .

Anthony Eden's appointment as Secretary of State in 1935 initially seemed to fit well with Halifax's views on the future direction of British foreign policy, which he increasingly interfered with with advice. The two were on the best of terms (also with the prevailing public opinion in Great Britain) that the German remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936 - " their own backyard " - did not pose a serious threat and was welcomed insofar as it was Germany's apparent progress towards it Normality after the tribulation resulting from the Versailles Peace Treaty . Nevertheless, after he succeeded Baldwin as the new Prime Minister in 1937, Chamberlain increasingly used covert channels, including Halifax itself, to conduct diplomacy.

Halifax's friend Henry (Chips) Channon later reported on Halifax's first visit to Nazi Germany in 1936: “ He told me that he liked all the Nazi leaders, even Goebbels , and he was very impressed, interested and amused by the Visit. He thinks the regime is absolutely fantastic . ”In his diary, Halifax noted that he told Hitler:“ Although there was much about the Nazi system that deeply offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) was up to Germany had done and what, from this point of view, it had achieved by sweeping communism out of its country . "

At the invitation of Hermann Göring , Halifax came to Germany in November 1937. The pretext was a hunting show, but Halifax had been given strict instructions from the Foreign Office in the event of a meeting with Adolf Hitler . According to some eyewitnesses, Halifax almost caused an international incident when he gave the dictator his coat on the assumption that it was a servant. Hitler later judged his visitor in his “dialogues in the Führer headquarters” as “ a hypocrite of the worst kind and lying ”. In the ensuing discussions, Halifax disregarded Eden's directive to warn the Germans about steps against Austria and Czechoslovakia . On the contrary, he indicated that Great Britain would not stand in the way of a clarification of the German territorial claims, also with regard to Danzig , provided that these were achieved by peaceful means. He was also forced to listen gently to Hitler's hair-raising advice on how to deal with the problems in India (" Shoot Gandhi "). The meetings were generally uncomfortable. Von Göring, a passionate hunter who had promoted himself to “ Reichsjägermeister ”, gave him the nickname “ Halalifax ” in reference to the hunters' Halali.

Failure as Foreign Minister

Halifax and Chamberlain were both known as Cliveden clique of, named after the estate of Lady Astor , where they met and the appeasement voted against Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was increasingly annoyed by the persistence with which Chamberlain meddled in his portfolio and - supported by Halifax - pursued the appeasement, particularly against Benito Mussolini . Eden, who saw Mussolini as an unreliable gangster, resigned from his position on February 20, 1938. Halifax became his successor. Three weeks later Austria was annexed to Nazi Germany. Czechoslovakia, until then relatively well protected against an attack by the German Reich by its fortifications in the Sudetenland along the common border, now saw itself seriously threatened. Because the fortress belt was easy to circumvent over Austria.

Halifax's handling of the crisis earned him great criticism. British foreign policy assumed that European dictators were generally honorable, reasonable and averse to a general war on the continent. All three hypotheses turned out to be false. The next result of this serious misjudgment was the downfall of Czechoslovakia, its military and its (armaments) industry, which Nazi Germany was able to incorporate without a shot being fired. After the Munich Agreement , in which Czechoslovakia first had to cede the Sudetenland, President Edvard Beneš protested that he had been presented with a fait accompli without even having been invited to the Munich Conference. Chamberlain had replied that Britain would not go to war over the Sudetenland. Halifax had serious doubts as to whether this would not lead to a complete break-up of Czechoslovakia , which actually took place in March 1939. However, out of justified concern that the British military was not ready for war with Germany, he made no effort to change British foreign policy. He allowed Chamberlain to sideline him at the fruitless conferences in Berchtesgaden , Godesberg and Munich and to attend them without him.

Further failures made the situation worse: on April 7, 1939, the Italian occupation of Albania took place , in the same month Hitler terminated the German-British naval agreement concluded in June 1935 , and on May 22, 1939 Italy and Germany signed the steel pact in which both parties Powers obliged to give unrestricted support in the event of war. The Hitler-Stalin Pact , which led directly to World War II , was also preceded by misjudgments by the Western powers Great Britain and France . Since the beginning of the 1920s, their policy was aimed at excluding the Soviet Union from settling central European disputes. Therefore they had long ignored Stalin's efforts to bring about a common front against the Third Reich . Although they concluded a provisional agreement with the Soviet Union at the end of July 1939, efforts to establish a supplementary military agreement were unsuccessful. Halifax only realized when it was too late that Moscow had been negotiating intensively with Berlin at the same time. On September 1, 1939, for example, he had to experience how the international structures he had tried to preserve disintegrated with the German attack on Poland . Previously, Hitler had promised a comprehensive settlement of German-British relations in the event that Great Britain gave Hitler a free hand with Poland. At the same time, however, Hitler had already given the order to attack Poland.

Chamberlain's controversial peacetime policy and his unsuccessful warfare until the spring of 1940 forced him to resign on May 9th. Halifax was considered a relatively popular candidate for his successor, but he announced on the same day that he would not be considered as prime minister because as a member of the House of Lords he could not lead government during a war. Even more serious was the fact that it was not acceptable to the Labor Party, which, in view of the dire war situation, was to be persuaded to join an all-party government of the national coalition. The Labor leadership insisted on Winston Churchill as head of government because he had vehemently opposed the appeasement early on and was considered an uncompromising opponent of Hitler. Churchill took office on May 10, 1940. Although conservative, the new prime minister had little support from his own parliamentary group. This continued to be mostly behind Chamberlain and Halifax. Churchill therefore kept both in government, Chamberlain as Lord President .

However, this did not remove the conflicting political assessments. When the collapse of the Netherlands , Belgium and France became apparent at the end of May 1940, after the rapid advance of the German Wehrmacht in the western campaign , Halifax brought the possibility of a peace of understanding with Nazi Germany into play. He believed that through Mussolini's mediation an agreement with Hitler would be possible, which would allow Hitler to rule over Western Europe, but leave the Empire its independence and integrity. A corresponding request to Mussolini should be made before the threatened annihilation of the British expeditionary forces , which were encircled in the Battle of Dunkirk , in order to still have a bargaining chip during negotiations. Churchill, on the other hand, considered the suggestion of willingness to negotiate with Hitler to be a big mistake, since this would make the weakness of his own position obvious and would almost challenge a German invasion of Great Britain. He called for the largest possible number of troops to be evacuated from Dunkirk and, if necessary, to continue fighting without France. The historian John Lukacs regards the fact that Churchill's uncompromising stance finally prevailed against Halifax as a decisive turning point in World War II. Hitler never came as close to victory as he did at the end of May 1940.

The successful evacuation of the troops from Dunkirk and the successful defense of Great Britain in the Battle of Britain brought about the final change of opinion in the public and in Parliament in favor of Churchill and his position. In August 1940, Halifax itself justified Hitler's rejection of a vague peace offer in a speech in the lower house. As a foreign politician failed anyway, Halifax was no longer needed to keep the conservative parliamentary group on Churchill's side.

Labor MP Aneurin Bevan said in a House of Commons meeting on November 5, 1940: “The Foreign Office has had a long series of uninterrupted disasters for 10 years. It is the worst Department in the Government, and that is saying a great deal because some of them are pretty bad. " - “The Foreign Office looks back on a series of uninterrupted disasters over the past 10 years. It's the worst of all the ministries in this government, and that is saying something because some of them are pretty bad. ”Halifax was replaced as Secretary of State on December 22, 1940 by his predecessor, Anthony Eden.

Halifax and the German Resistance

In his Halifax biography, Andrew Roberts discusses the foreign minister's late policy change. The struggle for peace, so tangible in Halifax's diplomacy at the outbreak of war, had been so deeply disappointed by Hitler's adventurism that he was largely immune to later peace offers. As evidence, Roberts argues that Halifax also rejected the initiatives taken by Pope Pius XII. , the Dutch and Belgian monarchs and not least the US President Franklin D. Roosevelt : He was convinced that the support of Hitler by the Germans at the beginning of the war was too overwhelming and that without the complete discrediting of the dictator any peace settlement would be worthless.

Other historians, on the other hand, point out that from autumn 1939 to 1943 the Foreign Office had offers submitted to the German resistance via the Vatican that included a territorial expansion of Germany beyond the borders of 1938: The conservatives in the German resistance around Carl Friedrich Goerdeler , Colonel General Ludwig Beck , Admiral Wilhelm Canaris , Johannes Popitz , von Hassel and Adam von Trott zu Solz sought - like the democratic politicians of the Weimar Republic - a revision of the Versailles Treaty and the resumption of the German Empire in the concert of the European powers. According to their ideas, this included the restoration of Germany's eastern borders from 1914 including the elimination of the Polish corridor , the incorporation of Austria, South Tyrol and the Sudetenland, German hegemony in the Balkans and a share in European colonial property. At a meeting on January 8, 1940 with Lonsdale Bryans , the contact person for Ulrich von Hassell , the foreign policy expert of the conservative German resistance, Halifax is quoted as saying that “he would be 'personally' against if the Allies emerged from a revolution in Germany wanted to gain advantages by attacking the Siegfried Line ... “if this would bring a regime to power that was ready to negotiate.

This line towards the German resistance was repeated in the exploratory efforts of Pope Pius XII. on June 28, 1940 regarding the conditions for a peace mediation, which Halifax rejected rather brusquely on July 22, 1940 only in the event of a negotiable (German) government. In July 1940, Halifax initiated the Foreign Office's strict rejection of German peace feelers by the Apostolic Nuncio in Bern , the Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar in Lisbon and the Finnish Prime Minister a few weeks before his position on the Pope's “cautious and half-baked” proposals.

Ambassador to the US and later years

Winston Churchill and Lord Halifax were very opposing characters and did not maintain a close relationship. Churchill kept his predecessor's foreign minister in office for seven more months to demonstrate the unity of the Conservative Party and government during the time of Britain's greatest threat. Churchill made Halifax British ambassador to Washington, probably also to get rid of his former rival . He had already dealt with Samuel Hoare , another member of the Cliveden clique, whom he had deported to the post of ambassador in Spain .

In December 1940 Churchill wrote to Roosevelt:

"I have now decided to ask for your formal agrément to the appointment of Lord Halifax as our Ambassador to the United States. I need not tell you what a loss this is to me personally and to the War Cabinet. I feel however that the transaction of business and the relationship between our two countries, and also the contact with you, Mr. President, are of such supreme consequence to the outcome of the war that it is my duty to place at your side the most eminent of my colleagues, and one who knows the whole story as it unfolds at the summit. "

In the US, Halifax initially proved clumsy. He made a number of widely publicized missteps, including some poorly received baseball jokes . He appeared to the American public as a distant, aloof British aristocrat , which he probably was. Relations, especially with President Roosevelt, gradually improved, but Halifax only played a minor role in Washington, as Churchill used close personal contacts in the United States. Once again, Halifax was sidelined by its prime minister and often excluded from sensitive discussions. As an old man mourning the death of his middle son on the front lines in 1942, Halifax Washington felt sick and asked Anthony Eden to replace him. In the end, however, he remained in his post until the term of office of the successors of Roosevelt and Churchill, President Harry Truman and Prime Minister Clement Attlee . When the US abruptly suspended supplies at the end of the war due to the lending and leasing laws on which the British economy depended, Halifax failed to find a solution that was beneficial to Britain. The following loan negotiations were also strained and ended unsatisfactorily for the UK.

His participation in a large number of international conferences was more successful. From April 25 to June 26, 1945, he took part in the Conference of San Francisco , which led to the establishment of the United Nations , at the first meeting of which he represented Great Britain. In his memoirs, he described the Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov as a “ smiling granite ”, but again he believed that Churchill, who coined the term “ Iron Curtain ” at the same time , overestimated the threat posed by this new global opponent. Halifax's autobiography The Fulness of Days , published in 1957, also suggests that he refused to learn from the mistakes of the 1930s.

The previous Viscount was elevated to Earl of Halifax in 1944 . After retiring from active politics in 1946, he almost only took on honorary posts such as Chancellor of Sheffield University , Chancellor of the Order of the Garter and Chairman of the BBC . He died just before Christmas 1959 on his Garrowby Hall estate.

Afterlife

Posterity will remember Lord Halifax primarily as a representative of the failed British appeasement policy towards Nazi Germany and as Churchill's internal party opponent. Halifax's policies and motivations are controversial to this day.

In the novel The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as in the 1993 film What Was Left of the Day , based on it, echoes the dilemma of the appeasers who, in a sincere effort to keep the peace, only made war all the more likely. In the film, Halifax is portrayed by Peter Eyre . The movie drama The Darkest Hour from 2017, which takes place in the decisive war days at the end of May 1940 and whose portrayal is based on John Lukacs, depicts the contrast between Churchill and Halifax, embodied here by Stephen Dillane . Richard Attenborough painted a more positive picture in 1982 in the film Gandhi . Sir John Gielgud is seen in the role of compromise Halifax, who was Viceroy of India as Lord Irwin.

Individual evidence

- ↑ John Lukacs: Five days in London. England and Germany in May 1940 , Siedler-Verlag, Berlin 2000

- ↑ www.nationalchurchillmuseum.org

literature

- Autobiography - Fullness of Days , Collins, 1957

- Alan Campbell-Johnson: Viscount Halifax: A biography , R. Hale, 1941

- Frederick Winston Furneaux Smith: Earl of Halifax: the life of Lord Halifax , Hamilton, 1965

- John Lukacs : Five days in London . England and Germany in May 1940 , Siedler-Verlag, Berlin 2000

- Andrew Roberts : * The Holy Fox: A Biography of Lord Halifax . Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1991. ISBN 0-297-81133-9 .

Web links

- Newspaper article about Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax in the 20th Century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- A bibliography of his tenure as Viceroy of India

- A website about his tenure as Viceroy of India

- Short biography of Lord Halifax (in English)

- Literature by and about Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax in the catalog of the German National Library

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Victor Bulwer-Lytton |

Viceroy of India 1926–1931 |

George Joachim Goschen |

| New title created |

Earl of Halifax 1944-1959 |

Charles Wood |

| Charles Wood |

Viscount Halifax 1934-1959 |

Charles Wood |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wood, Edward, 1st Earl of Halifax |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wood, Edward Frederick Lindley, 1st Earl of Halifax; Viscount Halifax; Baron Irwin; Lord Irwin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British politician, Member of the House of Commons, Viceroy of India and British foreign policy maker |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 16, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Powderham Castle , Devon , England |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 23, 1959 |

| Place of death | Garrowby Hall , Yorkshire , England |