Charlotte of Belgium

Marie Charlotte Amélie Augustine Victoire Clémentine Léopoldine of Belgium , later Carlota of Mexico , (born June 7, 1840 in Laeken Castle near Brussels ; † January 19, 1927 in Bouchout Castle in Meise ) was a Belgian princess and through her marriage to Maximilian I. Archduchess of Austria and Empress of Mexico .

Childhood and youth

She was born in Laeken , Belgium, the only daughter of Leopold I , King of the Belgians, and his second wife, Louise of Orléans , Princess of France . It was named after the first wife of her father, the English heir to the throne Charlotte Auguste , who died only a few hours after a stillbirth. Charlotte came from the German house of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha through her father, the first king of the Belgians . Thus she was both a direct cousin of Queen Victoria and of her husband Albert von Sachsen-Coburg and Gotha . Her mother died when she was only ten years old. Since then she has become her father's favorite. Even when she was born she was considered one of the richest princesses in Europe.

Marriage to Archduke Maximilian, Empress of Mexico and widowhood

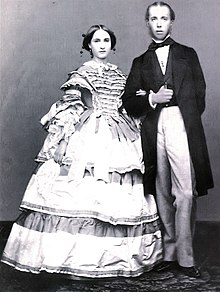

Charlotte was sixteen when she first met Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian , the idealistic and liberal younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph , and fell in love with him. Tough negotiations ensued over the bride's dowry . Finally, a trousseau tax of 535,000 francs in jewelry and 2,874,000 francs in securities was set. The couple married on July 27, 1857 in Brussels. Later they both moved to Trieste , where Max had Miramare Castle built on the Bay of Grignano according to his wishes .

In the years 1862/63 , French intervention troops entered Mexico and drove out the Republican government. After Maximilian, due to false promises on the part of Napoleon III. and at the insistence of his wife Eugénie , who accepted the Mexican crown on April 10, 1864, the couple moved into the neo-Gothic Chapultepec Palace on a hill on the outskirts of Mexico City . Charlotte became Empress of Mexico under the name Carlota . A lifelong dream had come true for her - she was Empress. However, Maximilian had already rejected the throne of Greece that had been offered to him - his cousin, Otto of Greece , and his wife Amalia had previously been driven out by him.

When Napoleon III. With his troops withdrawn from Mexico and Maximilian alone in the struggle against the revolutionary movements, Charlotte traveled to Europe to ask the Pope for support in Paris , Vienna and finally in Rome . Their efforts were unsuccessful. She suffered a severe nervous breakdown and never returned to Mexico. After Maximilian's execution in 1867, her condition worsened and her brother Philipp , Count of Flanders, consulted doctors for assessment; among these also the psychiatrist Josef Gottfried von Riedel , who they declared insane. She spent the rest of her life very withdrawn, first at Miramare Castle and then at Bouchout Castle in Meise, Belgium, where she died on January 19, 1927. It is said that until her death she believed she was the reigning Empress in Mexico. She is buried in the Liebfrauenkirche in Laeken.

progeny

Charlotte and Maximilian had no children. In 1865, however, the couple adopted Agustín de Iturbide y Green and Salvador de Iturbide y Marzán , grandsons of Agustín de Iturbide , the former emperor of Mexico who ruled between 1822 and 1823. Agustín was given the title of "His Highness the Prince of Iturbide" at the age of two, in order to be able to use him as heir to the throne. The events of 1867 dashed such hopes, however, and when Augustín was of age, he renounced all rights to the throne, served in the Mexican Army, and eventually established himself as a professor in Washington, DC

Some claim that Charlotte gave birth to an illegitimate child on January 21, 1867, to the Belgian Colonel Alfred Baron van der Smissen . That would mean Charlotte was pregnant when she sailed to Europe in search of support for her husband. According to some sources, this child was the future French General Maxime Weygand (1867–1965). Weygand refused to comment on these rumors, and his parents' identity remained unresolved. Other sources claim that his mother is an unknown Polish woman and that his father Leopold II (Charlotte's brother) or Maximilian. The Belgian historian André Castelot , however, believed that van der Smissen was Weygand's father, but could not prove it.

Character and personality

Charlotte was considered very well educated in her day - she was fluent in four languages and was taught in philosophy, history, science, music and painting by Peter Ludwig Kühnen . She also loved the music of Johann Sebastian Bach . She was a distinct beauty that even rivaled Sisi . But she was precocious and always seemed superior. Like her future husband, she was always convinced that she was destined to rule. Contemporaries and many historians saw in her an ambitious woman who had plunged the good-natured dreamer Maximilian into disaster because of her lust for power. However, the strong-willed woman's love for her romantic husband was greater than the reverse. During the negotiations regarding her dowry it was already clear that he was much more a businessman than a dreamer in love, since he had already amassed huge debts, and her fortune could help him out of this distress.

literature

- André Bénit, Charlotte, princesse de Belgique et impératrice du Mexique (1840–1927). Un conte de fées qui tourne au délire ... Essai de reconstitution historique , Plougastel, Historic'one Editions, 2017, ISBN 978-2-912994-62-2 .

- André Bénit, “Charlotte de Belgique, impératrice du Mexique. Une plongée in the ténèbres de la folie. Essai de reconstitution fictionnelle », Mises en littérature de la folie , Çédille, Revista de estudios franceses , Monografías de Çédille 7, 2017, pp.13-54 (ISSN: 1699-4949).

- André Bénit, Legends, intrigues et médisances autour des “archidupes”. Charlotte de Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha, princesse de Belgique / Maximilien de Habsbourg, archiduc d'Autriche. Récits historique et fictionnel , Bruxelles, Peter Lang, Éditions scientifiques internationales, 2020, 438 pages, ISBN 978-2-8076-1470-3 .

- Erika Bestereiner : Charlotte of Mexico. Triumph and tragedy of an empress. Piper, Munich et al. 2007, ISBN 978-3-492-04681-7 .

- la Princesse Bibesco : Charlotte et Maximilien. Ditis, Paris 1962.

- André Castelot : Maximiliano y Carlota. La Tragedia de la Ambición. EDAMEX, México 1985.

- Egon Caesar Conte Corti : Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico . According to the previously unpublished secret archives of Emperor Maximilian and other unknown sources. 2 volumes. Amalthea-Verlag, Vienna 1924.

- Egon Caesar Conte Corti: The Tragedy of an Emperor. Maximilian of Mexico (= fisherman 34). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1953.

- Suzanne Desternes, Henriette Chandet: Maximilien et Charlotte. Perrin, Paris 1964.

- Curt Elwenspoek : Charlotte of Mexico. The suffering of an empress . A historical-psychological view of life based on new sources. With numerous unknown pictures and letters. Hädecke, Stuttgart 1927.

- Amparo Gómez Tepexicuapan: Carlota en México. In: Susanne Igler, Roland Spiller (eds.): Más nuevas del imperio. Estudios interdisciplinarios acerca de Carlota de México (= Latin American Studies 45). Vervuert et al., Frankfurt am Main et al. 2001, ISBN 3-89354-745-2 , pp. 27-40.

- Miguel de Grecia : La Emperatriz del Adiós. El trágico destino del emperador Maximiliano y su mujer Carlota. Plaza & Janés, Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-01-32810-1 .

- Bertita Harding: Phantom Crown. The story of Maximilian and Carlota of Mexico. Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis IN et al. 1934 (3a edición. Ediciones Tolteca, México 1967).

- Joan Haslip: The Crown of Mexico. Maximilian and his Empress Carlota. 2nd edition. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York NY 1972, ISBN 0-03-086572-7 .

- H. Montgomery Hyde: Mexican Empire. The history of Maximilian and Carlota of Mexico. Macmillan, London 1946.

- Susanne Igler: Carlota de México (= Grandes Protagonistas de la Historia Mexicana ). Planeta DeAgostini, México 2002, ISBN 970-726-080-7 .

- Susanne Igler: De la intrusa infame a la loca del castillo. Carlota de México en la literatura de su “patria” adoptiva (= studies and documents on the history of Romanic literatures 58). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55029-8 (also: Erlangen-Nürnberg, Univ., Diss., 2005).

- Mia Kerckvoorde: Charlotte. La passion et la fatalité. Duculot, Paris 1981, ISBN 2-8011-0358-6 .

- Karl Baron von Malortie: Mexican Sketches. Memories of Emperor Max. Greßner & Schramm, Leipzig 1882.

- Armando María y Campos: Carlota de Bélgica. La infortunada Emperatriz de México (= Vidas españoles e hispanoamericanas 10). Ediciones Rex, México 1944.

- Armand Praviel: La vida trágica de la emperatriz Carlota (= Colección Austral 21, ISSN 0069-5041 ). Espasa-Calpe Argentina, Buenos Aires 1937.

- Konrad Ratz (Ed.): “Passing away from longing for you”. The private correspondence between Maximilian of Mexico and his wife Charlotte. Amalthea, Vienna et al. 2000, ISBN 3-85002-441-5 .

- Hartwig Vogelsberger, (Ed.): Emperor of Mexico. A Habsburg on Montezuma's throne. Amalthea, Vienna et al. 1992, ISBN 3-85002-322-2 .

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Habsburg, Maria Charlotte . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 7th part. Imperial and Royal Court and State Printing Office, Vienna 1861, p. 43 ( digital copy ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Charlotte of Belgium in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Charlotte of Belgium in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- January 19, 1927 - Charlotte of Belgium, ex-Empress of Mexico dies

- Maximilian of Mexico: The woman at his side

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich Weissensteiner : Reformers, Republicans and Rebels. The other house of Habsburg-Lothringen (= Piper series 1954). Piper, Munich et al. 1995, ISBN 3-492-11954-9 .

- ↑ Konrad Kramar, Petra Stuiber: The quirky Habsburgs. Quirks and airs of an imperial house. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-8000-3742-4 .

- ↑ https://le-carnet-et-les-instants.net/2020/06/25/benit/

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Charlotte of Belgium |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Charlotte, Empress of Mexico |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Empress of Mexico |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 7, 1840 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Laeken Castle near Brussels |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 19, 1927 |

| Place of death | Bouchoute Castle near Brussels |