Codex Hammurapi

The Codex Hammurapi (also in the spelling Codex or Hammurabi and Ḫammurapi ) is a Babylonian collection of legal rulings from the 18th century BC. It is considered to be one of the most important and best-known literary works of ancient Mesopotamia and an important source of legal systems handed down in cuneiform ( cuneiform rights ). The text goes back to Hammurabi , the sixth king of the 1st Dynasty of Babylon . It is on an almost completely preserved 2.25 m high diorite stele , on several basalt stele fragments from other steles and in over 30 clay tablet copies from the second and first millennium BC. Chr. Handed down. This stele itself is also often referred to as the “Codex Hammurapi”. It is now exhibited in the Louvre in Paris and, like the fragments of the basalt stelae, was found by French archaeologists in Susa , where it was taken in the 12th century BC. Was abducted from Babylonia. Because of this good source situation, the text is fully known today.

The text consists of around 8,000 words, which were written in 51 columns with around 80 lines each in ancient Babylonian monumental cuneiform script on the preserved stele . It can be roughly divided into three sections: a prologue of around 300 lines, which explains the divine legitimation of the king, a main part, with 282 legal clauses according to modern classification, and an epilogue of around 400 lines, which praises the righteousness of the king and calls upon subsequent rulers to obey the legal principles. The contained legal clauses, which take up around eighty percent of the total text, concern constitutional law, real estate law, law of obligations, marriage law, inheritance law, criminal law, tenancy law, and cattle breeding and slave law.

Since its publication in 1902, Assyriologists and lawyers have primarily been concerned with the text, the situation of which it was created or its function ( seat in life ) has not yet been clarified. The original assumption that it was a systematic summary of applicable law ( legal codification ) was contradicted early on. Since then, it has been discussed whether it is a private legal record ( legal book ), model decisions, reform laws, a teaching text or simply a linguistic work of art. These discussions have not yet been concluded and are largely related to the professional and cultural background of the respective authors. The theology showed a strong interest in the Code of Hammurabi, and especially a possible reception of the same in the Bible was controversial.

Again and again the Codex Hammurapi is referred to as the oldest “law” of mankind, a formulation that can no longer be adhered to today - regardless of the controversies mentioned - since the discovery of the older codes of Ur-Nammu and Lipit-Ištar .

Lore history

The 3800-year-old text of the Codex Hammurapi is best known for the diorite stele in the Louvre (Département des Antiquités orientales, inventory number Sb 8) . This was found in the winter of 1901/1902 by Gustave Jéquier and Jean-Vincent Scheil during a French expedition to Persia led by Jacques de Morgan on the Acropolis of Susa in three fragments. As early as April 1902, they were reassembled into a stele and taken to the Paris Museum and their inscription was edited and translated into French by Jean-Vincent Scheil that same year. Scheil specified a paragraph numbering based on the introductory word šumma (German: "if"), which resulted in a total of 282 paragraphs for the text - a count that is still used today. In the same year, the first German translation followed by Hugo Winckler , who took over Scheil's paragraph division.

The stele exhibited in the Louvre shows a relief in the upper area , which shows King Hammurapi in front of the enthroned sun, truth and justice god Šamaš . Hammurapi assumes the arm position of a prayer, which is also known from other depictions, while the god presumably gives him symbols of power. Some researchers have also argued that the god depicted is more of the Babylonian city god Marduk . Below that, the text of the Codex Hammurapi is carved into 51 columns of around 80 lines each. The ancient Babylonian monumental script was used as the character , which is even more similar to the Sumerian cuneiform script than the ancient Babylonian cursive script, which is known from numerous documents from this period.

Part of the text on the stele was already chiseled out in antiquity; however, this can be reconstructed based on comparative pieces, so that today the entire text is known. This carving goes back to the Elamites who, under King Šutruk-naḫḫunte, abducted the stele along with numerous other works of art, such as the Narām-Sîn stele , to their capital in today's Iran during a campaign to Mesopotamia . The original location of the stele is therefore not known; however, reference is repeatedly made to the Babylonian city of Sippar . Nine other basalt fragments found in Susa indicate that at least three other steles with the codex existed, which were then probably set up in other cities.

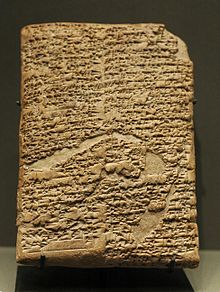

In addition to the main text in the form of the stele inscription, the Codex Hammurapi is also known from a number of clay tablets that quote parts of the text. Some of these were discovered as early as the 19th century, but some only after the stele was found in Susa. They are now in the British Museum , the Louvre, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia. As early as 1914, a large copy of §§ 90–162 was found on a clay tablet in the Philadelphia Museum, from which the ancient classification of the paragraphs emerges, which in some places deviates from the Scheil classification used today. Copies of the text also come from the following epochs and other regions of the Ancient Orient up to the Neo-Babylonian period, although the ancient "paragraph division" varied.

construction

The Codex Hammurapi follows the three-part division into prologue, main part and epilogue known from other ancient oriental legal collections. The prologue in the text of the stele from Susa comprises 300 lines, the epilogue 400 lines. In between is the main part of the text with the actual legal clauses and a volume of around 80% of the entire work.

prolog

According to prevailing opinion, the prologue of the Codex Hammurapi is one of the most important literary works of the ancient Orient. It can be divided into three sections, which are typical of the ancient oriental codes in this order:

- Theological part,

- Historical-political part,

- Moral-ethical part.

The theological part serves to explain Hammurapi's divine legitimation and is constructed as a long temporal sentence. In this it is first explained that the Babylonian city god Marduk was called to rule over humanity by Anu and Enlil , the highest gods of the Sumerian-Akkadian pantheon. Accordingly, Babylon, as his city, was also designated as the center of the world. So that there would be a just order in the country, that evildoers and the oppression of the weak would come to an end and that the people would be well, Hammurabi was then chosen to rule over the people.

A Neo-Babylonian copy of the prologue (BM 34914) shows that there were several variants of this text, whereby this Neo-Babylonian copy differs from the text version of the stele from Susa, especially in the theological part. In this version Hammurapi is empowered directly by Anu and Enlil, while Marduk is not mentioned. Instead of Babylon, Nippur is determined to be the center of the world and the mandate to rule goes directly from Enlil, the city god of Nippur. It may be a concession by the king to the religious center of Nippur.

This is followed by the historical-political part as a self-portrayal of the king with his political career, which is stylized as epithets in the form of a list of his deeds in cities and shrines . Since this list of cities corresponds to the cities that belonged to Hammurapi's empire in his 39th year of reign, this represents a term post quem for the dating of the stele from Susa. A clay tablet copy (AO 10327) contains another version of this list of cities, dating from the 35th. Government year can be assigned. From this it becomes clear that the stele does not contain the oldest version of the Codex Hammurapi. The only clue for an alternative dating of the text is the name of the 22nd year of the reign of Hammurapis mu alam Ḫammurapi šar (LUGAL) kittim (NÌ-SI-SÁ) (German: year - statue of Hammurapis as King of Justice). Since this stele is also mentioned in the text of the Codex Hammurapi and its existence is therefore assumed, the 21st year of the Hammurabi reign is used as an alternative term post quem .

The moral and ethical part follows the preceding one without establishing a geographical reference. So he first explains his affiliation with the founder of the dynasty Sumulael and his father Sin-muballit and refers to the management mandate issued by Marduk, which he followed by establishing law and order ( a.k.:kittum u mīšarum ). The end of the prologue is the word inūmīšu (German: at that time), which is then followed by the actual legal clauses .

Legal propositions

A large number of Assyriologists and lawyers were concerned with the actual legal propositions, who tried above all to grasp the systematic behind them and in this way to open up their nature. In the course of time, various approaches were presented, but due to various shortcomings they were not generally recognized. This is particularly true of the early attempts to create a system based on logical or legal-dogmatic aspects, such as those made by the French Pierre Cruveilhier .

One of the most important attempts of this kind was that of Josef Kohler , who initially correctly stated that the legal clauses at the beginning of the text are primarily characterized by a relationship to "religion and royalty". These should then be followed by “provisions on trade and change”, in particular agriculture, transport and the law of obligations, according to which there would have been regulations on family and criminal law before shipping, tenancy and employment relationships and servitude rounded off the text. David G. Lyon , in particular, turned against this with an alternative classification proposal. He assumed that the Codex Hammurapi was divided into the three main sections introduction (sections 1–5), things (sections 6–126) and persons (sections 127–282), with the section things in the subsections of private property (Sections 6–25), real estate, trade and business (from Section 26) would disintegrate and the section on persons into the subsections Family (Sections 127–195), Infringements (Sections 196–214) and Work (Sections 215– 282). This classification, which has already been contradicted several times, was later followed by Robert Henry Pfeiffer in order to be able to compare the Codex Hammurapi with biblical and Roman law. So he named §§ 1–5 as “ ius actionum ”, §§ 6–126 as “ ius rerum ” and §§ 127–282 as “ ius personarum ”, whereby the latter section is still in “ ius familiae ” ( Sections 127–193) and “ obligations ” (Sections 194–282).

In general, however, Herbert Petschow's attempt met with the greatest approval. He noted that the legal clauses were organized according to subject groups, which separated legally related norms from one another. Within individual subject groups, the arrangement of the legal clauses was based on chronological criteria, the weight of the treated goods, the frequency of the cases, the social status of the persons concerned or simply according to the case-counter case scheme. Petschow also succeeded in demonstrating that individual legal clauses were primarily arranged according to legal aspects; this includes the strict separation of contractual and non-contractual legal relationships . Basically, the Codex Hammurapi can be divided into two main sections according to Petschow:

Public order

The first 41 legal clauses concern the public sphere, characterized by royalty, religion and people. They can be further subdivided into several sections.

The first of these sections is made up of Sections 1-5, which deal with the persons who are significantly involved in the judicial process: plaintiffs, witnesses and judges. For this reason, Petschow gave this first section the heading “Realization of law and justice in the country” and saw in this a direct connection to the concern last expressed in the prologue. These five legal principles threaten false accusation and false testimony with punishments according to the principle of talion ; For judges who were corruptible, removal from the office of judge and a property penalty of twelve times the subject matter of the proceedings were provided.

The second section comprises Sections 6–25 and deals with “capital offenses” that are viewed as particularly dangerous by the public. These are primarily property crimes that are directed against public property (temple or palace) or against the social class of the muškēnu . There are also individual other criminal offenses that were either viewed as dangerous to the public or were sorted at this point due to attractions . All legal provisions in this section have in common that they provide for the death penalty for delinquents.

Sections 26–41 then form the third section, which deals with “official duties”. The official duties (akkadisch ilku ) are often inappropriately translated as fiefdoms , since the person obliged to perform his official duties normally performed on a property made available for this purpose. After the definition of penalties for breaches of duty of duty, rules are made on the whereabouts of the ilku property in the event of captivity or flight of the duty officer. Finally, a kind of legal transaction power of the duty-obligated person over his ilku property is established.

"Private law"

The remaining legal clauses mainly concern the individual sphere of the individual citizen. This larger group of legal propositions deals with property, family and inheritance law, but also with questions of work and physical integrity. Although they are clearly separated from the previous section by their composition, there is a connection in terms of content via the topic of "Agriculture".

Sections 42–67, which deal with “private property law ”, form the first section here ; namely fields, gardens and houses one after the other. At first, contractual legal relationships are dealt with, which takes place primarily in the form of regulations on lease and lien . This is followed by provisions on non-contractual liability for damage .

In these legal clauses, provisions on the “fulfillment of debt obligations” are inserted several times, which then becomes the dominant topic in §§ 68–127 and thus represents a new section. The main object of this is the tamkarum (merchant). In addition, there are also regulations on the sabītum (innkeeper) before this section is closed with the subjects of attachment and debt enslavement .

Sections 128–193 form a clearly definable section that deals with “marriage, family and inheritance law”. Here, the marital fiduciary duties of the woman, the maintenance and care duties of the husband and finally the financial effects of the marriage for both spouses are dealt with one after the other. This is followed by a series of criminal offenses in the sexual area, before finally the possibilities of dissolving a marriage and its financial consequences are dealt with.

This part is then followed by legal principles of inheritance law , with the dowry on the death of the wife and the property after the death of the family father being dealt with one after the other . In the case of the latter, a further differentiation is made between the inheritance law of legitimate children, the surviving widow and children of a mixed marriage. The inheritance law of daughters as a special case is separated from it by procedural provisions. This group of legal clauses is rounded off by adoption and legal provisions.

Another section, which essentially deals with “violations of physical integrity and damage to property”, consists of §§ 194–240. Here, too, contractual and non-contractual legal relationships are strictly separated from one another, whereby the legal relationships based on tort are dealt with first. As a rule, penalties are threatened according to the talion principle . Then bodily injuries and damage to property are dealt with, which were committed in the performance of contractual relationships, whereby provisions about the skillfully performed activity were always put in front. At the end of the section there are legal clauses that deal with questions of liability in connection with ship rental and thus represent a transition to the last section.

This consists of §§ 241–282 and deals with “livestock and service rent”. The legal clauses are sorted chronologically according to the chronological sequence of cultivation from the cultivation of the fields to the harvest. Within these groups, a distinction was made between contractual and non-contractual liability. General rental rates are set at the end of this section before the legal clauses end with provisions on slave law.

epilogue

The epilogue begins on the stele with a new column that sets it apart from legal clauses. It begins with the formula reminiscent of a colophon :

"Laws of justice which Ḫammurapi, the able king, established and (through which he) allowed the country to establish proper order and good conduct."

Success reports follow, some of which represent the fulfillment of the tasks mentioned in the prologue. In the epilogue, however, more detailed information about the stele itself is given. According to the Codex, this was set up in Esaĝila in Babylon in front of the "statue of Ḫammurapis as King of Justice". From this it is concluded by some authors that the stele found in Susa originally came from Babylon and not from Sippar.

This is followed by the Ḫammurapi's wishes for the realization of his justice, his own memory and for dealing with the relief. The passage used to interpret the Codex as legislation also comes from this section :

“A man who is wronged and who receives a case may come before my statue 'King of Justice' and have my written stele read to him and hear my lofty words and my stele show him the case. May he see his judgment "

At the end of the epilogue there are exhortations to future rulers to preserve and not to change the legal norms, which are affirmed with the wish for a blessing of the next ruler by Šamaš. This is followed by a long collection of cursing formulas, which take up most of the epilogue and are directed against any influential person who does not follow the admonitions. These curses also follow a fixed scheme, which consists of the name of the deity, its epithets , its relationship to Ḫammurapi and a suitable curse.

The Ḫammurapi stele

Compared to the text of the Codex Ḫammurapi, the stele found in Susa was only marginally the subject of further scientific research. This is not least due to the fact that experts did not attach any great importance to the representation at the head of the stele or denied it an artistic added value. On the other hand, Near Eastern archeology is traditionally oriented towards art history and therefore concentrated on style analysis, motive research and investigation of particularities with the aim of dating, so that predominantly descriptive, art-looking works were created, while cultural-historical interpretations of the stele remain the exception. The most cited attempt at such an interpretation was presented in 2006 by Gabriele Elsen-Novák and Mirko Novák .

The altogether 2.25 m high stele consists of black, glossy-polished diorite and has a 60 × 65 cm relief field at its upper end. On it is a shortened version of the so-called introductory scene known from the glyptic since the Ur III period : A male figure, Ḫammurapi, stands in front of an enthroned deity, Šamaš . A hand of the king is raised, which based on literary evidence can be associated with the adoration of deities. The Ḫammurapi stele stands out from other portraits from this period through the profile of the heads, which only has a parallel in the investiture of Zimri-Lim . As with the latter, the king is given a ring and a staff by the god, the interpretation of which has been controversially discussed. It is possible that the ring is a general Machtinsignie, while the rod a stylus could be.

Iconological considerations show that the relief attempted above all to portray the divine legitimation of the ruler publicly and to posterity.

Nature and function of the Ḫammurapi Codex

Since the publication of the text over 100 years ago, its nature and function have been controversially discussed in ancient oriental and legal history research. The Ḫammurapi Codex was discovered at a time when new civil codes, including the BGB in Germany, came into force in many European countries and the public awareness of the importance of comprehensive codifications of applicable law. Added to this was the temporal position of this text, which made it appear for a long time as the oldest legal work of mankind, which preceded the Roman Twelve Tables law by more than a millennium.

Scheil already interpreted the text he published as the “Code des lois de Hammurabi” (Code of the Ḫammurapi). As such, it was and is often treated as an example of early legal modifications based on the Talion principle . For this interpretation, it is said to this day that the Codex Ḫammurapi, according to the passage quoted above on the reverse, is a source of knowledge for those looking for law. In addition, it comes from a time in which there was a need for a uniform legal system throughout the empire as part of the establishment of the Old Babylonian Empire, and should therefore be seen as a legislative reform. This is also supported by the fact that process documents ultimately correspond to the views of the Codex Ḫammurapi. This could at least lead to the conclusion that the Codex contained the law applicable at the time. Depending on the focus of the author, the text is referred to as an enacted law , reform law or legal code , possibly also in the sense of a collection of royal legal decisions.

The Assyriologists Wilhelm Eilers and Benno Landsberger first expressed doubts about this interpretation in the pre-war period, which started the controversy that has not ended to this day. This criticism can be based in particular on the fact that the norms named in the Codex do not correspond to contemporary contracts, the Codex is also not cited as a legal source in any of the numerous legal documents and it is only eclectic in character. What is striking, however, is the widespread use of the text in writing schools, which could indicate that the codex was primarily a linguistic work of art. In addition, the text was written remarkably late in the 20th year of the king's reign. Together with the artistic design and the valuable material, this could speak for the purely monumental character of the stele. The text carved on it could have served primarily the king's propaganda.

literature

- Godfrey Rolles Driver, John C. Miles: The Babylonian Laws. Volume 1: Legal Commentary. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1952; Volume 2: Text Translation. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1955; New edition: Wipf and Stock, Eugene (OR) 2007

- Jan Dirk Harke : The sanction system of the Codex Ḫammurapi (= Würzburg juristic writings 70 ). Wuerzburg 2007.

- Heinz-Dieter Viel: The Codex Hammurapi . Cuneiform edition with translation. Dührkohp & Radicke, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-89744-213-2 .

- Wilhelm Eilers : Codex Hammurabi . the law stele of Hammurabi. Marix, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-86539-203-9 (new edition of the translation from 1932 with updated introduction).

- Guido Pfeifer : The laws of King Hammu-rapi of Babylon . In: Mathias Schmoeckel, Stefan Stolte (eds.): Examinatorium Rechtsgeschichte (= Academia Iuris - exam training ). Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-452-26309-4 , p. 1–4 (brief overview).

- Johannes Renger : Once again: What was the ammurapi 'code' - an enacted law or a legal code? In: Hans-Joachim Gehrke (Hrsg.): Legal codification and social norms in an intercultural comparison . Narr, Tübingen 1994, ISBN 3-8233-4556-7 , p. 27-59 .

- Gabriele Elsen-Novák, Mirko Novák: The "King of Justice" . On the iconology and teleology of the "Codex" Ḫammurapi. In: Baghdad communications . tape 37 , 2006, p. 131–155 ( uni-heidelberg.de ).

- Ursula Seidl: Babylonian and Assyrian flat art of the 2nd millennium BC Chr. In: Winfried Orthmann (Hrsg.): Der Alte Orient (= Propylaea art history ). tape 18 . Propylaeen Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, p. 300 f. (No. 181) .

- Herbert Petschow: On the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 146-172 .

- Herbert Sauren: Structure and arrangement of the Babylonian codices . In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History , Romance Department . tape 106 , 1989, pp. 1-55 .

- Irene Strenge: Codex Hammurapi and the legal status of women . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3479-1 .

- Victor Avigdor Hurowitz: Inu Anum ṣīrum . literary structures in the non-juridical sections of Codex Hammurabi. University Museum, Philadelphia 1994, ISBN 0-924171-31-6 .

- Dietz-Otto Edzard : The ancient Mesopotamian lexical lists - misunderstood works of art? In: Claus Wilcke (ed.): The spiritual understanding of the world in the ancient Orient. Language, religion, culture and society . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05518-5 , pp. 17-26 .

- Joachim Hengstl : The "Codex" Hammurapi and the exploration of Babylonian law and its significance for comparative legal history . In: Johannes Renger (ed.): Babylon: Focus on Mesopotamian history, cradle of early learning, myth of modernity. (= Colloquia of the German Orient Society ). tape 2 . SDV, Saarbrücken 1999, ISBN 3-930843-54-4 .

- Eckart Otto : Assault in the cuneiform rights and in the Old Testament . Studies on right-hand traffic in the ancient Orient (= AOAT . Volume 226 ). Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer 1991, ISBN 3-7887-1372-0 .

Web links

Translations

- Translation by LW King (1915) (PDF; 131 kB), English

- Ancient oriental texts on the Old Testament , Edition Alpha et Omega: German translation after Hugo Gressmann , Berlin 1926, p. 380ff.

Dubbing

- Attempts to reconstruct the spoken Akkadian . Including the spoken reading of the Codex Hammurapi with transcription. Website of the School of Oriental and African Studies , University of London

Background information

Individual evidence

- ↑ according to medium chronology

- ↑ Vincent Scheil: Code des lois de Hammurabi (Droit Privé), roi de Babylone, vers l'an 2000 av. J.-C. In: Mémoires de la Délégation en Perse, 2e série . tape 4 . Leroux, Paris 1902, p. 111-162 .

- ↑ cf. Viktor Korošec : Cuneiform right . In: Bertold Spuler (ed.): Orientalisches Recht (= Handbook of Oriental Studies ). 1. Dept. Supplementary Volume 3. Brill, Leiden 1964, p. 95 .

- ↑ Hugo Winckler: The laws of Hammurabi, King of Babylon, around 2250 BC. AD. The oldest law book of the world. JC Hinrichs, Leipzig 1902.

- ↑ cf. Cyril John Gadd : Ideas of divine rule in the Ancient East (= Schweich Lectures on Biblical Archeology . Volume 1945 ). British Academy, London 1948, pp. 90-91 .

- ↑ cf. Jean Nougayrol : Les Fragments du en pierre code hammourabien I . In: Journal asiatique . 1957, p. 339-366 . ; Jean Nougayrol: Les Fragments en pierre du code hammourabien II . In: Journal asiatique . 1958, p. 143-150 .

- ↑ a b cf. Arno Poebel : An old Babylonian copy of the Hammurabi law collection from Nippur . In: Oriental literary newspaper . 1915, p. 161-169 .

- ↑ a b cf. Gerhard Ries : prologue and epilogue in the laws of antiquity (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history . Volume 76 ). CH Beck, Munich 1983, p. 20 (habilitation thesis).

- ↑ cf. Gerhard Ries : prologue and epilogue in the laws of antiquity (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history . Volume 76 ). CH Beck, Munich 1983, p. 25 (habilitation thesis).

- ↑ cf. Gerhard Ries : prologue and epilogue in the laws of antiquity (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history . Volume 76 ). CH Beck, Munich 1983, p. 21 (habilitation thesis).

- ↑ literally: " Put in the mouth of the land"

- ^ Cruveilhier: Introduction au code d'Hammourabi . Leroux, Paris 1937, p. 4 .

- ↑ cf. Josef Kohler: Translation. Legal representation. Explanation . Pfeiffer, Leipzig 1904, p. 138 .

- ^ David G. Lyon: The Structure of the Hammurabi Code . In: Journal of the American Oriental Society . tape 25/2 , 1904, pp. 248-265 .

- ↑ for example by Mariano San Nicolò: Contributions to legal history in the field of cuneiform legal sources . Aschehoug, Oslo 1931, p. 72 .

- ^ Robert Henry Pfeiffer: The Influence of Hammurabi's Code outside of Babylonia . In: files of the 24th International Congress of Orientalists in Munich . 1959, p. 148 f .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 146-172 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 171 f .

- ^ A b Herbert Petschow: On the systematics and legal engineering in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 149 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 151 f .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 152 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 154 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 156 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 158 .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 160 f .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 162 f .

- ^ Herbert Petschow: To the systematics and legal technique in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 163 .

- ^ A b Herbert Petschow: On the systematics and legal engineering in the Codex Hammurabi . In: Journal of Assyriology . tape 57 , 1967, p. 166 .

- ↑ cf. Gerhard Ries : prologue and epilogue in the laws of antiquity (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history . Volume 76 ). CH Beck, Munich 1983, p. 27 (habilitation thesis).

- ↑ cf. E.g. Anton Moortgat : Babylon and Assur (= The Art of Ancient Mesopotamia . Volume 2 ). 2nd Edition. DuMont, Cologne 1990, p. 29 . or Fritz Rudolf Kraus : L'homme mésopotamien et son monde, à l'époque babylonienne ancienne (= Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afdeeling Letterkunde . NR, 36/6). North-Holland Publ., Amsterdam 1973, p. 138 .

- ↑ Gabriele Elsen-Novák, Mirko Novák: The "King of Justice": On the iconology and teleology of the 'Codex' Ḫammurapi . In: Baghdad communications . tape 37 , 2006, p. 131-155 .

- ↑ Gabriele Elsen-Novák, Mirko Novák: The "King of Justice": On the iconology and teleology of the 'Codex' Ḫammurapi . In: Baghdad communications . tape 37 , 2006, p. 136 f .

- ↑ cf. Erich Bosshard-Nepustil: On the representation of the ring in ancient oriental iconography . In: Ludwig Morenz, Erich Bosshard-Nepustil (ed.): Presentation of rulers and cultural contacts, Egypt - Levant - Mesopotamia (= Old Orient and Old Testament ). tape 304 . Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2003, p. 54 f .

- ↑ Gabriele Elsen-Novák, Mirko Novák: The "King of Justice": On the iconology and teleology of the 'Codex' Ḫammurapi . In: Baghdad communications . tape 37 , 2006, p. 149 .

- ↑ Johannes Renger : Once again: What was the ammurapi 'Code' - an enacted law or a legal book? In: Hans-Joachim Gehrke (Hrsg.): Legal codification and social norms in an intercultural comparison . Narr, Tübingen 1994, p. 27 .

- ↑ so also with Guido Pfeifer: The Laws of King Hammu-rapi of Babylon . In: Mathias Schmoeckel, Stefan Stolte (eds.): Examinatorium Rechtsgeschichte (= Academia Iuris - exam training ). Carl Heymanns, Cologne 2008, p. 1-4 .

- ^ A b Johannes Renger : Once again: What was the ‹ammurapi 'code' - an enacted law or a legal book? In: Hans-Joachim Gehrke (Hrsg.): Legal codification and social norms in an intercultural comparison . Narr, Tübingen 1994, p. 31 .

- ↑ cf. Wilhelm Eilers: The law stele Chammurabis . Laws at the turn of the third millennium BC. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1932. and Benno Landsberger: The Babylonian terms for law and law . In: Julius Friedrich (ed.): Symbolae ad iura orientis antiqui pertinentes Paulo Koschaker dedicatae (= Studia et documenta ). tape 2 . Brill, Leiden 1939, p. 219-234 .

- ^ Dietz-Otto Edzard : The ancient Mesopotamian lexical lists - misunderstood works of art? In: Claus Wilcke (ed.): The spiritual understanding of the world in the ancient Orient. Language, religion, culture and society . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, p. 19 .

- ^ Jean Bottéro : Le “Code” Hammu-rabi . In: Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa 12, 1 . 1988, p. 409-444 .