Cornelis de Bruyn

Cornelis de Bruyn , different spelling: Cornelis de Bruijn (* 1652 in The Hague , † around 1727 in Zydebaelen near Utrecht ) was a Dutch traveler, painter and author.

In the Netherlands

Little is known about the family background. His father was called Jan de Bruijn. Cornelis mentions three sisters in preparation for his second great journey; one of them, Anna Maria de Bruijn, is listed in the baptismal register of the Evangelical Lutheran Church (June 7, 1651). In the summer of 1674, Cornelis de Bruyn took courses at the Hague painters' guild, Pictura , led by Theodoor van der Schuer. He mastered Latin and French.

In his travel report he referred to himself several times as a partisan of William of Orange . The departure from The Hague coincides with an unsuccessful attack on the politician Johan de Witt , an opponent of Wilhelm, which was perpetrated by a young man from The Hague named Cornelis de Bruyn (June 21, 1672). The painter assured his readers that he had nothing to do with this namesake. It is still possible that Cornelis de Bruyn had reasons to avoid the Netherlands for a long time.

See also: Rampjaar .

First journey

On October 1, 1674, the 22-year-old painter set out on his first long journey, which initially took him to Rome, where he stayed for 18 months. He joined a group of Dutch artists, the Bentvueghels . When he was accepted into this group, he was "baptized" in the name of Adonis . When Pope Clement X died, de Bruyn was shown the favor of entering the chapel and touching the dead man's hand. During his travels, de Bruyn repeatedly found that doors opened for him - the reasons for this are not known.

Then he traveled on to the Levant. From 1678 to 1681 he lived in Izmir , with a longer stopover in Constantinople . The Islamic ban on images made it difficult for him to use the pencil openly, as he learned several times on his trip. When he arrived in Rhodes he wrote:

“As I was used to putting all the villages on paper when I got the chance, I had drawn them from two perspectives when I arrived, but as inconspicuously as I could. Because Rhodes is one of the strongest Turkish fortresses, I would have had to atone no less than my death if I had been discovered doing it. They imagine that the Christians have nothing else in mind with the drawings of their places than to use them against them on occasion. "

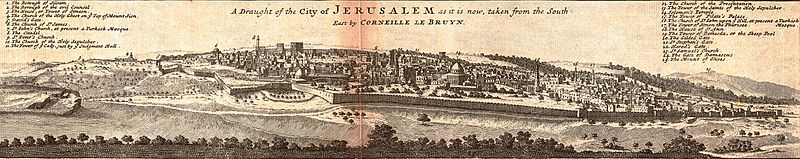

In 1681 he sailed to Egypt, where he visited Cairo , Saqqara and Alexandria . He then came to Palestine via Joppa and visited Jerusalem and Bethlehem .

For de Bruyn it was a matter of course that there was a market for oriental and especially biblical motifs and landscapes in the Netherlands. Even a Protestant, he let a Franciscan of the local custody and a dragoman accompany him on the sightseeing tour in Jerusalem , but constantly noted doubts about the Father's explanations. The pavement in Mary's tomb, for example, which was presented to him as antique, he considered fresh and new. On the other hand, he spent three days and nights inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, describing this as a deep religious experience.

His stay in Jerusalem was not without risk. Drawing holy places was strictly forbidden. The big city panorama that he made on the Mount of Olives was particularly difficult and took several days to complete. He set up a picnic area there with two monks and the dragoman so that they could hide the drawing utensils in the picnic basket if necessary.

De Bruyn traveled from Jerusalem to Tripoli . He spent the spring of 1682 exploring Accos and Galilee. He then lived in Aleppo for about a year . In the spring of 1683 he embarked for Cyprus, sailed to Antalya and from there returned by land to Izmir.

In October 1684 de Bruyn left the Ottoman Empire. He settled in Venice, where he lived eight years and drawing lessons with Johann Carl Loth took.

In March 1693, almost twenty years after his departure, Cornelis de Bruyn returned to The Hague, where his drawings, watercolors and paintings of oriental motifs were so popular that he decided to self-publish his travel impressions as his first book (1698 ) and dedicate to the bibliophile Prince of Wolfenbüttel Anton Ulrich zu Braunschweig and Lüneburg .

He enriched his own drawings with illustrations by other authors (especially Jean de Thévenot ). This work was a great success and was translated into French and English.

Second trip

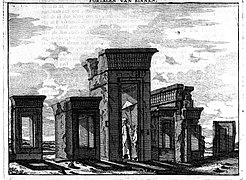

In the summer of 1701 Cornelis de Bruyn set out on his second long-distance journey. He reached Archangelsk by ship and from there to Moscow in the winter of 1701/02 by sledge . Letters of recommendation from the Mayor of Amsterdam gave him access to court, where he met Tsar Peter the Great several times and received orders for portraits. In April 1703 de Bruyn set out again. He sailed down the Volga , crossed the Caspian Sea, and arrived in Isfahan in November with a trade caravan on horseback . He lived there for a year; then he went on a three-month expedition to Persepolis to draw the antiquities there. Then he left Persia and reached Sri Lanka, Batavia (Jakarta), the Dutch West Indies via Bandar Abbas , whereupon he finally returned via the same stations as on the outward journey to The Hague.

He arrived here in October 1708 and immediately began to prepare the material he had collected on the trip for printing. This richly illustrated book was published in 1711; Translations into French and English followed.

Last years of life and death

De Bruyn's financial circumstances remain unclear. Undoubtedly, he could make money selling his art on the go. But there was no market for pictures in the Ottoman Empire. In addition, if more of de Bruyn's paintings had been sold on a large scale, they should have found their way into various collections; in fact, apart from the two books, only a few works by his hand are known. Perhaps he had a sponsor who made his long-distance trips possible. In any case, his situation deteriorated more and more in the 1720s, so that he died impoverished and lonely.

reception

De Bruyn's books were widely read in the 18th century. In many ways he gave Europe new information about foreign countries and cultures. Its lasting importance lies in the fact that the architectural studies, drawings and descriptions are very precise and thus differ positively from contemporary works.

Works

- Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn door de vermaardste deelen van Klein Asia, de eylanden Scio, Rhodus, Cyprus, Metelino, Stanchio, & c., Mitsgaders de voornaamste steden van Aeggypt, Syrien en Palestina. Verrijkt with the sea as 200 art posters by the author zelf na het leven afgeteekend . (1698)

- Reizen over Moskovie, door Persie en Indie verrijkt with 300 art posters by the author zelf na 't leven afgeteekend . (1711)

literature

- Jan Willem Drijvers: Bruijn, Cornelis de . In: Jennifer Speake (Ed.): Literature of Travel and Exploration, an Encyclopedia: A to F. Fitzroy Dearborn, New York / London 2003. ISBN 1-57958-247-8 , pp. 132-134.

- Jan Willem Drijvers, J. de Hond, H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg (eds.): "Ik hadde de nieusgierigheid". De reizen door het Nabije Oosten van Cornelis de Bruijn (ca.1652–1727) . Leiden / Leuven 1997.

- J. de Hond, Cornelis de Bruijn (1652-1726 / 27). A Dutch Painter in the East . In: GJ van Gelder, E. de Moor (eds.): Eastward Bound. Dutch Ventures and Adventures in the Middle East . London / Atlanta 1994, pp. 51-81.

- Judy A. Heyden: Cornelis de Bruyn: Painter, Traveler, Curiosity Collector - Spy? In: Judy A. Hayden, Nabil Matar (ed.): Through the Eyes of the Beholder: The Holy Land, 1517–1713 . Brill, Leiden 2013. ISBN 978-90-04-23417-8 . Pp. 141-164.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Een Hollandse signs ontmoet tsaar Peter de Grote. Inleiding. Retrieved July 21, 2018 .

- ^ Judy A. Hayden: Cornelis de Bruyn . S. 141.160 .

- ^ Judy A. Hayden: Cornelis de Bruyn . S. 153 .

- ↑ Cornelis de Bruyn en zijn reis. In: Digitale bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse letteren. Retrieved July 21, 2018 .

- ^ Judy A. Hayden: Cornelis de Bruyn . S. 151 .

- ^ Judy A. Hayden: Cornelis de Bruyn . S. 153 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bruyn, Cornelis de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bruijn, Cornelis de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch traveler, painter and author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1652 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | The hague |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1727 |

| Place of death | Zydebaelen near Utrecht |