Cosmographia (Sebastian Münster)

Cosmographia , later also called cosmography, named Sebastian Münster (1488–1552) , among others, his main work in the field of cosmography . It was the first scientific and at the same time generally understandable description of the knowledge of the world in German, in which the basics of history and geography, astronomy and natural sciences, regional and folklore were summarized according to the state of knowledge at that time. Cosmographia is the Latin form of the Greek kosmographía "description of the world" ( kósmos "world order", "universe"; gráphein "to write").

Under Kosmographie refers to the science of describing the earth and the universe; until the late Middle Ages geography, geology and astronomy were also part of this (see Cosmology of the Middle Ages ). Sebastian Münster is one of the famous cosmographers of the Renaissance , together with Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Martin Behaim (1459–1507), Martin Waldseemüller (1472 / 75–1520), Petrus Apianus (1495–1552) and Gerhard Mercator ( 1512-1594).

Emergence

After studying theology, ancient Greek, Hebrew, mathematics, geography, cosmography and astronomy, Sebastian Münster worked as a university lecturer in Heidelberg from 1521 to 1529. Already at this time (1524) the Alsatian humanist Beatus Rhenanus (1485–1547 ) suggested that Sebastian Münster should summarize his knowledge in the complete work of a cosmography. But it was not until he was at university in Basel (from 1529) and after he had been freed of everyday worries through his marriage to Anna Selber, the widow of the Basel book printer Adam Petri , that he was able to devote himself intensively to this great project and to his enthusiasm for geography . In a preparation period of around twenty years, his Cosmographia was created , on which, according to his own account, more than 120 "notables, scholars and artists" had worked.

In the introduction to one of his books, Münster writes modestly but confidently: "I expect neither wages nor honor for my work, rather the awareness that I have grown with the pounds that God has given me is sufficient ."

Title and content

The Latin title is Cosmographia or Cosmographiae universalis lib [ri] VI […] . The German-language work contains “a description of the whole world with everything in it” in six books. The first editions from 1544 to 1548 bear the Latin title Cosmographia , the editions from 1550 to 1614 the German title Cosmographei or description of all countries, ruled, fornemous stetten, histories, customs, handling etc. […]. or Cosmographey . The editions from 1615 to 1628 are again titled Cosmographia .

The full title of the first edition of 1544 reads:

- Cosmographia.

- Description of all countries by Sebastianum Munsterum, in which all peoples, rulers, Stetten and famous spots come from: manners, customs, order, belief, sects and handling, through the whole world, and especially the German nation. Whatever is found special in any one country and is found in it. Everything is explained with figures and beautiful tables, and made for eyes.

From the first edition onwards, Sebastian Münster added a dedication letter to the Swedish King Gustav I. Ericson Wasa to the Cosmographia , dated “Basel on August 17, 1544”, without it being possible to determine his motives.

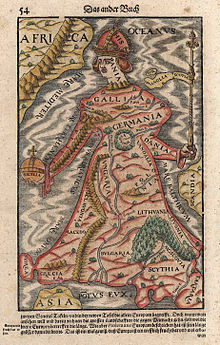

In the first book the basics of physical and mathematical-astronomical geography are presented. The following books contain country descriptions: Southern and Western Europe (2nd book), Germany (3rd book), Northern and Eastern Europe (4th book), Asia and the New Islands (5th book), Africa (6th book). Book).

swell

Sebastian Münster drew his knowledge from travel reports and stories from various scholars, geographers, cartographers and sea travelers. He also used literary works that were more or less believable. Marco Polo was also one of his sources, such as the report by the (fictional) knight Jehan de Mandeville on India and China, which was published in Liège in 1356. Thus Münster gradually described a fabulous world in which the strangest creatures occur, such as people with dog heads, large feet, blemmyes , double-headed as well as legendary animals and sea monsters. Most of these creatures are depicted on woodblock prints .

Collecting and researching other cities, countries and customs was not harmless. The theologian Sigismondo Arquer, for example, complained about the intolerance and greed of the church in his travel description of Sardinia, which he had made available to Münster for the Cosmographia . After his writing was translated into Italian, he had to justify himself to the Inquisition and was burned at the stake . The Latin edition of 1550 was censored by Hugo von Amerongen on behalf of the Inquisition. In all copies of the printed edition from 1550 available to the Inquisition, the censored areas were painted over with ink or pasted over with paper.

Münster had to sort out the stories he received according to their credibility and critically consider what he wanted to be considered a description of the world. In this way, for example, the report on the size of the pyramids in Egypt also suffers; in Münster's depiction they are described considerably smaller. The reports from the continents and countries known at the time are accompanied by numerous maps drawn by Münsters himself. The map of the world, which Münster had already drawn for Cosmographia in 1532 , only vaguely hinted at the new American continent 40 years after its discovery, and ten years after Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the world , it is far from reality.

At the end of the Cosmographia , Münster asks the reader not to reject the entire work because of errors or dissenting opinions, but rather to consider that it is impossible to please everyone.

However, his chapter on mines shows that he did not work exclusively in the office and second hand. It shows that he visited the Rumpapump silver mine in Alsace "in Hornung 1545" to study mining .

distribution

1544, the first issue of Cosmographia printed in the Offizin of Heinrich Petri in Basel. Heinrich Petri was a son from the first marriage of Münster's wife to the Basel printer Adam Petri .

The first edition of Cosmographia was in German in 1544 and over half of all editions up to 1628 were also in German. However, the work has also been published in Latin, French, Czech and Italian. The English editions only comprised part of the entire work. In 1898 Viktor Hantzsch identified a total of 46 editions (German 27; Latin 8; French 3; Italian 3; Czech 1) that appeared from 1544 to 1650, while Karl Heinz Burmeister only got 36 (German 21; Latin 5; French 6; Italian 3; Czech 1) that appeared between 1544 and 1628. The first edition of 1544 was followed by the second edition in 1545, the third edition in 1546, the fourth edition in 1548 and the fifth edition in 1550, each supplemented by new reports and details, text images, city views and maps and revised altogether. Little is known about who - besides the book printers Heinrich Petri and Sebastian Henricpetri - took care of the new editions after Münster's death. The 1628 edition was edited and expanded by the Basel theologian Wolfgang Meyer .

While the first edition of 1544 was only 660 pages long, the last edition revised personally by Münster in 1550 already contained 900 pages and the last ever printed edition of 1628 almost 1800 pages. In this way, around 50,000 copies in German and around 10,000 copies in Latin were produced in the Petri family's office in Basel in 84 years.

The costs for a bound work amounted to 2 guilders for the 5th edition, of which about 0.4 guilders went to the booksellers.

meaning

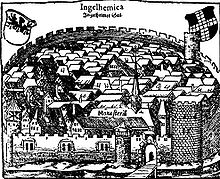

With Cosmographia, Sebastian Münster has published for the first time a joint work by learned historians and artists, by publishers, wood cutters and engravers. The numerous vedutas are usually made as woodcuts . Research was able to show that many of the images were not produced specifically for Cosmographia, but were taken from the print shop's inventory to enhance the quality of the work. So was z. B. the printing block of a hill fort is inserted several times and depending on the edition differently in several castles for illustration, as it were a pictogram for hill castle . Images describing the indigenous people of Africa and Asia have also been used identically a second time in different volumes.

With the editions of Cosmographia , a new quantitative and qualitative benchmark has been set for the equipment of city books. The Cosmographia was followed by other important city books as early as the 16th century. The multi-volume city book Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg , published between 1572 and 1617 , is based on the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by Abraham Ortelius in terms of format and layout, but its concept is based on Cosmographia .

Master draftsman and engraver

The most famous artists of the cityscapes, who could be determined by their monograms , include:

- Hans Rudolf Manuel Deutsch (1525–1571), the son of Niklaus Manuel , with the monogram HRMD, RMD or RM in ligature;

- Jakob Clauser or Klauser (1520–1578) with the monogram IC or IK, also in ligature;

- David Kandel (around 1538–1587) with the monogram DK, also found in ligature;

- Monogrammist HSD believed to be from Worms.

The most famous shape cutters who contributed to the Cosmographia are:

- Christoph Stimmer (or Christoff Schwytzer?), Form cutter in Strasbourg since 1550, with the mark -CS-;

- Heinrich Holzmüller , around 1550 goldsmith and form cutter in Bern and Basel, with the sign HH or HHF;

- Hieronymus Wyssenbach Basiliensis , form cutter in Basel, with the sign HWB;

- Martin Hoffmann , shape cutter in Strasbourg, with the mark MH or MHF;

- Master HIW who cut the Strasbourg woodcut;

- Master MG , who u. a. made the woodcut by Amberg;

- Gregorius Sickinger (around 1558–1631), painter, draftsman, form cutter, eraser and copper engraver from Solothurn, with the symbol GS; He is said to have worked as a form cutter in the editions of Cosmographia from 1578 onwards .

See also

literature

- Viktor Hantzsch : Sebastian Münster. Life, work, scientific meaning (= treatises of the philological-historical class of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences. 18, 3, ZDB -ID 219472-7 = treatises of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences. 41, 3). Teubner, Leipzig 1898 (Reprographic reprint. De Graaf, Nieuwkoop 1965), full text .

- S. Vögelin: Sebastian Munster's Cosmographey. In: Basler Jahrbuch 1882. Basel 1882, pp. 110–152 Internet Archive

- Karl Heinz Burmeister : Sebastian Münster. A bibliography. Pressler, Wiesbaden 1964.

- Peter H. Meurer : The new set of cards from 1588 in the cosmography of Sebastian Munster. In: Cartographica Helvetica. 4, Issue 7, 1993, ISSN 1015-8480 , pp. 11-20, full text .

- Frank Hieronymus: 1488 Petri Schwabe 1988 . Schwabe, Basel 1997, ISBN 3-7965-1000-0 , Volume 1, pp. 558-774.

- Hans Georg Wehrens: Freiburg in the "Cosmographia" by Sebastian Münster. In: Hans Georg Wehrens: Freiburg im Breisgau. Woodcuts and copperplate engravings. 1504-1803. Herder, Freiburg (Breisgau) et al. 2004, ISBN 3-451-20633-1 , p. 34 ff.

- Günther Wessel : From someone who stayed at home to discover the world. The Cosmographia of Sebastian Münster or How one imagined the world 500 years ago. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2004, ISBN 3-593-37198-7 .

Web links

- Overview of the issues of Cosmographia

- Collection of links to digitized versions of Cosmographia in various languages

- Digitized version of the German edition 1545

For more see

and in the Latin, Italian and French wikisource (links from the German site)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The numerous censored passages are in Thomas Theodor Crusius: Thomae Crenii Animadversiones Philologicae Et Historicae. Pars VIII, pp. 93–128 documents digitized material from the Munich digitization center

- ↑ s. Vogelin p. 122

- ↑ Viktor Hantzsch : Sebastian Münster. Life, work, scientific importance . In: Treatises of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences . 41st volume. BG Teubner, Leipzig 1898; Separate print, pp. 153–156 Digitized version of the Saxon State Library - Dresden State and University Library

- ↑ Karl Heinz Burmeister : Sebastian Münster - attempt of a biographical overall picture . Basel Contributions to History, Volume 91, Basel and Stuttgart 1963, pp. XV-XVI

- ↑ Cf. for example Sebastian Munster, Cosmographey or a description of all countries ruling and fornemesten Stetten of the whole earth [...]. New edition. S. Henricpetri, Basel 1588; Reprint Munich 1977.

- ↑ s. Vögelin p. 124 and Hantzsch p. 67, as well as Matthias Graf: Message from the living conditions of Doctor Wolfgang Meyers. In: Wolfgang Meyer, Johann Jakob Breitinger, Matthias Graf (editor): Additions to the knowledge of the history of the Synod of Dordrecht. JGNeukirch, Basel, 1825, p. 196 Google Books

- ↑ Wessel, p. 291

- ↑ so there is e.g. B. in the edition of 1550 for the castle Rötteln and the castle Hohenkrähen the same illustration

- ^ Hanswernfried Muth: Pictorial and cartographic representations of the city. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 294–307 and 901, here: pp. 294–298 ( Würzburg in the city books of 16th and 17th centuries ).