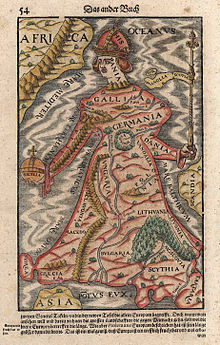

Europa Regina

Europa regina, Latin for Queen Europe , is a map-related, west-facing representation of the European continent with the motif of the queen. The cartographic motif was first used during the Mannerist era and was at times popular among cartographers.

origin

In the European Middle Ages , cosmographic maps were based on Jerusalem and faced east. Europe, Asia and Africa were arranged on the cycle maps in the so-called TO scheme. Maps centered on Europe remained very rare; the only known specimens are a map dated 1112 from the Liber Floridus by Lambert de Saint-Omer and a Byzantine map from the 14th century.

Only the Tyrolean cartographer Johannes Putsch (Latinized Johannes Bucius Aenicola ) produced a map of Europe again in 1537. This represented the Europa regina for the first time , albeit not so named. The European regions formed the figure of a woman with a crown , scepter and orb . This map was printed by the Calvinist Christian Wechel and enjoyed greater popularity during the second half of the 16th century. Although details of how it was created are uncertain, it is known that Putsch had close contacts with Emperor Ferdinand I , who came from the House of Habsburg , and that contemporaries referred to the image as Europa in forma virginis , translated as "Europe in the form of a virgin".

In 1587 Jan Bußemaker published an engraving by Matthias Quad , which showed an adaptation of the coup figure under the name Europae descriptio . Another version was presented consistently in the editions of Sebastian Munster's Cosmographia from 1588 , while earlier editions only showed the form of representation occasionally. Even Heinrich Büntings Itenerarium sacrae scripturae had a map of Europe in female figure in the issuance of the 1,582th This form was called "Europa regina" from around 1587.

description

The European regina has the shape of a young, pretty woman. The crown Portugal , shaped like the Carolingian temple crown , is placed on the head (Spain). France and the Holy Roman Empire form the upper body, adorned by the Alps and the Rhine as neck hangings. The heart lies in the original in Bohemia . According to another interpretation, the heart of Virgo Europe lies in Germany. In a contemporary description of Bünting's portrait of Europe, the Kingdom of Bohemia is "like a Güldener Pfenning or like a round gauntlet from Kleinodt" and "my heartfelt fatherland / the principality of Brunschwig " is the real heart.

The long robe includes Hungary , Poland , Lithuania , Livonia , Bulgaria , Moscow , Albania and Greece ; the Danube symbolizes belts or body chains as jewelry. The arms are Italy (the Kingdom of Naples and Rome ) and Denmark formed in her hands she carries left the scepter and right the orb ( Kingdom of Sicily ). Most of the illustrations show Africa, Asia and Scandinavia only partially, the British Isles only schematically.

symbolism

When the representation of the Europa regina was first published, Emperor Charles V ruled , who had united the possessions of the House of Habsburg in his hand, including his native Spain. The west-facing map with Spain as its head underscored the Habsburgs' universal claim to rule, especially over Europe. The imperial crown crown and imperial orb are obvious allusions to the imperial dignity of the Holy Roman Empire. The queen's robe corresponds to contemporary fashion at the court of the Habsburgs, and her face is said to have resemblances to Charles's wife, Isabella . As in the marriage paintings of the time, Europe looks to the right; which was interpreted to mean that she turned her face to her husband, the emperor, who was not depicted, and offered him power in the form of the imperial orb.

The map was also understood as a cognitive aid so that even geographically uneducated people could imagine Europe.

In general, Europe represents the united Christianity ( res publica christiana ) in the medieval tradition and as a ruling power in the world. Another interpretation is that of an allegory of paradise, based on the placement of the water: contemporary iconography depicted paradise as a closed form, surrounded by sea and rivers. The Danube in particular is represented with a four-armed delta mouth like the biblical river through paradise.

Related cards

In an earlier map by Opicino de Canistris from 1340, continents were already represented as people; in that case with Europe as a man and North Africa as a woman.

Allegorical forms were often used by other cartographers of humanism, so Bünting depicted Asia as Pegasus . The Leo Belgicus was a popular motif among Dutch map makers.

A more modern map from 1709, Europe. Volgens de nieuwste Verdeeling by Hendrik Kloekhoff, published by François Bohn, also shows Europe in the form of a woman with Spain as her head; but she looks south and stirs a pot, hunched over and hunched over, while Great Britain blows like a scarf in the wind. This “latest division”, to which the author alluded, was the reorganization of Europe during the coalition wars .

Individual evidence

- ^ Achim Landwehr: Introduction to European Cultural History , Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, ISBN 3-8252-2562-3 . Page 279.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Elke Anna Werner: Triumphante Europa - Klagende Europa. On the visual construction of European self-images in the early modern period. Page 243 ff. In: Roland Alexander Ißler; Almut-Barbara Renger (Ed.): Europe - bull and wreath of stars. From the union with Zeus to the union of states. Bonn University Press, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009, ISBN 3-89971-566-7 , pages 241-260.

- ↑ a b c d Anke Bennholdt-Thomsen: Zur Hermetik des Spätwerk, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1999, ISBN 3-8260-1629-7 , pages 22-24.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Michael Borgolte: Perspectives on European medieval history on the threshold of the 21st century. S. 16. In: Ralf Lusiardi, Michael Borgolte (ed.): The European Middle Ages in the arc of tension of comparison , Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-05-003663-X , pages 13-28.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Stephan Wendehorst: Reading book old Reich, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-57909-6 . Page 63

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Wolfgang Schmale: Europe, bride of the princes. Political relevance of the European myth in the 17th century. P. 244. In: Klaus Bussmann; Elke Anna Werner (Ed.): Europe in the 17th century. A political myth and its images . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08274-3 .

- ^ A b Marion Picker, Véronique Maleval, Florent Gabaude: The future of cartography: New and not so new epistemological crises . transcript Verlag, 2014. ISBN 3839417953 . Digitized , page 146 ff.