The tree of knowledge

The tree of knowledge (Spanish: El árbol del conocimiento ) is the title of a study published in 1984 by the Chilean biologists, neuroscientists and philosophers Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela on the development of life, in which they based their biological theory of cognition on the concept of autopoiesis imagine.

content

The tree of knowledge

Francisco Varela, together with his teacher and colleague Humberto Maturana, traces the biological history of life since the creation of the world and accentuates it anew. This is also expressed through corresponding conceptual formations: Thus the aspect of the struggle for life takes a back seat in the selection. This burdened term is replaced, in its place comes the natural drifting of living beings. The authors focus on processes of interaction with the milieu, as an environment with its own structural dynamics, in which, in their opinion, the principles of life and its development are expressed. In this context they also redefine the term determinacy : the structure of the living being determines how it is changed ( perturbed ). In their opinion, there is no improvement in optimization - for example through an improvement in adaptability and the use of the environment - but rather continuous phylogenetic selection with permanent structural linkages.

"Every doing is knowing, and every knowing is doing."

Community ethics

Maturana / Varela postulate their ethics based on the development history - first of the species (phylogenesis) and secondly of the individual living beings ( ontogenesis ) - and the social structures that emerged in this process : The origin is the act of love when people mate - as the basis for the socialization - and the dependence on the group members in order to survive as an individual and to ensure the offspring and their continued existence. That means: the community always has priority. M / V see in this the obligation of people to accept others and to work with them in order to be able to exist in their common world. To this end, they recommend the middle ground between different perspectively justifiable views. Finding this requires reflection and recognition (including our non-knowledge of the knowledge), which includes the entire body, and as recognition - in the awareness of the biological and social structure of the human being - is effective action .

Perspective of the observer

A second aspect of these representations is the conscious emphasis on the perspective of the observer , a living being [s] in the language . With emphasis on the cognitive, referential ( recursive ) process in understanding reality , Maturana / Varela speak here of ontieren , as the subject-bound conception of an image of reality. In doing so, they incorporate philosophy and cognitive sciences into their interpretation : Everything said is said by someone (second core aphorism .) The authors invite the reader to eat from their tree of knowledge - with the appeal: “The knowledge of knowledge” obliges to "constant vigilance against the temptation of certainty". With which the world we see "is not the world, but a world that we create with others".

Natural drifting

The development of life happens according to M / V without a draft , without directional planning (no steering force is necessary), solely through testing ( natural drifting ) of diverse alternatives (each individual case is the result of random variations :) The framework of life is history of the star, which begins with molecular homogeneity , followed by a continuous complex process of chemical transformations with a variety of molecular substances (e.g. carbon chains ) that enable the existence of living things and lead to the most complex shapes made up of harmoniously connected parts. In the history of development ( phylogenesis and evolution ), phenomena similar to the basic principle of reproduction through cell division occur again and again : every beginning of a life cycle can be traced back to a cell. Another example is the preservation of autopoiesis and the adaptation of living beings, in accordance with the drifting of the milieu.

Autopoiesis

M / V associate the term all living things with the autopoietic (= self-creating) organization , which they show using the example of a cell and transfer it to multicellular organisms . The goal of evolution is the continuation of the species with the help of the individual. The prerequisites for this are both an autonomous organization and an adaptation ( structural coupling ) to the environment, but not as a one-sided implementation of the demands of the outside world: In all of these processes there is not one actor and the target group , but mutually overlapping processes: Already in the Reproduction is not only involved in the DNS , but a whole network of interactions with e.g. B. the mitochondria and membranes in their entirety. This interplay for self-preservation consists of give and take, whereby the selected and adopted substances must fit the system and are processed by it. That means: The organs involved are connected to one another in a continuous network of interactions. The example of the cell makes this clear: the cell metabolism creates components that are integrated into the network of transformations that brought them about, and forms an edge (membrane) that constitutes the cell as a unit and itself participates in this transformation process through surgery is: by regulating the flow of substances from outside or inside. This means that it is only with substances (such as sodium - and calcium - ion interacts that match the organization of the cell and its structure). The resulting changes in the cell are therefore determined by its own structure as a cellular unit. This leads to an autonomy of the cell: It lives according to its own laws, but is not self-sufficient, i.e. dependent on essential supplies, just like the suppliers, who are organized according to the same principles. Consequently, in the survival process there must be a balance, a cooperation ( symbiosis ).

Second order autopoietic systems

The autopoietic organization can also be found in meta-cells like humans. Characteristic of Metazeller ( autopoietic systems of the second order with the formation of colonies and companies) is the development of the nervous system as an integral part of an organism. This enables the structural recursive coupling with the milieu: The milieu does not determine the unity, but only triggers structural changes in the autopoietic units. These react in a targeted manner - e.g. B. through selection and integrative processing - and thereby affect the milieu in turn: structural changes are therefore reciprocal and recursive .

Interneuronal network and cognition

A further stage of knowledge is the development of the nervous system into an interneuronal network - connecting motor and sensory cells - with the brain as the center. This occurs in connection with mobility (food, flight, reproduction) and the sensorimotor coordination required for this . M / V see this as the prerequisite for thinking, awareness and knowledge.

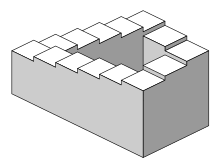

Two “worldview” interpretations

Maturana and Varela juxtapose two different interpretations of the worldview : The solipsistic perspective illustrated by Ernst Mach on the right is an individual construction . Likewise, the meaning of conceptualized terms depends solely on the states of consciousness of the thinking subject. The model contrary to this constructivist point of view is representationism , according to which the nervous system maps ( represents ), stores and processes the objects and relationships of the outside world (i.e. by obtaining information ) in brain modules by reacting to them by changing behavior. According to this theory, the milieu determines behavior in a targeted manner. M / V assess both viewing angles as two extreme locations that should be merged. This makes it clear why they do not want to be classified as constructivists : Although the first perspective draws attention to the limited capacity for knowledge, it can lead to a speculative head philosophy that is separated from the everyday world and thus to absolute cognitive loneliness. The second perspective implies a monocausal, linear explanatory model with simple cause / consequence or stimulus / reaction derivations (e.g. environment → living beings). M / V, on the other hand, see the biological and social processes as in many ways networked feedback : the nervous system as part of the organism acts in a structure- determined manner (in autopoietic surgery ), its behavior generation is therefore only triggered by the milieu, but not determined.

Third order coupling

The multitude of interlinked cycles shows an operational cohesion , which is essential for the maintenance of the organization as a whole - in the endeavor to keep the subsystems in balance. In the course of this process, differentiated social systems developed in the social vertebrates as a coupling of the third order in connection with the expansion of linguistic means of communication , which in turn promoted self-confidence and reflections as well as cultural behavior. According to M / V, language does not arise in a uniform design (is not part of the brain), but through the coordination of actions in a social context (is part of the milieu ), which is called the realm of language : our common “in-language” - Being [-] is what we experience as consciousness or as 'our spirit' and 'our I' ”. In this way M / V draws the bow to the appeal to the reader to implement the ethics defined above in the sense of the first core aphorism :

" Every doing is knowing, and every knowing is doing. "

classification

The theory of Maturanas and Varelas presented in The Tree of Knowledge is assigned to constructivism , which has three roots:

- and “[t] he third root is the work on the biological theory of cognition and the functioning of living systems by the […] biologists and neurocyberneticists […] Maturana and […] Varela. Initially developed independently, they were further developed in contact with [...] authors [from various academic areas and theoretical traditions] and are now attracting increasing interest in a variety of subject areas ”.

Her scientific method was also noticed and had an impact on other research disciplines . “The specificity of [their] contributions does not lie in an alleged better representation of" reality ", but in the method used to create them. Humberto R. Maturana describes it as follows: “As scientists, we make scientific statements. These statements are validated by the process we use to generate them: the scientific method. This method can be represented by the following operations:

a) observation of a phenomenon that is considered to be a problem to be explained;

b) developing a hypothesis in the form of a deterministic system capable of producing a phenomenon which is isomorphic with the observed phenomenon ;

c) Generation of a state or process which is to be observed as a predicted phenomenon according to the hypothesis presented;

d) Observation of the phenomenon thus predicted ”.

If one understands "observation" [of the predicted phenomena] as a constructive process in accordance with Maturana, one receives a description of science as a special form of problem-solving. The viability (in the sense of E. von Glasersfeld) of the problem solutions generated with this method is not determined by an undetectable correspondence with "the" reality. It depends on whether it allows us to act and whether we determine a (for) perceived correspondence with (individually or socially) established criteria for "good" solutions; H. decide that there is such a match ".

- Starting from these roots, one finds similarities to the spectrum of communication science to psychotherapeutic aspects of Paul Watzlawick .

- "The effects of the theory of autopoietic systems Maturanas and Varelas can also be seen in very differently oriented sociological studies", for example with Niklas Luhmann .

- “The development of empirical literary studies in Germany is closely connected with constructivism, which provided its philosophical foundation”.

- “What new aspect the theory of autopoietic systems opens up for art theory is revealed in a highly regarded article by N. Luhmann”.

Peter Hejl and Siegfried Schmidt have compiled a selection from the extensive literature of the 1980s and 90s, when the systems were constituted, and commented on them.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Maturana, Humberto and Francisco Varela: The tree of knowledge. The biological roots of human knowledge. German translation by Kurt Ludewig. Frankfurt a. M. 2009, p. 263 f. ISBN 3-596-17855-X and ISBN 978-3-442-11460-3 . This edition is quoted.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 5, p. 111.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 105.

- ↑ a b Maturana, Varela, p. 127.

- ↑ Humberto Maturana and Francisco J. Varela: The tree of knowledge. The biological roots of human knowledge. Bern, Munich, Vienna: Scherz-Verlag, 1987, p. 31.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, p. 264, Kp. 10: The tree of knowledge.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 259.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 267 ff.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 262 ff.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 1: Recognize the knowledge.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 13.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, p. 14: Neurofilosofia.

- ↑ a b Maturana, Varela, p. 32.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 263 ff.

- ↑ a b Maturana, Varela, p. 129.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 2: The organization of the living.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 51.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 115.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, pp. 65 ff.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 3: History: Reproduction and inheritance.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 91.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 113.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 35.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 78.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, pp. 85 ff.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 58.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, pp. 55 ff.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 99.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 4: The life of the "Metazeller"

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 96 ff.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 6: Areas of behavior

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 85.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, pp. 173 ff.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 7: Nervous system and knowledge

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, pp. 154 ff.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 180.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 205.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 8: The social phenomena

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Natural History of Human Language : 229 ff.

- ↑ Maturana, Varela, Kp. 9 Linguistic areas and human consciousness

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 226.

- ^ Maturana, Varela, p. 251.

- ^ Foerster, Heinz von, Glasersfeld, Ernst von, Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J., Watzlawick, Paul: Introduction to Constructivism: Contributions by Heinz von Foerster, Ernst von Glasersfeld, Peter M. Hejl, Siegfried J. Schmidt, Paul Watzlawick . Piper, Munich 1992. ISBN 978-3-492-21165-9

- ↑ a b Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Bibliography . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 167.

- ^ Foerster, Heinz von: Discovering or inventing. How can understanding be understood? In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , pp. 41–88. (Including an examination of the postulates of constructivism and inclusion)

- ↑ Glasersfeld, Ernst von: Construction of Reality and the Concept of Objectivity . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , pp. 9–40. (With an overview of the philosophical tradition)

- ↑ a b Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Bibliography . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 169.

- ↑ Benseler, Frank, Hejl, Peter M., Köck K. (Eds.): Autopoiesis, Communication, and Society, The Theory of Autopoietic Systems in the Social Sciences . Frankfurt / M., New York: Campus, 1980.

- ^ Roth, Gerhard, Schwegler, Helmut (Eds.): Self-organizing Systems, An interdisciplinary approach . Frankfurt / M., New York: Campus, 1981.

- ↑ An der Heiden, Uwe, Roth, Gerhard, Schwegler, Helmut: The organization of organisms: self-production and self-preservation . Funct. Biol. Med. 1985, pp. 330-346.

- ↑ Riegas, Volker, Vetter, Christian (ed.): On the biology of cognition. A conversation with Humberto R. Maturana and contributions to the discussion of his work . Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1990.

- ↑ Maturana, Humberto R .: Recognize: Biology of language: the epistemology of reality. In: The Organization and Embodiment of Reality, Selected Works on Biological Epistemology, authoris. German barrel v. WK Köck, Braunschweig, Wiesbaden: Vieweg (philosophy of science and philosophy, vol. 19) 1982, p. 236 f.

- ↑ Hejl, Peter M: Construction of the social construction. Basics of a constructivist social theory . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 111 ff.

- ↑ Watzlawick, Paul: Adjustment to Reality or Adapted »Reality«? Constructivism and Psychotherapy . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 89 ff.

- ↑ a b Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Bibliography . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 172.

- ↑ Luhmann, Niklas: Autopoiesis, actions and communicative understanding . In: magazine f. Sociology 11, 1982, pp. 366-379.

- ↑ Hejl, Peter M .: Construction of the social construction. Basics of a constructivist social theory . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , pp. 109–146. (With detailed references)

- ^ Schmidt, Siegfried J .: From the text to the literary system. Sketch of a constructivist (empirical) literary study . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , pp. 147–166.

- ↑ Finke, Peter: Constructive Functionalism. The epistemological basis of an empirical theory of literature . (= Concept Empirical Literary Studies, Vol. II) Braunschweig, Wiesbaden: Vieweg 1982

- ↑ Rusch, Gerhard: Understanding understanding. An attempt from a constructivist point of view . In: Luhmann, N., Schorr, KE (Ed.): Between intransparency and understanding. Questions to pedagogy . Frankfurt a. M .: Suhrkamp 1986, pp. 40-71.

- ↑ Rusch, Gerhard: Autopoiesis, literature, science - what literary studies can learn from cognitive theory. In: Siegener Studies 35, WS 1983/84, pp. 20-44.

- ^ Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Art and science from a constructivist point of view . In: Sauerbier, SD (Ed.): On the changed relationship between art and science today (Art and Therapy Vol. 5). Münster: Ref. 1984, pp. 166-176.

- ↑ Schmidt, Siegfried J. (Ed.) The discourse of radical constructivism . Frankfurt a. M. 1987.

- ↑ Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Bibliography . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , p. 173.

- ↑ Luhmann, N: The work of art and the self-reproduction of art . Delfin III, August 1984, pp. 51-69.

- ↑ Hejl, Peter M., Schmidt, Siegfried J .: Bibliography . In: Foerster u. a .: Introduction to Constructivism , pp. 167–180.