The eight

The Eight ( Hungarian : Nyolcak ) (1909–1918) was the most important Hungarian avant-garde group of artists at the beginning of the 20th century. The avant-garde tendencies, especially Fauvism and Post-Impressionism , the painting of Paul Cézanne and, to a lesser extent, Expressionism , Cubism and Secession, had an impact on the art of eight . The eight was a revolutionary group of artists. Its members were seekers of new forms of expression for the new epoch.

Members

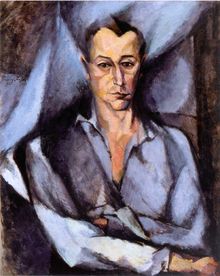

Members of the artist group were Róbert Berény , Dezső Czigány , Béla Czóbel , Károly Kernstok , Ödön Márffy , Dezső Orbán , Bertalan Pór and Lajos Tihanyi. Two sculptors joined the group as guests: Vilmos Fémes Beck and Márk Vedres as well as the writer and artist Anna Lesznai . György Bölöni followed her activities with interest and wrote about her.

history

Prehistory in Paris

The members all came to Paris to study in the first years of the 20th century and participated in academic education for a shorter or longer period. The most popular institute in the district was the Académie Julian : between 1901 and 1907, Bertalan Pór, Ödön Márffy, Béla Czóbel, Dezső Czigány, Róbert Berény, Dezső Orbán and Károly Kernstok - except the latter - all studied here as painting students of Jean-Paul Laurens . From time to time they also attended the evening courses of the other private schools, such as the classes of the Académie Colarossi , Grand Chaumiére and Humbert, where the prominent representatives of the French Fauves Henri Matisse , André Derain and Albert Marquet also appeared at the time. Márffy enrolled at the national École des Beaux-Arts , where he attended Fernand Cormon's class for four years . It was from here that such innovative world greats as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , Vincent van Gogh , Henri Matisse and later Francis Picabia and Chaim Soutine came from .

Between 1905 and 1909, Czóbel, Márffy, Berény and Czigány exhibited their paintings more or less regularly at the Salon d'Autumne and the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. This brought them closer and closer to Fauvism, and Czóbel and Berény had even exhibited together with the French Fauves.

Prehistory in Hungary

Czóbel was the only one of the eight who actively participated in the work of the artists' colony in Nagybánya , although Tihanyi, Czigány and Orbán also came there. Béla Czóbel exhibited his most recent paintings, brought home from Paris, in Nagybánya in the summer of 1906. Many of them were deeply impressed by the new style of the Fauves. Czóbel undoubtedly played a key role in the style development of the Hungarian "savages". He not only influenced the “Neos”, that is, who sought their style under modern French influence, but also Károly Kernstok , who was older than Czóbel and was considered a mature painter; in 1907 he invited Czóbel to his estate in Nyergesújfalu . The later leading figure of the artist group, the eight, steered the joint work there from naturalism in the direction of renewing tendencies. The next summer, Ödön Márffy, who had started to constructively process the experience of his four-year training, went to see Kernstok on his estate. The joint work decisively further developed the artistic approach of both, and their Fauvist painting developed here in Nyergesújfalu. From 1906 Kernstok and his friends, who were open to modern aesthetics, founded a true intellectual workshop. Dezső Czigány, Béla Czóbel, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pór and János Vaszary stayed here among the painters; The guests also included the sculptor Márk Vedres, the artisan and writer Anna Lesznai, the poet Endre Ady , the philosopher Georg Lukács , the art historian Károly Lyka , the art collector Marcell Nemes and the journalist Pál Relle. So there were those creative intellectuals in Nyerges who were to be decisive in the creation of the group “The Eight”.

The later members of the eight - with the exception of Berény - initially took part in the exhibitions of the MIÉNK (Magyar Impesszionisták és Naturalisták Köre - Circle of Hungarian Impressionists and Naturalists). This first modern art association in Hungary was founded in 1907, and Czóbel and Márffy were accepted into the group of predominantly conservative founding members because the influential Kernstok and József Rippl-Rónai , who had previously belonged to the Nabis artist group, were on their side Admission passed. MIÉNK was then gradually expanded to include the young artists of the "Hungarian Fauves", which, however, increased the tensions that existed within the group from the outset. During their second exhibition it became clear that the respective stylistic sensibilities were so divergent that the possibility of separation was considered. All of this did not escape the attention of the “opposing” side: “Meanwhile, evil tongues claim,” wrote the conservative art critic László Kézdi-Kovács, “that Kernstok are pursuing another secession, leaving Miénk and going under the name 'Keresők' (The Seekers ) together with the local ultra-youth, those young giants of our art, will found a new artist group. "

New pictures - The debut of the eight

The Kézdi-Kovács prophecy came true ten months later, on December 19, 1909. On that day the press reported that eight painters - Róbert Berény, Dezső Czigány, Béla Czóbel, Károly Kernstok, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pór and Lajos Tihanyi - a group exhibition entitled Új Képek (New Pictures) in the Salon Kálmán Könyves Könyves Kálmán Szalon organized. Most of the members of the artist group that formed around Kernstok came from the youth of the Hungarian Fauves, but they were not recruited from the rural artists' colony in Nagybánya - so it is significant that none of the prominent representatives of the Neos was involved in the exhibition project. At that time the group of artists did not give themselves a name, only the exhibition was given a title. The designation »New Pictures« was a clear reference to the example of epochal importance taken from literature: the volume of poetry Új Versek (New Poems) by Endre Ady , which was published in 1906. In doing so, the painters wanted to suggest that they represented the same intellectual Parisian mentality with their artistic means as the poet with his verses. The critics immediately took up the literary reference and repeatedly spoke of the »painterly adysm« in connection with the exhibition.

The 32 pictures in the exhibition caused a major scandal. In Hungary at that time, even impressionistic, naturalistic painting was not yet established, the unnatural-looking, garish colors, the non-idealized, even disfiguring representation of the naked human body outraged the general public. The media response, however, attracted crowds of visitors to the exhibition; New newspaper articles were published daily that criticized the new painting or, conversely, defended it. Theoretical discussions about the modern directions of the visual arts were held. On January 9, 1910, Kernstok presented his essay "The Inquiring Art" to the Galileo Circle, to which the philosopher Georg Lukács answered a week later with his essay "The paths have separated". Both texts were published in the most effective cultural journal of the time, the Nyugat (West).

The second exhibition of the eight

The artists only officially adopted the name Die Acht ( Nyolcak ) for their second exhibition, which took place in April 1911 in the prestigious National Salon Nemzeti Szalon . Not only the choice of location and the elegant catalog indicated that they were now approaching the matter much more seriously than when they made their debut, but also the professional press campaign, which was primarily led by Pál Relle and György Bölöni. With the intellectual elite of the time at their side, the exhibition was expanded into a real cultural festival with a whole series of events. The accompanying program focused in particular on three areas: art criticism, literature and contemporary music. Of course, an exhibition of this kind that was willing to renew itself was accompanied by numerous debates and symposia, but the artist group The Eight was able to reach a wider audience than is usually the case with exhibitions by including new Hungarian literature and contemporary music. An evening of discussion, one lecture followed another, and in the mornings you could attend literary matinees. From the perspective of music history, it was a major event when the Waldbauer-Kerpely Quartet Bartók and Weiner's string quartets, Jenő Kerpely Kodály's cello sonata and Béla Bartók performed his own piano pieces at the Nemzeti Szalon. In general, it can be observed that the fauvistic brushwork of the eight, which appeared absent-minded, was increasingly being replaced by a more disciplined image structure. Their once "wild" colors also became more reserved, the contrasts more subdued. In her drawings of groups of nudes, the need for classification appears. As they used to graduate with the academies, they now began to strive for an aesthetic of lasting value. The main reason behind the change was the rediscovery of Paul Cézanne, who died in 1906 . This change in style bears a great resemblance to that which also took place among the French "savages" during these years. With Georges Braque all this leads to the elaboration of analytical cubism, but the corresponding cubist characteristics also appear in the paintings of the Fauve artists Derain, Dufy, Vlaminck and Friesz. Confronted with the new direction, some members of the Eight and the Neos felt addressed, but they did not delve further into the spatial problems of analytical cubism.

The eight - apart from Kernstok and Pór - created their still lifes and landscape paintings, influenced by Cézanne's painting, in rapid succession in the early 1910s , and their popular nude compositions and Arcadian scenes are also mainly due to Cézanne's pictures of bathers, although these pictures are not their only ones Were inspiration. Under the sign of the "iron laws of art" the Hungarian painters resorted to the Etruscan sculptures, the Greek vase paintings, the Italian Renaissance or the compositions of Hans von Marées and Ferdinand Hodler , which manifested itself primarily on their monumental canvases and murals.

The Mayor of Budapest at the time, István Bárczy , made it a priority that the new public buildings should be decorated with the work of contemporary masters. This concern helped some of the eight to get profitable jobs. From a remark by Dezső Orbán, however, it can be concluded that the opportunities that suddenly opened up led to tensions within the group: “We only stuck together for a few years,” Orbán remembers. “Jealousy and envy, especially envy, led to the breakup. “In fact, only four - Kernstok, Pór, Márffy and Czigány - were able to participate in the money-making murals, while Orbán, Berény and Tihanyi were given no such opportunities. Czóbel was not interested in the matter because he lived in Paris all the time. In 1912, group cohesion weakened, although this was consistently denied by the members of the eight in the press.

The third exhibition of the eight, the dissolution of the group

The third exhibition of the eight took place six months later, on November 15, 1912, in the National Salon. Only four - Berény, Orbán, Pór and Tihanyi - attended, but the catalog had all eight names as evidence that the group still existed. After the third, they did not hold any further group exhibitions, but they presented their works at larger collective exhibitions; so they were treated together by the press for a long time. Her paintings could be seen in the exhibitions of the Kunsthaus, founded in 1913. The Kunsthaus used to be seen as a competition for the eight. In the so-called exhibition of the palace inauguration, opened in January 1913, only Márffy took part in addition to Kernstok, but during the National Post-Impressionist Exhibition in April seven again exhibited her works, with drawings by Béla Czóbel. (The title of the exhibition was deceptive, because from the catalog it turns out that mainly French Fauvists and Cubists and the members of the Brücke and The Blue Rider with the Hungarian Modernists.) A year later, during the great Kunsthaus exhibition in 1914 almost all of them again, only Bertalan Pór was missing. In December 1913, the five major American cities touching traveling exhibition began in New York, the official title of which was "Exhibition of Contemporary Graphic Art in Hungary, Bohemia, and Austria". Among the forty Hungarian artists, works by all members of the eight were on display. During the Hungarian performance that stopped at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in 1914, the works of Tihanyi and Berény were left out. However, the jury raised no objections to the works of Kernstok, Czigánys, Orbán, Márffy and Pórs. Bertalan Pór declared solidarity with his two comrades; so they exhibited in a not so well known room, in the art salon Brüko. The others stayed in the artist house. This incidence , which led to the weakening of the group's internal solidarity, ended the story of the eight. They took part in one final exhibition together, the San Francisco World's Fair , the art department of which was called the prestigious Panama-Pacific International Exposition . The eight were given a separate hall, which was particularly imprecisely referred to as Hungarian Cubists in a magazine.

With the outbreak of World War I , the French-inspired, but autonomous and invenziose phase of Hungarian painting ended. Czóbel, who worked in Paris, fled to the Netherlands, most of the members of the Eight continued to work as war painters. The group never officially dissolved, but was not reorganized after the war. The artist group "KÚT" (New Society of Fine Artists), founded in 1924 after a long break, recognized the legacy of the eight for their own.

Memorial exhibitions

- 1961. Budapest, Hungarian National Gallery. (Graphic Department): The Eight and the Activists

- 1965. Székesfehérvár, István Csók Gallery: The Eight and the Circle of Activists

- 1981. Budapest, Hungarian National Gallery: The Eight and the Activists

- 2005. Debrecen (Debrezin), Ferenc Medgyessy Memorial Museum: The Eight and the Activists

- 2010. Pécs (Fünfkirchen), Museum Janus Pannonius: The Eight - Under the magic of Cézanne and Matisse

- 2011. Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts: The Eight

- 2012. Vienna, Art Forum: The Eight. Hungary's Highway to Modernity

- 2012. Vienna, Collegium Hungaricum: The Eight - The Act.

- 2013. Paris, Musée d'Orsay: Allegro Barbaro. Béla Bartók et la modernité hongroise (1905-1920).

literature

- Krisztina Passuth : A Nyolcak festészete. Budapest 1967, 2011, ISBN 978-963-329-032-3 .

- Krisztina Passuth: Meeting places of the avant-garde East Central Europe 1907 - 1930 . From the Hungarian: Anikó Harmath. Budapest: Balassi 2003 (Hungarian 1998)

- Mariann Gergely: Budapest: 1906-1911. In: Suzanne Pagé (sous la direction de): Le Fauvisme ou l'épreuve du feu. Éditions des musées de la Ville de Paris, 1999, ISBN 2-87900-463-2 , pp. 326-335.

- Sophie Barthélemy, Joséphine Matamoros, Dominique Szymusiak, Krisztina Passuth: Fauves hongrois (1904–1914). Ed. Adam Biro, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-35119-047-0 .

- Gergely Barki, Zoltán Rockenbauer: Dialogue de Fauves / Dialogue onder Fauves / Dialog among Fauves. Hungarian Fauvism (1904-1914). Silvana editorale, Bruxelles / Milano 2010, ISBN 978-88-366-1872-9 . (German English French)

- Csilla Markója, István Bardoly (eds.): The Eight. Janus Pannonius Múzeum, Pécs 2010, ISBN 978-963-9873-24-7 .

- Gergely Barki , Evelyn Benesch , Zoltán Rockenbauer : The eight. A Nyolcak. Hungary's Highway to Modernity. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-422-07157-5 , p. 208.

- Gergely Barki, Zoltán Rockenbauer: The Eight - The Act. Exhibition catalog. Balassi Institute, Budapest 2012, ISBN 978-963-89583-4-1 , p. 112.

- Barki Gergely, Claire Bernardi, rock builder Zoltán: Allegro Barbaro. Béla Bartók et la modernité hongroise. 1905-1920. Edition Hazan - Musée d'Orsay, 2013, ISBN 978-2-7541-0712-9 .

Web links

- Pécs, Museum Janus Pannonius: The Eight, 2010. ( Memento from January 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 5.0 MB)

- Vienna, Art Forum: The Eight. Hungary's Highway to Modernity, 2012.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gergely Barki, Zoltan Rockenbauer: From the Fauvist Beginnings to the »New Pictures«, 1905–1910. In: The eight. A Nyolcak. Hungary's Highway to Modernity. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Vienna 2012, pp. 26–37.

- ^ Zoltán Rockenbauer: The Fauves by the Danube, or Could Nyergesújfalu Have been Hungary's Collioure ? In: Krisztina Passuth, György Szücs (Ed.): Hungarian Fauves from Paris to Nagybánya. Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest 2006, pp. 125-132.

- ↑ (Kézdi.) [Kézdi-Kovács László]: A MIÉNK Új kiállítása. In: Pesti Hírlap. February 14, 1909, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Új Képek kiállítása. In: Független Magyarország. December 19, 1909, p. 14.

- ↑ Bányász László: Képkiállítások. Ország-Világ, 1910, p. 59 .; K. F [Kanizsai Ferenc]: Neo-impresszionisták tárlata. In: Magyar Hírlap. December 31, 1909, p. 14.

- ↑ Kernstok Károly: A kutató művészet. In: Nyugat. 3. 1910. I, pp. 95-99; Lukács György: Az utak elváltak. In: Nyugat. 3. 1910. I, pp. 190-193.

- ^ Zoltán Rockenbauer: New Pictures, New Poems, New Music. Allies of the Eight, from Ady to Bartók. In: Markója Csilla, Bardoly István (ed.): The Eight. Janus Pannonius Múzeum, Pécs 2010, pp. 70–89.

- ^ Letter from Dezső Orbán. Sydney, March 11, 1959. Quoted in: Béla Szíj: La vie de Róbert Berény, de son enfance à son émigration à Berlin. In: Bulletin de la Galerie Nationale Hongroise. 4. Budapest 1963, p. 19.

- ^ Barki Gergely: The Panama-Pacific International Exposition: Hungarian Art's American Debut or Its Bermuda Triangle? In: Centropa. 10, 2010, 3, pp. 259-271.