The thing with B.

The thing with B. is a story by the German writer Hans Joachim Schädlich . It was published in 1992 and was awarded the Johannes Bobrowski Medal in the same year . In a detached narrative Harmful describes his relationship with his older brother Karl Heinz Harmful which the younger brother for years as unofficial collaborator for the Ministry of State Security of the GDR had collected information on what until after the turn at Schädlich insight into the Stasi became apparent .

content

The narrator reports on his relationship with his four years older brother, whom he just calls "B.", not "B.", because this sounds too much like a police protocol. He worries that he will not be able to tell the story completely and that it will be worthwhile at all. Again and again he interrupts the report with questions about the narration, for example whether time specifications are necessary or the chronological order should be observed. At the same time, his story remains too firmly stuck in reality.

The narrator grows up in the shadow of his older brother, who is preferred to him by his parents and who is always four years ahead of the younger. Still, the narrator is proud of his brother. The older one teaches the younger one a lot, not without making sure to maintain his lead at all times. The order of the brothers is preserved until the narrator presents the first literary work, whereupon locals and non-residents start to be interested in him.

The difference between “locals” and “non-residents” is explained: both are separated by a border that the locals cannot cross. Seen from both sides, the narrator and the other locals are “behind the border”. Writers from across the border visit the narrator. Under the suspicion of the "secret state police", meetings take place in the country, which the older brother also attends. He has to justify himself as a member of the ruling party for the meetings and is ultimately expelled from the party. Relieved, he reports to the younger brother that from now on nothing will stand in the way of his visits. When the narrator's first book appears on the other side of the border, he is threatened with prison in his home country, but is finally allowed to leave. He can only maintain personal contact with his older brother at occasional meetings in third countries.

After the border has fallen, the narrator returns home for the first time. He learns from records that his older brother reported regularly to the state police about him, including from private meetings after his departure. When he confronts the brother, the earlier roles are reversed. Now the elder asks the younger for advice, as he is not the only one he has reported on. At the request of the younger one, he calls the other victims and confesses his actions to them. With this the narrator concludes his report. Once again he emphasizes that he can only partially report the story and that it has no end.

Background and history

Hans Joachim Schädlich's brother Karlheinz Schädlich was an unofficial employee of the GDR Ministry for State Security under the code name “IM Schäfer” . In this function he reported on his circle of friends who were critical of the regime and also on his brother Hans Joachim, against whom the MfS had been running an operational case under the name “Pest” since 1976 . When Hans Joachim introduced his brother to other writers like Günter Grass , Karlheinz also gathered information about this. Even after his brother moved to the Federal Republic in 1977, Karlheinz Schädlich reported to the State Security about the joint meetings in Budapest, Prague and West Berlin. In 1979 he received from the hand of Erich Mielke , the Distinguished Service Medal of the National People's Army in bronze. His cooperation with the State Security did not end until December 1989, one month after the fall of the Berlin Wall , because of “no prospects”.

Shortly after the Gauck authority was established, Hans Joachim Schädlich, together with Jürgen Fuchs , Katja Havemann , Ulrike and Gerd Poppe and other GDR civil rights activists, inspected his Stasi files in early 1992 . In response to when Schädlich found his brother's notes on himself, he described: “I went out and drove home. I was stunned then. Simply stunned. I have seldom noticed such a disbelief in myself as it was at this hour. ”After confronting his brother about the find, he admitted his espionage activities. According to Schädlich, his brother was equally disturbed that his deeds suddenly came to light, as that he had committed them. The state security had put pressure on his brother that he could not withstand. Instead of accepting the possible disadvantages of a refusal, he betrayed his brother, to which Schädlich judged: "Nobody was forced to do that."

In the same year that the files were inspected, Schadenlich wrote the story The Case with B. The published version was preceded by a version that, according to Schädlich, "was also burdened with my emotions". Finally, he decided to keep his emotions as a participant completely out of the narrative, and thus again approached the style of his first attempted proximity . Schadlich explained: "A description of something should not describe the descriptor's feelings, but rather, through the description, arouse the feelings of readers."

With the story, Hans Joachim Schädlich closed the topic for himself: “What I had to say about it, I said in my text The Case with B. , and what my brother has to say about it, he said by saying nothing Has. Done. For me. "The contact between the two brothers broke off, but starting from the end of the story, Schädlich declared:" The story doesn't have an end either. - The end is open as long as we live. ”On December 16, 2007, his brother Karlheinz Schädlich shot himself, which the authorities classified as a suicide . In 2009, Susanne Schädlich , a daughter of Hans Joachim Schädlich, published her autobiographical memory Immer wieder December. The West, the Stasi, the uncle and me , in which she revisits her own biography, the story of her family and her uncle.

style

The thing with B. is told in laconic , sparse language, the style distant and compressed. According to Franz Huberth, the reserved nature of the first-person narrator shows the distance to his own past, as expressed in him by a distant experience in the GDR and a distance from its state institutions. Through the childhood story, described in childish naivety, the reader is offered an identification and at the same time a dramaturgical fall is built up for later betrayal.

The deliberately general and indeterminate time and place indications attempt to raise the story to the level of a fable . But the narrator complains that a complete solution from his own autobiography is not possible; Several times he reveals his helplessness in dealing with the biographical facts. In the narrative flow, the chronological order is repeatedly broken or switched to the level of the narrator, his narrative theoretical problems with completeness, time indications and his own observer role are revealed. With these distancing measures, Schadlich prevents, according to Huberth, "that a linear sequence of happy childhood, cheated life and later disappointment turns into a trivial stirring piece ."

interpretation

Secret Service Methods

The first sentence of the story reads: “I can't tell the whole thing about B. because I wasn't there all the time.” This introduction already reflects the topic of secret service surveillance in several ways : The goal is always to ensure the information is complete . The person concerned, the target of the observation, remains excluded from the information. A life story is depersonalized into a "thing", the person anonymized by his abbreviation. "B." could equally stand for a name, for "brother" or "observer". The narrator does not prefix the neutral abbreviation with an article in order to distance himself from the language in the files. After the betrayal, however, a familiar form of address no longer seems possible.

Again and again the text plays with allusions to information and its concealment. With increasing knowledge, the re-evaluations of the experiences increase. Friendliness, assistance and meetings lose their innocence from an afterthought and add up to evidence of the spying. In the reported trivialities, as in the simple, casually reporting style, the exaggerated hysteria of the supervisors is exposed.

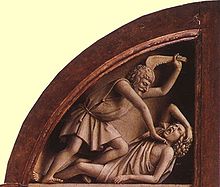

Biblical allusions

Huberth saw the story as a "story of Cain and Abel ", whereby the biblical model is complicated in reality: the motive of the deed remains in the dark, the act of killing extends over decades, in the end Cain does not face God as judge, but his victim Abel. The biblical template can also be generalized to the whole society of the GDR transferred by the State Security the fratricide to the opposition "brothers" through decomposition measures verübe.

The tone of the story also refers to the Bible several times. It changes for the first time when the narrator discovers literature: "It happened at that time" - a tone that is immediately dismissed as "ridiculous". But the phrase also evokes echoes of the first book of Moses and the biblical account of Cain and Abel as well as the Christmas story , the birth of Jesus Christ , whose social work was also perceived by the rulers as a subversion . The linguistic style of the New Testament can also be extracted from the last section : “I believe that. I've seen it. [...] What should I do now? "," Go to the others and tell them: 'Yes, it is true'. "The catharsis of the conversation is banned into a religious ritual, which, however, cannot be sustained for long. In the end, the narrator confesses his perplexity: "I don't know."

Reality and unreality

Two almost identical sections, between which historically the turning point and the inspection of files lie, end with almost identical formulations: “My text is just so stuck to real reality. I would prefer it to be different. ”And:“ My text sticks a lot to the real unreality. I would prefer it otherwise. ”The sentences have very different meanings in the respective context. In the first section, the author is caught up in the narrative problem that his text, which he wants to keep free of any historicity, repeatedly requires a specific reference to time. However, through inspection of the files, the “real reality” of the narrator's biography becomes a “real unreality”, a reality that the person concerned does not want to admit and wants to reinterpret in fiction.

In the end, as a reaction to the disappointed trust, there is a flight into empiricism : only what is seen is believed; the story remains incomplete until all the details are known. Ultimately, Huberth saw the narrator prevented by his own writing inhibition from telling his story in full. It also has no end, since the brothers remain indissolubly connected for life.

reception

For The thing as the Harmful was in 1992 by the jury Berliner Literature Prize with the Johannes Bobrowski Medal awarded. The story became the most translated work by Schädlich. According to Yaak Karsunke , “Schadenlich was the first to succeed in writing a literary text on the Stasi complex.” Maike Albath called the story “[k] a triumphant accounting, but an unadorned protocol, precise and sparse. It is oppressive evidence of betrayal. ”Franz Huberth also used the word“ oppressive ”. For him, through literary means, “Schadlich's text became autobiographical literature, which gains its density not through content, but through language, and thus goes far beyond the purely private.” Heinz Ludwig Arnold simply spoke of “an impressive text”. For Uwe Kolbe knew how harmful "quite cold to tell all dissecting with an unprecedented distance this story." He self-published in 2003 under the title The thing with V. a throwback to Schädlich story he on his own family history and Father transferred. Walter Hinck emphasized the “personal immediacy” in Schädlich's arrangement and drew the conclusion with regard to the subject of manipulation and surveillance, which had already shaped his novel Tallhover a few years earlier : “If ever an author has ever been caught up with his literary subject in reality , then it's Hans Joachim Schädlich. "

literature

Text output

- Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Kursbuch 109, 9/1992, pp. 81-89.

- Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Prussian Sea Action Foundation (ed.): The Berlin Literature Prize 1992 . Gatza, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-928262-12-2 , pp. 71-83.

- Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Wulf Segebrecht (Ed.): Information from and about Hans Joachim Schädlich . Literature footnotes. University of Bamberg , Bamberg 1995, ISSN 0723-2950 pp. 10-18.

- Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Verena Auffermann (Ed.): Best German storytellers 2000 . DVA, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-421-05386-3 , pp. 41-64.

Secondary literature

- Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Böhlau, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-03503-3 , pp. 252-257.

Web links

- How the writer settled accounts with his brother . Excerpts from the story The matter with B. In: Welt Online from December 9, 2006.

- Stasi as a topic in literature - The matter with V. Aspects of literary journalism after opening the files . Lecture by Uwe Kolbe as part of the Studium generale of the University of Tübingen on July 3, 2002.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Marian Blasberg: The Dandy of East Berlin . In: The time from December 31, 2008 ( pdf version with pictures ( memento of the original from September 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and remove then this note. ).

- ↑ a b c d Pun: Attempted closeness. The writer Hans Joachim Schädlich is seventy years old . Broadcast manuscript of Deutschlandradio Kultur from October 4, 2005 (rtf file).

- ↑ "Nobody was forced to do that." Interview with Hans Joachim Schädlich. In: Wulf Segebrecht (Ed.): Information from and about Hans Joachim Schädlich . Literature footnotes. University of Bamberg , Bamberg 1995, ISSN 0723-2950 pp. 28-32.

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller: Hans-Joachim Schädlich - Two studies and a conversation (PDF; 231 kB) . Issue 13 (February 1999) of the Institute for Cultural Studies in Germany at the University of Bremen , p. 43 (PDF file).

- ↑ In writing at home. How writers go about their work . Conversation with Herlinde Koelbl . In: Hans Joachim Schädlich: The other look. Essays, speeches, conversations . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, ISBN 3-499-23945-0 , p. 308.

- ^ Susanne Schädlich: Again and again December. The West, the Stasi, the uncle and me . Droemer, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-426-27463-7 . Review notes for December again and again at perlentaucher.de .

- ↑ See section: Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Pp. 253, 255, 257.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schädlich: The matter with B. In: Kursbuch 109, 9/1992, p. 81.

- ↑ See section: Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Pp. 253-255, 257.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schädlich: The matter with B. In: Kursbuch 109, 9/1992, p. 85.

- ^ A b c Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Kursbuch 109, 9/1992, p. 89.

- ↑ See section: Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Pp. 254, 256-257.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Schädlich: The thing with B. In: Kursbuch 109, 9/1992, p. 88.

- ↑ See section: Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Pp. 255-256.

- ↑ Prussian Sea Trade Foundation (ed.): The Berlin Literature Prize 1992 , p. 83.

- ^ Yaak Karsunke : Prohibition of naming. Hans Joachim Schädlich: “Attempted closeness” . In: Karl Deiritz, Hannes Krauss (eds.): Treason of art? Review of the GDR literature. Structure, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7466-8005-0 , p. 190.

- ↑ Franz Huberth: Enlightenment between the lines. The Stasi as a topic in literature . Pp. 257-258.

- ↑ Heinz Ludwig Arnold : The subversive chronicler. About Hans Joachim Schädlich . In: Ronald Speirs (Ed.): The Writers' Morality / Die Moral der Schriftsteller . Festschrift for Michael Butler. Peter Lang, Oxford 2000, ISBN 0-8204-5306-4 , p. 106.

- ↑ Uwe Kolbe : Stasi as a topic in literature - The matter with V. Aspects of literary journalism after opening the files. Lecture as part of the Studium generale at the University of Tübingen on July 3, 2002.

- ↑ Uwe Kolbe: The thing with V. In: Franz Huberth (Hrsg.): The Stasi in German literature . Attempto, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-89308-361-8 , pp. 151-155.

- ↑ Walter Hinck: With language fantasy against the trauma. Hans Joachim Schädlich. The writer and his work In: Wulf Segebrecht (Ed.): Information from and about Hans Joachim Schädlich , p. 40.