Domestication

Domestication (also domestication , from Latin domesticus "domestic") is an intraspecific process of change in wild animals or wild plants , in which these are genetically isolated from the wild form by humans over generations . Wild animals are domesticated to domestic animals , wild plants are to be cultivated . Because of this and further breeding , use by humans is often only possible or usability can be improved enormously (see farm animals and useful plants ).

The following text deals with the domestication of animals. For plants see plant breeding .

Domestication of animals

The first domestication of wild animals took place in the same regions, and by the same human populations, who also grew the first plants and developed crops from them, i.e. were the first to farm . The only exception, as far as is known, is the dog, which was domesticated by nomadic hunters and gatherers thousands of years before they settled down. For most of the early domestic animals, three independent centers of the earliest domestication can be identified, which at the same time were independent regions when agriculture was invented: the " Fertile Crescent " in the Middle East about 10,500 to 10,000 years ago, at the same time, or a little later, Central China, and, much later, the South American Andes. As soon as people in other regions also began to settle down and do agriculture, or the first farmers from the early centers immigrated to new regions, further suitable species were domesticated in the new regions. Genetic studies (including palaeogenetic studies based on bone fragments excavated in archaeological excavations) show that the domestic animals were in genetic exchange with wild populations of the original species in the same region for thousands of years after their domestication. Modern animal breeding, which keeps pets under complete control and tries to avoid any contact with wild animals, is a comparatively young invention and only became common thousands of years after the first domestication.

The domestication of wild animals should not be with the taming be mistaken for a single wild animal. Domestication has only been successful for a few species, while others, although some of them have been tamed and kept for thousands of years, could never be domesticated. Although the people of the first farming cultures hunted gazelles on a large scale ( Edmigazelle and Dorkasgazelle ) and sometimes kept them in large fences for a long time, they were never domesticated. Also onager (wild ass) or zebras were, despite many attempts and closely related species of domestic animals, not domestizierbar.

By the onset of domestication of an animal species, the conditions for the development of the species are changed decisively. The natural evolutionary development is replaced by conscious or unconscious selection criteria of humans. The genetic characteristics of the animals therefore change in the context of domestication.

If people engaged in agriculture immigrated to new regions, they usually took their pets with them instead of starting over with domestication in their new home. This means that the original home of many domestic animals can also be narrowed down to widespread wild parent species. However, matings with wild animals also occurred in the new region and this led to introgression of their genetic makeup. As in the case of European domestic pigs, the alleles of the animals originally brought from Anatolia in this case could be almost completely displaced from the gene pool and replaced by those from the new region, here European wild boar.

Although the domestication of each species was an independent event, scientists today group it together into three scenarios or "paths".

Domestication through commensalism

For some of the first domesticated species, a scenario is believed likely where the initiative came from wildlife rather than humans. According to this, wild animals specifically sought out humans and their settlements, for example to look for food in waste. Only later did people not only hunt these familiar animals, but gradually take them more and more into their care. The fact that one species benefits from another species in its diet without disadvantaging or damaging it is known in zoology as commensalism , which is why the hypothesis got its name. Domestication in this way is being discussed for dogs and house cats, but also house pigeons, for which human structures could initially serve as "artificial breeding rocks". Guinea pigs, chickens, or even wild boars could have joined humans as garbage eaters. The wet rice culture in China provided a habitat for carp, ducks and geese even before they became pets.

Domestication as prey

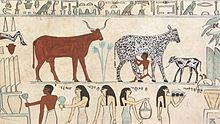

For the most important domestic animals of the early Neolithic farming cultures, sheep, goats and cattle, it is assumed that animals initially driven into enclosures by driven hunt were kept there as a kind of living store before they remained in human care and became pets. Such mass hunts of the respective cultures are archaeologically proven by finds, some of them kilometers long, barriers in today's Jordan and Syria. At the same time it can be seen that the animals became rarer due to the sharp hunting of the growing human population. An indication of longer keeping is when young animals and female animals predominate in the bone material, which are better suited for this than the more aggressive males. It does not seem improbable that long-term keeping was not initially intended, but resulted from the necessity of having to stretch out the increasingly rare prey for longer and longer periods of time.

Direct domestication

Direct domestication assumes that wild animals were deliberately captured and kept with the clear intention of using them in the long term and making them pets. While the other scenarios are assumed to have developed by chance, the will to domesticate would have been there from the start. This seems more plausible for most late domesticated species where the concept of domestic animals was already known and could now be carried over to new species. Direct domestication inevitably appears above all for species that were not primarily kept as meat suppliers but for other uses, such as horses, donkeys and camels originally kept as carrying and draft animals (and only much later as mounts).

Important domesticated species

Predators

Wolves as dogs were the first pets and were probably initially as a hunting helper and later as herding dogs dressed. Another theory is that the wolf (as a puppy) joined humans. This early stage of (self) domestication can still be observed today on Pemba in East Africa and Namibia. According to this theory, the “house dog” is a wolf that persists in the juvenile phase, which is supported by the observation that juvenile wolves can be trained in the same way as dogs; with puberty, however, they lose all tameness and change to pure wolf behavior (e.g. increased flight distance ).

Early evidence, a paw print in Chauvet Cave , is over 23,000 years old. A 1975 in a cave in the Siberian Altai Mountains found Canidenschädel applies to morphological criteria as a fossil of a dog that has been dated at 33,000 years. According to a genetic calculation, the dog and the wolf are said to have separated at least 135,000 years ago ( Stone Age ), which means that dogs or tamed wolf offspring have lived with humans as pets for a much longer time; More at: house dog .

House cats are a species of predator domesticated about 9,000 years ago that was first detected in Cyprus. In Central Europe they did not displace the previously domesticated ferret , which descends from the polecat , until some time after the beginning of our era .

Herbivores

Herbivores initially served as a meat supply; it was not used as a farm animal (draft animal) until thousands of years later. Humans began domesticated first animals as early as 13,000 years ago (11,000 BC), presumably in the area of the Fertile Crescent , first sheep , later cattle and goats . Such pets arrived on Cyprus 10,300 years ago. The pig was probably domesticated in Asia around 11,000 years ago.

The first draft animal was the castrated bull 7,500 years ago. Donkeys and horses (in the Kazakh steppe) came later as pack animals , then as draft animals and finally as mounts. At the same time, the dromedary was the first type of camel to be used. Original characteristics of the horse were preserved in the Caspian pony. However, studies on the mitochondrial DNA of the animals did not reveal any common breeding strain. After the Ice Age, the horse remained as a "residual population" in isolated areas (e.g. Iberian horses). A crossbreeding of such residual wild populations is assumed to explain this picture. This is a form of post-domestication that began in 3500 BC. In north-eastern Europe and from 1500 BC Ch. Can also be detected in Western Europe (Shetland pony).

In recent prehistory, llama and guinea pigs were domesticated on the American continent and reindeer in Russia for meat production . In the recent time, the domestication of various laboratory and pets such as falling hamsters and color mouse .

Presumed chronology and sources

The chronological classification of many domestication results has not yet been clearly clarified. Some domestications occurred several times (multicentric), therefore several times or several areas are often given:

| animal | Wild animal | years ago | place | swell |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dog ( Canis lupus familiaris ) |

wolf | 30000 | probably multicentric: Europe, Africa, Asia |

According to the traditional view in the last Ice Age, min. 14,000 years ago; most likely domesticated more than 30,000 years ago |

|

Sheep ( Ovis orientalis aries ) |

Mouflon | 11000 | Western Asia: Northwest Iran and Anatolia |

|

|

Pig ( Sus scrofa domestica ) |

wild boar | 11000 | multicentric: Middle East, China |

|

|

Goat ( Capra aegagrus hircus ) |

Wild goat (bezoar goat ) | 11000 | West Asia: Iran | |

|

Cattle ( Bos primigenius taurus ) |

Aurochs | 10,000 | middle East | |

|

Cat ( Felis silvestris catus ) |

Black cat | 9500 | Levante, Cyprus | |

|

Zebu ( Bos indicus ) |

Asiatic aurochs ( Bos primigenius namadicus ) | 8000 | Pakistan | |

|

Chicken ( Gallus gallus domesticus ) |

Bankiva chicken | 8000 | South East Asia | Insecure dating of soil layers with bones, domestication possibly thousands of years later and in several places |

|

Guinea pig ( Cavia porcellus ) |

Real guinea pigs | 7000 | Peru | |

|

Donkey ( Equus asinus asinus ) |

African donkey | 7000 | Northeast Africa | |

| Water buffalo ( Bubalus bubalis ) |

Water buffalo ( Bubalus arnee ) | 6300 | West india | Swamp buffalo presumably independent in southern China / northern Thailand about 3600 years ago |

|

Alpaca ( Vicugna pacos ) |

Vicuna | 6000 | Peru | . |

|

Horse ( Equus ferus caballus ) |

Wild horse | 5000-6000 | Kazakh / Ukrainian steppe | |

| Balirind |

Banteng ( Bos javanicus ) | 5500 | Indonesia | Zebu was crossed into most races (hybrid) |

|

Llama ( Lama glama ) |

Guanaco | 5000 | Northern Chile / Northwest Argentina | |

|

Goose ( Anser anser domesticus ) |

Greylag goose | 5000 | Egypt | Most Chinese breeds come from the Swan Goose Anser cygnoides from |

|

Silk moth ( Bombyx mori ) |

Bombyx mandarina | 5000 | China | . About 400 years ago, a second species of silk moth ( Chinese oak silk moth ) domesticated in China |

|

Ren animal ( Rangifer tarandus ) |

reindeer | 5000 | Russia | independent in Scandinavia by the Sami |

|

Trample ( Camelus bactrianus ) |

Wild camel | 5000 | Mongolia or Northern China | |

| Yak ( Bos grunniens ) | yak | 5000 | Tibet / Qinghai | . According to genome analyzes, 10,000 years are also possible |

|

Domestic pigeon ( Columba livia forma domestica ) |

Rock dove | 4500 | Middle East | . Possibly much earlier, but definitive evidence is missing. |

| Breeding carp including koi | carp | 4000 | China | . Europe possibly independent 2000 years ago. Koi around 1200 years old, China. |

|

Duck ( Anas platyrhynchos domesticus ) |

Mallard | 3000 | China | . In Europe: high / late Middle Ages, presumably independent |

|

Dromedary ( Camelus dromedarius ) |

Wild dromedary (extinct) | 3000 | South arabia | |

|

Ferret ( Mustela putorius furo ) |

Polecats | 2500 | Egypt | |

| Turkey or domestic turkey ( Meleagris gallopavo forma domestica ) |

Turkey ( Meleagris gallopavo ) |

2200 | Mexico | . Somewhat younger, second domestication center in the American Southwest |

|

Goldfish ( Carassius auratus auratus ) |

Gable / crucian carp | 1000 | China | |

|

Rabbit ( Oryctolagus cuniculus ) |

Wild rabbit | 500 | France |

Changes in characteristics through domestication

Domestication is usually associated with a number of typical changes in characteristics compared to the wild form. Even Hermann von Nathusius examined her example on Schweineschadel (1864). The domestication effects include both anatomical changes and changed behavior.

Outward appearance

- Training of breeds with sometimes serious differences in appearance (for example the dog breeds derived from the wolf ):

- Reduction of the fur (for example in domestic pigs):

- Color change from camouflage colors to more diverse, conspicuous color variants (for example goldfish or koi):

Wild carp

- Reduction of the teeth and horns

- Appearance of lop ears

- Steeper forehead

- Decrease in brain mass by up to 34 percent, decrease in furrowing , especially in the areas of the brain that are important for processing sensory impressions

- Reductions in the digestive tract

- Reinforcement of properties useful for humans (e.g. milk yield in cattle)

Behaviors

- Reduced aggressiveness

- Less well developed escape and defense behavior

- Increased rate of reproduction, sometimes up to the complete abandonment of seasonality of reproduction

- Less pronounced brood care behavior

Since such effects can sometimes also be observed in humans (e.g. in comparison to Neanderthals ), some biologists (including Konrad Lorenz ) also speak of the "depletion" of humans in the course of their development, others of "self-domestication". Many of these traits are retained youth traits. One speaks here of neoteny .

Transferred word meaning

The words domesticate and domestication can also be used transposed, e.g. B. “domesticate wild ideas”, comparable to words like tame or curb . In domestication , this transferred use is not common.

See also

- Dedomestication

- livestock farming

- Tameness

- Domestication in North Africa

- Domestication of the goldfish

literature

- Helmut Hemmer: Neumühle-Riswicker deer . First scheduled breeding of a new form of livestock. In: Klaus Rehfeld (Ed.): Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau . 58th year, no. 5 . Scientific publishing company, 2005, ISSN 0028-1050 , p. 255-261 . (Breeding of a farm animal form from fallow deer that shows all the characteristics of domestication in just a few generations. Behavioral characteristics were coupled with easily comprehensible fur characteristics.)

- Lyudmila N. Trut: Early Canid Domestication: The Farm-Fox Experiment . American Scientist 1999; 87, pp. 160-169. (Decades of attempts in Siberia to breed domestic animals from silver foxes with the trait “friendly to people”.) PDF

- Daniel Zohary, Maria Hopf: Domestication of Plants in the Old World. The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley . (Oxford Science Publications.) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Daniel Zohary: Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin 2000

Web links

- Desmond Morris: How the Wolf Got Into the House: Domestication of Dog and Cat. In: NZZ Folio . November 1997

- Michael Stang : Accelerated evolution: How domestication is changing the animal world on a lasting basis deutschlandfunk.de, April 12, 2009

- Co-Evolution of Humans and Dogs: An Alternative to Canine Domestication Theory. Translation by Schleidt / Shalter (2003): Co-evolution of humans and canids: An alternative view of dog domestication. In: Evolution and Cognition. Volume 9, No. 1, 2003, pp. 57-72

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Greger Larson & Dorian Q. Fuller (2014): The Evolution of Animal Domestication. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 45. pp. 115-136. doi: 10.1146 / annurev-ecolsys-110512-135813 .

- ↑ Zeder, Melinda A .: Pathways to Animal Domestication. Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability, 2012.

- ↑ for Cyprus: J.-D. Vigne, I. Carrére, F. Briois, J. Guilaine (2011): The early process of mammal domestication in the Near East. Current Anthropology 52: 255-271. doi: 10.1086 / 659306

- ↑ Der Spiegel: The Trail of the Companion

- ↑ Anna Druzhkova: Wissenschaft.de - an old dog

- ↑ C. Natanaelsson, MC Oskarsson, H. Angleby, J. Lundeberg, E. Kirkness, P. Savolainen: Dog Y chromosomal DNA sequence: identification, sequencing and SNP discovery. In: BMC genetics. Volume 7, 2006, p. 45, doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2156-7-45 , PMID 17026745 , PMC 1630699 (free full text).

- ↑ Where the house cats come from , Bild der Wissenschaft from June 29, 2007.

- ^ Juliet Clutton-Brock : Origins of the dog: domestication and early history. In: James Serpell (Ed.): The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press, 2009

- ↑ Germonpré, M., Sablin, MV, Stevens, RE, Hedges, REM, Hofreiter, M., Després, V. (2009): Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. Journal of Archaeological Science 36: 473-490

- ↑ Nikolai D. Ovodov, Susan J. Crockford, Yaroslav V. Kuzmin, Thomas FG Higham , Gregory WL Hodgins, Johannes van der Plicht (2011): A 33,000-Year-Old Incipient Dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the Earliest Domestication Disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum. PLoS ONE 6 (7): e22821. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0022821 (open access)

- ↑ Druzhkova AS, Thalmann O, Trifonov VA, Leonard JA, Vorobieva NV, et al. (2013) Ancient DNA Analysis Affirms the Canid from Altai as a Primitive Dog. PLoS ONE 8 (3): e57754. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0057754 .

- ↑ a b Melinda A. Zeder (2008): Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA vol. 105 no. 33: 11597-11604. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0801317105

- ↑ E Giuffra, JM Kijas, V. Amarger, O. Carl Borg, JT Jeon, L. Andersson: The origin of the domestic pig: independent domestication and Subsequent introgression . In: Genetics . 154, No. 4, April 2000, pp. 1785-1791. PMID 10747069 . PMC 1461048 (free full text).

- ↑ G. Larson, K. Dobney, U. Albarella, M. Fang, E. Matisso-Smith, J. Robins, S. Lowden, H. Finlayson, T. Brand, E. Willerslev, P. Rowley-Conwy, L. Andersson, A. Cooper: Worldwide phylogeography of wild boar reveals multiple centers of pig domestication . In: Science . 307, No. 5715, March 2005, pp. 1618-21. doi : 10.1126 / science.1106927 . PMID 15761152 .

- ↑ Ceiridwen J. Edwards et al .: Mitochondrial DNA analysis shows a Near Eastern Neolithic origin for domestic cattle and no indication of domestication of European aurochs Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2007; 274, 1377-1385. See Section 5: Conclusions .

- ^ Hazel Muir: Ancient remains could be oldest pet cat . In: New Scientist . April 8, 2004. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Marsha Walton: Ancient burial looks like human and pet cat . In: CNN . April 9, 2004. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Carlos A. Driscoll, Marilyn Menotti-Raymond, Alfred L. Roca, Karsten Hupe, Warren E. Johnson, Eli Geffen, Eric H. Harley, Miguel Delibes, Dominique Pontier, Andrew C. Kitchener, Nobuyuki Yamaguchi, Stephen J. O 'Brien, David W. Macdonald (2007): The Near Eastern Origin of Cat Domestication. Science 317: 519-523. doi: 10.1126 / science.1139518

- ↑ Shanyuan Chen, Bang-Zhong Lin, Mumtaz Baig, Bikash Mitra, Ricardo J. Lopes, António M. Santos, David A. Magee, Marisa Azevedo, Pedro Tarroso, Shinji Sasazaki, Stephane Ostrowski, Osman Mahgoub, Tapas K. Chaudhuri, Ya-ping Zhang, Vânia Costa, Luis J. Royo, Félix Goyache, Gordon Luikart, Nicole Boivin, Dorian Q. Fuller, Hideyuki Mannen, Daniel G. Bradley, Albano Beja-Pereira (2010): Zebu Cattle Are an Exclusive Legacy of the South Asia Neolithic. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27 (1): 1-6. doi: 10.1093 / molbev / msp213

- ^ West B, Zhou BX .: Did chickens go north? New evidence for domestication . (PDF) In: World's Poultry Science Journal . 45, No. 3, 1989, pp. 205-218. doi : 10.1079 / WPS19890012 .

- ↑ YW Miao, MS Peng, GS Wu, YN Ouyang, ZY Yang, N. Yu, JP Liang, G. Pianchou, A. Beja-Pereira, B. Mitra, MG Palanichamy, M. Baig, TK Chaudhuri, YY Shen, QP Kong, RW Murphy, YG Yao, YP Zhang: Chicken domestication: an updated perspective based on mitochondrial genomes. In: Heredity. Volume 110, Number 3, March 2013, pp. 277–282, doi: 10.1038 / hdy.2012.83 , PMID 23211792 , PMC 3668654 (free full text).

- ^ History of the Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus) in South America, a summary of the current state of knowledge

- ↑ Luise Dirscherl: The Pharaoh and his donkey - Ancient Egyptian finds provide information on the history of domestication. In: Informationsdienst Wissenschaft e. V. Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, Communication and Press Department, March 19, 2008, accessed on March 28, 2010 .

- ↑ A. Beja-Pereira, et al. : African origins of the domestic donkey . In: Science . 304, No. 5678, June 2004, p. 1781. doi : 10.1126 / science.1096008 . PMID 15205528 .

- ↑ oger Blench: The history and spread of donkeys in Africa (PDF; 235 kB)

- ↑ Satish Kumar, Muniyandi Nagarajan, Jasmeet S Sandhu, Niraj Kumar, Vandana Behl (2007): Phylogeography and domestication of Indian river buffalo. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7: 186 doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2148-7-186

- ↑ Y. Zhang, D. Vankan, Y. Zhang, JSF Barker (2011): Genetic differentiation of water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) populations in China, Nepal and south-east Asia: inferences on the region of domestication of the swamp buffalo. Animal Genetics 42: 366-377. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-2052.2010.02166.x

- ↑ a b Jane C. Wheeler (2012): South American camelids - past, present and future. Journal of Camelid Science 5: 1-24.

- ^ Hélène Martin and Dominique Armand: The horse: Domestication. In: Steppe Warriors. Riding nomads of the 7th – 14th centuries Century from Mongol. Primus Verlag, LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, 2012, p. 88 f. Excerpt: “The sites suggested as the cradle of horse keeping are in areas such as Ukraine and Kazakhstan and are between 5000 and 6000 years old. An example is the settlement of Botai in Kazakhstan, which dates back to about 3700-3100 BC. And in which the oldest evidence for the domestication of the horse was found. "

- ^ JA Lenstra & DG Bradley: Systematics and phylogeny of cattle. In R. Fries & A. Ruvinsky (eds.): The genetics of cattle. CABI, 1999. ISBN 0-85199-258-7

- ↑ Nijman IJ, Otsen M, Verkaar EL, de Ruijter C, Hanekamp E, Ochieng JW, Shamshad S, Rege JE, Hanotte O, Barwegen MW, Sulawati T, Lenstra JA. (2003): Hybridization of banteng (Bos javanicus) and zebu (Bos indicus) revealed by mitochondrial DNA, satellite DNA, AFLP and microsatellites. Heredity 90 (1): 10-16. doi: 10.1038 / sj.hdy.6800174

- ↑ Geese

- ↑ Wenqi Zhu, Kuanwei Chen, Huifang Li, Weitao Song, Wenjuan Xu, Jingting Shu, Wei Han (2010): Two Maternal Origins of the Chinese Domestic Gray Goose. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances Volume: 9, Issue: 21: 2674-2678. doi: 10.3923 / javaa.2010.2674.2678

- ^ Marian R. Goldsmith, Toru Shimada, Hiroaki Abe (2005): The genetics and genomics of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Annual Review of Entomology Vol. 50: 71-100. doi: 10.1146 / annurev.ento.50.071803.130456

- ↑ Yanqun Liu, Yuping Li, Xisheng Li, Li Qin The origin and dispersal of the domesticated Chinese oak silkworm, Antheraea pernyi, in China: A reconstruction based on ancient texts. Journal of Insect Science 10: 180. online

- ^ Bryan Gordon (2001): Rangifer and man: An ancient relationship. Rangifer Special Issue No. 14 (The Ninth North American Caribou Workshop): 15-28.

- ↑ Knut H. Røed, Øystein Flagstad, Mauri Nieminen, Øystein Holand, Mark J. Dwyer, Nils Røv, Carles Vila (2008): Genetic analyzes reveal independent domestication origins of Eurasian reindeer. Proceedings of the Royal Socociety Series B275: 1849-1855. doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2008.0332

- ↑ Ji, R., Cui, P., Ding, F., Geng, J., Gao, H., Zhang, H., Yu, J., Hu, S. and Meng, H. (2009): Monophyletic origin of domestic bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus). Animal Genetics 40: 377-382. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-2052.2008.01848.x (open access)

- ↑ David Rhode, David B. Madsen, P. Jeffrey Brantingham, Tsultrim Dargye (2007): Yaks, yak Dung, and prehistoric human habitation of the Tibetan Plateau. Developments in Quaternary Sciences Vol. 9: 205-224. doi: 10.1016 / S1571-0866 (07) 09013-6

- ↑ Simon YW Ho, Greger Larson, Ceiridwen J Edwards, Tim H Heupink, Kay E Lakin, Peter WH Correlating Bayesian date estimates with climatic events and domestication using a bovine case study. biology letters 4: 370-374. doi: 10.1098 / rsbl.2008.0073

- ↑ Daniel Haag-Waxckernagel: The dove. Schwabe-Verlag, Basel 1998 ISBN 3-7965-1016-7 p.26

- ↑ Carlos A. Driscoll, David W. Macdonald, and Stephen J. O'Brien (2009): From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA vol. 106 Supplement 1 9971-9978. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0901586106

- ↑ BT Thai, CP Burridge, TA Pham, CM Austin (2004): Using mitochondrial nucleotide sequences to investigate diversity and genealogical relationships within common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Animal Genetics 36 (1): 23-28. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-2052.2004.01215.x

- ^ Eugene K. Balon (1995): Origin and domestication of the wild carp, Cyprinus carpio: from Roman gourmets to the swimming flowers. Aquaculture 129: 3-48.

- ^ CH Wang & SF Li (2004): Phylogenetic relationships of ornamental (Koi) carp, Oujiang Color carp and Long-fin carp revealed by mitochondrial DNA COII gene sequences and RAPD analysis. Aquaculture 231: 83-91.

- ↑ P. Cherry & TR Morris: History and biology of the domestic duck. In: Domestic duck production, science and practice. CABI

- ↑ Beate D. Scherf (Ed.): World watch list for domestic animal diversity. 3rd edition. FAO 2000 ISBN 92-5-104511-9

- ↑ Umberto Albarella (2005): Alternate fortunes? The role of domestic ducks and geese from Roman to Medieval times in Britain. Documenta Archaeobiologiae III. Feathers, Grit and Symbolism (ed. By G. Grupe & J. Peters): 249-258.

- ↑ Mark Beech, Marjan Mashkour, Matthias Huels and Antoine Zazzo (2008): Prehistoric camels in south-eastern Arabia: the discovery of a new site in Abu Dhabi's Western Region, United Arab Emirates. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies Vol. 39, Papers from the forty-second meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies held in London, July 24-26, 2008 (2009), pp. 17-30.

- ↑ Ilse U. Köhler-Roleffson (1991): Camelus dromedarius. Mammalian Species No. 375: 1-8.

- ↑ Fox, JG, RC Pearson, JA Bell: Taxonomy, history and use of ferrets. In Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 2nd Edition, Fox JG Editor, William & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1996, pp. 3-170.

- ↑ Camilla F. Speller, Brian M. Kempb, Scott D. Wyatt, Cara Monroec, William D. Lipe, Ursula M. Arndt, Dongya Y. Yang (2010): Ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals complexity of indigenous North American turkey domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA vol. 107 no.7: 2807-2812. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0909724107

- ↑ Erin Kennedy Thornton, Kitty F. Emery, David W. Steadman, Camilla Speller, Ray Matheny, Dongya Yang (2012): Earliest Mexican Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) in the Maya Region: Implications for Pre-Hispanic Animal Trade and the Timing of Turkey Domestication. PLoS ONE 7 (8): e42630. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0042630

- ↑ Rudolf Piechocki: The goldfish and its varieties . 6th edition. Westarp Sciences, 1990, ISBN 978-3-89432-398-1 (First reports on goldfish under Governor Ting Yen-tsan from 968-975).

- ↑ M. Monnerot, JD Vigne, C. Biju-Duval, D. Casane, C. Callou, C. Hardy, F. Mougel, R. Soriguer, N. Dennebouy, JC Mounolou (1994): Rabbit and man: genetic and historic approach. Genetics Selection Evolution 26 Supplement 1: 167s-182s.

- ^ Hermann von Nathusius: Preliminary studies for the history and breeding of domestic animals, initially on the pig skull . Wiegandt and Hempel, Berlin 1864 ( Google Books)

- ↑ Zeder, Melinda A .: Pathways to Animal Domestication. Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability, 2012, p. 233.

- ↑ Zeder, Melinda A .: Pathways to Animal Domestication. Biodiversity in Agriculture: Domestication, Evolution, and Sustainability, 2012, pp. 233–236 (with 3 illustrations).

- ↑ Duden online: domesticate , see meaning 2.