Codex Dresdensis

The Codex Dresdensis (or Dresden Codex , obsolete Dresden Codex ) is one of the four surviving and definitely authentic Maya manuscripts . It is dated between 1200 and 1250 and is described with hieroglyphics , pictures and numerals . Based on its content, it can be assumed that it is a manual for calendar priests. The codex consists of 39 double-sided sheets that were originally folded as a fan- fold, but are now shown as two strips, each about 1.80 meters long.

The codex is located in Dresden in the book museum of the Saxon State and University Library , where it is the only one of the four Maya codices that can be viewed. The other three authentic codices are kept in Paris ( Codex Peresianus ), Madrid ( Codex Tro-Cortesianus ) and Mexico ( Mexico Maya Codex ).

history

The Codex Dresdensis was acquired in 1739 by the supervisor of the Electoral Library in Dresden, Johann Christian Götze , from a private person in Vienna as an “invaluable Mexican book with hieroglyphic figures”. How the work got to Vienna is not known. A short time later, Götze gave the manuscript to the Electoral Library , which it first published in 1848.

Alexander von Humboldt published his copies of five plates of the work as early as 1810. In 1825 the painter Agostino Aglio signed the Codex in Dresden when he was searching European libraries for Mexican manuscripts on behalf of Lord Edward King Kingsborough . Its reproduction is the first complete reproduction of the Dresden Codex. He also established the page numbering from 1 to 74, which is customary to this day, omitting the four blank pages and separating the codex into two parts. It was not until 1853 that Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg identified the codex as a Maya manuscript .

The Dresden librarian Ernst Wilhelm Förstemann was able to decipher the calendar part between 1887 and 1897. He found out that the Mayan number system was based on a system of twenty ( vigesimal ) and that they used this system to record a daily count of all the days that had elapsed from zero to the respective date. With this he succeeded in the “ long count ” of the Maya with the starting date 4 Ahau 8 Cumuku, the hieroglyphs of the time units Uinal (20 days), Tun (360 days) and Katun (7200 days) as well as the tables of Venus - and to interpret moon orbits . He found the correct reading direction for the Codex as well as the glyphs of the characters for zero and for the planet Venus, with which at the end of the 19th century the calculation method of the Maya and the astronomical relationships in the Codex became recognizable.

Milestones in the subsequent decoding and interpretation of the non-calendar text were the first assignment of hieroglyphs to figures of gods by Paul Schellhas in 1897 and the decoding of the word and syllable characters, among others by Yuri Knorosow in the 1950s. The latter was made possible in particular by the Landa alphabet , which is based on the records of the Bishop of Yucatán , Diego de Landa , from 1566.

As early as 1835, the Codex was glazed on both sides in two parts. The two strips were inserted between the glass plates without spacers and are therefore in direct contact with the glass. Today's partial adhesion of the paint layers to the glazing is due to water damage as a result of the bombing raids on Dresden on February 13, 1945. Due to this glass adhesion, changes in the presented page sequence, such as the correction of three twisted sheets after drying in 1945, are not possible today.

description

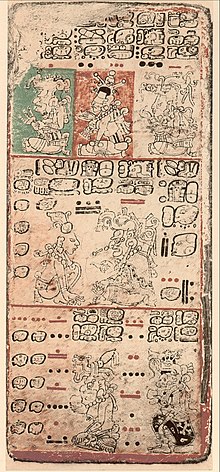

The writing consists of 39 leaves written on both sides. Four of the 78 pages are blank. Each sheet is approximately 8 inches high and 4 inches wide. Between the individual sheets there are thin membranes that connect the sheets with each other so that they can be folded like a folding album ( Leporello ). The codex has a length of 3.56 meters when unfolded. Since 1835 it has been presented in two parts. The first part with 20 leaves is 1.85 meters long, the second with 19 leaves 1.77 meters.

Of the approximately 350 characters in Maya script used in the Codex Dresdensis, approximately 250 have been deciphered. Of these, about 100 syllable characters and about 150 word characters , such as B. the names of gods. Many of the accompanying texts can now be read with it. Most refer to the accompanying images and consist of short sentences of four or six characters. The numbers in the Codex , based on the system of twenty , are made up of points (one), bars (five) and stylized shells (zero).

The characters and images were painted with brushes in different colors on Amatl , a paper-like material made from the bark of the Amatl tree ( Ficus insipida ). This bark paper had previously been covered with a fine white layer of lime as a base for writing.

Emergence

Based on the start and end dates of the astronomical conjunctions, John Eric Sidney Thompson dated the copy to 1200 to 1250. Thus, the codex could come from the northern Yucatán , where the last great Mayan polity existed between 1200 and 1450. A later attribution (15th century) has so far been excluded because steles were found in Chichén Itzá (10th to 12th centuries) whose glyph inscriptions show stylistic similarities to the Dresden Mayan manuscript. Although the Mayan codices that have been preserved come from the post-classical period, the use of books made from ficus bark can already be traced back to the classical period. The word ju'un for "book" is identical in the Mayan languages with the word for " amate ", the writing material of the manuscripts.

The books were folded in leporello form and provided with wooden lids for protection, which were covered with jaguar skin. Inscriptions bearing the nobility title aj k'u jun , “the one of the holy books”, which give clues to the custodians of the manuscripts, testify to the highly developed book culture during the heyday of the Mayan culture (cf. Grube, 1999, p. 84). Research has indications that copies and copies were made in specially designated centers that were intended for the Mayan priests working in the congregations to practice their worship. The white pages in the Codex Dresdensis indicate that the manuscript was not created in a single process, but was continuously completed. Some divination calendars were left incomplete, where to insert the coefficients of the days of the Tzolkin written in red .

Six different writers can be identified in the Dresden Codex based on stylistic criteria: the writer of the figures of the gods (pages 1–3); the writer of the daily almanacs (pages 4–23); the main scribe (pp. 24, 45-74, 29-44); the writer of the New Year's tablets (pages 25–28); the writer of the sacrificial rituals (pages 30–35) and the writer of the Martian tablets (pages 42–45).

Illustration

content

Today it is assumed that the Codex originally consisted of one part, the front and back of which can be read in sequence. Since the page numbering introduced by Agostino Aglio in 1825/26 and still in use today does not take this into account, the historically correct reading order of the pages is the following: 1–24, 46–74, 25–45. Ten chapters can be distinguished in the Codex:

- Introduction to the Codex: Dressing the figures of the gods (pages 1–2), sacrificing Jun Ajaw (page 3), invoking the gods, preparing prophecies (pages 4–15).

- Almanacs of the moon goddess Ix Chel (pages 16–23): goddess of healing who, in some illustrations, carries birds on her back as carriers of diseases. Treatise of Illnesses, Cures, and Dangers of Childbirth.

- Tables of Venus (pages 24, 46–50): Images of the god of Venus as well as information (events, dates, intervals, directions and the associated signs) about the appearance of Venus as morning and evening star over the course of 312 years based on the 584 day - Venus cycle . Venus was considered aggressive; the Venus calendar was probably used to calculate the success of military campaigns.

- Eclipse tables / eclipse tables (pages 51–58): Calculation of the occurrence of lunar and solar eclipses . The eclipses that were predictable for the Maya were regarded as a time of general need and danger, the effects of which one tried to avert through sacrifice and ritual.

- Multiplication tables for the number 78 (pages 58–59). The meaning of this number is unknown.

- K'atun prophecy (page 60): This describes catastrophes that can occur at the end of a katun . In the Maya calendar, a katun was a 20-year period with a specific name that returned after 13 katun cycles, i.e. after 260 years. Then there was the threat of hunger, drought and earthquakes.

Beginning of the back of the codex with its four blank pages.

- Numbers of snakes (pages 61–62), pillars of the cosmos (pages 63–73): The numbers of snakes indicate mythical events over a period of over 30,000 years. The following pages deal with the pillars of the cosmos and various manifestations of the rain god Chaac . The origin of time and the origin of rain belonged together for the Maya. These passages correspond word for word to stone inscriptions from the classical period, for example in the Mayan cities of Palenque and Tikal .

- The Great Flood (page 74): Depiction of a cosmic catastrophe with the destruction of the world by a huge flood. According to the traditions of the Maya, the existing world, the end of which is foretold here, was preceded by three other world ages.

- Beginning of the New Year Ceremonies (pages 25–28): Describes the rituals that the king and priests had to perform during the last five days of the solar year. New Year ceremonies were seen as symbolic new creations of the cosmos after the end of the world.

- Prophecy calendars for agriculture (pages 29–41), journeys of the rain god and Marstafeln (pages 42–45): prophecy calendars contained statements about the weather and harvest and also served as a guide for cultivating the fields. On the final pages 42–45 there are short sections about the journeys of the rain god and Mars with its cyclical movements during a 780-day period . On the last piece of paper there is a multiplication table for the number 91 with a meaning unknown today.

Page numbering and order

Today's usual pagination from 1 to 74 ignoring the four blank pages was introduced by Agostino Aglio when he signed the Codex for the first time in 1825/26. He divided the originally 3.5 meter long manuscript into a Codex A with 24 leaves and a Codex B with 15 leaves. In disregard that first all fronts and only then the backs are to read, his order is based on the front and then the back reading of Codex A , followed by the same reading in Codex B .

The senior librarian KC Falkenstein changed the order in which the sheets were displayed for “spatial and aesthetic reasons” around 1836. In doing so, he created the “two approximately equal parts” available today.

EW Förstemann , who was involved in the deciphering of the Codex, corrected Aglio's error in 1892 by reversing both pages 1/45 and 2/44, with Aglio's pages 44 and 45 correctly becoming pages 1 and 2 of the Codex.

Pages 6/40, 7/39 and 8/38 were rotated when the pages were reinserted after the Codex 1945 had to be dried out during the war.

Others

Venus observations

Pages 24 and 46 to 50 contain pictures of the god of Venus and information about the appearance of Venus as the morning and evening star. This Venus Almanac describes a synodic integral 584-day interval: The 236 days of Venus being visible as the morning star are followed by 90 days of invisibility. After that, Venus can be observed again as an evening star for 250 days before it cannot be seen again for 8 days.

The actual values of the Venus intervals come very close to these Mayan records and are confirmed in the Venus tables of the Ammi-saduqa , which contain almost identical observations of Venus.

World Document Heritage Candidacy

As part of his Latin America activities for the Free State, Alexander Prince von Sachsen-Gessaphe and the then director of the Saxon State Library , Thomas Bürger, delivered a facsimile of the Codex Dresdensis to the Republic of Guatemala on October 22, 2007 in Guatemala City . Germany and Guatemala want to apply to UNESCO to declare the Codices a World Document Heritage .

literature

- The Dresden Maya Calendar: The Complete Codex . Nikolai Grube, Herder Verlag, Freiburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-33332-3

- Codex Dresdensis, An early Maya manuscript in standardized representation . Axel Neurohr, Edition Winterwork, Borsdorf 2011, ISBN 978-3-942693-81-3

- The Dresden Maya manuscript. Special edition of the commentary volume on the complete facsimile edition of the Codex Dresdensis. Akademische Druckerei- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1989, 93 (49) S., ISBN 3-201-01478-8 ; therein Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript and Ferdinand Anders: The Dresden Maya manuscript .

- Codex Dresdensis. Scripture and illumination of the Mayan Indians . Rolf Krusche (editor), Leipzig, Insel Verlag 1962 and 1965 ( Insel-Bücherei 462/1/2)

Web links

- Information from SLUB Dresden on the Dresden Maya Codex

- Complete digital edition of the facsimile Graz 1975

- The writing system in the Codex Dresdensis

- 3D reconstruction and animation of the Codex Dresdensis in different states

- Redrawing the Codex Dresdensis, William Gates 1932

Individual evidence

- ↑ Unbound fascicle books, so from me on the royal. Bibliothec was delivered in January 1740 , Sign .: Vol. A II, No. 10; Compare: The Dresden Maya manuscript. Special edition of the commentary volume on the complete facsimile edition of the Codex Dresdensis. Akademische Druckerei- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1989, ISBN 3-201-01478-8 ; therein Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript , p. 13.

- ↑ a b The Dresden Maya manuscript. Special edition of the commentary volume on the complete facsimile edition of the Codex Dresdensis. Akademische Druckerei- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1989, ISBN 3-201-01478-8 ; therein Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript and Ferdinand Anders: The Dresden Maya manuscript .

- ↑ Alexander von Humboldt : Vues des Cordillères et Monuments des Peuples Indigènes de l'Amérique . Paris, 1810, p. 416, plate 45. Online (fr) .

- ↑ Facsimile of an original Mexican painting preserved in the royal library of Dresden, 74 pages . In: Edward King Kingsborough : Antiquities of Mexico , Volume 3, London: A. Aglio, 1830–1848.

- ^ Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg : Des antiquités mexicaines . In: Revue archéologique 9 (1853), T. 2, p. 417.

- ↑ Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript . In: Codex Dresdensis, commentary . Akademische Druckerei- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1975, pp. 30, 32.

- ↑ Paul Schellhas : The gods of the Maya manuscripts: A mythological cultural image from ancient America . Richard Bertling Publishing House, Dresden, 1897.

- ↑ Yuri V. Knorozov : Maya Hieroglyphic codices . Translated from the Russian by SD Coe. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York at Albany, Pub. No. 8, Albany, NY, 1982.

- ↑ a b The Dresden Codex . 1200-1250. Retrieved August 21, 2013 ..

- ↑ Nikolai Grube : The Dresden Maya Calendar: The Complete Codex . Herder Verlag, Freiburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-33332-3 , p. 57.

- ↑ Nikolai Grube: The Dresden Maya Calendar: The Complete Codex . Herder Verlag, Freiburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-33332-3 , p. 22.

- ^ J. Eric S. Thompson : A Commentary on the Dresden Codex: A Maya Hieroglyphic Book , Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1972, pp. 15, 16.

- ↑ Nikolai Grube: The Dresden Maya Calendar: The Complete Codex . Herder Verlag, Freiburg, 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-33332-3 , p. 33.

- ↑ a b c d e Michael Zick Surprise in the jungle. Bild der Wissenschaft, issue 10/2009, p. 64ff. In it Nikolai Grube: The cosmos in ten chapters online ( Memento of the original from March 8, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Ernst Wilhelm Förstemann : The Maya manuscript of the royal. Public library in Dresden . Naumannsche Lichtdruckerei, Leipzig, p. 7.

- ↑ Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript . In: Codex Dresdensis, commentary . Akademische Druckerei- und Verlags-Anstalt, Graz 1975, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Helmut Deckert: On the history of the Dresden Maya manuscript . In: Codex Dresdensis, commentary . Akademische Druckerei- und Verlag-Anstalt, Graz 1975, p. 41.

- ↑ Guatemala receives a copy of the Codex Dresdensis from SLUB-Kurier via Qucosa, accessed January 18, 2019.

- ^ William Gates: The Dresden Maya Codex: Reproduced from Tracings of the Original Colorings Finished by Hand. Baltimore: The Maya Society, 1932.