Eduard Rottmanner

Eduard Rottmanner (born September 2, 1809 in Munich , † May 4, 1843 in Speyer ) was a German composer and cathedral music director at Speyer Cathedral .

Life

Youth and Education

Eduard Rottmanner's parents' house was at Briennerstrasse 13 in Munich. His father, Franz Xaver Rottmanner, was the accounting commissioner and a cousin of Karl Rottmanner (* 1783) and a nephew of the Bavarian agrarian reformer Simon Rottmanner . As a child, Eduard had a small "menagerie" in his parents' house with pigeons, pheasants and falcons. His diary shows that the family cultivated house music.

At the age of six Rottmanner received piano lessons and at the age of eight he composed his first pieces of music, which were published three years later under the title "Musical experiments and thoughts" . In Nuremberg, where he attended the “Latin School” after the family moved, he received lessons in piano and the beginnings of composing, as well as in violin, clarinet and guitar from the city music director. This was followed by an annual internship at the Oberpostamt in Nuremberg . Back in Munich at the age of 15, Rottmanner attended grammar school and at the same time took lessons in singing, figured bass and organ from court organist Joseph Graetz and Kaspar Ett .

Munich period (until 1839)

After graduating from high school, he perfected himself in English and French and from 1828 studied philosophy, logic, history, physics and statistics at the Munich University . In addition, he continued to take music lessons and held positions as organist in the Munich churches: Bürgersaal , Herzogspital and St. Michael . During this time u. a. his compositions for the melodramas “Die Mühle von St. Aldervon” , “Älpler” , “Die Sendlinger Schlacht” and the beginnings of his opera “Hermann der Liberier” .

His most famous work today, the Rottmanner Pastoral Litany , an impressive setting of the Lauretan Litany , he created at the age of 21. It works through its self-confident vitality and through the transgression of traditional harmony. It is richly orchestrated with horns, oboes, timpani and trumpets alongside the strings. The young composer has structured the monotony of the litany with catchy melodies in such a way that it becomes a lively, festive concert.

Speyer time (1839-1843)

Application and start of activity

In addition to 27 other candidates, Eduard Rottmanner applied for a double position as cathedral music director and seminar music teacher in Speyer at the age of 30 . Bishop Johann Jakob von Geissel decided on him and appointed the young man from Munich as cathedral organist on December 18, 1839. At the same time he had to “lead the singing and ... to conduct the music” in the cathedral , as well as give lessons as a music teacher at the “school teachers' seminar” - the Catholic teacher training institute that had just moved to Speyer. In addition to his undisputed musical abilities, the decisive factor for Rottmanner was the judgment that he had the "necessary teaching skills" and was "an engaging personality with a friendly, serious demeanor and exemplary religious sense" . These qualities seemed particularly important to the bishop, since Rottmanner was supposed to train young teachers as a pedagogue in addition to his job in the cathedral.

Cathedral Kapellmeister and seminar teacher

During the French Revolution, the Palatinate was devastated and the Speyer Cathedral plundered and robbed. Under Napoleon Bonaparte , the French troops used the cathedral church as a cattle shed and material store; In 1806 there were plans to tear it down and use it as a quarry. The Diocese of Speyer was newly formed in 1817 - coinciding with the political boundaries of what is now the Bavarian Rhine District - from the parts of the old Speyer prince-bishopric on the left bank of the Rhine and areas of the dioceses of Mainz , Worms , Strasbourg and Metz . The former hymn books and organ books were still circulating from all these parishes; church music has been paralyzed since secularization . Rottmanners biographer Ludwig Eid states that the Munich musician was seen in the Palatinate as "a kind of musical messiah" , "who should put an end to the previous misery" .

Indeed, contrary to his expectations, the musical conditions in Speyer when Rottmanner arrived were spartan and wild. On January 1st, 1840, at 6 o'clock in the morning, the young musician played in the cathedral for the first time, at the opening of the "twelve-hour prayer". He called the small, completely unsuitable organ a "monkey box", the cathedral and seminar looked poor. His parents are in favor of a new application in Vienna or Munich. Soon, however, a new, excellent organ was set up under Rottmanner's leading and active collaboration. He dedicated it on March 7, 1840. That caused a sensation in the city. Even the Protestants adjusted their church times accordingly and poured into the cathedral. "According to the reports, the impression of the unsurpassable game that followed on the stately work must have been a tremendous one." (L. Eid) Locals and foreign listeners now regularly came to the cathedral outside of the masses, just to hear Rottmanner's game at his afternoon Listen to practice lesson. It became a fixed item on the program for the city's guests. Rottmanner's reputation as an organ virtuoso grew into admiration and soon he was nicknamed "King of the Organ" . (Suffering)

His most difficult task was to build a choir from a crowd of 120 young people who could barely read music, which would do justice to the importance of the cathedral. Rottmanner himself wrote about the difficult undertaking that he has "around 120 singers, big and small, who know as little about the fundamentals of music as the donkey does about striking the lute. However, they have the best will and would accept it if I did instead of the 6 hours per week, of which there would be 60. " With didactic skill Rottmanner reformed the cathedral chant, after all he even rehearsed 12 hours a week. He knew how to inspire the singers and how to motivate the displeased. Their ambition and loyalty to the choirmaster grew quickly. In order to encourage his students, he composed six new masses in 1840 alone, always tailored to their level of knowledge and at the same time suitable for further developing it.

But Rottmanner also had to train his listeners first. The church board of directors as donors and the cathedral chapter were dissatisfied. They wanted "unanimous folk song" and rejected polyphony as unreligious. In the conflict over cathedral music, however, the bishop stood behind his cathedral organist. This responded to the rejection of the church administration with further compositions. The audience was delighted and the critics fell silent. In the meantime in Speyer it was good form to have been to the cathedral on Sundays. On June 10, 1840, after the mass , King Ludwig I recognized the cathedral music director. The inauguration of the Walhalla near Regensburg was accompanied by Eduard Rottmanner's music.

Other work The Domkapellmeister was present in Speyer and in the entire region as a composer and musician at the major festivals of his time. In addition to his involvement in public musical life, he was very popular at the private musical evenings that were very frequent at the time. According to Ludwig Eid, he even amused the most fierce canons with the music genre of the Bavarian Schnaderhüpfl, so far unknown in the Palatinate . His mundane works were now also often performed in southern Germany and even met with approval at court, such as the melodrama “Die Älpler” , which was performed at the Munich Court Theater (now the National Theater).

Seminar music teacher Rottmanner also worked as an employee of the monthly magazine "Der Katholik" , the mouthpiece of the Mainz district that appears in Speyer . This increased his popularity, so that in Bavaria and especially in Munich endeavors were made to make his church music "the rule for the people and a mark for the respective festival day" (L. Eid). Despite the unsatisfactory conditions in his early days in Speyer and the overabundance of tasks, Rottmanner refrained from applying as Kapellmeister elsewhere. He did not want to disappoint the great hopes that had been placed in him in the Palatinate.

He could only compose in his free time, namely at night. During the day he was fully on duty for the diocese, seven days a week. Nevertheless, he created numerous works of his own, mainly sacred music. In doing so, he always pursued the concern of leading people to faith and spirituality through his compositions. Stylistically, he was a typical representative of contemporary romanticism . Often in his profane pieces there is a connection with extra-musical, often literary ideas, e.g. B. in his melodramas.

In order to be able to create a synopsis from 14 old hymn books used there in addition to his extensive work in Speyer, Rottmanner renounced his vacation in Munich twice. He revised the outdated earlier melodies, set new creations to music, most of which were composed by Bishop Geissel, and in 1842, for the first time in the history of the new diocese, published a "Melody Book for the Speyer Diocesan Hymnbook" with 250 songs. At the same time the first uniform diocesan hymn was published. All the songs in later Speyer hymn books - including today's Gotteslob hymns - that do not have a composer, but the indication "Speyer 1842" , are those that Rottmanner composed or at least arranged.

Sickness and death

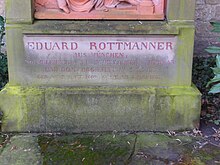

The melody book was to be his last major work. Rottmanner's health suffered from all night long composing. Ludwig Eid reports about it: "At periodic intervals there was a severe headache and made him completely unable to work for five to six hours" . No doctor could help. On May 2, 1843, Rottmanner walked - as often - to the opera in the evening in Mannheim, 27 kilometers away. This time the night return was a pain for him. The following night he fell into deep unconsciousness. He only woke up again for an hour towards evening. He died on May 4, 1843 at the age of 33 and was buried in what was then the municipal cemetery, now the old Speyer cemetery , or Adenauerpark. The autopsy found the cause of death to be a strong, tumor-like blood clot at the base of the cranial cavity and foci of pus in the meninges. Ludwig Eid explains that modern medicine assigns this clinical picture to chronic pachymeningitis, a severe form of inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, which repeatedly causes bleeding and deposits in the brain. Rottmanners tombstone is z. Z. (2009) on the cathedral chapter cemetery next to the St. Bernhard church . Its upper area has been renewed and bears an old terracotta relief by the composing artist, which was apparently once on the outer wall of the cathedral. The grieving parents had donated it and a second copy was once available at the Munich Citizens' Hall Church , but was destroyed in the Second World War. The tragic death of the popular, young cathedral music director shook people at the time: “The coffin was accompanied by a funeral procession that Speyer had not seen in living memory” . (Suffering).

Post fame of the composer

In the whole of Bavaria, which at that time also included the Palatinate, the year 1843 was musically called Rottmanner. Many of his compositions and music manuscripts are in the cathedral library in Speyer. Works by him also appear again and again in various Bavarian / Palatinate parishes. Eduard Rottmanner's music has largely been forgotten today. In the Speyer Cathedral - for which many of his pieces of music were specially written - they were sometimes played up until the time before the Second World War, under the cathedral conductor Peter Drescher .

The melodrama "Sendlinger Battle" was performed again in Munich in 2005 on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of this popular uprising. The “Rottmanner pastoral litany” has remained “the rule of the (ecclesiastical) people” in Munich to this day and is characteristic of two festive days: it can be heard every year on New Year's Eve in St. Peter and on Epiphany in the Bürgersaalkirche. Eduard Rottmanner was the great-uncle of Benedictine Father Odilo Rottmanner , famous preacher and confessor of the royal family, in Munich, St. Boniface.

Works

- Hermann the Liberator, opera

- three melodramas

- the Rottmanner Pastoral Litany (currently the only CD on the Marian Congregation for Men in Munich)

- another six litanies

- 23 choirs

- two requiums

- four overtures

- 13 sonatas

- 14 Latin masses

- eight German trade fairs

- two vespers

- 19 variations

- three fantasies

- 15 proprium chants

- 17 antiphons and hymns,

- two Te Deum

- a resurrection choir

- a song of the mount of olives

- 92 smaller lecture pieces, dances and marches

- and much more

literature

All quotes after:

- Ludwig Eid : The first cathedral music director, Speyer, approx. 1930.

Further:

- Konrad Reither : Festschrift 25 years of school teachers' seminar Speyer, 1864 (separate chapter on Eduard Rottmanner).

- Eid, Ludwig: Eduard Rottmanner, the first seminar music teacher at the school teachers seminar Speyer 1839–1843, Speyer, 1913.

- Speyerer Tagespost, No. 102, from May 4, 1953, "Eduard Rottmanner, the minstrel of God" commemorative article on the 110th anniversary of death.

- Fritz Steegmüller: "History of the Speyer Teacher Training Institute, 1839-1937" , Pilger-Verlag, Speyer, 1978.

- Deny, Simone: Eduard Rottmanner and the Speyer Cathedral Music in the first half of the 19th century, Landau, 1992.

- Some notes about Eduard Rottmanner, State Library Munich, manuscript collection

- The structure of the cathedral choir and seminar music teacher and cathedral music director Eduard Rottmanner 1839–1843 in Fritz Steegmüller: "1000 Years of Musica Sacra at the Episcopal Church in Speyer", Pilger-Verlag Speyer, 1982.

Web links

- Ave Maria No. 1, 2 and 3 as audio sample on the piano (click on the "Listen" symbol)

- Audio sample melody sequence (without text), Mass in A major by Eduard Rottmanner. ( MID ; 72 kB)

- Estate in the Bavarian State Library

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rottmanner, Eduard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German church music composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 2, 1809 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 4, 1843 |

| Place of death | Speyer |