Falun Gong outside mainland China

This article is about Falun Gong outside of China . Falun Gong, also called Falun Dafa, is a qigong practice that combines meditation with the moral philosophy formulated by founder Li Hongzhi and spread throughout China in 1992 . Li first gave lectures abroad in 1995 in Paris and Sweden . At the invitation of the Chinese ambassador to France, Li gave a lecture on his teachings and practice methods for embassy staff. From then on, Li gave lectures in other major cities in Europe, Asia, Oceania and North America. He has lived in the United States since 1998. Falun Gong is practiced in around 70 countries around the world today, and the teachings have been translated into over 40 languages. The international Falun Gong community is estimated in the hundreds of thousands, but the estimates are imprecise due to the lack of formal membership.

Although first praised and promoted by the Chinese Communist Party , it started the persecution of Falun Gong in mainland China in 1999 . In response, Falun Gong practitioners around the world hold activities to educate the public about human rights issues related to them. This includes lobbying, handing out leaflets, taking part in sit-in strikes in front of Chinese embassies and consulates, and holding parades and demonstrations. They set up media centers, advocacy groups and research organizations to cover the persecution in China, and filed complaints against the architects and participants in the persecution campaign.

Several foreign governments, the United Nations, and human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have expressed concern over allegations of torture and ill-treatment of Falun Gong practitioners in China. Nonetheless, some observers noted that Falun Gong failed to gain the sympathy and international attention that Tibetans , Chinese Christians or democracy activists have shown. This is attributed to the group's poor knowledge of public relations, to the effects of the Communist Party's propaganda against this practice, and to the teaching that seems strange to Western observers and identifies with Buddhist and Daoist traditions.

history

From 1992 to 1994, Li Hongzhi traveled all over China, giving weekly seminars on Falun Gong's spiritual philosophy, and teaching the exercises and meditation practice. In late 1994, he announced that he had finished teaching the practice in China and that the content of his lectures would be published in the January 1995 book Zhuan Falun. Later that year, Li left China and began to spread his teachings abroad. He started at the Chinese Embassy in Paris in March 1995, followed by three lectures in Sweden in May 1995. Between 1995 and 1999, Li lectured in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Switzerland and Singapore. Falun Gong associations have been established in Europe, North America, and Australia. The activities took place mainly on university campuses. ;

As the practice began to proliferate outside of China, Li received recognitions in the United States and other parts of the western world. In August 1994, the City of Houston named Li an Honorary Citizen and Special Envoy for his "altruistic public service for the welfare of mankind." In May 1999, Li was welcomed to Toronto by the mayor and governor general of the province. In the following two months, Li also received awards from the Chicago and San Jose administrations .

Translations of the Falun Gong teachings began in the late 1990s. Although the practice began to attract a foreign following, it remained relatively unknown in the Western world until the spring of 1999 when tension between Falun Gong and the Communist Party became a topic of international media coverage. Because of this increased awareness, the practice also gained a wider following outside of China. After the Communist Party's persecution of Falun Gong began, overseas presence became important to the resistance of the practice in China and its continued survival.

organization

Falun Gong has a minimal organizational structure and no rigid hierarchy, places of worship, fees, or formal membership. Falun Gong's doctrinal meaning is purposely "informal" and has little to no material or formal organization. Falun Gong practitioners are prohibited from collecting donations or collecting fees for the practice, and are also prohibited from teaching or interpreting the teachings for others.

In the absence of membership or initiation rituals, anyone who chooses to become a Falun Gong practitioner can become a Falun Gong practitioner. Students take part in the practice and follow their teachings as much or as little as they want, and practitioners do not tell others what to believe or how to behave.

It can be said that Falun Gong is highly centralized, that there is no spiritual or practical division of authority. Li Hongzhi's spiritual authority within the practice is absolute, but the organizational structure of Falun Gong is against totalitarian control. Li does not interfere in the personal lives of practitioners who have little or no contact with him except through studying his teachings. Volunteer assistants or liaison officers coordinate local activities but have no authority over other practitioners regardless of how long they have been practicing Falun Gong. You are not allowed to raise money, perform healing or teach others.

Falun Gong's unclear structure and lack of membership make it difficult to grasp the scope and size of Falun Gong communities outside of China. Local groups post the times and locations of their practice sites on Falun Gong websites, but do not try to find out how many practitioners there are in certain places. University of Montreal historian David Ownby noted that there are no "middle or upper levels of organization where you can get such information." Ownby says that practitioners are not "members" of any "organization" and have never filled out any forms.

As far as one can speak of an organization in the case of Falun Gong, this is in part achieved through a global, networked and often virtual community. In particular, electronic communications, email lists, and a collection of web pages are the primary means of coordinating activities and disseminating Li Hongzhi's teachings. In addition to spreading the teachings, the Internet is used to maintain and nurture the community and as a medium to inform about the persecution in China. Practitioners maintain hundreds of websites around the world. Most contain content in both Chinese and English; other languages are German, French, Russian, Portuguese, Spanish, Japanese and others.

Falun Gong relies on the Internet as a means of organization, which has led some observers to refer to the group as a "virtual religious community," although other scholars are skeptical as they believe the importance of the Internet is overstated. Scott Lowe, for example, believes that the Internet is not an essential factor in attracting people to the practice. Instead, the influence of family and friends, as well as the prospect of better health, seem to be much more important to taking an interest in Falun Gong.

Although the spiritual practice of Falun Gong does not have a clear organization, Falun Gong practitioners have collaborated considerably since 1999, establishing their own research and advocacy groups, media groups, and art companies.

Group practice and learning

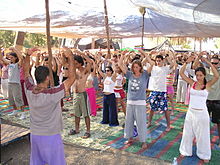

Outside mainland China, there is a network of volunteer contacts, regional Falun Dafa associations, and university clubs in about 70 countries. In most medium and large cities, Falun Gong practitioners hold regular meditation or study seminars where they practice the Falun Gong exercises and read (or reread) Li Hongzhi's writings. The practice and meditation meetings are described by practitioners as informal groups that usually gather in the morning for one to two hours in public parks. Group reading usually takes place in the evenings in private apartments, classrooms at universities or high schools. David Ownby describes what Falun Gong offers as "something that is closest to a regular 'church experience'". People who are too busy, isolated, or who simply prefer solitude, may choose to practice alone.

Large Falun Gong experience sharing conferences are held every few months in major metropolitan areas, where Falun Gong students read prepared accounts of their experiences with the practice. These conferences, which can attract thousands, also provide a venue for Li Hongzhi to speak to practitioners.

Evangelism

Falun Gong practitioners are encouraged to engage in Hong Fa activities, which can be translated as "making known the way." The Chinese term "Hong Fa" can be roughly interpreted as referring to a kind of "conversion". However, because Falun Gong instills the belief that individuals are either predestined or not to receive the practice, Falun Gong practitioners do not actively seek to convert people. Hong Fa activities include handing out leaflets, leaving Falun Gong literature in shops, libraries, and so on, and participating in activities such as marches, parades, and Chinese cultural events.

Demographics

Ownby confirms that Falun Gong is practiced by hundreds of thousands of people outside of China. The largest communities are in Taiwan and in North American cities, which have large Chinese populations like New York and Toronto. Sociologists Susan Palmer and David Ownby did demographic research in North American communities that found that 90 percent of practitioners were ethnic Chinese (there are proportionally more Caucasians in Europe). The mean age was around 42. 56% of the respondents were female and 44% were male; 80% were married. The study noted that respondents were highly educated: 9% were PhDs in Philosophy, 34% had a Masters degree, and 24% had a Bachelor degree.

Most of the Falun Gong practitioners in North America are among the Chinese students who emigrated in the 1980s and 1990s. Craig Burgdoff, in his ethnographic research of practitioners in Ohio, finds that 85 to 90% were Chinese students or their family members. Similar results from North American practitioners were suggested by Scott Lowe, professor of philosophy and religious studies at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. In an Internet survey in 2003, Lowe found that Chinese respondents living in Western nations "were uniformly well educated and clearly represented the overseas elite," with all respondents holding masters degrees or higher. Respondents from Singapore and Malaysia had a mixed educational profile, with the minority having university degrees.

The majority of North American practitioners learned Falun Gong after leaving China. Ownby indicated that Falun Gong appeals to a wide range of social groups, "including university professors and students, high party and government officials, well-educated cadres and members of the comfortable middle class, and [...] the old, the weak, the unemployed and the desperate." of typical Chinese practitioners who are likely retired, Ownby found in polls at practitioners' conferences in Montreal, Toronto, and Boston between 1999 and 2002 that the average Chinese practitioner in North America was "young, urban, and dynamic." Non-Chinese Falun Gong practitioners are more likely to display a profile of nonconformists and "spiritual seekers"; People who tried a variety of qigong, yoga, or religious practices before they found Falun Gong. This is in contrast to the standard Chinese profile, which Ownby described as “the straightest of the straight arrows”.

Reasons for practicing Falun Gong

In surveys of Falun Gong practitioners in North America, the most common reasons why practitioners were attracted to the practice were for the teachings, cultivation exercises, and health benefits. In a study conducted by David Ownby, nearly 30% of practitioners said they were attracted to the "intellectual content" of Falun Gong, 27% because of "spiritual enlightenment", 20% because of "health benefits," 15% because of the Exercises, 7% because of Li Hongzhi himself and 2% because of the community. The "intellectual content", according to Ownby, refers to the value of the Falun Gong teachings in describing the "workings of the moral and physical universe."

Scott Lowe's survey found that the spiritual teachings of Falun Gong and the promise of good health were the most common reasons people started practicing. In Lowe's study, 22 respondents said that "Master Li's Philosophy and His Answers to Life's Most Difficult Questions" were their primary attraction to the practice, while another twenty had been drawn to the health benefits. Nine were attracted to moral principles, twelve to the books, ten to the exercises, and few others to a variety of other factors. Several respondents apparently recognized that other forms of qigong were "mindless, exoteric and superficial" while believing that Falun Gong was "the most complete, effective, and comprehensive system of spiritual cultivation on the planet."

In Lowe's survey, practitioners were asked whether their attraction to the Falun Gong practice had changed over time. Ten of them who started practicing with the intention of attaining enlightenment claimed that they had not seen any change. Others, over time, placed less emphasis on the health improvements they had experienced, which they viewed as "a relatively trivial result of cultivation." Twenty-six respondents said they had a new sense of moral certainty and spiritual growth, and ten others discovered "a firm determination to continue their cultivation to the goal of enlightenment or perfection, no matter what obstacles may appear in their path."

Foreign Responses to the Persecution in China

In July 1999, the Communist Party launched a campaign to persecute Falun Gong, including through extra-legal detention, torture, and other coercive measures and propaganda. Falun Gong communities in and outside of China have since used a variety of methods to resist and mitigate the persecution in China. These tactics range from engaging with the media, lobbying governments and non-governmental organizations, to public protests and demonstrations, and seeking redress. As the persecution in China progressed, Falun Gong practitioners overseas increased their efforts and sought support from Western human rights organizations, emphasizing the implications of freedom of expression, assembly and conscience.

Legal Initiatives

Lawyers helped Falun Gong practitioners around the world file dozens of largely symbolic lawsuits against Jiang Zemin , Luo Gan and other Chinese officials for genocide and crimes against humanity. According to the International Advocates for Justice , Falun Gong filed the largest number of human rights lawsuits in the 21st century, among the most serious international crimes defined by international criminal law. As of 2006, 54 civil and criminal proceedings were carried out in 33 countries.

In some cases, courts refused to recognize Falun Gong cases against Chinese officials on the grounds of sovereign immunity. In November 2009, however, Jiang Zemin and Luo Gan were charged by a Spanish court with genocide and crimes against humanity and their involvement in the persecution of Falun Gong. A month later, an Argentine judge concluded that Jiang and Luo had used a genocidal strategy in the persecution and extermination of Falun Gong and asked Interpol to arrest them.

In May 2011, Falun Gong practitioners filed criminal charges against technology giant Cisco Systems . The ad, based primarily on internal Cisco documents, claimed that the tech company "designed and implemented a surveillance system for the Chinese Communist Party, even though it knew it would be used to exterminate members of the Falun Gong religion." subject it to incarceration, forced labor, and torture. ”Cisco denied having manufactured its products to facilitate censorship or repression.

In addition to legal charges of great public concern against Chinese officials and corporations, Falun Gong practitioners filed a variety of complaints and civil suits. It concerned discrimination outside of China, most of which took place in the Chinese diaspora community. Several complaints were made after Falun Gong groups were prevented from participating in parades or other activities. In Canada and New York, Falun Gong practitioners won sentences against Chinese companies and community organizations that discriminated against them based on their religious beliefs.

Falun Gong practitioners have been involved in a series of defamation lawsuits against Chinese-language media and agents of the Chinese government. In 2004, Canadian Falun Gong practitioner Joel Chipkar won a libel case against Pan Xinchun. Pan was an official at the Chinese Consulate in Toronto who described Chipkar as a member of a "dark cult" in a newspaper article. Pan was ordered to pay $ 10,000 in damages to Chipkar, but he left the country without paying. In 2008, the Quebec, Canada Appeals Court ruled that the Chinese newspaper Les Presses Chinoises slandered Falun Gong by portraying the practice as dangerous and perverse. However, the court did not allow any claims for damages on the grounds that the defamation was against the group and not against individual plaintiffs.

Media organizations

In the early 2000s, Falun Gong practitioners in the United States began setting up their own Chinese-language media organizations in order to gain greater exposure to their cause and challenge the dominant Chinese state-controlled media. These include the Epoch Times newspaper , New Tang Dynasty Television and the Sound of Hope radio station. In addition to content related to Falun Gong, they became critics of communist party politics in general, covering other human rights issues in China, corruption, environmental and health issues, and other topics. According to communications professor Yuezhi Zhao, these media organizations are an example of how Falun Gong has entered the "de facto media alliance" with the exiled democracy movements in China. This is evident in frequent articles by prominent mainland China critics who live abroad.

Although originally established to address the needs of the Chinese media market, media organizations expanded into many additional languages. The Epoch Times newspaper is represented in more than 30 countries in 17 languages, and NTD Television has satellite and cable coverage in North America, Europe and Asia and produces programming in 18 languages. The media is not formally affiliated with Falun Gong, which lacks both central organization and resources. However, most of their staff are Falun Gong practitioners and many work on a voluntary basis.

Demonstrations and sit-in strikes

After the persecution campaign began in 1999, practitioners outside of China frequently started holding protests, rallies, and appeals. These include large-scale marches, demonstrations, and vigils that coincide with notable anniversaries such as April 25, 1999 and July 20, 1999. During the marches, participants typically hold signs and banners, and different sections of the parade are devoted to different aspects of the pursuit. There is usually a section with participants wearing only white clothes that symbolize grief and holding photos of practitioners killed in China.

Practitioners also hold sit-in strikes and demonstrations in front of Chinese embassies and consulates. Falun Gong practitioners in Vancouver , Canada continue to hold the longest, continuous protest against the persecution, held twenty-four hours a day at the entrance of the Consulate of the People's Republic of China on Granville Street. In June 2006, the Mayor of Vancouver announced that the protest signs and structures would have to be removed, in accordance with local statutes against the construction of permanent structures on public property. In 2010, the British Columbia Court of Appeals ruled that the city's order to remove the protest structures was unconstitutional. The superstructures were restored.

Anniversaries of significant dates of the persecution are marked by protests from Falun Gong communities around the world. For example, in Washington, DC , the anniversary of July 20, 1999 is marked by a rally in the US capital and attended by several thousand practitioners. Diplomatic visits by high-ranking Chinese officials have also faced demonstrations by Falun Gong practitioners.

Parades

Unlike marches, which focus on drawing attention to the persecution in China, the solemn Falun Gong parades include traditional Chinese dances, costumes, chants, exercise demonstrations, drums, pageants, and banners. Practitioners regularly hold parades or public displays of Chinese cultural performances, coinciding with May 13, the anniversary of the first public teaching in China. Practitioners also use various parade events around the world to promote their group and their message.

Arts and Culture

A number of Falun Gong practitioners and organizations outside of China are committed to promoting the classical visual and performing arts. Practitioners portray Falun Gong as part of the broader cultural tradition that led to Chinese arts that have been persecuted and attacked under the rule of the Communist Party.

Falun Gong practitioners who are trained in the fine arts hold displays of their works as the embodiment of their beliefs and practices and to spread the word about the persecution in China. These include Zhang Cuiying, an Australian painter who was imprisoned in China for practicing Falun Gong, and Zhang Kunlun, a Canadian citizen and former professor who was also imprisoned in China. Zhang Kunlun is part of a collective of twelve Falun Gong artists whose exhibition "The Art of Zhen Shan Ren" is touring internationally.

In 2006, Falun Gong practitioners with backgrounds in Chinese classical dance and music founded Shen Yun Performing Arts in New York State . Shen Yun today comprises five separate companies of dancers and musicians who tour internationally. The stated mission is to "Revive 5000 Years of Divinely Inspired Chinese Culture". Shen Yun's performance programs consist of classical Chinese dance, ethnic folk dance, solo musicians and singers, and narrative dances. Shen Yun local performances are often presented by the host city's Falun Dafa Association.

New Tang Dynasty Television, founded by Sino-American Falun Gong practitioners, runs a series of programs to promote "appreciation and awareness of traditional Chinese culture." In 2008, the station began to introduce a series of annual competitions for ethnic Chinese participants. The competitions focus on Chinese classical dance, martial arts, traditional clothing design, painting, music, photography and Chinese cuisine.

Research and Defense Organizations

Falun Gong supporters and practitioners set up a number of research and advocacy organizations involved in reporting human rights violations in China and relaying this information to Western governments, non-governmental organizations, and multilateral organizations. These include the Falun Dafa Information Center , a volunteer-run organization that presents itself as the "official source for Falun Gong and the human rights crisis in China," and largely functions as a press department that publishes press releases and annual reports. The Falun Gong Human Rights Working Group is conducting similar research and reporting on the persecution in China. Their results are often presented to the United Nations. The World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong in China (WOIPFG) is a research institution committed to investigating "the criminal behavior of all institutions, organizations, and individuals involved in the persecution of Falun Gong." Falun Gong supporters and sympathizers also formed groups, such as Friends of Falun Gong and the Coalition to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong in China .

Bypass tools

Around the beginning of the persecution in 1999, the Chinese authorities began to establish and strengthen a system of internet censorship and surveillance called the " Golden Shield Project ." Since then, information about Falun Gong has been a major target of censorship and surveillance on the Internet. Several Falun Gong practitioners were reportedly arrested and detained in prisons or labor camps for posting or even downloading information on the Internet.

In 2000, North American computer scientists who practice Falun Gong began developing evasion and anonymization tools to enable practitioners in China to access information about Falun Gong. Their software tools, such as Freegate, GPass, and Ultrasurf , have now become popular means even for non-practitioners to bypass government controls on the Internet in some other countries.

Other initiatives and campaigns

Falun Gong practitioners launched a number of other campaigns to raise awareness of the persecution of Falun Gong in China. A notable example is the Human Rights Torch Relay, which traveled through over 35 countries in 2007 and 2008, ahead of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. The torch relay was intended to draw attention to a number of human rights issues in China related to the Olympics, particularly those related to Falun Gong and Tibet . The torch relay received support from hundreds of parliamentarians, former Olympic medalists, human rights groups and other affected organizations.

Some Falun Gong practitioners both inside and outside of China are involved in promoting the Tuidang movement . This is a dissident phenomenon that was sparked by a series of articles in the Epoch Times in late 2004. The movement is encouraging Chinese citizens to quit the Chinese Communist Party, including retrospectively from the Chinese Communist Youth Association and the Young Pioneers . Falun Gong practitioners outside of China make phone calls to China or faxes to mainland China to inform citizens of the movement and the withdrawal declarations.

Attempts at persecution abroad by the Communist Party

The Communist Party's persecution campaign against Falun Gong has expanded to include diaspora communities, including the use of the media, espionage and surveillance of Falun Gong practitioners, harassment and violence against practitioners, diplomatic pressure on foreign governments, and hacking of foreign websites . A defector from the Chinese Consulate in Sydney, Australia, testified, "The war on Falun Gong is one of the main tasks of the Chinese mission abroad."

In 2004, the United States House of Representatives unanimously passed a resolution condemning the attacks against Falun Gong practitioners in the United States by Communist Party agents. The resolution reported that party members "pressured local elected officials in the United States to refuse or withdraw their support for the spiritual Falun Gong group." Also, that the homes of Falun Gong speakers were broken into. and people who took part in peaceful protests outside of Chinese embassies have been assaulted.

The overseas campaign against Falun Gong is described in documents from China's Overseas Chinese Affairs Office . In a report from a meeting of OCAO directors at the national, provincial, and local levels in 2007, the office stated that it was "coordinating the launch of anti-Falun Gong struggles overseas." This office exhorts Chinese foreign nationals to participate in "the rigorous implementation and execution of the party line, the Party's guiding principles and the Party's policies" and to aggressively expand the "fight against Falun Gong, ethnic separatists and Taiwanese independent activists overseas". Other party and state organs believed to be involved in the overseas campaign include the Ministry of State Security (China) , the 610 Office and the People's Liberation Army .

Surveillance and espionage

In 2005, Chen Yonglin, a political consul with the Chinese Consulate in Sydney, Australia, and Jennifer Zeng , a Falun Gong victim of torture in China, sought asylum in Australia. They alleged that Chinese agents were involved in large-scale operations to intimidate and undermine support for Falun Gong outside of China. Chen claimed that his primary role at the consulate was to monitor and harass Falun Gong and to ensure that the practice received little support from the Australian media and elected officials. Zeng said that "espionage and intimidation against Falun Gong practitioners abroad are so widespread that many of us are used to it."

Hao Fengjun, another defector in Australia who worked for the 610 Office in Tianjin City, claimed that his job was to collect and analyze intelligence reports on Falun Gong in Europe, Australia, and North America. The implication was that local 610 Offices are involved in spying overseas. Li Fengzhi, another defector from the Chinese Ministry of State Security who carried out both national and international espionage activities, claimed that the suppression and surveillance of Christian and Falun Gong practitioners in hiding was a focus of the ministry.

In 2005, an agent from the Ministry of State Security who worked with the Chinese Embassy in Berlin recruited a German Falun Gong practitioner, Dr. Dan Sun, as an informant. The agent reportedly arranged for Sun to meet two men posing as Chinese medicine scholars interested in studying Falun Gong. Sun agreed to share information with her in the ostensible hope of deepening her understanding of the practice. However, the men were actually high-level agents from the Shanghai 610 Office. Sun claimed he was unaware that the two men he corresponded with were Chinese intelligence agents, yet he was convicted of espionage in 2011. According to Der Spiegel newspaper , the case had shown "the importance of the [Chinese] government to fight Falun Gong" and "points to the extremely offensive approach sometimes taken by Chinese intelligence services."

On the black list

According to reports, Chinese authorities maintain lists of prominent foreign Falun Gong practitioners and use these blacklists to impose travel and visa restrictions on practitioners. Chen Yonglin, the defector at the Chinese Consulate in Sydney, testified in 2005 that around 800 Australian Falun Gong practitioners had been blacklisted. Chen claimed he tried to remove most of these names from the list.

In order to prevent potential protests during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the authorities blacklisted foreign Falun Gong practitioners and prevented them from traveling to China. 42 other categories of people, including Tibetans and "counter-revolutionary people", were also blacklisted. Chinese authorities tolerated Bibles and other religious items at the Olympics, but not Falun Gong materials. Before the Olympics, the Chinese public security forces requested lists of Japanese Falun Gong practitioners from the Japanese government. However, the request was denied.

In June 2002, when Jiang Zemin visited Iceland , the Icelandic authorities complied with the Chinese government's demands to deny entry to Falun Gong practitioners who wanted to enter the country to protest. With a blacklist provided by China, hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners were rejected or even detained by the Icelandic airline if they managed to get into the country. The blacklist sparked protests by Icelandic citizens and MPs, who then demonstrated in place of Falun Gong practitioners and apologized in a newspaper for their government's actions. In 2011, Iceland's Foreign Minister Össur Skarphéðinsson issued an apology for violating the freedom of expression and movement of Falun Gong practitioners.

In August 2010, an airline employee of the Australian airline Qantas was demoted to short-haul flights after Chinese officials in Beijing threatened her, even though she had flown there several times.

Although Falun Gong is openly practiced in Hong Kong , Falun Gong practitioners from abroad have reported that they have been banned from entering the country. In 2001, Hong Kong officials admitted that they had used a blacklist to deny entry to about 100 Falun Gong practitioners when then Communist Party leader Jiang Zemin visited. In 2004, a Canadian Falun Gong practitioner on a book tour was denied entry to the territory, and in 2008, two Falun Gong practitioners from the United States and Switzerland were separately denied entry while on business and research trips.

In 2003, 80 Taiwanese practitioners were prevented from entering Hong Kong, and in 2007 hundreds of Taiwanese were again prevented from entering Hong Kong or arrested at the airport. These events sparked a six year long human rights case that examined the integrity of the One Country, Two Systems arrangement. In 2009, Falun Gong's case against the Hong Kong Immigration Service was dismissed. Months later, Hong Kong immigration officials refused visas to several members of the Falun Gong affiliated Shen Yun Company, which was supposed to perform on the territory in January 2010. Democratic Party leader Albert Ho said the visa denial was a worrying new erosion of freedoms in Hong Kong and damaging Hong Kong's reputation for being a liberal and open society. A court ruling in March 2010 overturned the immigration authorities' decision.

Disruption and monitoring of electronic communications

Since 1999, Falun Gong practitioners outside of China have reported that their phone lines have been tapped and electronic correspondence has been monitored. Falun Gong websites outside of China were the earliest targets of Chinese denial-of-service attacks , according to Chinese Internet expert Ethan Gutmann . In 2011, dated archive footage was broadcast on China Central Television of People's Liberation Army personnel attacking Falun Gong websites in the United States.

violence

There have been reports of isolated incidents of violence against Falun Gong practitioners by Chinese government agents outside of China, although links with Chinese authorities are sometimes difficult or difficult to confirm.

In September 2001, five Falun Gong practitioners were attacked while peacefully demonstrating outside the Chinese consulate in Chicago. The attackers, who were later convicted of assault, were members of a Sino-US association with ties to the Chinese consulate. In 2002, 25-year-old practitioner Leon Wang from Ottawa reported that he was dragged into the Chinese Embassy, where he was kicked and beaten after he was caught holding an anti-Falun Gong exhibition there photographed. The message replied that Wang "snuck in and interrupted the normal course of the incident."

In June 2004, Australian Falun Gong practitioner David Liang was shot and injured in South Africa from a car that drove past him. The purpose of his visit was to protest outside the meeting of the Africa-China Binational Commission and to file charges against high-ranking Chinese officials for their involvement in the persecution of Falun Gong. Practitioners testified that the shooting was an assassination attempt and that the attackers made no attempt to rob them. Chinese Embassy officials denied involvement. In December 2005, Argentine Falun Gong practitioners filed a criminal complaint against former 610 Office chief and Politburo member Luo Gan while he was visiting the country. During Luo's visit, practitioners were beaten by Chinese attackers in Buenos Aires' Congress Square. The police are reported to have been ordered not to intervene. The Argentine director of Amnesty International indicated that the attacks "were linked to officials from the Chinese government".

In the spring and summer of 2008, Falun Gong practitioners in New York became the target of ongoing violence, mostly in the Chinese neighborhood of Flushing , Queens . Groups of Chinese people reportedly attacked Falun Gong practitioners and threw stones at them, resulting in multiple arrests. The Chinese Consul General in New York, Peng Keyu, allegedly incited the violence against Falun Gong and gave the attackers "instructions".

Diplomatic and Commercial Printing

Party state officials, who typically operate through China's diplomatic missions abroad, exerted diplomatic and economic pressure on foreign governments, media organizations and private companies because of Falun Gong.

In North America, Chinese agents went to newspaper offices to "extol the virtues of communist China and the evil of Falun Gong." There have also been cases where international media organizations have canceled programs and articles related to Falun Gong as a result of requests from the Chinese government. For example, in 2008 the Canadian broadcaster CBC / Radio-Canada succumbed to pressure from the Chinese Embassy in Ottawa and withdrew a documentary about Falun Gong hours before it was due to air. From 2009 to 2010, the Washington Post commissioned an editorial on Falun Gong. The article was deleted "immediately after the Chinese embassy became aware of it," according to journalist Peter Manseau.

Chinese diplomats also warn politicians not to support or recognize Falun Gong, threatening that their support for Falun Gong will jeopardize trade relations with China. In 2002, The Wall Street Journal reported that hundreds of American communities had received letters from Chinese diplomatic missions abroad trying to force them to avoid or even persecute Falun Gong using approaches that "combined gross disinformation and scare tactics." in some cases implied diplomatic and commercial pressure ”.

According to Perry Link, pressure on Western institutions is also taking on more subtle forms, including academic self-censorship, avoiding research into Falun Gong because it could result in denial of visa for research in China. Ethan Gutmann noted that media organizations and human rights groups are censoring themselves on the attitude of the People's Republic of China government towards the practice, fearing the potential repercussions that would ensue if they openly take a stand on behalf of Falun Gong.

Governments and private companies have also been pressured by China to censor Falun Gong practitioners' media organizations. For example, the French satellite operator Eutelsat stopped the Asian broadcasts of the New Tang Dynasty Television in 2008 under pressure from the Chinese state administration for radio, film and television. The move was seen as consideration for trying to secure access to the Chinese market.

In 2011, under pressure from the Chinese authorities, the Vietnamese government tried two Falun Gong practitioners who operated a shortwave transmitter and transmitted information to China. The couple were charged with illicit broadcasting and sentenced to two and three years in prison. Earlier that year, another radio station operated by Falun Gong practitioners in Indonesia , Radio Erabaru, was shut down under diplomatic pressure from China.

International answer

Western governments and human rights organizations condemned the repression in China and understood the plight of Falun Gong. Since 1999, members of the United States Congress have made public statements and several resolutions in support of Falun Gong have been passed. In 2010, House Resolution 605 described Falun Gong as a series of "spiritual, religious, and moral teachings for daily life, meditation, and exercises based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance," and called for "an immediate end the Campaign to Persecute, Intimidate, Imprison and Torture Falun Gong Practitioners ”. The resolution also condemned the efforts of the Chinese authorities to spread "false propaganda" about the practice around the world, and expressed compassion for the persecuted Falun Gong practitioners and their families.

The United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Torture, Extrajudicial Executions, Violence Against Women, and Freedom of Religion or Belief issued numerous reports condemning the persecution of Falun Gong in China and relayed hundreds of worrying cases to Chinese authorities. For example, the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings wrote in 2003 that reports from China “describe painful scenes in which prisoners, many of whom are Falun Gong practitioners, died as a result of severe abuse and denial of medical attention. The cruelty and brutality of these torture methods defy description ”. 2010, the Special Rapporteur condemned for religion and belief, Heiner Bielefeldt, the defamation of religious minorities, and attacked while the governments of Iran and China for its treatment of the Bahá'í Faith -Glaubens or Falun Gong out. "Small communities such as Jehovah's Witnesses , Bahaitum, Ahmadiyya , Falun Gong and others are sometimes branded as 'cults' and they often encounter social prejudices that can escalate into full-blown conspiracy theories," Bielefeldt said at the UN General Assembly.

Although the persecution of Falun Gong has resulted in significant condemnation outside of China, some observers note that Falun Gong has failed to gain the level of sympathy and sustained attention that other Chinese dissident groups have been able to gain. Katrina Lantos Swett, vice chair of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, noted that most Americans know about the persecution of "Tibetan Buddhists and unregistered Christian groups or pro-democracy and freedom of speech advocates like Liu Xiaobo and Ai Weiwei," yes "Little or nothing about China's attack on Falun Gong".

From 1999 to 2001, Western media coverage of Falun Gong, and particularly the mistreatment of practitioners, was frequent. In the second half of 2001, however, the number of media reports fell sharply. By 2002, coverage of Falun Gong by major news organizations such as the New York Times and Washington Post had almost completely ceased, particularly within China. In a study of media reports on Falun Gong, researcher Leeshai Lemish found that Western news organizations were less balanced and neutral and were more uncritical about the Communist Party's stories than about Falun Gong or human rights groups.

Adam Frank writes that the overseas media have used a variety of different modes of presentation in reporting on Falun Gong, including linking Falun Gong to historical ancestors in China, reporting on human rights violations against the group, and reporting real-life experiences with Falun Gong . Ultimately, Frank writes that when it comes to coverage of Falun Gong, the Western tradition of labeling the Chinese as "exotic" dominated and that "the facts were generally correct, but the normality of the millions of Chinese practitioners associated with the practice were brought as good as disappeared ”. David Ownby notes that sympathy for Falun Gong is further undermined by the effect of the "cult label" applied to the practice by the Chinese authorities, which has never completely disappeared in the minds of some westerners and whose stigma still plays a role plays in the public perception of Falun Gong.

China analyst Ethan Gutmann, who has been reporting on China since the early 1990s, tried to explain the apparent lack of sympathy for Falun Gong, partly due to the group's inadequacies in public relations. Unlike the democracy activists or Tibetans, who have found a comfortable place in the Western perception, "Falun Gong marched to a clearly Chinese drum," said Gutmann. This, coupled with Western skepticism about persecuted refugees, led to the view that Falun Gong practitioners tend to exaggerate or even "give slogans instead of facts." Gutmann also noted that Falun Gong had not received stable support from American constituencies that normally support religious freedom: Liberals distrust the conservative morality of Falun Gong, Christian conservatives do not give the practice the same space as persecuted Christians, and the political center is cautious not to disrupt economic and political relations with the Chinese government. So Falun Gong practitioners rely largely on their own resources to respond to the persecution.

See also

literature

- David Ownby: Falun Gong and the Future of China. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-532905-6 .

- David A. Palmer: Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-231-14066-9 .

- Herman Salton, Arctic Host: Icy Visit: China and Falun Gong face off in Iceland. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8433-6513-0 .

- Kai-Ti Chou: Contemporary religious movements in Taiwan: rhetorics of persuasion . Edwin Mellen Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7734-5241-1 .

- Kenneth S. Cohen: The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing. Ballantine, New York 1999, ISBN 0-345-42109-4 .

- Kevin McDonald: Global Movements: Action and Culture. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-1613-8 .

- Nick Couldry, James Curran: Contesting Media Power. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD 2003, ISBN 978-0-7425-2385-2 . (Chapter 13, Yuezhi Zhao: Falun Gong, Identity, and the Struggle over Meaning Inside and Outside China . )

- Sharon Hom and Stacy Mosher: Challenging China: Struggle and Hope in an Era of Change. The New Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-59558-416-8 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n David Ownby, Falun Gong and the Future of China , Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 9780195329056 , accessed February 3, 2018

- ↑ a b James Tong, An Organizational Analysis of the Falun Gong: Structure, Communications, Financing , The China Quarterly, Volume 171, S: 636-660, September 1, 2002, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ List of languages , Falun Dafa.org, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b Noah Porter, Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study ( September 9, 2006 memento in the Internet Archive ), July 18, 2003, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Mickey Spiegel, Dangerous meditation: China's campaign against Falungong, Human Rights Watch , New York Washington London Brussels, January 2002, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ The crackdown on Falun Gong and other so-called "heretical organizations" ( July 2, 2010 memento on the Internet Archive ), Amnesty International, March 23, 2000, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b Ethan Gutmann, China's Gruesome Organ Harvest , The Weekly Standard, November 24, 2008, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ A b David Ownby, Falun Gong and the Future of China , Oxford University Press, May 27, 2010, p. 248, ISBN 978-0199738533 , accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ Adam Frank Falun Gong and the Thread of History , 2004, p. 241, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b c David Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science and Utopia in China , New York: Cambridge University Press, August 13, 2013, ISBN 9780231511704 , accessed August 29, 2017.

- ↑ Cheris Shun-ching Chan, The Falun Gong in China: A Sociological Perspective , The China Quarterly, 179, pp. 665-683, September 1, 2004, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Noah Porter, Professional Practitioners and Contact Persons Explicating Special Types of Falun Gong Practitioners , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 62-83, University of California Press, November 2, 2005, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c Susan Palmer and David Ownby, Falun Dafa Practitioners: A Preliminary Research Report , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 133-137, University of California Press, October 4, 2000, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Noah Porter, Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study ( September 9, 2006 memento in the Internet Archive ), July 18, 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Hu Ping, The Falun Gong Phenomenon , in Challenging China: Struggle and Hope in an Era of Change , Sharon Hom and Stacy Mosher, The New Press, p. 231, August 31, 2008, ISBN 978-1-59558-416- 8 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ David Ownby, Falungong and Canada's China Policy , International Journal, Spring 2001, p. 193. Quotation: These people have discovered what they consider the truth of the universe to be. They have freely and openly acknowledged this discovery, and if they change their minds they are free to go elsewhere and do something else. The Falun Gong community seems supportive but not restrictive, apart from the peer pressure that exists in many group situations. There is no visible power structure to chastise a misbehaving practitioner, nor do practitioners tell each other what to do or what to believe. accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ David Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science and Utopia in China , New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 241–246, ISBN 9780231511704 , 2007, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ A b Noah Porter, Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study ( September 9, 2006 memento on the Internet Archive ), University of South Florida, July 18, 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b Craig Burgdoff, How Falun Gong Practice Undermines Li Hongzhi's Totalistic Rhetoric , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 6, No. 2, University of California Press, April 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Kai-Ti Chou, Contemporary religious movements in Taiwan: rhetorics of persuasion , Edwin Mellen Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7734-5241-1 , accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ Kevin McDonald, Global Movements: Action and Culture, Wiley-Blackwell , March 3, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-1613-8 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ A b Mark R. Bell and Taylor C. Boas, Falun Gong and the Internet: Evangelism, Community, and Struggle for Survival , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 6, Issue 2, pp. 277-93 , ISSN 1092-6690, April 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Kai-Ti Chou, Contemporary religious movements in Taiwan: rhetorics of persuasion , Edwin Mellen Press, p. 141, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7734-5241-1 , accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c d e f Scott Lowe, Chinese and International Contexts for the Rise of Falun Gong , Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 263-276, University of California Press, April 2003, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Local Contacts , Falundafa.org, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Craig A. Burgdoff, How Falun Gong Practice Undermines Li Hongzhi's Totalistic Rhetoric , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 6, No. 2, University of California Press, pp. 332-347, April 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ A b David Ownby, The "Falun Gong" in the New World , European Journal of East Asian Studies, Brill, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 313-314, 2003, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ A b c David Ownby, In search of charisma — the Falun Gong diaspora , Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 106-120, University of California Press, November 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ Susan Palmer, David Ownby, Falun Dafa Practitioners: A Preliminary Research Report , Nova Religio, The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 134-135, University of California Press, October 4, 2000, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ David Ownby, Falun Gong and the Future of China , Oxford University Press, pp. 132-134, 2008, ISBN 9780195329056 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Annual Report 2009 ( Memento of November 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), Congressional Executive Commission on China, October 10, 2009, web archive , accessed on August 29, 2017

- ^ Direct Litigation , Human Rights Law Foundation, accessed February 3, 2018

- ↑ La Audiencia pide interrogar al ex presidente chino Jiang por genocidio , Elmundo, November 15, 2009, accessed on February 3, 2018

- ↑ Charlotte Cuthbertson, Spanish Judge Calls Top Chinese Officials to Account for Genocide , Epoch Times, November 15, 2009, accessed February 3, 2018

- ↑ Luis Andres Henao, Argentine judge asks China arrests over Falun Gong , Reuters, December 22, 2009, accessed February 3, 2018

- ↑ a b Terry Baynes, Suit claims Cisco helped China repress religious group , Reuters, May 20, 2011, accessed February 3, 2018

- ↑ Falungong row overshadows Australia's Chinese new year preparations , Channel News Asia, February 8, 2005, web archive, accessed on February 4, 2018

- ^ Zoe Corneli, Falun Gong Banned from Calif. New Year's Parades , NPR, February 10, 2006, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Clay Lucas, Falun Gong is So out at city hall , The Age, October 31, 2007, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Ottawa's Tulip Festival apologizes for barring Falun Gong band , CBCNews, Ottawa, May 14, 2008, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Tribunal Finds Falun Gong a Protected Creed under Ontario's Human Rights Code , Ontario Human Rights Commission, January 25, 2006, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Justice Department Resolves Discrimination Case Against Flushing, NY, Restaurant that Ejected Patrons Because of Religion , United States Department of Justice, August 12, 2010, accessed February 4, 2018

- ^ John Turley-Ewart, Falun Gong persecution spreads to Canada , The National Post, March 20, 2004, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Falun Gong: La Cour d'appel juge qu'il ya eu defamation , Droits Inc., May 26, 2008, accessed February 4, 2018

- ↑ Yuezhi Zhao, Falun Gong, Identity, and the Struggle over Meaning Inside and Outside China , in Nick Couldry, James Curran, Contesting Media Power: Alternative Media in a Networked World, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 209-223, ISBN 978 -0-7425-2385-2 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ About us , Epoch Times, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ About us , New Tang Dynasty Television, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Kathy Chen, Chinese Dissidents Take On Beijing Via Media Empire ( December 17, 2007 memento in the Internet Archive ), The Wall Street Journal, November 15, 2007, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Naoibh O'Connor, Falun Gong going for Guinness record ( January 6, 2005 memento on the Internet Archive ), The Vancouver Courier, August 5, 2004, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Mike Howell, Time to get tough on Falun Gong, says mayor ( October 19, 2006 memento in the Internet Archive ), The Vancouver Courier, June 7, 2006, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Falun Gong wins Vancouver Court Battle , CBCNews, October 19, 2010, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Falun Gong Protest Jiang Zemin's Visit to Germany , n-tv, April 8, 2002, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ David H. Ellis, Parade tension eases, as Falun Gong group is allowed to march ( Memento of the original from September 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , The Villager, Volume 74, Number 10, 7. – 13. July 2004, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ About the Company , Shen Yun Performing Arts, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Julie Ruff, Artist hopes to raise awareness ( Memento from February 23, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ), The Daily Texan, web archive , October 17, 2002, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ Rybev Wake, Persecuted artists show work , clearwisdom.net, May 17, 2001, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ^ Exhibition "The Art of Truthfulness-Compassion-Forbearance" , LebeArtMagazin, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Followers of Falun Gong open The Art of Zhen, Shan, Ren exhibition in CUC Liverpool ( Memento June 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Liverpool Daily Post, August 25, 2011, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ About the Performance , Shen Yun Performing Arts, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Shenyun 2012 Washington DC performance , Shen Yun Performing Arts, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Global Competition Series ( Memento June 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), New Tang Dynasty Television, web archive , accessed on February 8, 2018

- ^ Falun Dafa Information Center , accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ United Nations Reports , Falun Gong Human Rights Working Group, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ Mission Statement , World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ About us , Committee to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b Ethan Gutmann, Hacker Nation: China's Cyber Assault ( Memento of the original from December 24, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , World Affairs Journal, May / June 2010, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ Vince Beiser, Digital Weapons Help Dissidents Punch Holes in China's Great Firewall , Wired, November 1, 2010, accessed February 8, 2018

- ^ Eli Lake, Hacking the Regime: How the Falun Gong empowered the Iranian uprising , New Republic Magazine, September 3, 2009, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b Alanah May Eriksen, Human rights marchers want Olympic boycott , New Zealand Herald, December 17, 2007, david-kilgour.com, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ City rally hears student's tale of torture, imprisonment in China ( Memento November 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), The Calgary Herald, May 20, 2008, web archive , accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ Caylan Ford, Tradition and Dissent in China , Thesis to The George Washington University, May 15, 2011, accessed February 8, 2018

- ↑ a b c d Alex Newman, China's Growing Spy Threat , The Diplomat, September 19, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c Expressing the sense of Congress regarding oppression by the Government of the People's Republic of China of Falun Gong in the United States and in China , United States House of Representatives, House Concurrent Resolution 304, October 16, 2003, accessed October 29, 2003 August 2017

- ↑ Annual Report 2008 ( Memento of November 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), Congressional-Executive Commission on China, October 31, 2008, web archive , accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b Liu Li-jen, Falun Gong says spying charge is tip of the iceberg , Taipei Times, October 3, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c Sven Röbel and Holger Stark, A Chapter from the Cold War Reopens: Espionage Probe Casts Shadow on Ties with China , Spiegel Online International, June 30, 2010, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ Bill Gertz, Chinese spy who defects tells all , The Washington Times, March 19, 2009, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ Matthew Robertson and Tian Yu, Man Convicted of Spying on Falun Gong in Germany , Epoch Times, June 12, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Shi Shan, Asylum-Seeking Chinese Diplomat Says He Was Told To Harass Falun Gong Followers , RFA Radio Free Asia, June 24, 2005, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ China's Ministry of Public Security Issues Secret Directive to Investigate and Bar Thousands Worldwide from Olympics , Falun Dafa Information Center, May 30, 2007, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Anita Chang, Religious texts allowed at Beijing Olympics, but for personal use only; Falun Gong excluded ( memento of July 24, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), The Associated Press, November 8, 2007, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ China asks Japan for information on Falun Gong members ( June 2, 2016 memento in the Internet Archive ), Asian Political News, July 21, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ Herman Salton, Arctic Host, Icy Visit: China and Falun Gong face off in Iceland , LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010, ISBN 9783843365130 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Morgunbladid, Baðst afsökunar á Falun Gong-máli , May 27, 2011, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ^ Edmund Tadros, Qantas 'demoted me for being Falun Gong' , NewsComAu, September 1, 2010, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Hong Kong immigration admits blacklist , Associated Press, Taipei Times, May 23, 2001, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Min Lee, Canadian Falun Gong follower refused boarding onto Hong Kong-bound flight ( June 11, 2014 memento on the Internet Archive ), Associated Press, February 19, 2004, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ International Religious Freedom Report 2009 , US Department of State, October 26, 2009, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Taiwanese Human Rights Lawyer Denied Entry in Hong Kong, AFP, June 24, 2007

- ↑ Shelley Huang, Taiwanese Falun Gong criticize Hong Kong court ruling , Taipei Times, September 8, 2009, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Shelley Huang, Falun Gong criticize Hong Kong court ruling , Taipei Times, September 8, 2009, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Polly Hui, Falungong decries HK as democracy row deepens , Agence France Presse, January 27, 2010, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Sonya Bryskine, Kong Court upholds Freedom and Shen Yun , March 9, 2011, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b Steve Park, Officials ask US cities to snub sect , Washington Times, April 8, 2002, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Stephen Thorne, Chinese embassy officials beat me, student says ( September 30, 2007 memento in the Internet Archive ), The Star, WorldWide Religious News, January 4, 2002, web archive , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Baldwin Ndaba, "Falun Gong dissident shot in Joburg," Center for Studies on New Religions, June 30, 2004, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Iena Dua, Falun Dafa ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , The Argentina Independent, February 2, 2009, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ David Matas, China and Human Rights: A Global Strategy, Remarks prepared for delivery to the Cambridge Union , Cambridge University, United Kingdom, March 11, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ John Nania, A Strange Chinese Export ( Memento of the original from February 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Association for Asian Research, December 26, 2005, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Lisa L. Colangelo, Falun Gong supporters in Flushing say they're targets , New York Daily News, May 29, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Brad Hamilton, Diplo 'Gong' Buster: Chinese Consul 'Admits' Inciting NY Attacks , New York Post, September 14, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ A b John Turley-Ewart, Falun Gong persecution spreads to Canada , The National Post, March 20, 2004, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Ian Austen, Chinese Call Prompts CBC to Pull Show , The New York Times, November 9, 2007, accessed August 29, 2017

- ^ Peter Manseau, Falun Gong's March , Salon, June 28, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Claudia Rosett, Will Chinese Repression Play in Peoria? , The Wall Street Journal, February 21, 2002, clearwisdom.net, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Perry Link, The Anaconda in the Chandelier: Chinese censorship today ( Memento of the original from November 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Association for Asian Research, May 27, 2005, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c Ehtan Gutmann, Carrying a Torch for China , The Weekly Standard, April 21, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ European Satellite Operator Eutelsat Suppresses Independent Chinese-Language TV Station NTDTV to Satisfy Beijing , Reporters Without Border, July 10, 2008, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Freedom House condemns Prison Sentences for Vietnamese Broadcasters , Freedom House, November 10th 2011, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ Vietnam Falungong jailed over China broadcasts , Agence France Presse, November 11, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Radio Era Baru Forcibly Closed by Police , Reporters Without Borders, September 13, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Andrew Higgins, China Seeks to Silence Dissent Overseas , The Washington Post, August 5, 2011, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ David Ownby, Falun Gong and the Future of China , Oxford University Press, p. 229, 2008, ISBN 9780195329056 , accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Thomas Lum, CRS Report for Congress: China and Falun Gong ( Memento June 28, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), (PDF), Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, May 25, 2006, webarchiv, accessed August 29 2017

- ↑ United States House Resolution 605 , United States Government Printing Office, March 16, 2010, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Bruce Einhorn, Congress Challenges China on Falun Gong & Yuan, Business Week , March 17, 2010, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings, Civil and Political Rights, Including the Question of Disappearances and Summary Executions , January 11, 2001, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ Louis Charbonneau, UN envoy defends Falun Gong, "evil cult" for China , United Nations, Reuters, October 22, 2010, accessed on August 29, 2017

- ↑ Katrina Lantos Swett and Mary Ann Glendon, US should press China over Falun Gong , CNN, July 23, 2013, accessed August 29, 2017

- ↑ a b c Leeshai Lemish, Media and New Religious Movements: The Case of Falun Gong , A paper presented at The 2009 CESNUR Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, 11.-13. June 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2017

- ↑ Adam Frank Falun Gong and the Thread of History , 2004, 233-241, accessed August 29, 2017