Persecution of Falun Gong

The persecution of Falun Gong (also called Falun Dafa ) is based on the Chinese Communist Party's campaign , which began in 1999, to end the spiritual practice of Falun Gong in China . Persecution measures include an extensive propaganda campaign, a program of forced ideological conversion and re-education, and a variety of unlawful coercive measures, such as arbitrary arrests, forced labor and physical torture , often resulting in death.

Falun Gong is a qigong discipline that combines slow practice and meditation with a moral philosophy based on the principles of Truthfulness-Compassion-Forbearance. It was founded by Mr. Li Hongzhi and unveiled to the public in Changchun , Jilin Province in May 1992 . After a period of rapid growth in the 1990s, the Communist Party began a campaign on July 20, 1999 to "eradicate Falun Gong".

To start and carry out the persecution of Falun Gong, an extra-legal organization called the 610 Office was established. The authorities mobilized the state media machinery, judiciary, police, military, education, and families and employers against Falun Gong. The campaign was driven by large-scale propaganda through television, newspapers, radio and the Internet. There have been reports of systematic torture, illegal imprisonment, forced labor, organ harvesting, and abusive psychiatric interventions with the obvious aim of forcing practitioners to give up their belief in Falun Gong.

Foreign observers estimate that hundreds of thousands and perhaps millions of Falun Gong practitioners have been detained in labor camps for re-education through labor , prisons and other detention centers for refusing to give up the spiritual practice. Former prisoners reported that Falun Gong practitioners regularly received "the longest sentences and the worst treatment" in labor camps, and in some facilities, Falun Gong practitioners constitute the vast majority of prisoners. According to the New York Times , until 2009, within the Persecution campaign killed at least 2,000 Falun Gong practitioners. Some international observers and judicial authorities have described the campaign against Falun Gong as genocide . In 2009 courts in Spain and Argentina indicted high-ranking Chinese officials for their role in suppressing Falun Gong, genocide and crimes against humanity .

In 2006, allegations surfaced that large numbers of Falun Gong practitioners were killed to supply organs for China's organ transplant industry. An investigation by former Canadian Secretary of State and Public Prosecutor David Kilgour and Canadian human rights attorney David Matas both found in their investigation report that "the source of 41,500 organ transplants [in China] over the six-year period from 2000 to 2005 is unclear". This, along with over 50 other circumstantial evidence, led the two investigators to conclude that "large-scale organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners without their consent has occurred and is still happening." China analyst and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann estimates that 65,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs between 2000 and 2008. Between 2006 and 2008, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief Ms. Asma Jahangir repeatedly requested that “the Chinese government explain the allegation of the removal of vital organs from Falun Gong practitioners got to. It should also fully explain the source of the organs of the sudden surge in organ transplants that have been going on in China since 2000. ”But the Chinese government failed to provide a clear explanation. In August 2009, Manfred Nowak once again commented on this issue: “The Chinese government still has to become clean and transparent [...]. It is still not clear how the massive increase in organ transplants in Chinese hospitals since 1999 can be possible, even though there have never been so many volunteer donors. "

background

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a spiritual qigong practice that consists of physical exercises, meditation and a moral philosophy, and is linked to Buddhist traditions. The practice was first taught publicly in the spring of 1992 by Li Hongzhi in northeast China, towards the end of the Chinese "Qigong boom".

Falun Gong initially enjoyed significant public support in the early years of its development. It was sponsored by the state-run Qigong Association and other government agencies. However, from the mid-1990s onwards, the Chinese authorities tried to keep the influence of qigong practices in check and imposed stricter requirements on the various qigong denominations in the country. In 1995, the authorities ordered all qigong groups to establish branches of the Communist Party. The government also tried to formalize ties with Falun Gong and thus exercise greater control over the practice. However, Falun Gong resisted co-opting and instead filed an application to withdraw from the state qigong association entirely.

After the group severed ties with the state, they faced increased criticism and surveillance by the country's security apparatus and propaganda department. In July 1996, further publication of the Falun Gong books was banned and official news outlets began to criticize the group as a kind of " reactionary superstition" whose " theistic " orientation would conflict with official ideology and national agenda.

Tensions continued to escalate into the late 1990s. In 1999, polls showed that around 70 million people in China practiced Falun Gong. Although some government agencies and senior officials continued to express their support for the practice, others grew more suspicious of the size and capacity of an independent organization.

The Communist Party published an article in Science and Technology for the Young in April 1999, portraying Falun Gong as a superstition and a health hazard. As a result, several dozen Falun Gong practitioners went to the editorial office in Tianjin on April 22, 1999 to peacefully protest the content of the article, but were beaten and arrested by the police. Practitioners were told that the arrest warrant was from the Ministry of Public Security and that those arrested could only be released with the approval of the Beijing authorities.

As a result, on April 25, 1999, about 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners gathered peacefully near the Zhongnanhai government area in Beijing to demand the release of Tianjin practitioners and an end to the escalation of harassment against them. It was an effort by Falun Gong practitioners to seek redress from the political leaders by going to them and "quietly and politely explaining that they are not being treated so shabbily." This was the first Mass demonstration at the Zhongnanhai site in the history of the People's Republic of China and the largest protest in Beijing since 1989. Several representatives of Falun Gong spoke to then Prime Minister Zhu Rongji , who assured them that the government was not against Falun Gong and promised them, that the practitioners from Tianjin would be released. After that, the crowd broke up peacefully, apparently believing that their demonstration was a success.

Security Tsar and Politburo member Luo Gan , however, was less conciliatory and urged the then General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Jiang Zemin , to find a decisive solution to the "Falun Gong problem".

Nationwide persecution

On the night of April 25, 1999, then-General Secretary of the Communist Party, Jiang Zemin, issued a letter expressing his wish that he would see Falun Gong defeated. This letter caused concern among Communist Party members at the popularity of Falun Gong. Jiang reportedly called the Zhongnanhai protest "the worst political incident since the June 4, 1989 political disturbance ."

At a Politburo meeting on June 7, 1999, Jiang described Falun Gong as a grave threat to Communist Party's authority - "something unprecedented in the country since it was founded 50 years ago" - and ordered the establishment of a high-level committee to "fully prepare for the work of eliminating Falun Gong". Rumors of an impending raid spread across China, leading to demonstrations and petitions. The government publicly denied the reports, calling them "completely baseless" and assuring them that they never banned qigong activities.

Just after midnight on July 20, 1999, public security officers arrested hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners in their homes in cities across China. Estimates of the number of arrests vary from several hundred to over 5,600. A Hong Kong newspaper reported that 50,000 people were arrested in the first week of the raid. Four Falun Gong practitioners in Beijing were arrested and immediately tried on charges of "revealing state secrets". The Public Security Bureau ordered churches, temples, mosques, newspapers, media, courts, and the police to suppress Falun Gong. This was followed by massive demonstrations by practitioners in about thirty cities for three days. Protesters have been arrested and detained in sports stadiums in Beijing and other cities. Editorials in state newspapers urged people to give up Falun Gong, and members of the Communist Party in particular were reminded that they were atheists and should not allow themselves to "become superstitious by continuing to practice Falun Gong." Li Hongzhi responded with a statement on July 22, 1999:

“We are not against the government now, nor will we be in the future. Other people may treat us badly, but we do not treat others badly, nor do we treat people as enemies. We call on all governments, international organizations and people around the world who are of good will to give us their support and help to resolve the current crisis that is taking place in China. "

reasons

Foreign observers tried to explain the Communist Party's reasons for illegally banning Falun Gong and found a variety of factors. These include Falun Gong's popularity, its independence from the state, and its refusal to submit to the party line. Added to this are the internal power politics within the Communist Party itself and the moral and spiritual content of Falun Gong, which contradict the Marxist-Leninist atheist ideology.

A report in the World Journal , a Chinese newspaper in North America, indicated that certain high-ranking party officials had wanted to crack down on the practice for years but lacked sufficient pretexts before the protest took place at Zhongnanhai. A report says that part of the protest was initiated by Luo Gan, a longtime opponent of Falun Gong. Other reports wrote that there were cracks in the Politburo at the time of the incident. Willy Wo-Lap Lam of CNN wrote that Jiang's campaign against Falun Gong was probably used to prevent allegiance to promote themselves. Lam quoted a Party veteran as saying, "By starting a Mao-style campaign [against Falun Gong], Jiang has forced senior cadres to swear allegiance to his line." Jiang is persecuted by Falun Gong for the final decision personally responsible, and Washington Post sources citing, "Jiang Zemin alone decided that Falun Gong must be eliminated" and he "took up what he believed was an easy target." Christian Century's Dean Peerman cited reasons like presumably personal jealousy of Li Hongzhi. Saich posits the anger of the party leaders because of the widespread appeal and ideological struggle of Falun Gong. The Washington Post reported that members of the Politburo Standing Committee did not unanimously support the crackdown and that "Jiang Zemin alone decided that Falun Gong must be eliminated." The size and scope of Jiang's anti-Falun Gong campaign exceeded that of many previous mass movements.

Human Rights Watch said the crackdown on Falun Gong reflected historic efforts by the Chinese Communist Party to eradicate religions that the government believes are intrinsically subversive. Some journalists believe that Beijing's reaction reveals its authoritarian nature and intolerance in the "struggle for loyalty". The The Globe and Mail wrote: ". ... any group that is not under the control of the party, is a threat" In addition, the 1989 protests may have reinforced the fear of the political leadership that they could lose their power, which she lives in "mortal fear" of popular demonstrations. Craig Smith of the Wall Street Journal suggests that the government lacks moral credibility because it is fighting an explicitly spiritual enemy but, by definition, has no conception of spirituality. The party feels increasingly threatened by any belief system that challenges its ideology and has the ability to organize itself. According to China analyst Ethan Gutmann , the belief system of Falun Gong represents a revival of the traditional Chinese religion practiced by large numbers of Communist Party and military personnel. Therefore, Jiang Zemin found it particularly disturbing: “Jiang regards the threat to Falun Gong as ideological: spiritual beliefs against militant atheism and historical materialism. He wanted to rid the government and the military of such a belief. "

Legal and Political Mechanisms

610 Office

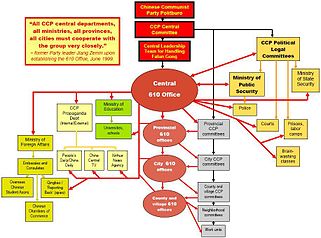

On June 10th, the party established the 610 Office , a Communist Party-run security service responsible for coordinating the elimination of Falun Gong. The office was not set up with any legislative measure that would describe its precise duties. Because of this, it is sometimes called an illegal organization. Nonetheless, according to Professor James Tong of UCLA ( University of California ) , his duties are "to coordinate central and local party and state authorities that have been asked to act in close coordination with this office". The 610 Office heads are "able to attract top government and party officials ... and access their institutional resources," and have personal access to the Communist Party general secretary and the prime minister.

The office is headed by a senior member of the Communist Party Politburo or the Politburo Standing Committee. It is closely related to the powerful Political and Legal Committee of the Communist Party of China. Soon after the establishment of the Central 610 Office, local branches were established at every administrative level wherever there were Falun Gong practitioners in the population, including provincial, county, municipal, and sometimes even neighborhood levels. In some cases, 610 Offices have even been established in large corporations and universities.

According to reports, 610 Office personnel from other departments or state agencies (such as the Political and Legal Committee and the Public Security Bureau) were used. Hao Fengjun, a former employee of the Tianjin City 610 Office, was one such officer who was forcibly transferred. Prior to his transfer, he worked for the Tianjin Public Security Bureau. According to Hao, although some officers volunteered for posts in the 610 Office, the selection was usually random.

The main functions of the 610 Office include coordinating anti-Falun Gong propaganda, monitoring and collecting information, and punishing and "transforming" Falun Gong practitioners. The office is reportedly involved in extrajudicial convictions, forced relocation, torture, and sometimes the killing of Falun Gong practitioners.

In addition to its in-country functions to persecute Falun Gong, the 610 Office was also used for overseas intelligence activities. After Hao Fengjun defected and defected while on a trip to Australia, he reported in Melbourne, Australia in June 2005 that his role in the 610 Office consisted of collecting and analyzing intelligence reports on foreign Falun Gong populations, including in the United States, Canada and Australia. Hao added that the intelligence agency's spy network consists of three tiers: first, professional agents who come from the police academy and are paid to travel abroad; secondly, from “work colleagues” who appear as business people and are attached to foreign companies; and thirdly, “friends” who infiltrate foreign countries and “befriend” the Chinese and Westerners. All three levels work on monitoring Falun Gong, among other things. At an International Society for Human Rights (ISHR) press conference in October 2005, Hao released further details about his role in the 610 Office: "As part of my work for the 610 Office ... I learned that the office that originally dealt only with Falun Gong , had received an order extension. In addition to Falun Gong and other Qi groups, 610 now persecutes a total of 14 religious groups, including the Protestant house churches and Catholics who are loyal to Rome. "

Journalist Ian Johnson , who won a Pulitzer Prize for reporting the crackdown on Falun Gong , wrote that the 610 Office's mission was to “mobilize the country's indulgent social organizations. Under orders from the Public Security Bureau, churches, temples, mosques, newspapers, media, courts, and police swiftly sided with the government's simple plan: to crush Falun Gong; no measures are too excessive. "

Prominent human rights attorney Gao Zhisheng wrote in an open letter to the Chinese leadership in 2005 that officials from the 610 Office beat and sexually harassed Falun Gong practitioners: "Of all the true reports of incredible violence I have ever heard of; Of all the records of inhuman torture by the government on their own people, what shakes me most is the common practice that the 610 Office and police have assaulted female genitals. ”Hao Fengjun described how one of his colleagues in the office said 610 hit an elderly Falun Gong practitioner with an iron bar. This event helped Hao in his decision to leave for Australia. The 2009 UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings reported allegations that the 610 Office was involved in the torture deaths of Falun Gong practitioners in Beijing prior to the 2008 Olympics.

Official documents and circulars

Beginning in July 1999, the Chinese authorities issued a series of notices and circulars describing measures to be taken against Falun Gong and restrictions on practicing and expressing religious beliefs.

- On July 22nd, 1999, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued a circular stating that the Falun Dafa Research Association was an unregistered (and therefore illegal) organization.

- On July 22nd, 1999, the Ministry of Public Security issued a circular banning the practice or spreading of Falun Gong and forbidding any attempt to petition or oppose the government's decision.

- In July 1999, the Ministry of Human Resources issued a circular stating that all government employees were prohibited from practicing Falun Gong. Subsequent documents instructed local authorities "how to deal with officials who have practiced Falun Gong."

- On July 26th, 1999, the Ministry of Public Security requested the confiscation and destruction of all Falun Gong-related literature. The Falun Gong books were then shredded, burned, and bulldozed in front of television cameras. Millions of publications have been destroyed, shredded, shredded, or burned for television cameras.

- On July 29, 1999, the Beijing Judicial Bureau issued a notice prohibiting lawyers from defending Falun Gong practitioners. The Justice Department also issued instructions that lawyers cannot represent Falun Gong without permission.

- On October 30, 1999, the National People's Congress amended a law (Article 300 of the Penal Code) to suppress "heterodox religions" across China. This legislation was used to retrospectively legitimize the persecution of spiritual groups considered "dangerous to the state". This change in the law banned large public gatherings as well as religious and qigong organizations that organize themselves across several provinces or cooperate with groups abroad. The decision of the National People's Congress mentioned, "All corners of society should be mobilized to prevent and combat the activities of heretical organizations, and a comprehensive administrative system must be put in place." On the same day, the Supreme People's Court issued a judicial interpretation , which orders measures to punish those who violate this law.

- On November 5, 1999, the Supreme People's Court issued a notice instructing the local courts on how to handle cases of indicting people for "using or organizing heretical organizations, particularly Falun Gong." It called for Falun Gong practitioners to be prosecuted for crimes that include "inciting activities" to "divide China, endanger national unity, or undermine the socialist system."

Human rights experts and legal monitors found that the official guidelines and legal documents for this purge fell short of international legal norms and violated provisions in China's own constitution.

Impact on the rule of law

The Justice Department required attorneys to obtain permission first before accepting cases of Falun Gong and asked them to "interpret the law in a manner that is consistent with the spirit of government regulations." In addition, the Supreme People's Court issued a notice to all the lower courts stating that it was their "political duty" to "impose severely severe sentences" on groups considered heretical, particularly Falun Gong. It required courts at all levels to handle Falun Gong cases according to the instructions of the Communist Party Committee, which ensures that Falun Gong cases are judged on political grounds rather than evidence. Brian Edelman and James Richardson of the University of California wrote that the Supreme Court's advice "does not go well with a defendant's fundamental right to defense" and that it appears to assume "that a person is guilty before a trial" .

According to Ian Dobinson, the Communist Party's campaign against Falun Gong was a turning point in the development of the Chinese judicial system that marked a "significant step backwards" in the development of the rule of law. The legal system became increasingly professional in the 1990s, and a series of reforms in 1996-97 reaffirmed the principle that all penalties must be based on the rule of law. However, the campaign against Falun Gong would not have been possible if it had been carried out within the narrow limits of existing Chinese criminal law. To persecute this group, the judicial system fell back in 1999 and was used as a political tool. The laws were then applied flexibly to advance the Communist Party's political goals. Edelman and Richardson write, “The Party's and government's response to the Falun Gong movement violates citizens' rights to a judicial defense and freedom of religion, expression and assembly enshrined in the Constitution ... the Party will do whatever it takes to destroy any perceived threat to its supreme control. This represents a passing of the rule of law and goes in the direction of the historical Mao policy of 'sole rule'. "

propaganda

Start of the campaign

One of the most important elements of the anti-Falun Gong campaign was a propaganda campaign to discredit and demonize Falun Gong and its teachings.

Within the first month of the raid, major state newspapers saw 300 to 400 articles attacking Falun Gong, while prime-time television coverage of alleged revelations about the group was carried out without different views in the media. The propaganda campaign focused on claims that Falun Gong endangers social stability, is deceptive and dangerous, is "anti-science" and threatens progress, and argued that Falun Gong's moral philosophy is inconsistent with Marxist social ethics.

For several months, CCTV's evening news was almost entirely anti-Falun Gong rhetoric. China scholars Daniel Wright and Joseph Fewsmith described this as "a study of total demonization". Beijing Daily compared Falun Gong to "a rat that crosses the street and everyone yells at to crush it." Others said that there would be a "long-term, complex, and grave" struggle to "eradicate" Falun Gong.

State propaganda first used the appeal of scientific rationalism to argue that the worldview of Falun Gong was "in complete contradiction to science" and communism. For example, on July 27, 1999, the People's Daily claimed that the fight against Falun Gong was "a fight between theism and atheism, superstition and science, idealism and materialism." Additional editorials stated that Falun Gong's "idealism and theism are absolutely at odds with the basic theories and principles of Marxism" and that the "principles of Truth, Kindness and Forbearance that [Falun Gong] preach have nothing to do with socialist ethical and cultural progress." have in common that we strive for and want to achieve ”. The suppression of Falun Gong has been portrayed as a necessary step to maintain the Communist Party's "leading role" in Chinese society.

In the early stages of the fight, the evening news broadcast pictures of large piles of Falun Gong materials being crushed or burned. On July 30th, 10 days after the persecution began, Xinhua reported the confiscation of over a million Falun Gong books and other materials; Hundreds of thousands were burned and destroyed.

The official propaganda against Falun Gong continued and worsened in the months after July 1999. The rhetoric was broadened to claim that Falun Gong interacted with foreign "anti-China" forces. Media reports portrayed Falun Gong as harm to society, an "abnormal" religious activity and a dangerous form of "superstition" that would lead to madness, death and suicide. These reports were broadcast through all state and many non-state media channels, but also through work units and the Communist Party's own cell structure, which permeates society.

Harvard historian Elizabeth Perry writes that the basic pattern of the offensive was similar to the "anti-right campaign of the 1950s [and] the campaign against intellectual pollution of the 1980s". As in the time of the Cultural Revolution , the Communist Party held rallies in the streets and held "stop working" meetings in remote western provinces through government agencies such as the Meteorological Bureau to blacken the practice. Local authorities ran "study and training programs" across China, and official cadres went to villagers and farmers' homes to explain to them "in simple terms the harm that Falun Gong does to them."

Use of the term "cult"

Despite the party's efforts to generate widespread popular support for the persecution of the group, the initial allegations against Falun Gong failed. In October 1999, three months after the persecution began, the Supreme People's Court issued a legal interpretation classifying Falun Gong as "xiejiao". A direct translation of the word is "heretical doctrine," but it was portrayed as an evil cult in English during the anti-Falun Gong propaganda campaign . In connection with Imperial China, the term "xiejiao" was used to refer to non-Confucian religions. However, in the context of communist China, it is used to target religious organizations that do not submit to the authority of the communist party. Julia Ching writes that the term "malevolent cult" was defined by an atheist government "for political premises, and not by any religious authority," and is used by the authorities to make previous arrests and detentions constitutional.

Ian Johnson argued that by using the term "cult" the government put Falun Gong on the defensive; she "camouflaged [her] fight with the legitimacy of the anti-cult movement of the West". Historian David Ownby wrote similarly, saying, "The entire subject of the supposed cultic nature of Falun Gong has been misled from the start, cleverly exploited by the Chinese state to dull the appeal of Falun Gong." According to John Powers and Meg YM Lee, the government did not see it as a threat prior to the persecution because Falun Gong was popularly classified as an "apolitical qigong practice club". Therefore, the most critical strategy in the persecution campaign against Falun Gong was to convince people to rearrange Falun Gong under a series of "negatively charged religious labels" such as "evil cult," "sect," or "superstition". In this process of renaming, the government tried to use for itself "the deep reservoir of negative feelings" which are connected with the historical role of the quasi-religious cults as destabilizing forces in the political history of China.

Chinese overseas propaganda using this term has been censored by Western governments. In 2006, the Canadian Radio-TV-Telecommunications Commission disapproved of the anti-Falun Gong broadcasts on Chinese Central Television (CCTV), stating, "These are expressions of extreme malice against Falun Gong and its founder, Li Hongzhi. The ridicule, hostility, and abuse encouraged by these remarks could cause hatred or contempt against the target audience or individuals, and ... could incite violence and threaten the physical safety of Falun Gong practitioners. "

Self-immolation incident in Tian'anmen Square

On January 23, 2001, there was a turning point in the government's campaign against Falun Gong when five people set themselves on fire in Tian'anmen Square . Chinese government sources immediately stated that it was Falun Gong practitioners who had been driven to suicide by the practice, and filled the nation's media with graphic images and fresh denunciations of the practice. The self-immolation was presented as evidence of how "dangerous" Falun Gong was and was used to legitimize the government's fight against the group.

Falun Gong sources have contested the government's account of the truth, pointing out that its teachings specifically prohibit violence or suicide . Several Western journalists and scholars found inconsistencies in the official account of the events. This led many to believe that the so-called self-immolation might have been staged to discredit Falun Gong. The government did not allow independent investigations and denied access to the victims by Western journalists and human rights groups. However, two weeks after the self-immolation incident, the Washington Post published an investigation into the identities of two victims and found that "no one had ever seen [these two] practice Falun Gong."

The state propaganda campaign that followed the event undermined public sympathy for Falun Gong. Previously, as reported in Time magazine , many Chinese believed that Falun Gong was not a real threat and that the crackdown by the state against them had gone too far. However, after the self-immolation incident, the media campaign against the group gained considerable ground. Posters, brochures, and videos were made detailing the alleged harmful effects of the Falun Gong practice, and anti-Falun Gong classes were regularly held in schools. CNN compared the Chinese government's propaganda initiative to past political movements such as the Korean War and the Cultural Revolution . Later, when public opinion turned against the group, the Chinese authorities began sanctioning the "systematic use of force" to eradicate Falun Gong. In the year after the incident, the arrests, torture and deaths of Falun Gong practitioners who were in custody increased significantly.

censorship

Interference with foreign correspondents

The Foreign Correspondents Association in China complained that its members were "persecuted, arrested, interrogated, and threatened" for reporting on the fight against Falun Gong. Foreign journalists who reported on a clandestine Falun Gong press conference in October 1999 were accused by Chinese authorities of "illegal reporting". Journalists from Reuters , the New York Times , the Associated Press and a number of other media organizations were interrogated by police, their employment and residence papers were temporarily confiscated, and they were forced to sign confessions. Correspondents complained that television satellite transmissions were also disturbed while they were being channeled through the CCTV transmitter. Amnesty International reported: "Several people have been sentenced to prison terms or long-term administrative detention for reporting the suppression or providing information on the Internet."

In 2002, Reporters Without Borders reported on China. Her report mentioned that foreign media photographers and cameramen were prevented from working in and around Tiananmen Square, where hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners have demonstrated in recent years. It is estimated that “at least 50 international press representatives have been arrested since July 1999 and some of them have been beaten by the police. Several Falun Gong practitioners were detained for speaking to foreign journalists ”. Ian Johnson, a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal in Beijing, wrote several articles about the persecution for which he was awarded the 2001 Pulitzer Prize . After receiving the Pulitzer, Johnson had to leave Beijing because "the Chinese police would have made my life in Beijing impossible".

Even entire news organizations are not immune to restrictions on press freedom when it comes to Falun Gong. In March 2001, Time Asia reported a story about Falun Gong in Hong Kong . As a result, the magazine was taken off the shelves in China and the owner threatened that his magazine would never be sold in the country again. In 2002, Western coverage of the persecution in China was completely stopped; at a time when the number of deaths of Falun Gong practitioners in custody was on the rise.

Internet censorship

Terms related to Falun Gong are the most heavily censored topics on the Chinese Internet and those who download or distribute information about Falun Gong run the risk of arrest.

Chinese authorities began filtering and blocking foreign websites as early as the mid-1990s. In 1998, the Ministry of Public Security developed plans for the Golden Shield Project to monitor and control online communications. The 1999 campaign against Falun Gong gave the authorities additional incentives to develop stricter censorship and surveillance techniques. The government also criminalized various forms of online contact. China's first integrated Internet content regime was approved in 2000. This made it illegal to disseminate information that "undermines social stability," "harms the honor and interests of the state," "undermines state policy on religions," or preaches "reactionary" beliefs, a veiled reference to Falun Gong was.

In the same year, the Chinese government looked for Western corporations to develop surveillance and censorship tools that would enable it to follow the trail of Falun Gong practitioners and block access to news and information on the subject in would be able to. North American companies such as Cisco Systems and Nortel marketed their services to the Chinese government by promoting their effectiveness in catching Falun Gong.

In addition to censoring the Internet within China's borders, the Chinese government and military are using cyber warfare to attack Falun Gong websites in the United States, Australia, Canada and Europe. According to Ethan Gutmann, a China analyst who researched the Chinese Internet, the first sustained denial of service attack by China was against foreign Falun Gong websites.

In 2005, Harvard and Cambridge researchers found that terms related to Falun Gong were censored most intensely on the Chinese Internet. Other studies of Chinese censorship and surveillance practices came to similar conclusions. A 2012 study that checked censorship rates on Chinese social media websites found that Falun Gong-related terms were among the most severely censored. Among the top 20 words that were most likely to be deleted from Chinese social media websites were three variations of the word "Falun Gong" and "Falun Dafa" respectively.

In response to Chinese Internet censorship, Falun Gong practitioners in North America developed a number of software tools, such as Ultrasurf , that could be used to bypass Internet censorship and surveillance.

Torture and Unlawful Killing

Re-education

An important part of the Chinese Communist Party's campaign is the re-education or "conversion" of Falun Gong practitioners. The transformation is described as "a process of ideological reprogramming in which practitioners are subjected to various methods of physical and psychological coercion until they renounce their belief in Falun Gong."

The conversion process usually takes place in prisons, labor camps, re-education facilities, and other detention centers. In 2001, the Chinese authorities ordered that no Falun Gong practitioner should be spared the coercive measures used to make them give up their belief. The most active Falun Gong practitioners were sent straight to labor camps "where they will first be 'broken' by beatings and other torture methods." Former prisoners said they were told by the guards that "no measure is excessive" to elicit waivers, and practitioners who refused to renounce Falun Gong were sometimes killed while in detention.

The conversion will be considered successful if Falun Gong practitioners sign five documents: a "guarantee" to stop practicing Falun Gong; a promise to sever all ties to the practice; two self-criticism documents in which they were critical of their own behavior and way of thinking; and criticizing the Falun Gong teachings. To demonstrate the righteousness of their renunciation, practitioners are forced to slander Falun Gong in front of an audience or on video. These recordings are then used by the state media as part of a propaganda mission. In some camps, the newly converted are required to participate in the transformation of other practitioners; among other things, they have to physically abuse other practitioners as evidence that they have completely given up the teachings of Falun Gong.

A report on the conversion process was published by the Washington Post in 2001 :

“At a police station in western Beijing, Ouyang was stripped and interrogated for five hours. "When I responded incorrectly, that is if I do not 'yes' said they have me with a stun gun abused," he said.

He was then sent to a labor camp in the western suburbs of Beijing. There, the guards forced him to stand facing the wall. If he moved, he would be electrocuted again. When he fell from tiredness, they electrified him again.

Each morning he only had five minutes to eat and go to the bathroom. "If I didn't make it, it would go in my pants," he said. "And that's why they shocked me."

On the sixth day, Ouyang said, he could no longer see properly because he had to stare at the plaster on the wall, which was only three inches from his face. His knees buckled, resulting in more beats and electric shocks. He gave in to the guards' demands.

For the next three days, Ouyang declared that he was giving up the Falun Gong teachings and shouted it against the wall. Officials kept electrifying his body, and he regularly polluted himself. Finally, on day 10, Ouyang's rejection of the group was deemed sufficiently righteous.

He was brought in front of a group of Falun Gong inmates and again rejected the group while a video camera recorded everything. Ouyang was taken out of prison and into brainwashing sessions. Twenty days later, after debating Falun Gong for 16 hours a day, he "passed".

“The pressure on me was and is incredible,” he said. “In the past two years, I've seen the worst that a person can do. We are really the worst animals on earth. ""

The methods of re-education are issued through incentives and guidelines from the central communist party authorities through the 610 Office. The local governments and detention center officials set quotas for the number of Falun Gong practitioners who must be successfully transformed. Fulfilling these quotas is rewarded with promotions and financial compensation. Officials who have achieved the goals set by the government receive “generous bonuses”. On the other hand, there are downgrades for those who haven't reached their quota. The central 610 Office periodically launches new education campaigns to revise the quotas and to establish and disseminate new methods. In 2010, it launched a widespread three-year campaign to reform large numbers of Falun Gong practitioners. Documents posted on party and local government websites pointed to specific re-education goals and set limits to acceptable "relapse rates". A similar three-year campaign was launched in 2013.

Torture and ill-treatment in custody

In order to achieve its re-education goals, the government sanctioned the systematic use of torture and violence against Falun Gong practitioners, including beating them with electric batons and giving them electric shocks. Amnesty International writes: "Detainees who do not cooperate with the process of re-education are subjected to torture and other ill-treatment ... with increasing severity." "Soft" methods include sleep deprivation, threatening family members, and denial of access to sanitation or toilets. The abuse escalates to beatings, 24-hour surveillance, solitary confinement, being shocked with electric batons, force-feeding, the "racket" and "tiger bench" torture with the person tied to a board with their legs bent backwards.

Since 2000, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture has documented 314 cases of torture in China that were carried out on over 1,160 people. Falun Gong accounted for 66% of the reported torture cases. The Special Rapporteur described the allegations of torture as "harrowing" and called on the Chinese government to "take immediate action to protect the life and integrity of its prisoners, in accordance with minimum standards for the treatment of prisoners."

A variety of torture methods are used, including electric shocks , hanging by the arms, handcuffing in painful positions, sleep and food deprivation, force-feeding, and sexual abuse - all of which have many variations.

Unlawful Killing

The Falun Dafa Information Center reports that over 4020 confirmed Falun Gong practitioners have died from torture and abuse in detention; usually after refusing to give up their belief. Amnesty International found that this number is "only a small fraction of the actual number of deaths, as many families do not seek legal redress for these deaths or systematically inform sources abroad". The majority of reported deaths occurred in China's northeastern provinces, Sichuan Province and areas around Beijing.

Among the first torture deaths reported in the Western press was that of Chen Zixiu, a retired factory worker from Shandong Province . In his Pulitzer Prize-winning article on the persecution of Falun Gong, Ian Johnson reports that labor camp guards shocked Ms. Chen with drovers in an attempt to force her to give up Falun Gong. Johnson wrote, “Officials forced Ms. Chen to walk barefoot in the snow. Two days of torture left her legs bruised, and her short black hair was matted with pus and blood ... She crawled outside, vomited, and collapsed. She never regained consciousness. ”Chen died on February 21, 2000.

On June 16, 2005, 37-year-old Gao Rongrong, an accountant from Liaoning Province, was tortured to death in custody. Two years before her death, Ms. Gao was detained in Longshan Forced Labor Camp, where she was shocked with electric batons and severely disfigured. Gao escaped the labor camp by jumping out of a window on the second floor. However, after pictures of her burned face were published, she was again targeted by the authorities trying to recapture her. She was arrested on March 6, 2005 and killed just three months later.

On January 26th, 2008, Beijing security officers stopped popular folk musician Yu Zhou and his wife Xu Na when they were on their way home from a concert. Ms. Yu Zhou, 42, was taken into custody. The authorities tried to force him to give up Falun Gong. He was tortured to death within 11 days.

Amnesty International reported testimony from tortured Falun Gong practitioners who were told under torture that the forced labor camp has a monthly allowable death rate for Falun Gong practitioners. The camp administration then described such deaths as suicide, illness, or accidents.

Organ harvesting

Main article: Organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners in China

In 2006, allegations were made that large numbers of Falun Gong practitioners were killed to supply organs to China's organ transplant industry. These allegations prompted former Canadian Secretary of State and Attorney General David Kilgour and Canadian human rights attorney David Matas to conduct an independent investigation. In July 2006, the Kilgour Matas Investigation Report came out. Kilgour and Matas had compiled over 50 circumstantial evidence and found, among other things, that "the source of the 41,500 transplants for the six-year period from 2000 to 2005 is unclear". Both concluded that "the Chinese government and its authorities in many parts of the country, particularly in hospitals, but also in detention centers and" people's courts ", have seen large but unknown numbers of Falun Gong prisoners of faith since 1999 Let death come ”.

The Kilgour-Matas investigative report draws attention to the extremely short waiting times for organs in China - one to two weeks for a liver versus 32.5 months in Canada - suggesting that organs can be procured on demand. A significant increase in the number of annual organ transplants in China began in 1999, coinciding with the start of the persecution of Falun Gong. China has few voluntary organ donors, but still carries out the second highest number of transplants per year. Kilgour and Matas also presented incriminating material from Chinese transplant center websites. These advertised the immediate availability of organs from living donors, including the prices for the organs. Kligour and Matas also publish transcripts of telephone interviews with doctors who confirmed that patients could receive organs from Falun Gong practitioners. An updated version of their report was published as a book in 2009.

Human rights activist Harry Wu told AsiaNews that organs are safely harvested from prisoners in China, but questioned the dimensions published in the investigation report. Canadian human rights attorney David Matas replied to Wu that his views indicated in his July 2006 article that he had already formed his mind in a letter dated March 21, 2006, two months before his own investigation was closed. As a result, these views were not based on his own full investigation. Harry Wu also characterized the volume of organ removal that Annie had described (2000 corneal removals in two years) as "technically impossible", but according to medical experts it is technically possible, since the removal of an eye cornea only takes 20 minutes and so a single surgeon could remove 2,000 corneas in 83 days.

In December 2005, China's Deputy Health Minister Huang Jiefu confirmed that the practice of harvesting organs from executed prisoners for transplants was widespread. In July 2006, Chinese officials denied the organ harvesting allegations and insisted that China followed the World Health Organization's principles that prohibit the sale of human organs without the donors' written consent. In November 2006, Huang Jiefu repeated his statement from December 2005 that the organs used by executed prisoners were being used.

In December 2006, the two major organ transplant centers in Queensland , Australia, stopped training Chinese surgeons after failing to receive assurances from the Chinese government about allegations of organ harvesting from Chinese prisoners, and banned joint organ transplant research programs with China. In April 2007, Chinese officials again denied allegations that prisoners were harvesting organs.

In May 2008, two UN Special Rapporteurs reiterated their requests to the Chinese authorities to respond appropriately to the allegations and provide a source for the organs that would explain the sudden surge in organ transplants in China since 2000. In an interview with The Epoch Times in 2009, Manfred Nowak , the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, said, “The Chinese government has not yet told the truth and is not transparent ... It remains to be seen how it can be possible that organ transplant operations in Chinese hospitals have increased massively since 1999, while there have never been so many volunteer donors available. ”Nowak submitted two reports to the UN Human Rights Council demanding that the Chinese government respond to the allegations. One report mentions that Falun Gong practitioners were killed during or immediately after organ harvesting operations. Nowak said, “The majority of the inmates in the (forced labor) camps were Falun Gong members. And that's so terrifying because none of these people had ever seen a trial. You have never been charged. "

In 2014, China analyst and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann published the results of his own investigation. Gutmann conducted extensive interviews with former inmates in Chinese labor camps and prisons, as well as former security guards and medical professionals who knew about organ transplant practices in China. He reported that organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience likely began in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in the 1990s and then spread across the country. Gutmann estimates that around 64,000 Falun Gong prisoners were killed for their organs between 2000 and 2008.

On June 22, 2016, David Kilgour, David Matas and Ethan Gutmann published the jointly prepared investigation report " Bloody Harvest / The Slaughter - An Update ". The 680-page report provides forensic analysis from over 2,300 sources, including publicly available figures from Chinese hospitals, interviews with doctors claiming to have performed thousands of transplants; Media reports, public statements, medical journals and publicly available databases. According to the investigation report, between 60,000 and 100,000 organ transplants have been performed annually at 712 liver and kidney transplant centers across China since 2000 to 2016, so that to date almost 1.5 million organ transplants have been performed without China having a functioning organ donation system. The report finds that the number of organ transplants in China is far higher than the Chinese government said; the organ sources for this high number of organ transplants come from killed innocent Uyghurs, Tibetans, domestic Christians, and mainly Falun Gong practitioners; and organ harvesting is a crime in China involving the Communist Party, state institutions, the health system, hospitals and transplant doctors.

Arbitrary arrests and detention

Foreign observers estimate that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Falun Gong practitioners are being illegally detained in forced labor camps (re-education through labor), prisons and other detention facilities.

Large-scale arrests are carried out at regular intervals and often coincide with important anniversaries or major events. The first wave of arrests came on the evening of July 20th when several thousand practitioners were removed from their homes and taken into police custody. In November 1999, four months after the campaign began, Vice Premier Li Lanqing announced that 35,000 Falun Gong practitioners had been arrested and arrested. The Washington Post wrote that "the number of people arrested ... in the operation against Falun Gong dwarfs any political campaign that has taken place in China in recent years." By April 2000, over 30,000 people had been arrested for defending Falun Gong and protesting in Tiananmen Square. On January 1st, 2001, seven hundred Falun Gong practitioners were arrested while demonstrating in Tian'anmen Square .

In the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, more than 8,000 Falun Gong practitioners were removed from their homes and workplaces in provinces across China. Two years later, authorities in Shanghai arrested more than 100 practitioners before the 2010 World's Fair. Those who refused to give up Falun Gong were tortured and taken to labor transforming institutions .

Re-education through work

From 1999 to 2013, the vast majority of detained Falun Gong practitioners were held in labor re-education through labor camps, an administrative detention system that allows people to be detained for up to four years without trial.

The "re-education through work" system was introduced during the Maoist era to punish and reprogram "reactionaries" and others who were viewed as enemies of the communist cause. In recent years it has been used to imprison petty criminals, drug addicts and prostitutes, as well as supplicants and dissidents. Judgments for re-education through labor can be arbitrarily extended by the police, and outside access is prohibited. Prisoners are forced to do heavy labor in mines, brick factories, agricultural fields, and many different types of factories. According to former prisoners and human rights organizations, physical torture, beatings, interrogations and other human rights violations take place in the camps.

China's network of re-education facilities expanded significantly after 1999 to accommodate the influx of Falun Gong inmates as authorities use the camps in an attempt to "re-educate" Falun Gong practitioners. Amnesty International reports that the "transformation through work" system plays an important role in the anti-Falun Gong campaign and has taken in large numbers of practitioners over the years. Evidence suggests that Falun Gong makes up an average of a third, and in some cases 100 percent, of the total inmates of certain re-education camps.

International observers estimated that Falun Gong practitioners constitute at least half of the total population in labor transformation camps , which equates to several hundred thousand people. Human Rights Watch's human rights monitors released a report in 2005 that mentions that Falun Gong practitioners constitute the majority of the detained population in the camps investigated. They received "the longest sentences and were treated the worst. The government's campaign against this group was so thorough that even longtime Chinese activists were afraid to say the group's name out loud. "

In 2012 and early 2013, public attention focused on a series of news and revelations about human rights violations at Masanjia Women's Forced Labor Camp , where about half of the inmates were Falun Gong practitioners. The revelations helped wake people up, and voices rose to end the "transformation through work" system. In early 2013, Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping announced that the labor re-education system would be abolished, which should result in the camps being closed. However, human rights groups found that many labor re-education facilities were simply renamed prisons or rehabilitation centers, and the use of extrajudicial detention for dissidents and Falun Gong practitioners continued.

The "re-education through work" system is often called Laogai , short for Láodòng Gaizào (???? / ????), which means "reform through work", and is actually a slogan of the Chinese criminal justice system.

Black prisons and re-education facilities

In addition to the prisons and labor transformation facilities , the 610 Office established a nationwide network of extrajudicial transformation centers to "transform the minds of Falun Gong practitioners." The facilities are operated out of court and the government officially denies their existence. They are known as " black prisons ," "brainwashing centers," "transformation through re-education centers," or "legal education centers," among others . Some are temporary programs that are set up in schools, hotels, on military grounds, or in work units. Others are permanent establishments operated as private prisons.

If Falun Gong practitioners in prisons or labor re-education camps refuse to be "re-educated", they can be sent directly to re-education facilities after their term ends. The US Congress Executive Committee on China writes that the facilities "are specifically used to detain Falun Gong practitioners who have completed their terms in the labor re-education camps but are not released by the authorities." Practitioners who are forcibly detained in the transformation centers have to pay tuition fees of hundreds of euros. The fees are extorted from family members as well as practitioners' employers and work units.

While officials in Beijing described the re-education process as "benign", those detained in the facilities described it as "extremely severe" mental and physical abuse. Journalist Ian Johnson writes that "murders have occurred in these unofficial prisons".

The government began using these "brainwashing sessions" in 1999, but the network of re-education facilities was not expanded nationwide until January 2001 when the central 610 Office ordered all government agencies, work units, and businesses to use them. The Washington Post reported, “People on the neighborhood committee also forced the elderly, the disabled, and the sick to attend these meetings. University authorities sent staff out to find students who had been expelled for practicing Falun Gong or who had dropped out of college to bring them back to the sessions. Other adherents were forced to leave sick relatives behind to attend the re-education sessions. ”After the official abolition of the“ re-education through labor ”system in 2013, the authorities relied more on re-education institutions to arrest and arrest Falun Gong practitioners imprison. After the camp for forced labor in Nanchong in the province of Sichuan had been closed, a dozen were at least practitioners of Falun Gong brought the detained there directly to a local re-education institution. Some former labor re-education camps have simply been renamed and converted into re-education facilities.

Psychiatric abuse

Falun Gong practitioners who refuse to give up their belief are sometimes forcibly taken to mental hospitals, where they are beaten, sleep deprived, electrocuted, and injected with tranquilizers or anti-psychotic drugs. Others are being taken to hospitals (also known as ankang facilities ) because their prison term or re-education term has expired and they have not yet been successfully “re-educated” in the brainwashing sessions. Others were told that they were admitted because they had a "political problem"; that is, because they appealed to the government to lift the illegal ban on Falun Gong.

Robin Munro, the former director of the Hong Kong bureau for human rights monitors and now deputy director of the online magazine China Labor Bulletin , drew public attention to the abuses of forensic psychiatry , the political abuse of psychiatry in China in general, and the abuse in particular Falun Gong practitioners. In 2001, Munro stated that forensic psychiatrists in China had been active since the days of Mao Tse-tung and were involved in the systematic abuse of psychiatry for political purposes. He said that the large-scale psychiatric abuse was the most prominent aspect of the government's protracted campaign to "destroy Falun Gong," and noted an extremely significant increase in Falun Gong practitioners' admissions to mental hospitals since the persecution began the Chinese government.

Munro went on to describe detained Falun Gong practitioners being tortured and subjected to electroconvulsive therapy, painful forms of electrical acupuncture treatment, prolonged deprivation of light, food, and water, and restricted permission to use the restrooms for "confessions" or "waivers." “To force release as a condition. This is followed by fines of several thousand yuan. Lu and Galli write that the doses of the drugs are up to five or six times higher than usual and that they are administered through a nasogastric tube. This is a form of torture or punishment, and that physical torture is widespread, including tying someone up with ropes in extremely painful postures. Such treatment can lead to chemical toxicity, migraines, extreme weakness, protrusion of the tongue, stiffness, loss of consciousness, vomiting, nausea, seizures, and memory loss.

Dr. Alan Stone, professor of law and psychiatry at Harvard University, noted that a significant number of Falun Gong practitioners held in mental hospitals had been sent there from labor camps. Stone writes, "[They] were likely tortured and then dumped in psychiatric hospitals as an appropriate disposal." Stone said that Falun Gong practitioners who were sent to psychiatric hospitals were "misdiagnosed" and "poorly." treated ”but found no definitive evidence that the use of mental health facilities was part of a unified government policy. Instead, he pointed out that the patterns of institutionalization varied from province to province.

Prisons

Since 1999, several thousand Falun Gong practitioners have been sentenced to prison terms by the criminal justice system. Most of the allegations against Falun Gong practitioners are “political offenses” such as “disturbing the social order”, “leaking state secrets”, “undermining the socialist system”, or “using a heretical organization to enforce the law undermine, ”a vague provision used to persecute people who used the Internet to disseminate information about Falun Gong, for example.

According to a report by Amnesty International, the trials of Falun Gong practitioners are "extremely unfair - the trial against the accused was biased from the start and the trial was a mere formality ... None of the allegations against the accused are related to activities that would be legally considered a crime by international standards ”.

Chinese human rights lawyers who tried to defend Falun Gong clients have faced various forms of persecution themselves, including disqualification from their profession, imprisonment, and in some cases torture and disappearance.

Social discrimination

Academic restrictions

According to the World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong (WOIPFG) Falun Gong advocacy group, school exams contained anti-Falun Gong questions and wrong answers had serious consequences. WOIPFG reported that students who practiced Falun Gong were banned from schools and universities, were not allowed to take exams, and were accepted as "guilt by association," which prevented family members of well-known practitioners from taking exams. There were also anti-Falun Gong petitions.

Outside of China

The Communist Party's campaign against Falun Gong has expanded to include diaspora communities , including the use of the media, espionage and surveillance of Falun Gong practitioners, harassment and violence against practitioners, diplomatic pressure on foreign governments, and hacking of foreign websites.

In 2004, the United States House of Representatives unanimously passed a resolution condemning attacks against Falun Gong practitioners in the United States by Communist Party agents. The resolution reports that "Chinese Communist Party societies have pressured locally elected officials in the United States into withdrawing or refusing to support the spiritual group Falun Gong"; that the homes of Falun Gong speakers were broken into and individuals who peacefully protested outside of embassies and consulates were physically assaulted.

Hao Fengjun, a former 610 Office agent and defector from Tianjin, said in a public press release in Melbourne, Australia in June 2005 that his job at the 610 Office consisted of collecting and pledging intelligence reports on foreign Falun Gong populations analyze, inter alia, in the United States, Canada and Australia.

Earlier, Chen Yonglin, a diplomat at the Chinese Consulate in Melbourne, told the media that he was also a member of the 610 Office and that his job was to monitor and infiltrate Falun Gong practitioners and keep data on everyone, no matter how small To collect and pass on connection to Falun Gong. Chen testified to the US Congress: "The war on Falun Gong is one of the main tasks of the Chinese mission abroad."

Li Fengzhi, another defector from the Chinese Ministry of State Security who carried out both national and international espionage activities, claimed that the suppression and surveillance of Christian and Falun Gong practitioners in hiding was a focus of the ministry.

In April 2006, during his state visit to Washington, DC , Chinese Communist Party leader Hu Jintao tried to convince President Bush to publicly label Falun Gong as an "evil cult" that should be banned. Bush refused.

The overseas campaign against Falun Gong is described in documents released by China's Overseas Chinese Affairs Office . In a report from a meeting in 2007 with directors of that office at the national, regional and local levels, it was stated that the office "coordinates the introduction of anti-Falun Gong struggles overseas." This office exhorted Chinese citizens overseas to participate and "determined to" aggressively expand the party line, implement and carry out the Party's Guiding Principles and Politics "and to" aggressively expand "the fight against Falun Gong, ethnic separatists and Taiwanese independent activists overseas . Other party and state organizations are believed to have participated in the overseas campaign, including the Ministry of State Security , the 610 Office, and the People's Liberation Army .

International response

Falun Gong's ordeal has attracted a great deal of international attention from governments and non-governmental organizations. Human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch expressed great concern over reports of torture and ill-treatment of practitioners in China and also called on the United Nations and international governments to intervene to stop the persecution.

The U.S. Congress has passed six resolutions against the persecution - House Concurrent Resolution 217, House Concurrent Resolution 304, House Resolution 530, House Concurrent Resolution 188, House Concurrent Resolution 218, House Concurrent Resolution 605 - that put an immediate end to the campaign against Falun -Gong practitioners both in China and abroad urge. The first resolution, Concurrent Resolution 217, was passed in November 1999. House Resolution 605, passed on March 17, 2010, calls for "an immediate end to the campaign that persecutes, intimidates, imprisons and tortures Falun Gong practitioners."

In 2008, Israel passed a new transplant law that bans the sale and procurement of organs, and ends health insurance funding for Israeli citizens receiving transplants in China.

At a rally on July 12, 2012, Congresswoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen , chairwoman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, called on the Obama administration to speak to the Chinese leadership on its human rights issues, including the repression of Falun Gong practitioners. "It is important," said Ros-Lehtinen, "that friends and supporters of democracy and human rights continue to show their solidarity and support by expressing their opinion against these abuses."

In 2012 Arthur Caplan , Professor of Bioethics, mentioned

“I believe you can make the connections that ... they use and need prisoners who are relatively healthy; they need prisoners who are relatively younger. With the best will in the world, it doesn't take a great imagination to imagine that some Falun Gong [practitioners] are among those killed for their parts. ... remember that you cannot take old people as organ sources and you cannot take sick people. You, Falun Gong, are partly younger and, because of your lifestyle, healthier. I would not be surprised if they did not use some of these prisoners as organ sources. "

On December 12, 2013, the European Parliament passed a resolution condemning the harvesting of organs from Falun Gong prisoners of conscience and calling for the immediate release of all prisoners of conscience in China. In the resolution, Parliament expressed “its deep concern at the persistent and credible reports of systematic, state-approved organ harvesting from conscientious objectors in the People's Republic of China, including large-scale Falun Gong,” without the consent of those concerned - Followers who are imprisoned for their religious beliefs, as well as members of other religious and ethnic minorities. "

On June 13, 2016, the US House of Representatives unanimously passed Resolution 343 condemning the state-sanctioned organ harvesting from Falun Gong prisoners and other minorities in China and calling on the US State Department to carry out a detailed analysis of this crime and include it in the annual human rights report publish. Furthermore, entry into the USA is to be banned for Chinese who are involved in organ harvesting.

After 119 Falun Gong practitioners from Harbin and Daqing , Heilongjiang City, were abducted by Chinese police on November 9th, 2018 , the US State Department asked the Chinese Communist Party to stop the persecution of Falun Gong. A US State Department spokesman told an Epoch Times reporter on November 29, "We urge the Chinese authorities to lift the ban on Falun Gong so they can freely practice and practice their beliefs in accordance with international human rights obligations. Religious freedom is critical to a peaceful, stable, and prosperous society. ”The State Department also noted that the United States continues to urge China to promote and protect freedom of religion for all citizens, including those who are ethnic and belong to religious minorities and those who practice their beliefs outside of officially recognized institutions, including unregistered churches, temples, mosques and other places of worship.

On November 21, 2018, Bitter Winter , an online English-language magazine from CESNUR , published a document from the Liaoning Provincial Secret Police , known as the 610 Office . The leaked document from Liaoning Province calls for proactive attacks, high-pressure intimidation, and the establishment of special forces as the key to an overall increased effort to persecute Falun Gong. The document also calls for increased surveillance of Chinese social media and chat groups to control and censor their participants and prevent them from spreading messages about Falun Gong. The document also states that anyone by the 610 Office who provides information to the US-based Minghui.org, a website documenting the persecution of Falun Gong in China, should be targeted. Observers: Massimo Introvigne , editor-in-chief of Bitter Winter and founder of CESNUR, an Italian non-profit center for new religion study that advocates religious freedom , told the Chinese-language Epoch Times that one should not believe the Chinese Communist Party is persecuting some groups because they are “extremist or violent”: “This is just Chinese propaganda. ... it simply persecutes groups that are growing rapidly and seen as potentially threatening to the Communist Party's cultural hegemony. ... False reports of extremist doctrines and violence are later created to justify the persecution. "Tina Mufford, assistant director of research and policy for the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom , described the document as alarming and worrying:" It is a Signal that the international community needs to pay more attention to marginalized communities like Falun Gong. ”Mufford added,“ It is so shocking because these are people who have done nothing wrong; they have broken no laws, they have committed no crimes, and yet the Chinese authorities are targeting and arresting them. ”Rosita Šoryte, president of the Italy-based International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees (ORLIR), a research group that collaborates Employing and advocating refugees from religious persecution, wrote that "the Chinese authorities are continuing their policies of persecution, torture and extermination instead of dialogue and mutual respect and understanding."

Reaction from Falun Gong Practitioners

Falun Gong's response to the persecution in China began in July 1999 by appealing to local, provincial and central petition offices in Beijing. This was followed by larger demonstrations with hundreds of Falun Gong practitioners traveling daily to Tiananmen Square to do the Falun Gong exercises or hold banners in defense of the practice. All of these demonstrations were interrupted by the security forces, and some of the practitioners involved were arrested and detained using force. As of April 25, 2000, a total of over 30,000 practitioners were arrested in Tian'anmen Square . Seven hundred Falun Gong practitioners were arrested during a demonstration on January 1, 2001 in Tian'anmen Square. Public protests continued until 2001. Ian Johnson wrote for the Wall Street Journal : "Falun Gong has faithfully gathered, which is arguably the most lasting challenge to authority in the 50 years of communist rule."

By the end of 2001, Tiananmen Square demonstrations had decreased and the practice itself had driven deeper underground. When public protests fell out of favor, underground practitioners set up "truth-clarifying materials" that produced literature and DVDs to refute the portrayal of Falun Gong in the official media. Practitioners distributed these materials, often door to door. Falun Gong sources estimated in 2009 that more than 200,000 such sites existed across China. The production, possession, or distribution of these materials is often a reason for security agents to sentence and detain Falun Gong practitioners.

In 2002, Falun Gong activists in China tapped television stations and replaced state television programs with their own content. One of the most noticeable events happened in March 2002 when Falun Gong practitioners in Changchun intercepted eight cable TV networks in Jilin Province and televised a broadcast entitled "Self-immolation or a fabricated act?" For almost an hour. All six of the Falun Gong practitioners involved were arrested in the following months. Two were killed immediately, while the other four died by 2010 as a result of injuries sustained in custody.

Outside of China, Falun Gong practitioners set up international media organizations in order to have greater exposure to their cause and to refute the narratives of China's state media. These include the Epoch Times newspaper , New Tang Dynasty Television and the Sound of Hope radio station. According to Zhao, through the Epoch Times newspaper , Falun Gong has entered into a "de facto media alliance" with Chinese democracy movements in exile, as their articles often featured prominent Chinese critics living abroad who criticized the People's Republic of China. In 2004, The Epoch Times published a collection of nine editorials that traced a critical history of Communist Party's rule. These editorials sparked the Tuidang Movement , which encouraged Chinese citizens to renounce their membership of the Chinese Communist Party, including the retrospective resignation from the Chinese Communist Youth Association and the Young Pioneers. Tens of millions have quit the Communist Party as part of the movement, according to The Epoch Times , but these numbers have not yet been independently verified.

In 2007, Falun Gong practitioners established Shen Yun Performing Arts in the United States , a dance and music company that tours internationally. Falun Gong software developers in the United States are also responsible for creating several popular censorship evasion tools, such as Ultrasurf, that Internet users in China use to read uncensored foreign websites.

Falun Gong practitioners outside of China filed dozens of criminal charges against Jiang Zemin, Luo Gan, Bo Xilai and other Chinese officials for genocide and crimes against humanity. According to the International Advocates for Justice , Falun Gong has made the largest number of human rights lawsuits in the 21st century, and the charges are among the most serious international crimes set by international criminal law. Since 2006, 54 civil and criminal complaints have been pending in 33 countries. In many cases, the courts have refused to judge these cases on grounds of state immunity. However, at the end of 2009, separate courts in Spain and Argentina charged Jiang Zemin and Luo Gan with "crimes against humanity" and genocide and requested their arrest. The judgment is largely seen as symbolic and is unlikely to be carried out. The court in Spain also sued Bo Xilai, Jia Qinglin and Wu Guanzheng .

Falun Gong practitioners and their supporters also filed criminal charges against technology company Cisco Systems in May 2011 on the grounds that the company had helped design and implement a surveillance system for the Chinese government to suppress Falun Gong. Cisco denied having made their technology for this purpose. China analyst and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann described in an article in World Affairs that there was a joint venture between the State Security Bureau of Shandong Province and Cisco Systems , which would further develop China's search and espionage capabilities. The Chinese authorities called it the " Golden Shield Project ". Former 610 Office worker Hao Fengjun, who used the surveillance system on a daily basis, said, “Golden Shield also includes the ability to monitor online chat services and e-mail. It identifies IP addresses and all previous communications a person has. This allows conclusions to be drawn about the location of the person, because a person will normally use the computer at home or at work. ”The arrest then took place.

Falun Gong practitioners worldwide support the efforts of the Association Doctors Against Organ Harvesting (DAFOH), who work on a political and medical level against organ harvesting from living Falun Gong practitioners in the People's Republic of China and were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016. In 2013, DAFOH initiated a global petition that collected almost 1.5 million signatures, including over 300,000 from Europe. The petition was submitted to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva , calling for an immediate end to organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners in China, an investigation into the arrest of those responsible for this crime and an end to the Chinese government's persecution of Falun Gong. The petition has been carried out annually since then.

See also

Bibliography

- Amnesty International: China: The crackdown on Falun Gong and other so-called heretical organizations. Amnesty International Publications, London 2000.

- Amnesty International: Changing the soup but not the medicine: Abolishing re-education through labor in China. Amnesty International Publications, London, (PDF).

- Benjamin Penny: The Religion of Falun Gong. University of Chicago Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-226-65501-7 .

- Danny Schechter: Falun Gong's Challenge to China: Spiritual Practice Or "Evil Cult" ?. Akashic Books, New York 2000, ISBN 978-1-888451-27-6 .

- David A. Palmer: Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-231-14066-9 .