Franz Raffl

Franz Raffl (born October 10, 1775 in Prenn, municipality of Schenna in South Tyrol , † February 13, 1830 in Reichertshofen, Upper Bavaria ) was a Tyrolean farmer.

Life

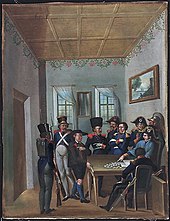

Franz grew up as the son of the sacristan Johann Raffl and his wife Maria Aigner from the district of Tall in the municipality of Schenna , formerly also Schönna, north of Meran as the seventh child of a total of 14 siblings. His father owned three eighths of the share of the local distillery. At first Raffl worked as a farmhand in the immediate vicinity of his homeland . In 1802 he married Maria Mederle, who died in 1805, whereupon he sold his farm, moved to the Passeier Valley and there on May 22, 1806 acquired the Gruebgut in Prantach. In 1807 he married Maria Molt for the second time, with whom he had seven children. On 27 January 1810 it is to the French authorities under the command of General Leonard Huard de Saint-Aubin for a reward of 1500 guilders of Tyrol as the hiding freedom fighters honored Andreas Hofer have betrayed that several uprisings against Napoleon had led troops.

In an interrogation on March 31, 1810 in Merano, Raffl himself denied responsibility for Hofer's arrest and blamed a "cure Peter". The man was later identified as the grocer Peter Ilmer, who worked as a civil cordonist at the surcharge office in St. Martin in Passeier and at the same time was employed by the French as a local overseer. In a letter to the Bavarian king from 1811, Raffl boasted that he had betrayed Hofer "exclusively and entirely". However, it is speculated that Raffl only intended with this admission to receive the reward that had not yet been paid out. In any case, eyewitnesses from 1809 still considered Raffl's entanglement to be an unproven "legend" and were not sure of his role. The assertion of the author Andreas Dipauli von Treuheim, according to which Raffl had first communicated his knowledge to the clergyman Josef Daney and who informed the French about Hofer's whereabouts, was equally dubious, which Daney vigorously denied as early as 1814. Nevertheless, the legend persisted for a long time that the illiterate Raffl was only the pastor's "tool".

Because of his alleged denunciation , as a result of which Hofer was arrested and executed , Raffl was later called the " Judas of Tyrol ". He was by no means "over-indebted", but got into financial difficulties because his creditors canceled their loans and his own father no longer wanted to be available as a surety . As a result, Raffl had to leave Tyrol and, thanks to a royal decree, was Hallknecht in Munich from 1811 until his retirement in 1820 , where he is said to have been shown around the court there "like a show animal" and introduced to the King and Crown Prince. According to the decree, for an annual wage of 250 guilders, he was responsible for "cleaning the street and the toll hall" as an unskilled worker before he was employed as a scaffold on a significantly higher income and was able to bring his family to him. A job reference from his time in Munich contradicts the prejudice often quoted in novels, legends and popular historiography , according to which he was a "unfounded, work-shy and neglected" person: "Raffl served his office with excellent loyalty with great diligence and very commendable behavior , was tolerable and calm in his behavior, but had very limited mental powers, so that despite his strong physique, he suffered an umbilical hernia while dragging the heavy weights around 1820. From 1823 Raffl received a pension, in 1830 he died in Reichertshofen near Ingolstadt He was buried two days after his death, the pastor of Reichertshofen noted in his death book some references to the importance of Raffl. 100 years later the tombstone is said to have leaned against the church wall, the grave site had already been disbanded.

reception

Raffl was increasingly demonized in the literature of the 19th century and became a clichéd traitor figure of Judas, whereby many details were embellished for lack of concrete information about his life. In retrospect, he is referred to as "red-haired", although there are no historical sources for this. Nor was he married to a "sister" of Andreas Hofer, as is sometimes claimed, in order to dramatize his story. In his story book The Wanderer (1885), Peter Rosegger circulated the fable that Raffl was buried "behind a churchyard" in the Passeier Valley in a place where no grass grew even after decades. Published in 1897 Karl Schönherr the drama The Judas of Tyrol , in 1933, directed by Franz Osten under the same title with Fritz Rasp was filmed in the lead role for the first time. 1984 appeared another film adaptation with Raffl by Christian Berger . In 2006 , Werner Asam made another film for BR under the title Der Judas von Tirol .

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Raffl, Franz . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 24th part. Imperial-Royal Court and State Printing Office, Vienna 1872, p. 227 ( digital copy ).

- Karl Schönherr : The Judas of Tyrol . Drama, 1897.

- Karl Klaar : Franz Raffl, the traitor to Andreas Hofer . Innsbruck 1921.

- H. Gritsch: Raffl Franz. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 8, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-7001-0187-2 , p. 390.

supporting documents

- ^ Andreas Oberhofer: Franz Raffl, the "Judas of Tyrol". On the construction and deconstruction of a traitor figure , in: André Krischer (Ed.): Verräter: Geschichte eines Deutungsmuster , Cologne / Weimar (Böhlau), 2019, p. 213 ff

- ^ Andreas Oberhofer: Franz Raffl, the "Judas of Tyrol". On the construction and deconstruction of a traitor figure , in: André Krischer (Ed.): Verräter: Geschichte einer Deutungsmuster , Cologne / Weimar (Böhlau), 2019, p. 217

- ↑ Ilse Wolfram: 200 years of folk hero Andreas Hofer on stage and in film , Munich 2009, p. 245

- ↑ Research and communications on the history of Tyrol and Vorarlberg , volumes 16-17 (1920), p. 189

- ↑ "Ilse Wolfram: 200 years of folk hero Andreas Hofer on stage and in film , Munich 2009, p. 245

- ^ Raffl, Franz. Accessed June 11, 2020 .

- ^ Andreas Oberhofer: Franz Raffl, the "Judas of Tyrol". On the construction and deconstruction of a traitor figure , in: André Krischer (Ed.): Verräter: Geschichte einer Deutungsmuster , Cologne / Weimar (Böhlau), 2019, p. 223 ff.

- ^ Andreas Oberhofer: Franz Raffl, the "Judas of Tyrol". On the construction and deconstruction of a traitor figure , in: André Krischer (Ed.): Verräter: Geschichte einer Deutungsmuster , Cologne / Weimar (Böhlau), 2019, p. 213 ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Raffl, Franz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Tyrolean farmer, traitor to Andreas Hofer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 10, 1775 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prenn, municipality of Schenna , South Tyrol |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 13, 1830 |

| Place of death | Reichertshofen |