Georges Bouton

Georges-Thadée Bouton (born November 22, 1847 in Paris ; † October 31, 1938 there ) was a French designer, steam car builder , automobile pioneer and member of the Legion of Honor .

family

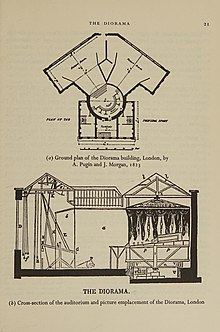

Georges Bouton was born into a family of artists in 1847. His grandfather Charles Marie Bouton was a painter and a student of Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Victor Bertin . Together with the photography pioneer Louis Daguerre, he was the inventor of the popular dioramas and later headed the company that marketed them.

His father, Georges Charles Bouton , born in Paris in 1819, was also a painter. Little is known of his work, however. From around 1840 he worked as a photographer and also worked in partnership with Daguerre.

George's father married Marie Anne Joséphine Vattebault (1825–?), A music teacher from Belleville , in 1845 . She was the daughter of the writer Augustin Vattebault . The couple had three children: Ernestine Marie (1846–?), Georges Thadée and Eugènie Ernestine (1854–1890).

youth

In 1848 the family moved to Honfleur in Normandy , where the father set up a studio on Rue Drosquet . At this time he seems to have given up painting; There are no longer any references to an activity as a painter. A little later he opened a shop in a better location, on Quai Sainte Catherine , where portraits were also photographed. Georges attended the collège on rue de l'Homme-de-Bois . In 1862 he began an apprenticeship with Dubourg Fréres in Honfleur , apparently through the mediation of the painter Louis-Alexandre Dubourg , a friend of his father's . At the blacksmith, locksmith and boat mechanic Alexandre Dubourg in the rue de la Ville , the first ship propeller was manufactured in 1832, based on an invention by Frédéric Sauvage (1785–1857).

Bouton's mother lived with the children in Honfleur until at least 1872; his father had moved to Paris in 1855. The difficult financial circumstances made it necessary to move to a more modest apartment on the Charrière Saint Léonard . Depending on the source, Marie Anne Bouton worked as a housekeeper or piano teacher.

Georges remained after his training until 1868 when Dubourg and then went to the shipyard Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée in Le Havre . According to another source, he changed the job around 1867. Employment at Mazelines in Le Havre and conscription to military service during the Franco-German War 1870–1871 followed . Little is known about this period; apparently he was assigned to the Guard Mobile and served in the Second Loire Army .

After his discharge from the military, he worked briefly with Claparèdes in Paris- Saint Denis , then with Joly in Argenteuil , with Usine Rattin in Bezons and finally as a mechanic and boiler maker with Hermann La Chapelle, Pierron & Detraitre in Saint Denis. At that time he lived on rue de Clignancourt in the 18th arrondissement . His younger sister Eugènie Ernestine soon followed to finish her teacher training in Paris and to look for a job. Contact with the father seems to have broken off during this time; however, the mother may have moved to Paris with her children.

Charles-Armand Trépardoux and the Count de Dion

The railway engineer Charles-Armand Trépardoux , with whom Bouton soon became friends, lived in the neighborhood . Trépardoux's first wife, Marie Joly, died in 1877 or 1878 . In 1879 he married Eugénie-Ernestine Bouton.

At the end of the same year, Bouton and Trépardoux went into business for themselves. They set up a simple atelier in Passage Léon , near the Rue de La Chapelle in the 18th arrondissement , in which they made physical and high-precision devices to order. In order to supplement the always tight finances, they also built detailed and very precisely manufactured steam - model ships and locomotives as well as scientific toys such as miniature steam engines , which they made on the side. These were exhibited in the Société Giroux shop (depending on the source on the Boulevard des Italiens or on the Boulevard des Capucines ), where an exclusive clientele frequented. Giroux had acquired licenses to manufacture phototechnical material from the heirs of the inventor Louis Daguerre, who died in 1851. It seems that this was how Bouton, whose grandfather had been a business partner of Daguerre, came up with a presentation opportunity for equipment and toys.

Whenever their time allowed it, but without much hope of realization, the two experimented on a lightweight, quickly heated boiler that was supposed to be suitable for installation in a vehicle. The engineer and the mechanic seem to have complemented each other well. However, the necessary financial resources were lacking for a consistent development of the project.

At the end of 1881, Bouton and Trépardoux made the acquaintance of Count Albert Jules de Dion through Giroux , who in turn was planning a steam car that was affordable for broader sections of the population. It seems that Bouton initially worked alone for the count; together, however, in the same year 1882 they set up the design office Trépardoux et Cie, ingénieurs-constructeurs , located at 22 rue Tronchet near the Porte Maillot . The choice of the name is likely due to the fact that only Trépardoux was allowed to hold the engineering title. The company's first project was the completion of Trépardoux's kettle, which was patented and made in various sizes. Even the French Navy became a customer and equipped torpedo boats and launches with boilers from De Dion, Bouton & Trépardoux .

Steam car

In 1883 a patent application was made for a steam engine to drive a four-wheeled vehicle and the first steam car was built in the same year. In 1884 two tricycles followed another four-wheeler, De Dion-Bouton La Marquise . It had a standing boiler at the front and two independently working steam engines, each with an output of 2 HP (according to the calculation method of the time), which were arranged lengthways under the footwell. The power was transmitted to each rear wheel via a long connecting rod. The rear track was significantly narrower than the front. The water supply was carried in a rectangular tank in the stern. The fuel used was kerosene, which is not explosive and therefore not very dangerous. But it can be burned so cleanly that the steam truck does not need a high chimney. Because of its participation in the race from Paris to Neuilly-sur-Seine and back in 1887, La Marquise is considered to be the first “racing car”. Registered in the light steam car class, however, the vehicle was the only one to appear at the start. With Bouton at the wheel, it covered the prescribed distance in 1 hour 14 minutes and reached 60 km / h. The average speed was 25.6 km / h. The following year the car won with an average speed of 28.9 km / h.

Steam mobiles, buses and De Dion, Bouton & Trépardoux

The following year the company was renamed Établissements De Dion, Bouton et Trépardoux and moved to rue Pergolèse 22 . De Dion was a tough businessman. As an investor, he dictated a partnership agreement that secured 80% of his income, but obliged Trépardoux and Bouton to work exclusively for the company.

Business was more than satisfactory. In 1883 a steam tricycle, mainly built by Trépardoux, appeared.

As early as 1884, the company moved into new premises in the Paris suburb of Puteaux , where it remained until production was discontinued in 1932. In 1887 it was renamed De Dion, Bouton & Trépardoux .

Internal combustion engines

Albert de Dion discovered the internal combustion engine while visiting the World Exhibition in Paris in 1889 , where the Daimler engine, later also reproduced under license by Panhard & Levassor , was presented. De Dion realized that this would be the engine of the future. Bouton was convinced early on, but the railway engineer Trépardoux remained a strict opponent of this technology, which he called "irresponsible". Nevertheless, and against the resistance of Trépardoux, the count decided to develop such engines as well and also to work on other concepts of internal combustion engines. As early as 1889, he employed the engineer Delalande independently of the company , to whom he made a specially set up studio on rue Maur available. Little is known that the count himself patented a motor around 1890 that was considered the first rotary motor . A stroke of fate struck Bouton and Trépardoux when Eugénie, Bouton's sister and Trepardoux's second wife, died shortly after giving birth in 1890.

Ultimately, however, it was Bouton, not Delalande, who made the engine functional and developed it for series production. If it is correct that, according to some sources, Bouton had been working with this engine for six years before it went into series production in 1895, then he must have been involved in the project very early on; after all, the period covers exactly the years 1889 to 1895.

When the work was moved to the plant in Puteaux in 1893 and was now under Bouton's supervision, the different opinions of the Count and Trépardoux put Bouton in a difficult position, which was increasingly exacerbated by personal tensions between de Dion and Trépardoux. But he seems to have been convinced early on that de Dion was right, on the other hand Trépardoux was his brother-in-law. Dealing with the latter must then have become more and more difficult. Nevertheless, Trépardoux finished his work on a new rear axle. In accordance with the strict terms of the contract that De Dion had dictated to his partners in return for financing the company, the latter and not Trépardoux received the patent for this axle in 1893. That is also the reason why the invention became known as the De-Dion axis .

Between Trépardoux and the quick-tempered Count de Dion, there were increasingly violent conflicts and finally a separation in anger. According to some sources, this was so severe that the count not only had Trépardoux's portrait removed from the clichés of all printing documents, but even had the old company name De Dion, Bouton & Trépardoux removed from the archive, on work pictures and on the brass plates on the machines . Immediately after Trépardoux's departure, the company was renamed De Dion-Bouton . The De-Dion-Bouton single-cylinder engine , largely designed by Bouton , became a world success; Not only did he lay the foundation for what was at times the largest automobile manufacturer in the world, a number of vehicle manufacturers also relied on this light, reliable and comparatively uncomplicated drive.

Bouton completed the first prototype of the engine in 1893. Trépardoux later married again. He looked for possible uses for his light boiler and in 1896 he filed for patents again. In 1902 he moved to Saint-Aubin-les-Forges , Département Nièvre . He died on May 4, 1920 in Arcueil-Cachan . De Dion-Bouton delivered the last steam-powered commercial vehicles in 1904.

The petrol tricycle

The first vehicle to be fitted with the new engine was the De Dion Bouton motor tricycle . The first examples appear to have gone on sale in 1895, but series production did not start until the next year. Bouton demonstrated his design on October 15, 1895 at the Tunbridge Wells Horseless Carriage Exhibition , the first such presentation in the United Kingdom . Albert de Dion also took part in this event, which was attended by many important figures for the British motor industry.

As early as May 1895, the journalist and author Louis Baudry de Saunier (1865–1938) reported on the De Dion Bouton tricycle in the magazine L'Illustration . The vehicle quickly enjoyed great popularity and was also used by women.

Inventions and patents

- Multitubular génerateur; with it he won a silver medal at the Expo 1889 and a Grand Prize with gold medal at the Exposition de la guerre 1900.

- transmission

- Fast running internal combustion engine

- Electric ignition

- Carburetor

Honors

Bouton was admitted to the Legion of Honor on March 7, 1901 for "services to the Republic".

In Narbonne , a street was named after Georges Bouton.

Appreciation

Georges Bouton was trained as a mechanic, but not an engineering degree. It is difficult to pinpoint his and Charles-Armand Trépardoux's share in the early boiler and steam car designs, and Albert de Dion also had a great technical understanding.

If the Marquis was a visionary, at least in his early years, then Bouton was the engineer who put the ideas into practice.

While Albert de Dion is described as bossy and often harsh, attributes such as friendly, courteous, serious and humble are associated with Georges Bouton. It goes with the fact that Bouton was called petit pére , little father, in a friendly and respectful manner in the company . It is not known how Bouton's relationship with brother-in-law Trépardoux later developed; the one about his noble business partner is described as characterized by great mutual respect. Both Albert de Dion and Georges Bouton fell into the same trap when, in search of a successor for the Populaire, they rejected assembly line production as qualitatively inferior for their company. As a result, this turned out to be a fatal misjudgment. While De Dion-Bouton produced rock-solid, but very conservative vehicles, these increasingly lost their competitiveness. In the 1920s, when a reorientation of the company became more and more imperative, the vehicles were less and less competitive in terms of price.

During this time, under Bouton's technical supervision, lesser-known products such as rail buses, the Train De Dion-Bouton - an intercity bus with a passenger trailer, were created.

The striking difference in size between Albert de Dion and Georges Bouton was occasionally taken up in caricatures.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Dominique Bougerie: Georges Thadée Bouton (1847–1938), p. 37 (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c d Dominique Bougerie: Georges Thadée Bouton (1847–1938), p. 38 (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c d e f Pierre Boyer, Jacques Chapuis, Alain Rambaud: De Dion-Bouton. Une aventure industrial. Edition de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN), SPADEM Adagp, 1993, ISBN 2-7118-2788-7 , p. 14.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Handwritten curriculum vitae (handwritten, 1900), p. 1 (French, accessed on November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c Dominique Bougerie: Georges Thadée Bouton (1847–1938), p. 39 (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ Information about Georges Bouton regarding the appointment as Knight of the Legion of Honor (handwritten) (French, accessed on November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c d Dominique Bougerie: Georges Thadée Bouton (1847–1938), p. 40 (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ^ A b Charles-Armand Trépardoux (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Eric Favre: De Dion-Bouton, ils ont inventé l'automobile d'aujourd'hui! From December 12, 2002 (in French, accessed November 11, 2020)

- ^ Paul Duchene: For Sale: '84 Model. Runs great. In: The New York Times, August 19, 2007. (accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b Dominique Bougerie: Georges Thadée Bouton (1847–1938), p. 41 (French, accessed on November 11, 2020)

- ^ Anthony Bird: De Dion-Bouton. First Automobile Giant. Ballantine Books, New York 1971, p. 30 (English).

- ^ A b Anthony Bird: The single-cylinder De Dion boutons. Profile Publications, Leatherhead, p. 4.

- ↑ Grace's Guide: 1895 Horseless Carriage Exhibition (accessed November 11, 2020)

- ↑ a b c d Handwritten curriculum vitae (handwritten, 1900), p. 2 (French, accessed on November 11, 2020)

- ↑ Documents on the appointment of Georges Bouton as Knight of the Legion of Honor (French, accessed November 11, 2020)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bouton, Georges |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bouton, Georges Thadée |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | French automobile manufacturer, designer and engine builder |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 22, 1847 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 31, 1938 |

| Place of death | Paris |