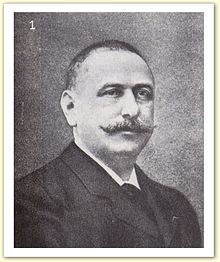

Albert de Dion

Albert Jules Graf de Dion , actually Jules-Félix Philippe Albert de Malfiance, Comte (from 1901: Marquis ) de Dion de Wandonne (born March 9, 1856 in Nantes , Loire-Atlantique department (then still Loire-Inférieure - according to other information: 1856 in Carquefou , Département Loire-Atlantique); † August 19, 1946 in the Far East ) (according to other information: in Paris ) belonged to the French high nobility . He was an automobile pioneer, a very successful entrepreneur and co-founder of what was at times the largest automobile manufacturer in the world, De Dion-Bouton . As a politician, he was a long-time member of the French National Assembly and senator for the Loire-Inférieure (now Loire-Atlantique) department.

origin

The family headquarters are in what is now the Kingdom of Belgium . It takes its name back to the Seigneurie de Dion-Le-Val fief , today a district of Chaumont-Gistoux , which an ancestor received in 1210 from Duke Heinrich I of Brabant and Lower Lorraine .

When the state of Belgium was founded in 1830, a French and a Belgian line of nobility emerged. Albert de Dion comes from the French branch of the family. Among the ancestors are a crusader , officers, politicians and higher administrative officials. The architect and architecture professor Henri de Dion (1828–1878) was also a relative; this and not Albert, who is better known to the public, is meant by the name “de Dion”, who can be found in a frieze on the Eiffel Tower with 71 other researchers and scientists .

The seat of the French de Dions until the French Revolution was the Manoir d'Hezecques in Wandonne , a hamlet near Audincthan ( Department Pas-de-Calais ) in the far north of France.

youth

Jules-Félix Philippe Albert de Dion is the son of the Marquis Louis Albert Guillaume Joseph de Dion de Wandonne (1824–1901) and of Laure Félicie Cossin de Chourses (1833–1872). In the Third Republic there were great differences in class and Albert, as a member of the French aristocracy - and of a very old family - came from an extraordinarily wealthy and privileged family. He was born with the title of Comte ( Count ) and inherited that of Marquis ( Duke ) from his father in 1901.

Albert de Dion was brought up according to his origins. At the age of 20 he was sent to Munich to study German . However, he spent a considerable amount of his time not studying, but rather building a small steam engine . He had acquired the necessary knowledge by looking and reading - secretly, because in his social environment it was almost unthinkable that he would deal with such mundane things as mechanics. His father in particular refused such employment as it was not befitting, but his mother encouraged him to do it.

Albert de Dion remained unmarried throughout his life. He was by no means a rebel and knew how to appreciate and enjoy the advantages and privileges of his noble origins. At least at a young age, social events and gambling were just as important to him and it was known that he occasionally tried to resolve differences of opinion with a duel . De Dion was a member of the socially elite Jockey Club de Paris.

De Dion-Bouton

How he came into contact with the railway engineer Charles-Armand Trépardoux (1853–1920) and his brother-in-law, the mechanic Georges Bouton (1847–1938) , is how de Dion described in his memoirs Images du Passé (1937; not available): The two ran a workshop in Paris on the Léon Passage in Clignancourt in the 18th arrondissement for the manufacture of physical and precision devices. The Count had promised, as the MC of a big ball of acting, his friend, the Duc Auguste de Morny wanted to give (1859-1920). In search of suitable cotillon articles , shortly before Christmas 1881, they visited the Giroux store on the Boulevard des Italiens, which is known for toys and such articles . A miniature steam engine built by Bouton was exhibited here. It had an alcohol burner and a glass cylinder through which the movement of the piston could be seen. It aroused de Dion's interest and made him ask for the address of the studio. An hour later, he went to Trépardoux and Bouton.

Toy making was an activity that Bouton and Trépardoux did to keep their heads above water when orders came in too sparse. Without knowing how they could finance their project for a new, very light and powerful steam boiler , they worked on its development in their free time. The area of application should be boats and a planned, own steam car . Trépardoux, a graduate of the École impériale des Arts et Métiers in Angers and a specialist in steam boiler construction and rapid evaporation, provided the basics . Already after de Dion's first visit it was agreed that the two should work for the count for 10 francs a day; with their models they came to only 8 francs a day.

With de Dion's capital, the company Trépardoux et Cie, ingénieurs-constructeurs was founded in 1882 . At 22 rue Pergolèse in the 17th arrondissement , they moved into a house with more space and a large garden, so that Trépardoux and Bouton could complete their work under better conditions. The name was chosen both because only Trépardoux had a degree in engineering, as well as to keep de Dion out of public (and paternal) perception.

The steam boiler became a great success and was available in different dimensions for different uses.

Albert de Dion discovered the internal combustion engine while visiting the World Exhibition in Paris in 1889 , where the Daimler engine, later reproduced under license by Panhard & Levassor , was presented. Not least out of consideration for Trépardoux, de Dion initially conducted research outside the company, hired the engineer Delalande, a skilled designer, and set up a workshop on rue Maur . In the search for the right concept, de Dion also developed his own ideas, which resulted in air-cooled rotary engines with 4 and 12 cylinders. He applied for a patent for a water-cooled version in 1890. It anticipated features of the well-known Gnôme aircraft engine by 15 to 20 years. The attempt to construct a two-stroke engine similar to a steam engine turned out to be a dead end. From the end of 1891 or early 1892, Georges Bouton was also involved, which led to the break with Trépardoux and his departure from the company. The De Dion-Bouton single-cylinder engine was a great success and laid the foundation for what was at times the largest automobile manufacturer in the world.

Difficult relationship with father

Albert's father, whose own hobby was archeology (he was President of the Archaeological Society of Nantes), was so critical of his entrepreneurial plans that he even tried to forbid Albert from handling these mechanical things in court, in concern for the family fortune. This preference is "childish and hardly compatible with a man of normal reason". In the course of time the relationship improved; Perhaps because of this, Albert de Dion avoided communicating his partnership in the Établissements De Dion, Bouton & Trépardoux to the outside world until 1886 . At least his father was able to experience the tremendous boom the company took.

Dreyfus affair

The artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus (1859–1935) was charged with high treason in 1894 and sentenced in a highly dubious trial. It was only years later that it became apparent that he was innocent, had intrigued government circles, army leaders and even judges in order to obtain this guilty verdict and later to thwart his rehabilitation. The Dreyfus Affair was given an additional dimension by Dreyfus' Jewish faith. It developed into one of the greatest scandals of the Third Republic and divided the nation.

De Dion was convinced of Dreyfus' guilt all his life. The affair even earned him a 15-day prison term and a fine of FF 100. On the occasion of a horse race, he hit the present President of the Republic , Émile Loubet , a Dreyfus supporter, with his walking stick on his hat without injuring him. The respected journalist and newspaper editor Pierre Giffard (1853-1922), a vehement supporter of the officer's rehabilitation, had sharply criticized this in his papers and also indicated that de Dion was abusing his political position as a deputy to favor his company. A deep enmity arose between de Dion and Giffard, and de Dion withdrew his advertisements from the Giffard newspapers Le Petit Journal and Le Vélo .

motor race

While the Count rejected car racing as such, reliability tests were a welcome opportunity for him to make the automobile itself, and De Dion-Bouton in particular, better known. He took part in several such occasions himself with his steam mobiles and supported quite a few. The Graf was the fastest in the first “official” car race in automobile history, the reliability run from Paris to Rouen on July 22, 1894. He qualified without any problems and was allowed to start the 127 km race; the trip itself came closer to a country tour with guests (among them his father as well as the Baron Étienne van Zuylen van Nyevelt and the officer and writer Émile Driant ) than a race. The victory with 3½ minutes ahead of the second (a Peugeot gasoline engine) was withdrawn from him immediately after arrival because his vehicle allegedly did not meet the requirement of "easy handling". The event was organized by the newspaper Le Petit Journal , which Pierre Giffard was behind. It is hardly surprising that de Dion therefore saw the demotion as a hostile act directed against him. Because of the well-known hostility between him and Giffard, a not inconsiderable part of the public saw it too. To this day, de Dion figures as the winner in some racing statistics.

After switching to gasoline engines, de Dion-Bouton decided not to have its own racing department, but primarily supported private drivers with logistics and know-how in the motor tricycle and voiturette classes. The De Dion-Bouton single cylinder engine was dominant in its classes and was also used successfully in licensed products and further developments. In racing, brands such as Delage , Sizaire-Naudin and initially even Renault relied on technology from Puteaux.

| date | run | brand | position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 22, 1894 | Le Petit Journal Paris-Rouen | De Dion-Bouton | 1. |

| Jun 11, 1895 - Jun 13, 1895 | Paris – Bordeaux – Paris | De Dion-Bouton | DNF |

| Sep 24 1896 - Oct 3, 1896 | Paris – Marseille – Paris | De Dion-Bouton | DNF |

| Jul 24, 1897 | Paris – Dieppe | De Dion-Bouton | 2. |

| Aug 14, 1897 | Paris – Trouville | De Dion-Bouton | 4th |

Automobile Club de France

The Count's official demotion after the Paris – Rouen race was not without consequences. So he was looking for ways to organize motorsport events in a fairer and more neutral way while at the same time promoting motorsport.

One opportunity for this was the Paris – Bordeaux – Paris race from June 11th to 13th, 1895. De Dion, like Baron de Zuylen, belonged to a committee that prepared the event, which was a kind of dress rehearsal for the founding of the Automobile Club de France ( ACF) on November 12, 1895. It was not without irony that after this race, which was subsequently run as the 1st Grand Prix of the ACF , the fastest winner was also withdrawn, although it was already evident beforehand that the vehicle was not compliant with the regulations: It had how the runner-up, only two instead of the mandatory four seats. Therefore, the third fastest was declared the winner.

De Dion was friends with van Zuylen; this also contributed substantial funds to the expansion of the De Dion-Bouton factories and the establishment of a branch in Great Britain.

The constituent meeting took place on November 12th in de Dion's house on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris, the ACF has since been considered the oldest automobile club in the world. Van Zuylen was elected the first president, an office he held until 1922; Meyan became the club's first general manager.

- In 1895 de Dion said:

- «Croyez-moi Messieurs, le monde est avec nous aujourd'hui et le mouvement à la tête duquel nous sommes sera irrésistible. Dans trois ans, nous serons deux mille membres, et il nous faudra un palais pour les recevoir ». ( Believe me, gentlemen, the world is with us today and the movement that we lead will be irresistible. In three years we will have 2000 members and it will take a palace to accommodate them. )

After a short time at a domicile at Place de l'Opéra No. 4, the club moved into a palace at Place de la Concorde No. 6-8, where it has remained to this day.

In 1898 the ACF organized the first Paris Motor Show . Here, too, Albert de Dion was a driving force.

Giffard saw in the ACF little more than an elite association and founded the Moto-Club de France as a counter-concept. This may have induced De Dion to fight Giffard directly by attacking his newspapers.

Newspaper war

De Dion used considerable funds to build a rival paper to Pierre Giffards le Vélo . He also used his relationships in industry and the nobility. Political and personal reasons for this commitment have already been given. There were also solid business interests. Le Petit Journal and Le Vélo were the most important advertising media for motor vehicles and accessories to date. Alexandre Darracq (1855–1931), whose Darracq automobiles competed by De Dion-Bouton, had invested in these newspapers and benefited accordingly. The Count succeeded in winning other business people for the project, including the tire manufacturer Édouard Michelin (1859-1940) and the car and bicycle manufacturer Adolphe Clément (1855-1928).

The new newspaper appeared under the name L'Auto-Vélo for the first time on October 16, 1900. The paper mainly reported on sports , especially motorsport , and general daily events. In its own understanding, and unlike the Giffard newspapers, it was politically neutral. Like Le Vélo , they too were geared towards high circulation. The editor-in-chief was at the suggestion of Cléments, the former cyclist and head of a cycle track , Henri Desgrange (1865-1940). Before that he was responsible for Clément's advertisements .

Even before the reliability trip from Paris to Rouen, Giffard's Le Petit Journal had designed and carried out the first “modern” cycling event in 1891 with the Paris – Brest – Paris cycling race . In particular, the networking of sport and the reporting on it was new and very successful. A second implementation did not take place until 1901. The rival newspapers organized the race together and thus reduced their own, still huge, effort. Giffard may not have been pleased, but the instruction came from the owner of the newspaper, Hippolyte Marinoni (1823–1904). L'Auto-Vélo undercut the advertising prices of the competition and successfully started organizing cycling events based on the Le Vélo model . This “poaching” went so far that the Paris – Bordeaux race was held twice in 1902: first organized by Giffard's newspaper, then by L'Auto-Vélo . The reporting developed more and more complex with telegraph stations and correspondents of international newspapers.

The idea of organizing an even bigger cycling event, the Tour de France , emerged from Desgrange's staff . It brought the newspaper an overwhelming success. In 1903 Giffard obtained a court order that the sheet had to be renamed. The new name was L'Auto . This changed nothing in the decline of the competition paper; In 1904, Le Vélo had to close. Giffard had left the year before.

L'Auto was re-established in 1946 as L'Équipe .

De Dion's detour into the newspaper industry also paid off financially.

Michel Zélélé

Zélé "Michel" Zélélé (also: "Nzelele") was supposedly the son of an Ethiopian tribal prince. In 1896 he accompanied Henri Philippe Marie d'Orléans (1867–1901), who was active as an explorer , photographer , painter and author , to France. On the recommendation of d'Orléans, Zélélé came to De Dion-Bouton and there proved to be a talented mechanic and also learned to drive. In 1900 the Count de Dion hired him as his personal driver. At the time, a black African chauffeur was so extraordinary in France that Zélélé soon became a local celebrity. De Dion-Bouton had advertising posters made, in which he sat in the driver's seat in a driver's uniform and with his arms crossed while a young lady steered her populaires with virtuosity . A picture of Zélélé at the steering wheel of a de Dion-Bouton limousine in 1906 is available from the ACF.

The always discreet Zélélé got to know many personalities from society. He stepped in to drive King Leopold II of Belgium and taught Caroline Otéro to drive.

Zélélé remained in the service of the Marquis until the death of the Marquis in 1946. He then became the driver of André Vallut , one of the designers of the Paris Métro .

politics

De Dion was active in politics from an early age; he founded the League for Universal Suffrage (for men) and served as its vice-president; a corresponding law had been in force in France since 1875.

Nationally conservative and at least a Bonapartist in the 1870s , he spoke out during the Dreyfus Affair (1895; rehabilitated 1905) as a staunch supporter of the condemnation of Dreyfus . At least during its moderate beginnings, he was close to the Ligue des Patriotes and ran as a nationalist plébiscitaire on November 5, 1899 for the parliament of the canton of Carquefou , into which he was re-elected without interruption until 1934.

National politics

After his father's death in 1901, the rank and title of marquis passed to Albert de Dion. For 22 years, from 1902 to 1924, he was a member of the French National Assembly as a member of the Loire-Inférieure (now Loire-Atlantique ) department .

| Term of office | department | Single seat for |

|---|---|---|

| Apr 27, 1902-31. May. 1906 | Loire Inférieure | without entry |

| May 6th. 1906-31. May. 1910 | Loire Inférieure | Republican nationalists |

| Apr. 24, 1910-31. May. 1914 | Loire Inférieure | Non-party |

| Apr. 26, 1914-7. Dec. 1919 | Loire Inférieure | without entry |

| Nov 16, 1919-31. May. 1924 | Loire Inférieure | Non-party |

The Marquis and the Vichy regime

This was followed by another 17 years as a member of the Senate (1924–1941). In public the Marquis was known for pointed statements and some daring statements or predictions.

When the National Assembly wanted to give the right-wing national Marshal Pétain almost absolute powers after the armistice , the conservative and Bonapartist de Dion was one of his fiercest opponents, but abstained from the vote on July 10, 1940. The marshal won by 569 votes to 80, with a large number of abstentions.

In 1944, the aged Marquis was persuaded to pose for a newspaper with Zélélé in front of a 1903 populaire . A mild form of protest against gasoline rationing has also been handed down; it is also a typical gesture for him. He had a coal-fired steam tricycle from the late 1890s set up and his no less aged chauffeur Zélélé demonstratively drive himself through the streets of Paris. He saved the coal from his allocation. There was no real need for this venture; he was evidently interested in annoying the German occupying power, which probably had no consequences for him.

Appreciation

Unlike other pioneers such as Trépardoux, Léon Serpollet , Émile Levassor , Armand Peugeot , the Renault brothers Marcel and Louis or Adolphe Clément, Albert de Dion was an amateur who had neither technical nor entrepreneurial training. Nevertheless, he had a great understanding of technical issues; In 1889 he built what was probably the first rotary engine , for which he received a patent.

At De Dion-Bouton, he made the decisions because he contributed the capital. He was a tough businessman and used his financial resources to secure complete control of the company; He treated his partners correctly but more like employees; the partnership agreements left no doubt as to where the financial resources came from. Nevertheless, Georges Bouton had his lifelong respect.

Undoubtedly, Albert de Dion was a visionary in his early years, one of whose credit it is to recognize the great ability and talent of Bouton and Trépardoux. It was his capital that brought their steam boiler to series production and thus laid the foundation for the success of what was at times the world's largest automobile and engine manufacturer, and it was his decisions that made the company one of the leaders in the industry. Particularly noteworthy are the early switch to combustion engines, the tricycle and the Voiturettes Vis-à-vis and Populaire . Then another milestone was achieved with the first V8 engine in a production car. On the other hand, he was unable to find a permanently successful follow-up project to the Voiturettes, for which the company is best known to this day. In addition, he is mainly to blame for the fact that the switch to modern production methods did not take place, which ultimately robbed De Dion-Bouton of its competitiveness. Like Bouton, he could not be dissuaded from the fact that “mass-produced goods” must necessarily be of inferior quality.

He was very careful that no one infringed de Dion-Bouton's patents and was quick to take action if he did not; conversely, he also respected the rights of other manufacturers. This led to the fact that he still referred to his populaire in advertising as petite voiture , even after the term voiturette had long since become common property because the term was protected as a model name by Léon Bollée, which de Dion readily respected.

Politically, the Count was always controversial, headstrong and by no means always acted prudently. His enmity with Pierre Giffard led to the fact that he scattered a humorous book he had written in 1899 about the emerging bicycles and automobiles ( La Fin du cheval with illustrations by Albert Robida) as his political program and made him so ridiculous.

Abert de Dion is described as class-conscious, gruff and quick-tempered. His dealings with Trépardoux after the separation or with Pierre Giffard makes it seem obvious that he could be very resentful and occasionally inclined to petty reactions.

The Dion Islands in Antarctica bear his name in his honor.

Remarks

- ↑ The anecdote was also passed down by Pierre Souvestre and Louis Lockert. both good acquaintances of the count. See Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 12. According to Evans: Steam Cars de Dion bought the miniature machine.

- ↑ Bird also mentions this incident in his 1971 trademark book.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d assemblee-nationale.fr: biography

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 159.

- ↑ a b c d e f g assemblee-nationale.fr: Mandates à l'Assemblée nationale or à la Chambre des députés

- ↑ automag.be: De Dion Genealogy

- ↑ a b c geneanet.org/: Family tree de Dion and Wandonne

- ^ A b Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 10.

- ↑ Artcurial Catalog 2007, p. 9 ( Memento from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d Fondation Arts et Métiers: Charles-Armand Trépardoux

- ↑ a b c d e f g gazoline.net: De Dion-Bouton

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 84.

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 29.

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, pp. 29-30.

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 30.

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Bird, Montagu of Beaulieu: Steam Cars, 1770-1970 (1971), p. 69

- ↑ vintagemotoring.blogspot.ch: De Dion-Bouton Paris-to-Madrid Racer

- ↑ teamdan.com: Grand Prix 1895

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, p. 15.

- ↑ a b automag.be: Dion de la Généalogie

- ↑ a b c d ACF online: Automobile Club de France - Histoire du cercle

- ↑ a b Dauncey: French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History (2012), p. 64.

- ↑ a b Nye: The Fast Times of Albert Champion. 2014, p. 215.

- ↑ a b Dauncey: French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History. 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Bird: De Dion-Bouton. 1971, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Zélélé at the wheel of a limousine, 1906 (photo: ACF)

- ^ Borgeson: Bugatti by Borgeson - The dynamics of mythology (1981), p. 35.

- ↑ auto-satisfaction.eu: L'Histoire du Zele Zelele, chauffeur du comte de Dion

- ↑ Roll- call voting results in the minutes on the website of the French National Assembly (PDF; 3.1 MB)

- ^ Bird, Montagu of Beaulieu: Steam Cars, 1770-1970 , 1971, p. 190

swell

- Anthony Bird: De Dion Bouton - First automobile Giant. Ballantine's Illustrated History of the Car marque book No 6. (1971) Ballantine Books, New York, ISBN 0-345-02322-6 . (English)

- Anthony Bird: The single-cylinder De Dion Boutons. (= Profile Publications No. 25). Profile Publications, Leatherhead, Surrey, England. (English)

- Richard J. Evans: Steam Cars (Shire Album). Shire Publications, 1985, ISBN 0-85263-774-8 . (English)

- Anthony Bird, Edward Douglas-Scott Montagu of Beaulieu: Steam Cars, 1770-1970. Littlehampton Book Services, 1971, ISBN 0-304-93707-X . (English)

- Floyd Clymer, Harry W. Gahagan: Floyd Clymer's Steam Car Scrapbook. Literary Licensing, LLC, 2012, ISBN 978-1-258-42699-6 . (English)

- John Headfield: American Steam-Car Pioneers: A Scrapbook. 1st edition. Newcomen Society in North, 1984, ISBN 99940-65-90-4 . (English)

- Hugh Dauncey: French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History. Liverpool University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84631-835-1 . (English)

literature

- Albert de Dion: Images du Passé. 1937, OCLC 14105209 .

- Griffith Borgeson: Bugatti by Borgeson - The dynamics of mythology. Osprey Publishing Limited, London 1981, ISBN 0-85045-414-X . (English)

- Anthony Bird: De Dion Bouton - First automobile Giant. (= Ballantine's Illustrated History of the Car marque book No 6). Ballantine Books, New York 1971. (English)

- Anthony Bird: The single-cylinder De Dion Boutons. (= Profile Publications No. 25). Profile Publications, Leatherhead, Surrey, England. (English)

- Jacques Rousseau: Guide de l'Automobile française. Éditions Solar, Paris 1988, ISBN 2-263-01105-6 . (French)

- GN Georgano (Ed.): Complete Encyclopedia of Motorcars, 1885 to the Present. 2nd Edition. Dutton Press, New York 1973, ISBN 0-525-08351-0 . (English)

- Richard J. Evans: Steam Cars (Shire Album No. 153). Shire Publications Ltd, 1985; ISBN 0-85263774-8 . (English)

- Anthony Bird, Edward Lord Montagu of Beaulieu : Steam Cars, 1770-1970. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd, 1971; ISBN 0-30493707-X . (English)

- Floyd Clymer, Harry W. Gahagan: Floyd Clymer's Steam Car Scrapbook. Literary Licensing, LLC, 2012; ISBN 1-258-42699-4 . (English)

- Lord Montague of Beaulieu: Nice old automobiles. Gondrom-Verlag, Bayreuth 1978.

- Ernest Schmid, Martin Wiesmann: Car veterans. Volume 4, Gloria-Verlag. Bergdietikon (Switzerland) 1967. Benz, Daimler (D), Peugeot, De Dion-Bouton, Popp, Fiat, Weber, Berna, Panhard & Levassor, Larroumet & Lagarde (F), Albion (Scot), Clement-Bayard, Turicum, Dufaux, Rover, Renault, Duhanot (F), Isotta Fraschini, Martini, Darracq, Le Zébre, Adler, Alfa Romeo, Delage, Itala, Dodge, Amilcar, Cadillac

- Hugh Dauncey: French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History. Liverpool University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84631-835-1 . (English)

Web links

- geneanet.org/: Family tree de Dion and Wandonne (French) (accessed May 25, 2014)

- gazoline.net: De Dion-Bouton: Il's ont inventés l'automobile d'aujourd'hui (French) (accessed April 19, 2014)

- Amicale De Dion-Bouton; Brand Club (French and English)

- Arts et Métiers Foundation: Charles-Armand Trépardoux (French) (accessed April 20, 2014)

- Dominique Bougerie: Honfleur Et les Honfleurais: Georges-Thadée Bouton ou La vie extraordinaire de l'éminence grise du Marquis de Dion Wandonne de Malfiance (French) (accessed June 11, 2014)

- forix.autosport.com/8W: The cradle of motorsport (accessed April 19, 2014)

- assemblee-nationale.fr: Mandats à l'Assemblée nationale ou à la Chambre des députés (French) (accessed July 15, 2013)

- assemblee-nationale.fr: biography (French) (accessed July 15, 2013)

- automag.be: Dion de la Généalogie (French) (accessed April 18, 2014)

- ACF online: Automobile Club de France - Histoire du cercle (French) (accessed April 18, 2014)

- auto-satisfaction.eu: L'Histoire du Zele Zelele, chauffeur du comte de Dion (French) (accessed April 18, 2014)

- autowallpaper.de; De Dion Bouton's story (accessed June 18, 2014)

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k613550j/f1.zoom (French) (accessed April 16, 2020)

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2837883/f4.item.zoom (French) (accessed April 16, 2020)

- https://sites.google.com/site/f1evolutions/1894-1902#dedion (accessed April 16, 2020)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dion, Albert de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dion de Wandonne, Jules-Félix Philippe Albert de Malfiance de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French Comte and Marquis, automobile pioneer, industrialist and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 9, 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Carquefou |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 19, 1946 |